ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Breast cancer brain metastases show increased levels of genomic aberration-based homologous recombination deficiency scores relative to their corresponding primary tumors

M. Diossy1, L. Reiniger2,3, Z. Sztupinszki1,4, M. Krzystanek1, K. M. Timms5, C. Neff5, C. Solimeno5, D. Pruss5, A. C. Eklund1, E. To´th6, O. Kiss6, O. Rusz7, G. Cserni7,8, T. Zombori7, B. Sze´kely9,10, J. Tı´ma´r9, I. Csabai11&

Z. Szallasi1,3,12*

1Department of Bio and Health Informatics, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark;21st Department of Pathology and Experimental Research, Semmelweis University, Budapest;32nd Department of Pathology, MTA-SE NAP, Brain Metastasis Research Group, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Semmelweis University, Budapest;42nd Department of Pediatrics, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary;5Myriad Genetics Inc, Salt Lake City, USA;6Department of Pathology, National Institute of Oncology, Budapest;7Department of Oncotherapy, University of Szeged, Szeged;8Department of Pathology, Ba´cs-Kiskun County Teaching Hospital, Kecskeme´t;92nd Department of Pathology, Semmelweis University, Budapest;10Department of Oncological Internal Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology “B”, National Institute of Oncology, Budapest;11Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Eo¨tvo¨s Lora´nd University, Budapest, Hungary;

12Computational Health Informatics Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

*Correspondence to: Dr Zoltan Szallasi, Computational Health Informatics Program (CHIP), Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02215, USA. Tel:þ1-617-355-2179; E-mail: Zoltan.szallasi@childrens.harvard.edu

Background: Based on its mechanism of action, PARP inhibitor therapy is expected to benefit mainly tumor cases with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD). Therefore, identification of tumor types with increased HRD is important for the optimal use of this class of therapeutic agents. HRD levels can be estimated using various mutational signatures from next generation sequencing data and we used this approach to determine whether breast cancer brain metastases show altered levels of HRD scores relative to their corresponding primary tumor.

Patients and methods:We used a previously published next generation sequencing dataset of 21 matched primary breast cancer/brain metastasis pairs to derive the various mutational signatures/HRD scores strongly associated with HRD. We also carried out the myChoice HRD analysis on an independent cohort of 17 breast cancer patients with matched primary/brain metastasis pairs.

Results:All of the mutational signatures indicative of HRD showed a significant increase in the brain metastases relative to their matched primary tumor in the previously published whole exome sequencing dataset. In the independent validation cohort, the myChoice HRD assay showed an increased level in 87.5% of the brain metastases relative to the primary tumor, with 56% of brain metastases being HRD positive according to the myChoice criteria.

Conclusions:The consistent observation that brain metastases of breast cancer tend to have higher HRD measures may raise the possibility that brain metastases may be more sensitive to PARP inhibitor treatment. This observation warrants further investigation to assess whether this increase is common to other metastatic sites as well, and whether clinical trials should adjust their strategy in the application of HRD measures for the prioritization of patients for PARP inhibitor therapy.

Key words:breast cancer, brain metastasis, cancer therapy

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

Introduction

The benefit of improved survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer is mitigated by the fact that 15%–20% of such patients will develop brain metastases [1]. In fact, probably due to longer survival, the incidence of brain metastasis, which is usu- ally associated with poor prognosis and severe neurological impairments [2], is rising in breast cancer [1]. Due to its unique location, and perhaps its distinct biology, treatment options have been limited.

Homologous recombination (HR) is an error-free mechanism of double-stranded DNA breaks repair, which is often deficient in breast and ovarian cancer, sensitizing them to PARP inhibitor therapy [3,4]. Currently three PARP inhibitors (olaparib, nira- parib and rucaparib) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of ovarian cancer, and olaparib has also been approved for the treatment of germline BRCA- mutated HER2– metastatic breast cancer.

These promising clinical results raise the question whether a similar clinical benefit can be achieved with PARP inhibitors in the case of brain metastases as well.

To achieve such therapeutic benefit at least two criteria need to be satisfied. First, crossing the blood–brain barrier, which was shown for both niraparib [5] and veliparib [6], making those po- tential candidates for the treatment of brain metastases.

Secondly, the brain metastases should present HR deficiency to be sensitive to this type of treatment.

Over the past decade, various studies have analyzed human cancer genomes for fingerprints left by homologous recombin- ation deficiency (HRD), and identified predictors to estimate a tumor’s response to HRD-specific therapy.

The three earliest predictors: HRD-loss of heterozygosity (HRD-LOH), large-scale state transitions (LST) and the number of telomeric allelic imbalances (ntAI), commonly known as the

“genomic scar scores,” are based on the investigated tumors’

copy-number profiles and each of them quantifies a different as- pect of the increased genomic instability linked to HRD [7–9].

Although all of these scars have the tendency to increase in HRD cases, as of today, none of them has an accepted threshold indi- vidually to separate HRDþfrom HRD– cases. These methods were later adapted by Myriad Genetics and they are currently part of the myChoice HRD test [10].

Next generation sequencing allowed the identification of the mutational signatures of somatic processes [11]. Analysis of the mutational spectra of nucleotide triplets in tumor specimens found that a signature characterized by a flat mutational spec- trum (Signature 3) was connected to HRD; thus, the relative con- tribution of the corresponding mutational process might be used as an estimator for the deficiency. The relative proportion of dele- tions caused by microhomology-mediated end joining can also be used as a robust estimator for HRD [12]. All these mutational signatures together with the so-called rearrangement signatures were combined into a robust logistic-regression model, called HRDetect [13].

It is important to emphasize that the phenotypes of the samples (i.e. HR-deficient or HR-proficient) on which all of these estima- tors relied on were determined from the genotypes of theBRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hence, determining the HR-status in a BRCA1/2 wild-type background remains a challenging task.

So far, it has not been determined how often breast cancer brain metastases show HR deficiency. We calculated HR defi- ciency measures in a published next generation sequencing data of primary breast cancer/brain metastasis pairs (hereinafter referred to as Brastianos et al. [14] cohort), followed by the myChoice HRD test in an independent cohort (validation cohort).

Materials and methods Brastianos et al. cohort

The whole exome sequencing (WES) data of the Brastianos et al. cohort were downloaded from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes, under accession number phs000730.v1.p1 [14]. The dataset contains bin- ary alignment files of primary tumors and their corresponding metastatic pairs for 21 breast cancer cases with all primary tumors having at least one matched intracranial metastasis. This breast cancer cohort formed the basis of our initial investigations.

Independent validation cohort

We collected FFPE tissues from 17 cases with primary breast cancer and corresponding brain metastases. Permissions to use the archived tissue have been obtained from the Regional Ethical Committee (No.: 510/

2013, 86/2015) and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Germline and somatic mutation calling

The samples (Brastianos et al.) were preprocessed, aligned to the hg19 reference genome with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner mem algorithm, and postprocessed (base-recalibration) by the original authors [14]. We called somatic substitutions along with short insertions and deletions with MuTect2, and germline mutations of theBRCA1andBRCA2genes with HaplotypeCaller. Both tools constitute a part of the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK 3.7) [15]. The majority of the samples were derived from formalin fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) specimens, which are well known to contain mutational biases (mostly C>T/G>A transitions) [16]. We used an approach analogous to the OxoG filter [17]

to remove mutations that were consistent with this FFPE-bias (supple- mentary Figures S1–S4andTables S5–S7, available atAnnals of Oncology online).

Genotypic background. As it was reported earlier [14], none of the Brastianos et al. samples had somatic mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2; however, four blood-derived normal samples showed deleteri- ous germline mutations being present in at least one of the genes (supple- mentary Figure S7andTable S8, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline).

Classification of deletions

Deletions were grouped into three classes (supplementary Figure S5and S6, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline): (i) if the entire deleted se- quence of a single event was repeated after the breakpoint, it was consid- ered a repeat, (ii) if only the firstnnucleotides were repeated after the breakpoint, it was considered a sizenmicrohomology and (iii) if it had no such characteristics, it was treated as a unique deletion. In order to eliminate those microhomologies that have appeared by pure chance in- stead as the result of the activity of the microhomology-mediated end joining DNA-repair pathway, they had been further divided inton<3 andn3 subgroups. In our prediction models only then3 subgroup was considered.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

Copy number analysis and genomic scar scores

Deriving copy number data from the Brastianos et al. whole exome sequences was executed using the sequenza R package [18]. The ranges of ploidy and cellularity were confined into the [1, 5] and [0.1, 1] intervals, respectively, and segmentation data were generated for autosomes only.

The three genomic scar scores were calculated using their standard defini- tions (supplementary Figures S9–S12andTable S1, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline).

The WES-HRDetect model

The original HRDetect model [13] was trained on mutational features derived from 560 breast cancer whole genome sequences, and although the authors have created an artificial whole exome variant (limiting WGS to typical WES genomic coverage area), the exact details of this computa- tional pipeline were not published. Therefore, in order to use this predict- or for our WES samples, we had to retrain the LASSO logistic regression model on the 560 artificial WES dataset, with the HRD-LOH scar scores included [13] (supplementary Figures S18–S21andTables S4 and S11, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline).

myChoice HRD analysis

DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue sections and analysis carried out as previously described by Myriad Genetics [10]. Briefly, genome-wide SNP data and sequence spanning the coding regions of 111 genes were gener- ated using a custom hybridization panel [10]. Allelic imbalance profiles were generated to determine the scores for the three genomic scars (ntAI, HRD-LOH and LST). The combined HRD score was derived from these three independent genomic scars. A myChoice HRD threshold of 42 has previously been developed to identify HR-deficient tumors using this test [10]. Tumors are considered HRDþif they have a high myChoice HRD score (42) or a tumor BRCA1/2 mutation and HRD– if they have a low myChoice HRD score (<42) and wild-type BRCA1/2.

Results

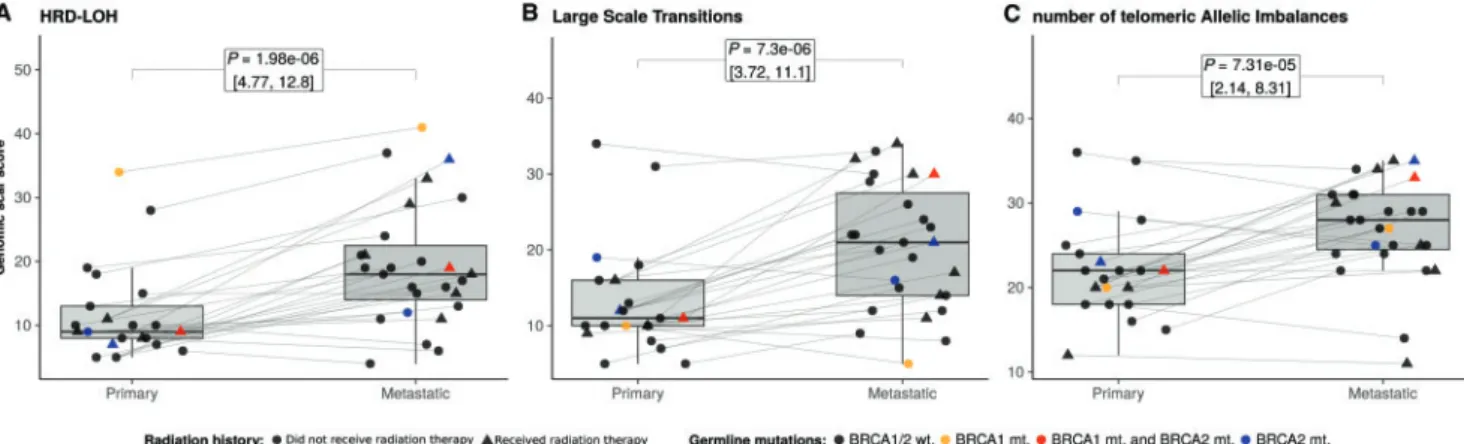

Genomic scars–based HRD measures

We determined the three genomic scar scores (HRD-LOH, LST and ntAI) in the Brastianos et al. dataset. All three WES-based scores, and their sum, had significantly increased in brain meta- stases (P0.01 for all the three measures and for their sum;

Figure1,supplementary Figures S13andS14andTables S9 and S10, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline), regardless of the mu- tational backgrounds of the samples. We also compared the scar scores of patients who received brain radiation treatment before the resection of their brain metastasis (5 of 21) to the scores of those patients who did not and found no significant difference between the two groups (supplementary Figures S15andS16, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline), suggesting that brain ir- radiation did not introduce bias into our analysis.

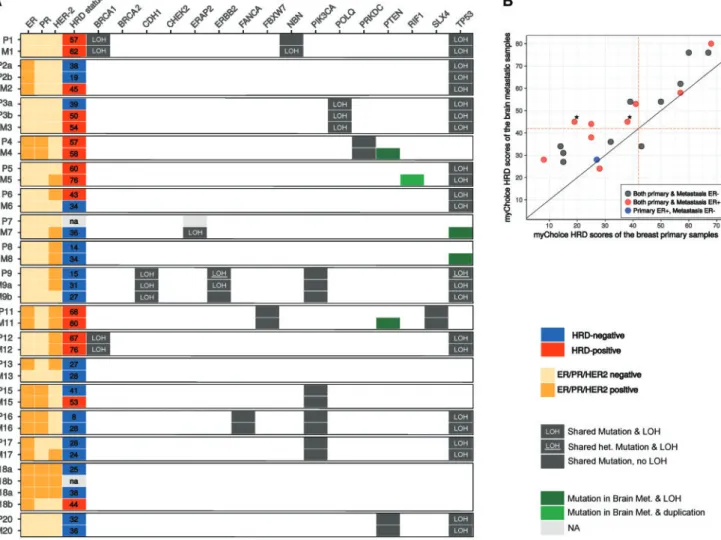

To independently validate these observations, we have assembled a cohort of primary breast cancer brain metastasis pairs, which were processed and assessed for the myChoice HRD score as described in [10]. Two of 17 of these patients (patients 1 and 12; Figure2A andsupplementary Tables S2 and S3, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline) had biallelic BRCA1 mutations (a deleterious somatic deletion and LOH in both cases), and two showed signs of monoallelic BRCA2 mutations (4 and 5); how- ever, the latter two mutations’ clinical significance could not be

determined. In one case (patient 7), the HRD score of the primary tumor could not be determined.

Figure2B shows that in 14 of 16 cases the brain metastasis had a higher myChoice HRD score than the primary tumor. In four cases, the brain metastasis “switched myChoice HRD status” rela- tive to the primary tumor from a low myChoice HRD score (HRD–) to a high myChoice HRD score (HRDþ), based on the currently accepted threshold value of 42 [10]. One of these donors’ (patient 3) metastasis, however, was likely to be derived from a HRDþrecurrent tumor that was diagnosed 4 years after the appearance of the initial tumor. The remaining three patients had estrogen receptor positive (ERþ) primary tumors and meta- stases, which means that 38% of the ERþpatients’ metastases in our validation cohort had switched HRD status. In a single case (patient 6), the metastatic sample turned out to be HRD–, while its primary counterpart was HRDþ.

As expected, the myChoice HRD scores of the two BRCA1 mutants were larger than 42, i.e. both of these samples were HRDþ. The statistical comparison of the myChoice HRD scores yielded a significant difference between the primary and meta- static groups (Figure2B), with aP-value of 5.4E–6, supporting our findings on the Brastianos et al. dataset.

We also found a significant correlation between the changes in the scar scores and the time elapsing between the detection of the primary tumor and the brain metastasis (rBrastianos¼0.52, rcontol¼0.54) in the case of both cohorts (supplementary Figures S17andS23, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline).

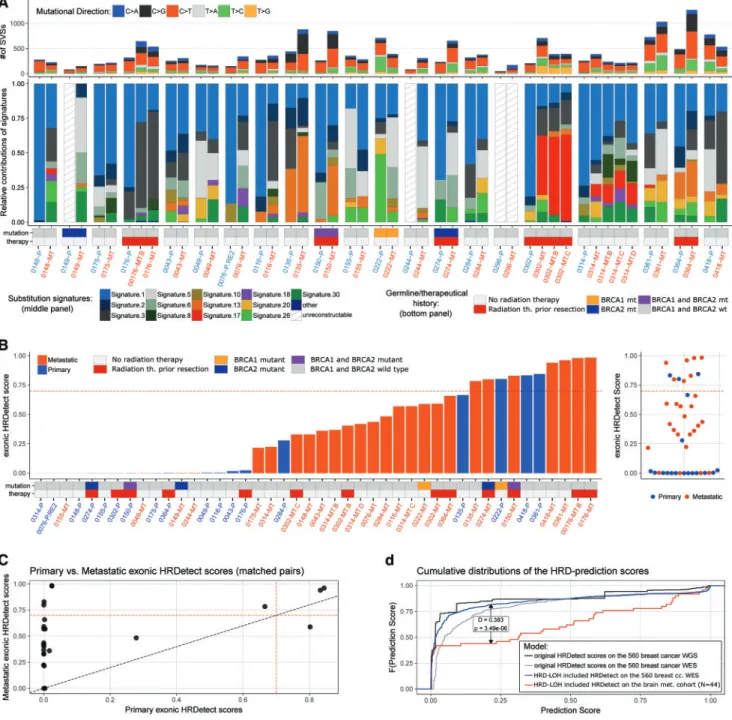

Somatic point-mutation signatures in the Brastianos et al. cohort

As a result of our signature extraction process, 3 of 21 primary samples (149, 244 and 296) and 1 of 27 metastatic samples (296) failed to pass the reconstruction step, hence their somatic signa- ture composition could not be determined (supplementary Figure S8, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline). The rest of the signature compositions are summarized in Figure3A.

We found that the primary breast tumor mutational profiles were dominated by signature 1 (aging-related signature), with lesser contributions from signature 2 (APOBEC signature), sig- nature 3 (BRCA mutation associated), signatures 5 and 6.

Strikingly, signature 3, the BRCA mutation–associated signature increased in 13 of 18 patients’ brain metastases. Interestingly, in about 20%–25% of the brain metastasis cases, signature 5 (an- other aging-related signature) has become similarly dominant as signature 1. Finally, in a single case (302), signature 17 (unknown relevance and biological origin) became the predominant muta- tional signature in the metastasis.

Analysis of deletions

Since the Brastianos dataset was whole-exome sequenced, the number of high fidelity deletions in the samples was low (7.3361.44 in primary tumors and 9.3661.49 in metastases), and although the contribution of microhomology-mediated deletions increased in the metastases (supplementary material subsection 2.3.3, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline), the dif- ference between the two groups was not significant (P¼0.13).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

WES-HRDetect scores

The original HRDetect model, developed using WGS data, is not directly applicable to WES data. Since the Brastianos et al. dataset contained only WES data, we extracted the features of HRDetect that could be calculated based on the available sequences (HRD- LOH, substitution signatures, and deletion classes) and retrained the LASSO regularized logistic regression model on them. Using the same principles as the original publication [13], we developed a similar complex measure of HR deficiency using WES data.

(For details, see supplementary materialsection 4, available at Annals of Oncologyonline.)

This WES-HRDetect model also distinguished well between HR-deficient and HR-proficient primary breast cancers, as deter- mined by e.g. BRCA mutation status (supplementary material section 4, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline). Therefore, we calculated the WES-HRDetect scores for the primary breast can- cer brain metastasis pairs as well. Compared with the results obtained by the genomic scar scores, this new measure showed an even more substantial increase of HR-deficiency in brain meta- stases relative to the primary tumors (Figure3B,C and supple- mentary Figure S22, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline). The distribution of these predictor scores was not affected by either the BRCA1/2 germline genotypes of the samples, or the brain ra- diation history of the patients.

The distribution of the breast cancer brain metastatic WES- HRDetect scores was compared with the distribution of the same model ran on the original 560 breast cancer exomes. We found a significant difference between the two cohorts (Figure3D) sug- gesting that there were significantly more tumors in the Brastianos et al. brain metastasis cohort with high (0) WES- HRDetect scores than in the pure primary cohort of breast can- cers. By using the score0.7 threshold that was determined for the original model, we concluded that four patients’ metastases changed HRD status from HRD– to HRDþ, among which two had germline mutations in at least one of theBRCA1/2 genes.

One of the BRCA1 germline patient’s (222), however, went through an opposite change; while the primary sample was HRDþ, the metastasis was HRD–.

Discussion

This work is the first demonstrating that the various DNA aberra- tion-based HRD measures are significantly higher in brain meta- stases relative to their primary breast tumor counterparts. The possibility of such an increase was previously suggested in a pub- lication showing that a BRCA1 deficient-like gene expression sig- nature is higher in breast cancer brain metastases, but that study did not use patient-matched primary metastasis sample pairs [19].

This discrepancy has several clinical consequences. Ideally, only patients sensitive to a given therapy should receive that particular treatment. In the case of PARP inhibitors, it is likely that mainly patients with HR deficiency benefit from this form of therapy.

Therefore, correlating the clinical benefit of PARP inhibitor ther- apy with HR status of the tumors has been intensely investigated [3]. However, HR status is often determined in biopsies derived from the primary tumor but clinical benefit is determined at a more advanced, often metastatic stage of the disease. If the HR de- ficiency status is significantly different in the metastases relative to the primary tumors then the observed correlations will be cor- rupted leading to contradictory clinical results. For example, in the case of breast cancer repeated observations demonstrated a correlation between the ntAI score and response to platinum- based therapy [7]. The TNT trial [20], however, studied the effi- cacy of platinum-based therapy in locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and failed to find a correlation be- tween the myChoice HRD score and response to carboplatin. It should be noted, however, that the myChoice HRD score was determined on the primary tumors and not on the metastases.

The discrepancy between the myChoice HRD score of the primary and metastatic sites presented in this study may be partially re- sponsible for this lack of correlation.

There are several ongoing clinical trials evaluating the potential clinical benefit of PARP inhibitor treatment in metastatic breast can- cer, including NCT02723864 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/

NCT02723864). This trial, however, excludes patients with active brain metastasis. Based on our results, it seems likely that breast can- cer brain metastases might be a particularly sensitive population.

Figure 1.Genomic scar scores of the Brastianos et al. breast cancer brain metastasis samples. Distributions of the homologous recombin- ation deficiency–loss of heterozygosity (HRD-LOH) (A), large-scale state transitions (LST) (B) and number of telomeric allelic imbalances (ntAI) (C) scores. The corresponding primary-metastatic pairs are connected by thin lines. Scores for each of these measures were increased in metastases compared with primary tumors withP-values of the pairedt-tests: pLOH¼1.98E–6, pLST¼7.3E–6 and pntAI¼7.31E–5, respect- ively. The brain radiation history and the germline status of theBRCA1/2genes are encoded by different shapes and colors, respectively.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

The SWOG trial S1416 is a Phase II Randomized Placebo- Controlled Trial of Cisplatin with or without ABT-888 (Veliparib) in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) and/or BRCA Mutation-Associated Breast Cancer. This trial includes patients with brain metastasis but excludes patients with estrogen receptor posi- tive breast cancer. As we showed in our validation cohort, the major- ity of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer brain metastasis cases showed high myChoice HRD scores. It might be worth establishing the proportion of HRDþERþbreast cancer cases on a larger cohort as those patients might be responding to PARP inhibitors as well.

The significant increase in HR deficiency scores in brain metasta- ses may arise due to at least two distinct mechanisms. (i) Clonal se- lection of tumor cells with higher HR deficiency score. Tumors cells with higher levels of genomic instability, higher levels of HR defi- ciency may be able to adjust more readily to a distinct environment such as the brain. (ii) It is also possible that the growing brain

metastases become gradually more genomically unstable due to some unidentified mechanism. Both mechanisms are consistent with the fact that the time elapsing between primary tumors and brain metastases often takes up to 5–10 years in breast cancer, and the length of this time showed a strong correlation with the increase in the various HRD measures in brain metastases.

Brain metastases of breast cancer patients are surgically removed with palliative intent in a significant number of cases. According to the guidelines, surgical resection is recommended in patients with a limited number (1–3) of newly diagnosed brain metastases, especial- ly with controlled systemic disease and good performance status [21]. In such cases, when the histological material is already avail- able, it might be worth considering determining the HR deficiency score in order to determine the likely sensitivity of the tumor to PARP inhibitors versus other second-/third-line therapeutic options.

Figure 2.Summary of the analysis carried out on the validation cohort by Myriad Genetics. (A) Hormone receptor and HER-2 status along with the mutational profile and HRD status of the control samples determined by Myriad Genetics. In the sample, names P stands for primary and M stands for metastasis. In the majority of cases (14 of 16), the HRD score was higher in the metastasis compared with the primary tumor. In four cases, three of which were ER positive, the HRD status of the metastasis switched to positive from an HRD negative primary.

Patients 4 and 5 had uncertainly significant BRCA2 monoallelic mutations. Mutations of eitherPTEN,RIF1orTP53were gained in five of the brain metastases. LOH was more common in the brain metastases. (B) Genomic scar scores determined by Myriad Genetics summed to- gether into a single HRD score. HRD scores were increased in metastases compared with primary tumors (P¼5.4E–6). The figure is divided into four quadrants by the HRD score¼42 lines, among which the top left quadrant contains those four cases, whose HRD status changed from HRD– to HRDþ. Two of these samples (marked with asterisks) belong to the same patient (patient 2).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

Figure 3.Somatic signature composition and WES-HRDetect scores of the Brastianos et al. samples. (A) Summary of somatic point muta- tions. The figure can be divided into three panels. The top panel contains the total number of point mutations in the samples, colored by the relative abundance of the six mutational directions. The middle panel shows the somatic point-mutation signature compositions of the triplet mutational spectra. The reconstruction errors (supplementary materialsection 3, available atAnnals of Oncologyonline) of specimens 0149-P, 0244-P, 0296-P and 0296-MT did not pass the cosine similarity threshold, hence those samples have no colors on their bars in the plot. The bottom panel of the figure indicates the germline genotype of theBRCA1/2genes in the normal sample, and the brain radiation history of the patient. (B) WES-HRDetect scores of the primary and metastatic samples. The germline genotypes of theBRCA1/2genes and brain radiation history of the patient is also presented below the bars. The red dashed line indicates the score0.7 threshold, determined by the original creators of the HRDetect model. (C) Primary WES-HRDetect scores versus metastatic WES-HRDetect scores. Noticeably, there is only a single case (PB0222) for which the primary sample’s score is significantly higher than its metastatic pairs. The difference between the two groups was tested with a paired Wilcoxon signed rank test:P¼1.64E–6. (D) Black and gray curves; cumulative distributions of the origin- al HRDetect model’s scores ran on the 560 WGS and WES. Red and blue curves: cumulative distributions of the WES-HRDetect model’s scores ran on the 560 breast cancer whole exomes and on the Brastianos et al. breast cancer dataset. The latter two distributions were compared with each other by a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, theDstatistic andP-value of which is indicated on the plot.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019

Funding

Research and Technology Innovation Fund (KTIA_NAP_13-2014- 0021 to ZS); Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF-17-156 to ZS) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation Interdisciplinary Synergy Programme Grant (NNF15OC0016584 to ZS), by the U´ NKP-17-4- III-SE-63 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities to LR and by Tesaro Inc.; The Danish Cancer Society grant (R90-A6213 to MK).

Disclosure

ZS and ACE are inventors on a patent used in the myChoice HRD assay. KMT, CN, CS and DP are employees of Myriad Genetics. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Lin NU, Bellon JR, Winer EP. CNS metastases in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(17): 3608–3617.

2. Quigley MR, Fukui O, Chew B et al. The shifting landscape of metastatic breast cancer to the CNS. Neurosurg Rev 2013; 36(3): 377–382.

3. Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;

375(22): 2154–2164.

4. Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(6): 523–533.

5. Mikule K, Wilcoxen K. Abstract B168: the PARP inhibitor, niraparib, crosses the blood brain barrier in rodents and is efficacious in a BRCA2-mutant intracranial tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14(12 Suppl 2): B168.

6. Karginova O, Siegel MB, Van Swearingen AED et al. Efficacy of carbopla- tin alone and in combination with ABT888 in intracranial murine mod- els of BRCA-mutated and BRCA-wild-type triple-negative breast cancer.

Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14(4): 920–930.

7. Birkbak NJ, Wang ZC, Kim J-Y et al. Telomeric allelic imbalance indi- cates defective DNA repair and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

Cancer Discov 2012; 2(4): 366–375.

8. Abkevich V, Timms KM, Hennessy BT et al. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epi- thelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2012; 107(10): 1776–1782.

stability consistently identify basal-like breast carcinomas with BRCA1/2 inactivation. Cancer Res 2012; 72(21): 5454–5462.

10. Telli ML, Timms KM, Reid J et al. Homologous recombination defi- ciency (HRD) score predicts response to platinum-containing neoadju- vant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(15): 3764–3773.

11. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013; 500(7463): 415–421.

12. Za´mborszky J, Szikriszt B, Gervai JZ et al. Loss of BRCA1 or BRCA2 markedly increases the rate of base substitution mutagenesis and has distinct effects on genomic deletions. Oncogene 2017; 36(35):

5085–5086.

13. Davies H, Glodzik D, Morganella S et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med 2017; 23(4): 517–525.

14. Brastianos PK, Carter SL, Santagata S et al. Genomic characterization of brain metastases reveals branched evolution and potential therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov 2015; 5(11): 1164–1177.

15. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010; 20(9): 1297–1303.

16. Oh E, Choi Y-L, Kwon MJ et al. Comparison of accuracy of whole- exome sequencing with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and fresh fro- zen tissue samples. PLoS One 2015; 10(12): e0144162.

17. Costello M, Pugh TJ, Fennell TJ et al. Discovery and characterization of artifactual mutations in deep coverage targeted capture sequencing data due to oxidative DNA damage during sample preparation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41(6): e67.

18. Favero F, Joshi T, Marquard AM et al. Sequenza: allele-specific copy number and mutation profiles from tumor sequencing data. Ann Oncol 2015; 26(1): 64–70.

19. McMullin RP, Wittner BS, Yang C et al. A BRCA1 deficient-like signa- ture is enriched in breast cancer brain metastases and predicts DNA damage-induced poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor sensitivity.

Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16(2): R25.

20. Tutt A, Tovey H, Cheang MCU et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: the TNT Trial.

Nat Med 2018; 24(5): 628–637.

21. Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, Baumert B et al. Diagnosis and treatment of brain metastases from solid tumors: guidelines from the European Association of Neuro-Oncology (EANO). Neuro Oncol 2017; 19(2):

162–174.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/9/1948/5039891 by Hungary EISZ Consortium user on 16 January 2019