Sleep in the dog: comparative, behavioral and translational relevance

Ro´bert Bo´dizs

1,2, Anna Kis

3, Ma´rta Ga´csi

4,5and Jo´zsef Topa´l

3Thedog(Canisfamiliaris)isapromisingnon-invasive translationalmodelofhumancognitiveneuroscienceincluding sleepresearch.Studiesontherelationshipbetweensleepand cognitionindogsandothercaninesareonlyjustemerging,but stillveryscarce.Hereweprovideinsightintocaninesleepand sleep-relatedphysiologicalandcognitive/behavioral

phenomena.Weshowthatdogsdonotonlyfulfilallbehavioral andpolygraphiccriteriaofsleep,butarecharacterizedby sleephomeostasis,diurnalpatternofactivity,circadian rhythms,ultradiansleepcycles,socio-ecologicallyand environmentallyshapedwake-sleepstructure,sleep-related memoryimprovement,aswellasspecificsleepdisorders.

Developmentalpatternsofsleep-relatedphysiologicalindices, aswellasparalleltrendsinage-dependentchangesin cognitionandsleepwereevidencedindogs.

Addresses

1InstituteofBehaviouralSciences,SemmelweisUniversity,H-1089 Budapest,Hungary

2EpilepsyCenter,NationalInstituteofClinicalNeurosciences,H-1145 Budapest,Hungary

3InstituteofCognitiveNeuroscienceandPsychology,ResearchCentre forNaturalSciencesH-1117Budapest,Hungary

4DepartmentofEthology,InstituteofBiology,Eo¨tvo¨sLora´ndUniversity, H-1117Budapest,Hungary

5MTA-ELTEComparativeEthologyResearchGroup,H-1117Budapest, Hungary

Correspondingauthor:

Bo´dizs,Ro´bert(bodizs.robert@med.semmelweis-univ.hu)

CurrentOpinioninBehavioralSciences2020,33:25–33 ThisreviewcomesfromathemedissueonCognitionand Perception-*Sleepandcognition*

EditedbyMichaelWLCheeandPhilippePeigneux ForacompleteoverviewseetheIssueandtheEditorial Availableonline24thDecember2019

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.12.006

2352-1546/ã2019TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierLtd.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction:why isdog sleep relevantfor humans?

Behavioral sleep is common in the animal kingdom, whereaspolygraphicallydefinedsleepisbestcharacterized inmammals[1],includingthe dog (Table 1).Thedominant (and somewhat implicitly idealized) subject of sleep researchistheyoung, healthyhumanandthelaboratory

rodent(mostoftentherat).Mostofourcurrentknowledge onsleepcomesfromthesespecies(andagegroup),thus theavailableknowledgeisseriouslyrestricted.Thenon- human/non-rodentsleepstudiesaremainlyperformedon laboratorycats[2].

Inaccordancewithsharedevolutionaryhistory(domes- tication) and social environment of family dogs and humans, the dog has been successfully applied as a model speciesforcomparative investigations ofseveral human socio-cognitive skills [3]. Considering estab- lished parallels in dog and human psychopathology [4],researchofbrainmechanisms underlyingthedog’s cognitive,behavioralandsocialdysfunctions,inthelong run, hold promise for an improved understanding of human neuropsychiatric conditions, such as obsessive- compulsive disorder[5],autism[3],orsleepdisorders, like narcolepsy, sleep-disordered breathing and REM behavior disorder (Box1).

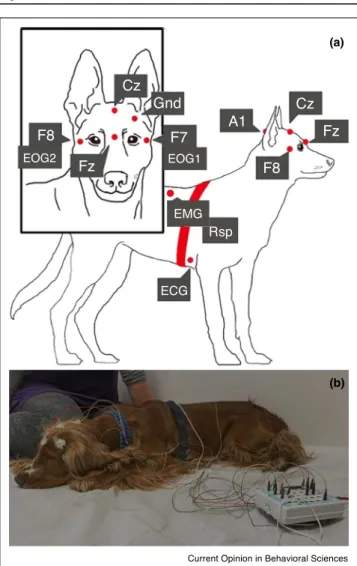

Methodologicalissuesincaninesleepstudies Sleep studies on dogs have been carried out with methods ranging from behavioral observations to sur- gical procedures, differing in invasiveness, ecological validity and specificity (Table 2). The advantages of therecentlyestablishedfamilydogsleepmodel[13] include(i)dogs’uniquewillingnesstocooperateduring the measurementstoanextentcomparabletooreven exceeding children (thus allowing the use of fully non-invasive methods), (ii) a relatively large sample size (availability of a large number of pet dogs), (iii) subjectsthatlive(andcanbemeasured)intheirnatural environment,and(iv)significantinter-breedandinter- individual variability in their human analogous social behaviorsandcognitiveperformance,includingnatural extremes (Figure 1).

Sleep-wake cyclebasics inthe domesticdog

Overallsleeplengthindogs

Comparative databases use the value of 10.1hours of averagedailysleepforthedomesticdog[14].Reported valuesvarybetween7.7and16hours[15].Whetherthe 21%/day of drowsiness seen in dogs and several other speciesbutneitherhumansnorrodents,canbeconsid- ered ‘light sleep’ [11] or a transitional state [16] is a matterofdebate,andalterstheestimationsoftotalsleep time inthisspecies [15].To putincontext, laboratory rats sleeparound 13hours,whereas humans sleep7–8 hours daily[14].

Sleephomeostasisindogs

Severalfindings indicatethe presence of sleep homeo- stasis in dogs. Lost sleep is recovered in terms of decreasedmotoractivity[17],increasedinitialslowwave sleepandalaterincreaseinthepercentageofREMsleep [18],aswellasinincreasedelectroencephalogram(EEG) slowwave/deltaactivityduring NREMsleep[19].

Growthhormonereleaseisstronglyassociatedwithearly episodesofdeep(slowwave)sleepinhumans[20],whereas

suchassociation isnotseenunderbaselineconditionsin dogs [21]. However, canine growth hormone secretion becomesassociatedwithslowwavesleepduringrebound sleep after sleep deprivation (i.e. during deeper, more intense sleep containing more slow waves) [21]. That is, the unique neuroendocrine state characterized by increasedgrowthhormoneanddecreased cortisolduring earlysleepanditsproposedrestorativeandneurocognitive functions[22]isnotemergingduringbaselineconditionsin dogs,butcanbeinducedbyincreasingsleeppressure.

Table1

Thecriteriaofsleepandtheirsfulfilmentindogsa

Specificcriteria Presenceindogs Typeofevidence (methodology)

N Reference(s) Behaviouralcriteria Motorrest ...isevidentlyassociated

withothersignsofsleep

Videorecordings, polysomnography (includingEMG)

23 [19,24]

Stereotyped posture(s)

Lyingwithheadonor betweentheforepaws,oron thesideorback,withneck musclesrelaxed

Videorecordings 24 [24]

Increased sensory thresholds

Slowwavesleep:‘Thedogs donotreactbehaviorallyto externalstimuli,butmay showashort-lasting desynchronizationofthe EEG.’

Invasive

EEGb/polysomnography

7 [16]

Reversibility- arousability

...wasprovenbyauditory stimulation

Invasive

EEG/polysomnography

5 [56]

Specificrestsites ...areusedforsleeping andarefrequentlyprovided bytheowners

Videorecordings 17 [57]

Homeostatic regulation

...wasreportedintermsof bothmotorandEEGactivity

Actigraphy,invasive EEG/polysomnography

10 [17,18]

Circadian organization

Dogsarediurnalintermsof motoractivity,corebody temperature,plasma melatoninrhythmand EEG/polygraphiccriteria

Actigraphy,metabolism kennels,repeatedblood sampling,non-invasive polysomnography

15 [17,28,58,59,25]

Eyeclosure ...ispresentinresting/

sleepingdogs

Videorecordings 24 [24]

Polygraphiccriteria (mammaliantype)

NREMc EEGslowwavesand

spindles,lackofrapideye movements;HRe<60 beats/min;slow,deep, andlessvariablebreathing;

reducedEMGf

Invasiveand non-invasive

EEG/polysomnography

14.2 [16,19,32,33,60]

REMd Lowamplitudehigh

frequencyEEGactivity (cortex),hippocampal rhythmicslowactivity,rapid eyemovements;HR<60 beats/min;rapid,shallow, andirregularbreathing;

reducedEMGwith occasionalphasicincrease (twitches)

Invasiveand non-invasive

EEG/polysomnography

aThelistoffeaturesisbasedonthecriteriasummarizedbyNicolauetal.[1].

bEEG–electroencephalography.

cNREM–nonrapideyemovementsleep.

dREM–rapideyemovementsleep.

eHR–heartrate.

fEMG–electromyography.

Circadianregulationofsleepindogs

Themajorityofmotorinactivity/polygraphicsleepofdogs occursbetween21.00and6.00withaperiodofrestduring theafternoon[17,23,24].Nightsleepwascharacterizedby higher sleep efficiency and continuity as compared to afternoonnaps[25].Corroborationofthesefindingswith thereported core bodytemperature rhythms(increasing temperatureduringmostofthelightperiodanddecreasing duringthedark)[26,27,28]clearlyindicatesadiurnaltype ofwake-sleeppatternindogs.

Ithas tobe noted however,thatunlikein humans,the circadianvariationincortisollevelisnotalwaysfoundin dogs[21,26].IncontrasttohumanmRNAlevelsofclock genesperiod1andperiod2measuredinperipheralblood mononuclearcellsreflectingevidentcircadianexpression profiles,onlyperiod1,butnotperiod2wascharacterized bysuchprofileindogs[26].Diurnalactivityofdomestic dogsishypothesizedtoreflectanadaptationtohumans, asthereisevidencefornocturnal,crepuscularorarrhyth- mic activitypatternin mostother canines, likeredand arctic foxes, as well as arctic and grey wolves, whereas diurnalactivityisarareobservation[15,29].Theweaker circadianregulation(seeforexample[30])mightresultin greater flexibility in the timing of activity in dogs as compared to humans. Thus, patterns of video-recorded sleep-wakecyclesindrugdetectordogswerenotaltered when handler-dog teams worked in different day and night shifts. The ability of dogs to cope with changing shifts may be due to their natural brief and frequent sleep-wake cycles whichmayallow themsufficientand easyadjustmenttochangingroutines,whichisusuallynot thecaseinhumans[31].

Ultradianregulationofsleepindogs

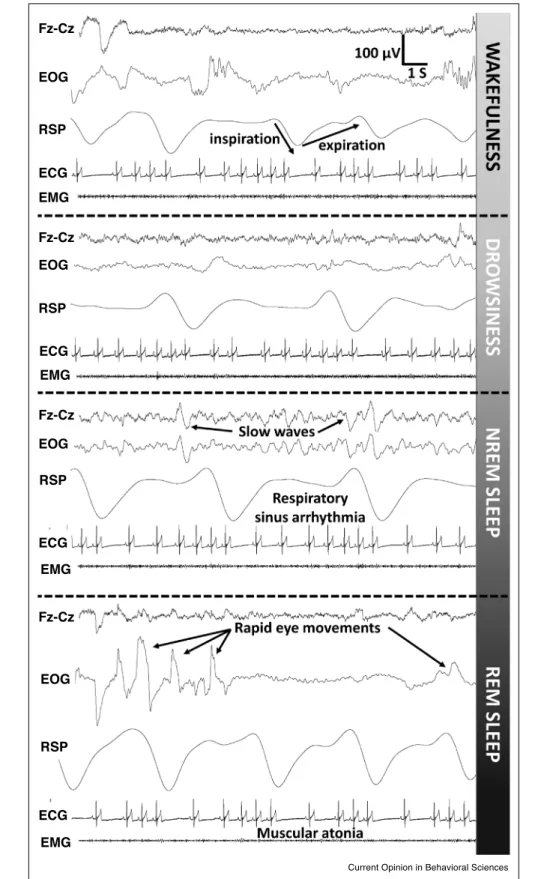

Ultradian sleep cycles of about 20-min length were described in dogs (12min of drowsiness/NREM and 6min of REM sleep episodes) with well discernible EEG,EOG (electrooculography),EMG(electromyogra- phy), ECG (electrocardiography) and respiration-related features (Figure 2; Table 3) [16,19,23,32,33].Rats and humansarecharacterizedby11and90mincycles,respec- tively.Dogsleepwasfoundtobemainlypolyphasic,with anaverageofpolyphasicwake-sleepcyclelengthof83min

Box1Sleepdisordersandbehavioralproblemsindogs Caninenarcolepsyischaracterizedbyfragmentedsleep,REM sleepdysregulation,frequentsleepattacks(excessivesleepiness) andemotion-inducedlossesinmusculartonus(cataplexy)during play,beforefeeding,andsoon.Theconditioniscausedbythe mutationofthecanineorexinreceptor2geneorbythelossof productionoftheorexinpeptides[6,7].

SleepdisorderedbreathingisassociatedwithepisodesofO2 desaturationandloudsnoringduringsleep,aswellasdaytime hypersomnolence,sluggishness,andshortenedsleeplatency.The Englishbulldog,theCavalierKingCharlesspaniel,aswellasother brachycephalicbreedsaremostcommonlyaffected.TheEnglish bulldoghasbeenproposedasanaturalmodelofsleep-disordered breathing[8,9].

REMsleepbehaviordisorderischaracterizedbyviolentmotor activityand/orcomplexbehavioralphenomenaemergingduring REMsleep.Clinicalsignsincludeepisodesofviolentlimbmove- ments,howling,barking,growling,chewing,orbiting.Episodes occurbothatnightandduringdaytimenaps[10].Behavioraloutput isclearlyunrelatedtotheactualenvironment(‘hallucinatory’).In someofthedogs,REMsleepbehaviordisorderwasassociatedwith otherneurologicalconditions,whereascongenitalformswerealso reported[11,12].

Table2

Methodologicalapproachesinstudyingdogsleep

Method Ethicalconsideration Advantage Disadvantage Reference

Invasive Cisternalpuncture/

cerebrospinalfluid extraction(associated withsleepdeprivation)

Extremelypainfuland distressing,potentiallylethal

Neurochemicalfactorscan bemeasured

Lowecologicalvalidity, restrictedsubjectpooland samplesize

[61]

Surgicallyinserted stimulation/recording electrodes

Seriouslypainfuland distressing

Highspecificity,goodsignal quality

Lowecologicalvalidity, restrictedsubjectpooland samplesize

[62,32]

Needleelectrodes introducedintotheskin andthecranialmuscles, contactingtheskull

Moderatelypainfuland distressing(semi-invasive)

Trade-offbetweensignal qualityandinvasivity

Somewhatrestrictedsubject poolandsamplesize, pharmacologicallyaltered sleep

[45]

Non-invasive Videorecordings Nodistressiscausedto subjects

Highestecologicalvalidity Lowconstructvalidity [24]

Actigraphy Notpainful,dependingon subjects’individual sensitivitymightbe moderatelydistressing

Highecologicalvalidity Lowspecificityin

differentiatingdifferentsleep states,restrictedtomotor activity

[17]

Polysomnography Notpainful,dependingon subjects’individual sensitivitymightbe moderatelydistressing

Highecologicalvalidity combinedwith electrophysiology, potentiallyhighsamplesize

Lowersignalquality, potentialneedforadaptation occasion(s)beforereaching fullecologicalvalidity

[19]

[16,23].Indogs,2.9hoursistheestimateddailyamountof REMsleep,whereas humans and rats are characterized by 1.9and 2.4hours, respectively [14]. Similar to some otherspecies like the rat, thehedgehog andthe rabbit, awakeningafteractivesleep(assumedREMsleep,based

onvideo-recordings) was found to be more common in dogs,thaninhumans,providingperhapsanopportunityto bemorealerttowardstheirsurroundingsafteraperiodof reducedresponsiveness[24].

Isthereanintraspeciesallometricscalingofsleep physiologyindogs?

Anadditionalfactortobeconsideredisthehugeindividual (between-breed)variationthatcharacterizesdogmorphol- ogy[34].Althoughtheeffectofbodysizeondogs’longevity iswell-documented[35],thehypothesisoftheintraspecies allometricscalingofphysiologicalmeasures,likeheartrate is controversial, as both confirmatory findings [36] and recentnull-resultsondatasetscontainingrest/sleepmea- surements[33,37]werereported.Althoughintriguing,the intraspeciesallometricmodulationofsleepindogswasnot yet systematically investigated, thus we do not know whethermeasuresliketotalsleeptimeorsleepcyclelength aredifferentamongbreedswithdifferentbodyweights.

Behavioraland learning-relatedaspectsof sleepin dogs

Effectsofsleeplocationandpre-sleepexperienceson sleep

Dogssleepingindoorswerereportedtospend80%ofthe nightinbehaviorallydefinedsleep,whereasthisratiowas 70%fordogssleepingoutdoorsinayard,and60%fordogs sleepingoutdoorsinanon-fencedarea[24].Apolysom- nographystudy demonstrated a later emergence of the firstREMepisodeinlaboratoryconditionsascomparedto homesleep[25].Thesefindingscoherewiththeview thatactivesleep(abehavioraldefinitionofaREMsleep- likestate)isemerginginsafesleepingconditionsmainly [24].Followingabehaviorallyactiveday,dogs,likeother mammals,includinghumanssleptmore,weremorelikely tohaveanearlierdrowsinessandNREM,andspentless timeindrowsinessand moretimein NREMandREM sleep [19,25]. In addition to physical settings and circumstances, the social context plays a decisive role in thesleep ofdogs and othercanines as well(Supple- mentary text). Pre-sleep socio-emotional experiences withnegativevalence(separationfromtheowner,threat- eningapproach byastranger)werefollowed byshorter REM sleep latency and increased REM sleep time compared to sleep following positivesocial interactions (pettingandball play).Within-subjectchangesin sleep structure were associated with behavioral reactions to pre-sleep social interactions (e.g. time spent playing or looking atthe door[38]).Pre-sleep social interaction- dependent changes in cardiac activity were not seen during sleep in dogs, whereas increased heart rate (HR) and decreased heart rate variability (HRV) after positive as compared to negative interaction could be observed during post-interventional wakefulness. This direction of change is in contrast with the expected findings and previous research on humans, perhaps

Figure1

(a)

(b) F8

EOG2 EOG1

EMG

ECG Rsp Fz

F7

A1

Cz Fz F8

Cz Gnd

Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences

Non-invasivepolysomnographyinthepetdog.(a)Placementofthe recordingelectrodesanddevicesasfollows:(i)

Electroencephalography(EEG)isperformedbyfrontalmidline(Fz), centralmidline(Cz),leftorbitofrontal(F7)andrightorbitofrontal(F8) contacts,withtheA1usedascommonreferenceandGndasground (becauseoflowerartifactcontaminationtheofflinere-referencingof Fz-Czismostfrequentlyused),(ii)Electro-oculography(EOG)is performedbythebipolarreferencebetweenF7andF8(whicharethe sameasEOG1andEOG2),(iii)Electromyography(EMG)electrodes assessingmusculartonuswerebilaterallyplacedonthemusculus iliocostalisdorsi,(iv)Electrocardiography(ECG)isassessedoverthe secondrib,(v)Respiration(Rsp)isassessedbyrespiratoryinductance plethysmographyusingarespiratorybelt.Theownerispresentand thedogispositivelyreinforcedduringtheelectrodeattachment procedure(technicaldetailsoftheattachmentareequivalenttothe onesusedinhumanstudies).(b)Aphotoofadogwithelectrodes attached.Notethecloseproximityoftheowner.(ModifiedfromRefs.

[33]and[25]).

Figure2

Fz-Cz

EOG

RSP

ECG EMG

Fz-Cz

Fz-Cz

Fz-Cz EOG

EOG

EOG RSP

RSP

RSP ECG

ECG

ECG EMG

EMG

EMG

Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences

Exemplarysegmentsofanon-invasivepolysomnographyrecordsofnighttimesleepinanadultdog.Horizontalbrokenlinesdelimitthestatesof wakefulness,drowsiness,non-rapideyemovement(NREM)sleepandRapideyemovement(REM)sleep(seenotationontheleft).Wakefulnessis characterizedbylowamplitude,highfrequencyelectroencephalogram(EEG)(frontocentralmidline,bipolarderivationFz-Cz)withoccasional(eye movement)artifacts,cleareyemovementsandblinkingasindicatedbylargedeflectionsoftheelectro-ocuologram(EOG),arespiratory(RSP)

indicatingthatincreasedactivation/emotionintensityisa keyfactor, irrespectiveofemotionalvalence [39].

Sleepandmemoryinthedomesticdog

Sleep-relatedimprovementinmemoryconsolidationof humansandrats[40]may applytodogs’inter-specific communication skills (learning new commands). A 3-hour-long post-learning non-invasive polysomnogra- phystudy[41] indicatedincreasedNREMdeltaand REMtheta,aswellasdecreasedNREMalphaactivity inpost-learningascomparedtobaselinesleepindogs.

Behavioral performance significantly increased after the 3-hour-long rest/sleep compared to the pre-sleep baseline,whereasthewithin-subjectincreaseinperfor- mancecorrelatedwithcertainaspectsofthesleepEEG spectrum(REM betaanddeltapower).Besides sleep, post learning walk and play were also associated with increasing performances approximately one week later, whereas learning of unrelated tasks had detrimental effectson memoryconsolidation[41].A behavioral study [42] somewhat contrastingly found thatplayfulactivityduringretentionenhancedmemory

(Figure2LegendContinued)frequency(frequencyrange)of15/minasindicatedbyrespiratoryinductanceplethysmographyandclear

respiratorysinusarrhythmia(theheartrateasindicatedbyelectrocardiography[ECG]increasesduringinspirationanddecreasesduringexpiration asinallfurtherpanelsandcorrespondingstates).Musculartonusisindicatedbytheamplitudeoftheelectromyogram(EMG).Drowsiness:slower theta-alphafrequencyEEGcomponents,slowereyemovements,slowregularbreathingandmaintainedmusculartonus.NREMsleep:slowEEG wavesof1 2Hzfrequency,around12/minrespiratoryfrequency,loweredheartrateanddecreasedmusculartonusareseen.REMsleep:low amplitude,highfrequencyEEG,rapideyemovements(EOG),relativelyacceleratedrespiration(15/min)andafurtherdecreaseinmusculartonus.

NotethattheverticalscalereferstotheEEGtracesonly.Therestofthederivationsareadaptedforillustrativepurposesandvisibility,buttheir scalingisconsistentacrossthepanels.Filtersettings:EEG:0.5–50Hz;EOG:0.2–10Hz;RSP:0–1Hz;ECG:0,5–50Hz;EMG:10–50Hz.

Table3

Reportedpolygraphicsignsofdifferentsleep-wakingstatesindogs

Ref. Wakefulness Drowsiness NREM REM

[32] lowamplitudeandfast frequencypatterncortical activity(desynchronization), mixtureoflowvoltageslow andfastwavesinthe hippocampaltraces

slowwavesandspindlesinthecortex,irregularslowactivityinthe hippocampus

neocortical desynchronization, 3-5Hzrhythmic hippocampalactivity

[23] low-voltage(5-10mV)fast frequency(>15Hz)EEG fromoneorbothcortical areas,frequenteye movementsandatonicbut irregularneckEMG

highvoltageslowwaves (upto40mV)EEG

12-14Hzspindlebursts (40-50mV)againsta backgroundofslower 4-8Hzactivity(10-20mV) recordedfromthe sensorimotorcortex (lightsleep);high amplitude(upto50mV) stowwaves(2-8Hz) recordedfromthevisual cortex(slowwavesleep)

relativelylow-voltage (5-10mV)fast frequency(>15Hz) tracingrecordedfrom thecorticalleads, frequentand characteristic binocular,conjugate, rapideyemovements andasuppressionof theneckEMG [16] betaactivityof<50mVin

corticalderivations(ratio alpha/betapower1),no spindles;short-lastingtheta activity(2-10s)inthe hippocampuswithhigher frequenciessuperimposed;

EMGisrelativelygreat

mixedandunstablefrequency pattern:9.5-13.5Hzwavesvary withsynchronouswavesat4–7Hz, 50-100mVonabackgroundoflow voltagefastactivity(ratioalpha/beta power>1);spindlesarelacking;

sloweyemovementsmaybe present

wavesof3-4Hzbecome predominant;spindlesof

>100mV,lasting0.2-0.5 s,mainlyinthefrontal cortex;theEMGissmall andtherearenoeye movements(lightsleep);

slowwaves(1–4Hz)of 100-250mV,

superimposedonwaves of6-7.5Hzof50-100mV;

spindlingat10–14Hz, 200mVormore;EMGis smallandthereareno eyemovements(deep slowwavesleep)

betaactivityof 50-100mV(ratio alpha/betapower

<1);hippocampal thetaactivity(5Hz);

rapideye

movements;theEMG issmall,but amplitudeincreases appear

simultaneouslywith facialorlegtwitches ormyoclonicjerks

[19] fastactivityintheEEG,high amplitudeandfrequencyeye movementsintheEOG, elevatedmuscletoneand frequentmovements (EMGchannel)

fastEEGactivityintheEEGchannel, decreasedamplitudeandfrequency eyemovements,loweredbut observablemuscletone,fairly regularrespiration

15mVdelta(1–4Hz) activity,noorlow amplitudeeye movements,regular respiration,decreased muscletone

rapideye

movements,fastEEG activity,muscular atonia,irregular respirationandheart beat

performance in theshort runtoa greaterextentcom- pared toarestingperiod.

Theeffectoflearningonsleepwasapparentwhenanalyz- ingthesamedataset[41]forsleepspindles[43].Sleep spindlesaremajorhallmarksofNREMsleepinhumans playing a definitive role in offline neuroplasticity [44].

Spindle wavesarenoteasytoassessindogs, astheyare bothshorterinduration(0.2–0.5s)ascomparedtohumans (>0.5s)andofaverylowamplitude(atleastinsurface/non- invasive traces). Sleep spindles have, however, been described in dogs using both invasive [16] and semi- invasive [45] sleep/propofol restraint EEG recordings, whereasquantitativeEEGanalysesseemtobeeffective in detectingspindle-likeactivityindogseven fromnon- invasive scalp recordings[43]. The occurrence rate of suchautomaticallymeasuredsleepspindlesinthesurface (non-invasive) EEG records was higher after learning comparedtocontroldogsandthesamemeasurecorrelated withperformanceincrease.

Developmentandaging:changesinsleepandcognition Developmental steps in the sleep EEG of dogs are characterized bygradualemergence ofsleep slow-wave activitytransientlypeakingaround6–8weeksofageand thereafter decreasing till at least 16 weeks of age [46].

SuchtransientpeakingintheamplitudeofNREMsleep slow wave activityiswellknown in prepubertalhuman subjectsandlaboratoryratsparallelingtheage-dependent trendsinsynapticdensityandbrainenergyconsumption [47].Inaddition,adult-likesleepspindlesemergearound 5weeksindogs[46]andaround12weeksinhumans[48].

Dogshavebeenshowntomanifestacognitivedeclinewith increasingage(calledtheCanineCognitiveDysfunction Syndrome; [49]),whichparallels humanageingin many aspects.Cognitivedeclineindogshasbeenassociatedwith severalbehavioralsigns,includingowner-reportedsleep- wakecyclealterations[50].Furthermore,loweramplitude ofcircadiancorebodytemperaturerhythmwasreportedin ageddogswithlowestspatialmemoryability[28].Aging was also characterized by reduced overall REM sleep amount,aswellasincreasedNREMsleepduringdaytime andwakefulnessduringnighttime[51].Thistypeofwake andsleepfragmentationduringdaytimeandnighttime, respectively, togetherwith reducedREMsleeparewell knownfeaturesofsleepintheagedhumansubjectsand wereshowntorelatewithcognitiveaspectsofaging[52,53].

Older dogs(within an agerange of 2–8 years-old)were characterized by decreased delta activity and increased alpha and beta activity both during NREM and REM, butnotduringdrowsiness[19].Inaddition,sleepspindle analysisinover150dogsindicatedthatcentrallymeasured (Cz) slow (9–13Hz) spindle density declined and fast (13–16Hz) spindle frequency increasedwith age, while on the frontal electrode (Fz), an age-related amplitude declineinslowsleepspindleswasobserved[54].There

isalsosomeindicationthatcontrarytotheage-dependent declineofrapideyemovementdensity(REMD)reported inhumans,dogs’ageispositivelyassociatedwithREMD.

Ithastobenotedhowever,thattheabovementionedeffect seems to characterize male dogswith short REM sleep duration,butnotthewholepopulation,indicatingtheneed forfurtherstudiesclarifyingitsgeneralizability[55].

Conclusion

Likemostterrestrialmammals,thedomesticdogischar- acterizedbyunequivocalsleepintermsofbehavioraland physiological criteria. The relationship between socio- ecological and physicalenvironmental, as well as cogni- tive-behavioralfactorswithsleepimprovesourinsightinto thefunctionalsignificanceofsleep,aswellasintothestill unraveledmysteriesofdogbehavior.Thisnewemerging evidencestronglysuggeststhatdogsarevalidanduseful modelsofsleep-relatedcognition.However,theachieve- ment of these goals needs further research investment, someofwhichcoulddeepenourknowledgeonbothdog andhumanbehaviorandphysiology.

Researchagenda:

Selective breeding for deeper (more intense, thus cognitivelymore efficient)sleep

Investigatingtheparallelismbetweencognitivedevel- opmentandsleepEEGmaturationindogsbymeansof non-invasivemethods

UnravellingthefunctionsofNREMandREMsleepby selective manipulations (e.g. deprivation) of these sleepstages

Integrating cognitive and affective aspects of sleep- relatedmemory consolidation

Depictingsleepelectrophysiologicalprofilesofnatural dogmodelsof humanpsychiatricconditions

Understandingtheeffectsofdomesticationonsleepby further comparisons of dogs and wolves in terms of sleepphenotypesandphysiology

Understandingtheeffectsofdifferentlifetimeexperi- ences(free-rangingdogs,petdogs,andshelterdogs)on sleepand sleep-relatedcognitiveprocesses

Conflictofinterest statement Nothingdeclared.

CRediT authorshipcontribution statement Ro´bert Bo´dizs: Conceptualization, Fundingacquisition, Visualization, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing-review&editing.AnnaKis:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing - original draft,Writing-review&editing.Ma´rtaGa´csi:Concep- tualization,Fundingacquisition,Datacuration,Writing- original draft,Writing -review & editing.Jo´zsefTopa´l:

Conceptualization, Fundingacquisition,Writing -origi- naldraft,Writing-review &editing,Supervision.

AppendixA. Supplementary data

Supplementarymaterialrelatedtothisarticlecanbefound, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

cobeha.2019.12.006.

Acknowledgements

ThewritingofthispaperwassupportedbytheHigherEducation InstitutionalExcellenceProgramoftheMinistryofHumanCapacitiesin Hungary,withintheframeworkoftheNeurologythematicprogramofthe SemmelweisUniversity;theBialFoundation(grantno169/16),the NationalResearchDevelopmentandInnovationOffice(OTKA FK128242K132372;K128448;K115862),theHungarianAcademyof Sciences(F01/031)andtheJa´nosBolyaiResearchScholarshipofthe HungarianAcademyofSciences.

References andrecommendedreading

Papersofparticularinterest,publishedwithintheperiodofreview, havebeenhighlightedas:

ofspecialinterest ofoutstandinginterest

1. NicolauMC,AkaaˆrirM,Gamundı´ A,Gonza´lezJ,RialRV:Whywe sleep:theevolutionarypathwaytothemammaliansleep.Prog Neurobiol2000,62:379-406.

2. Castro-ZaballaS,CavelliML,GonzalezJ,NardiAE,MachadoS, ScorzaC,TorteroloP:EEG40HzcoherencedecreasesinREM sleepandketaminemodelofpsychosis.FrontPsychiatry2019, 9:766http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00766.

3. Topa´lJ,Roma´nV,Turcsa´nB:Thedog(Canisfamiliaris)asa translationalmodelofautism:it’shightimewemovefrom promisetoreality.WIREsCognitSci2019,10:e1495http://dx.

doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1495.

Theoreticalandempiricalevidenceforthetranslationalrelevanceofpet dogstudiesintheresearchattemptsrevealingtheunravelthefactors involvedinautismspectrumdisorderofhumansubjectsarepresentedin thispaper.

4. OverallKL,DunhamAE:Dogsas‘natural’modelsforhuman psychiatricconditions:informationgainedfrompurely behavioralorphysiologicalstudies,versusstudiesthat combinebothapproaches.JVetBehavClinApplRes2013, 8:e43-e44.

5. LedfordH:DogDNAprobedforcluestohumanpsychiatricills.

Nature2016,529:446-447.

6. LinL,FaracoJ,LiR,KadotaniH,RogersW,LinX,QiuX,de JongPJ,NishinoS,MignotE:Thesleepdisordercanine narcolepsyiscausedbyamutationinthehypocretin(orexin) receptor2gene.Cell1999,98:365-376.

7. RipleyB,FujikiN,OkuraM,MignotE,NishinoS:Hypocretin levelsinsporadicandfamilialcasesofcaninenarcolepsy.

NeurobiolDis2001,8:525-534.

8. HendricksJC,KlineLR,KovalskiRJ,O’BrienJA,MorrisonAR, PackAI:TheEnglishbulldog:anaturalmodelofsleep- disorderedbreathing.JApplPhysiol1987,63:1344-1350.

9. HinchliffeTA,LiuNC,LadlowJ:Sleep-disorderedbreathingin theCavalierKingCharlesspaniel:acaseseries.VetSurg2019, 48:497-504.

Thestudyisabout recentcaseseriesinvestigating oneofthemost common human sleep disorders in Cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Dogbehaviorisalteredasaresultofsleep-disorderedbreathingpretty muchlikehumanbehavioris.

10. SchubertTA,ChidesterRM,ChrismanCL:Clinical characteristics,managementandlong-termoutcomeof suspectedrapideyemovementsleepbehaviourdisorderin 14dogs.JSmallAnimPract2011,52:93-100.

11. MitlerMM,DementWC:Sleepstudiesoncaninenarcolepsy:

patternandcyclecomparisonsbetweenaffectedandnormal dogs.ElectroencephalogrClinNeurophysiol1977,43:691-699.

12. BushWW,BarrCS,SteckerMM,OverallKL,BernierNM, DarrinEW,MorrisonAR:Diagnosisofrapideyemovement sleepdisorderwithelectroencephalographyandtreatment withtricyclicantidepressantsinadog.JAmAnimHospAssoc 2004,40:495-500.

13. BunfordN,AndicsA,KisA,Miklo´siA´,Ga´csiM:Canisfamiliarisas amodelfornon-invasivecomparativeneuroscience.Trends Neurosci2017,40:438-452.

Theoretically and empirically based arguments are provided for the usefulnessandrelevanceofnon-invasivedogstudiesinacomparative neuroscientificcontext.

14. SavageVM,WestGB:Aquantitative,theoreticalframeworkfor understandingmammaliansleep.ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 2007,104:1051-1056.

15. CampbellSS,ToblerI:Animalsleep:areviewofsleepduration acrossphylogeny.NeurosciBiobehavRev1984,8:269-300.

16. WauquierA,VerheyenJL,VandenBroeckWAE,JanseenPAJ:

Visualandcomputerbasedanalysisof24hsleep-waking patternsinthedog.ElectroencephalogrClinNeurophysiol1979, 46:33-48.

17. ToblerI,SiggH:Long-termmotoractivityrecordingof dogsandtheeffectofsleepdeprivation.Experientia1986, 42:987-991.

18. TakahashiY,EbiharaS,NakamuraY,TakahashiK:Temporal distributionsofdeltawavesleepandREMsleepduring recoverysleepafter12-hforcedwakefulnessindogs;

similaritytohumansleep.NeurosciLett1978,10:329-334.

19. KisA,Szakada´tS,Kova´csE,Ga´csiM,SimorP,GombosF, Topa´lJ,Miklo´siA´,Bo´dizsR:Developmentofanon-invasive polysomnographytechniquefordogs(Canisfamiliaris).

PhysiolBehav2014,130:149-156.

20. SassinJF,ParkerDC,MaceJW,GotlinRW,JohnsonLC, RossmanLG:Humangrowthhormonerelease:relationto slow-wavesleepandsleep-wakingcycles.Science1969, 165:513-515.

21. TakahashiY,EbiharaS,NakamuraY,TakahashiK:Amodelof humansleep-relatedgrowthhormonesecretionindogs:

effectsof3,6,and12hoursofforcedwakefulnessonplasma growthhormone,cortisol,andsleepstages.Endocrinology 1981,109:262-272.

22. BornJ,FehmHL:Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenalactivity duringhumansleep:acoordinatingroleforthelimbic hippocampalsystem.ExpClinEndocrinolDiabetes1998, 106:153-163.

23. LucasEA,PowellEW,MurphreeOD:Baselinesleep-wake patternsinthepointerdog.PhysiolBehav1977,19:285-291.

24. AdamsGJ,JohnsonKG:Sleep-wakecyclesandothernight- timebehavioursofthedomesticdogCanisfamiliaris.Appl AnimBehavSci1993,36:233-248.

25.

BunfordN,ReicherV,KisA,Poga´nyA´,GombosF,Bo´dizsR, Ga´csiM:Differencesinpre-sleepactivityandsleeplocation areassociatedwithvariabilityindaytime/nighttimesleep electrophysiologyinthedomesticdog.SciRep2018,8:7109.

Time-of-dayaswellasactivityandlocation-dependencyofnon-invasive polysomnographymeasuresofdog sleepare providedinthisstudy.

Findingsarerelevantfrombothasomnologicalandananimalbehavioral pointofview.

26. OhmoriK,NishikawaS,OkuK,OidaK,AmagaiY,KajiwaraN, JungK,MatsudaA,TanakaA,MatsudaH:Circadianrhythms andtheeffectofglucocorticoidsonexpressionoftheclock geneperiod1incanineperipheralbloodmononuclearcells.

VetJ2013,196:402-407.

27. GiannettoC,FazioF,PanzeraM,AlberghinaD,PiccioneG:

Comparisonofrectalandvaginaltemperaturedailyrhythmin dogs(Canisfamiliaris)underdifferentphotoperiod.Biol RhythmRes2015,46:113-119.

28. ZanghiBM,GardnerC,AraujoJ,MilgramNW:Diurnalchangesin corebodytemperature,day/nightlocomotoractivitypatterns, andactigraphy-generatedbehavioralsleepinagedcanines