Earth and Planetary Science Letters 565 (2021) 116965

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Earth and Planetary Science Letters

www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl

Zircon geochronology suggests a long-living and active magmatic system beneath the Ciomadul volcanic dome field (eastern-central Europe)

R. Lukács

a,∗, L. Caricchi

b, A.K. Schmitt

c, O. Bachmann

d, O. Karakas

d, M. Guillong

d, K. Molnár

e,f, I. Seghedi

g, Sz. Harangi

a,eaMTA-ELTEVolcanologyResearchGroup,PázmányP.sétány1/C,1117Budapest,Hungary

bDepartmentofEarthSciences,UniversityofGeneva,RuedesMaraîchers13,1205Geneva,Switzerland cInstituteofEarthSciences,HeidelbergUniversity,ImNeuenheimerFeld236,69120Heidelberg,Germany dDepartmentofEarthSciences,ETHZürich,Clausiusstrasse25,8092Zürich,Switzerland

eDepartmentofPetrologyandGeochemistry,EötvösLorándUniversity,PázmányP.sétány1/C,1117Budapest,Hungary

fIsotopeClimatologyandEnvironmentalResearchCentre,InstituteforNuclearResearch,HungarianAcademyofSciences,Bemtér18/c,4026Debrecen,Hungary gInstituteofGeodynamics,RomanianAcademy,19–21Jean-LouisCalderonSt.,R-020032Bucharest-37,Romania

a rt i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Articlehistory:

Received23April2020

Receivedinrevisedform12April2021 Accepted16April2021

Availableonlinexxxx Editor:R.Hickey-Vargas

Keywords:

zircondating magmastorage thermalmodel magmaflux crystalmush residencetime

Ciomadulis theyoungestvolcanoineastern-central Europe.Althoughitslasteruptionoccurredatca.

30ka,thereareindependentindicationsforahigh-crystallinitymagmareservoirpersistingbeneaththe volcanountilpresent.Inordertofurthertestthehypothesisoflong-livedmeltpresenceand tobetter constrainthe nature andtimescales associated withthesubvolcanic magmastoragesystem, over500 zirconU-ThandU-Pbspotages(crystalinteriorsandoutersurfaces)wereinterpretedfromdaciticrocks ofthe mostproductive eruptiveperiod(theYoungCiomadulEruptivePeriod;YCEP, 160-30ka).Zircon surfaceagesfromlavadomeand pumicesamples rangefromca. 600kauptothe youngesteruption eventat30ka.Theyformacontinuousagedistributionandsomesinglecrystalsrevealsignificantage zonation(>150kyrdifferencefromcoretorim).TheoldestzirconagesofYCEPoverlapwiththelast eruptionevents oftheOld CiomadulEruptivePeriod(1000–330ka).Thezirconagespectra,combined withtexturaldata,pointtoaprolonged(several100’skyr)residenceinahighlycrystallinemushstate.

Therangeinzirconcrystallizationtemperature(from∼750◦C tothesolidusat∼680◦C) isconsistent withtheresultsofthermometryonamphiboleandplagioclasefromfelsiccrystalclots,whichrepresent crystalmushfragments.To maintainmagmareservoirfor suchalongtime abovesolidus,continuous magmainput by deeper rechargeisrequired. Zirconcrystallization model calculations constrainedby thermal modelling imply an averagerate ofmagma input of about 1.3 × 10−4 km3/yr over 2 Myr.

Suchestimateallowsus tocalculate anextrusive/intrusiveratio of1:25–1:30.The model calculations suggest that a crystal mush zone of about 35 km3 is still present within the subvolcanic magma reservoir. Importantly, the Ciomadul plumbing system thus remains thermally primed and renewed magmainjectioncouldleadtorapidreawakeninganderuptionoftheapparentlyinactivevolcano.

©2021TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

*

Correspondingauthor.E-mailaddresses:reka.zsuzsanna.lukacs@ttk.elte.hu(R. Lukács), luca.caricchi@unige.ch(L. Caricchi),axel.schmitt@geow.uni-heidelberg.de (A.K. Schmitt),olivier.bachmann@erdw.ethz.ch(O. Bachmann),

osgekarakas@gmail.com(O. Karakas),marcel.guillong@erdw.ethz.ch(M. Guillong), molnar.kata@atomki.mta.hu(K. Molnár),seghedi@geodin.ro(I. Seghedi), szabolcs.harangi@geology.elte.hu(Sz. Harangi).

1. Introduction

Zirconprovidesvaluabletemporal,thermalandchemicalinfor- mationaboutthe stateof subvolcanicmagmastorage (seerecent reviewbyCooper,2019).Zircongeochronologycontributedsignif- icantly to the understanding of vertically extensive, trans-crustal magmaticsystemsbeneathvolcanoesthatcouldexistforduration ofseveral100’skyr(Reidetal.,1997;Wotzlawetal.,2013,Caric- chietal.,2014,2016;CooperandKent,2014;Tierneyetal.,2016;

CisnerosdeLeónandSchmitt,2019).Incombinationwiththermal modelling,zircongeochronologycanprovideessentialquantitative https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.116965

0012-821X/©2021TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

information on the thermal evolution, accumulation andvolume oferuptiblemagmainvolcanicplumbingsystems.Afundamental questionthatremainsopeniswhethermagmaticsystemscancon- tain some meltfractions forprolonged(several10’s to100’skyr) time periods (e.g., Reid and Vazquez, 2017; Szymanowski et al., 2017)orwhethertheyaremostlystoredinasubsolidusstate(e.g., Cooper andKent, 2014;Rubin et al., 2017). Geophysical dataare consistent withmodelssuggestingthat subvolcanicmagmareser- voirs are dominantly crystal-richand contain a melt fraction, on average, between ∼5 and 30% (e.g., Pritchard and Gregg, 2016).

Zircon studies show that such conditions can last for prolonged period not only in large-volume, silicic magmatic systems (e.g., Toba, Okataina, Mogollon-Datil volcanic field; Cerro Galán; Bach- mannetal.,2007;Folkesetal.,2011;Stormetal.,2011;Wotzlaw et al., 2013; Reid andVazquez, 2017; Szymanowski et al., 2017), but itseems toalso apply to andesiticand dacitic arcvolcanoes (e.g., Mt St Helens, Lassen Peak; Claiborneet al., 2010; Klemetti and Clynne, 2014). The presence of potentially eruptible melt in the magmaticreservoir could lead torapid reawakening (days to years; e.g.Burgisser andBergantz,2011;Druitt etal.,2012; Con- wayetal.,2020)andthisposesanunderratedriskparticularlyin caseoflong-dormant,apparentlyinactive,volcanoes.Thus,abetter understandingofthetemporalevolutionofthethermalconditions within theirmagmaticsystemsisessentialtoestimatethepoten- tialwhethertheycaneruptagain.

Ciomadul is the youngest volcano in eastern-central Europe, withitslast eruption occurringatca.30ka(Harangietal.,2010, 2015a, 2020; Szakács et al., 2015; Molnár et al., 2019). Yet, re- sultsofgeophysicalsurveys,conductivityexperimentsandcarbon- dioxidegas-monitoringcampaignsareinagreementwiththepres- ence of a melt-bearing magma reservoir at subvolcanic depths (Popa et al., 2012; Harangi et al., 2015b; Kis et al., 2019; Lau- monier et al., 2019). To further constrain the timescale of the magmastoragesystemandthepotentialmelt volumesinit,here wecombinenewzirconU-ThandU-Pbdatawiththosepublished for the youngest volcanic units (Harangi et al., 2015a) and the oldest domes (Lukácset al., 2018). Thisdata set now covers the entire1MyrlongeruptionhistoryofCiomadulinastatisticallyro- bustmanner. Zirconagespectraserveasan importantparameter in thermalmodelling to constrain magma fluxesand volumesof magmareservoiratagiventime(Caricchietal.,2014,2016;Tier- ney etal.,2016;Weber etal., 2020a).Inthiswork, we havefur- therrefinedzirconcrystallizationmodellingandaddedTi-in-zircon temperaturestobetterconstrainthenatureofthemagmaticstor- agesystemandapplythistechniqueforCiomadul,asmall-volume, long-dormantvolcano.Ourresultsshowthatasilicicmagmareser- voir with >100 km3 in volume, mostly in a highly crystalline state,butwithasignificantproportionofmeltcandevelopevenat such volcanoesfed atrelatively lowmagma flux(<10−3 km3/yr) overlongperiodsoftime(>1 Myr).Existenceofsizeableeruptible magmapockets (with<∼50vol%crystals) beneathlong-dormant volcanoesposesagreater potentialhazard thanpreviouslyappre- ciated.

2. Geologicalbackground

TheCiomadulvolcanicdomefield(CVDF)istheyoungestman- ifestation of the volcanism in eastern-central Europe (Fig. 1). It is locatedat thesoutheastern end ofthe 160kmlong C˘alimani- Gurghiu-Harghitavolcanic chain.Acomprehensive eruptionchro- nology wasreconstructed bycombined(U-Th)/He,U-ThandU-Pb zircon dating (Harangi et al., 2015a; Molnár et al., 2018, 2019) and was supported by new K/Ar ages (Lahitte et al., 2019). Ac- tivitystartedwithintermittentsmallvolumelavadomeextrusions withacumulative erupted magmavolumeof∼1km3 inanarea of 400km2 from1 Ma to ca.350 kawith long(>100kyr)qui-

escenceperiodsbetweeneruptions(OldCiomadulEruptivePeriod;

OCEP).Then,theeruptionsfocusedonamorerestrictedareadur- ing the Young Ciomadul Eruptive Period (YCEP) from 160 to 30 ka,which is subdividedinto two main eruptive epochs andsev- eralminoreruptiveepisodesthatoccurredat160–150ka(episode 4/1), 140–125 ka (episode 4/2), 105–95 ka (episode 4/3), 56–45 ka (episode 5/1), 35-30 ka (episode 5/2) and separated by qui- escence periods lasting for ca. 15–40 kyr. The YCEP constructed the Ciomadul volcanic complex (CVC) with ∼7 km3 cumulative eruptedmagma volume.Extrusion ofviscous magmaoccurredin distinct vents a few km apart and this lava dome complex was truncated by two deep explosion craters during the latest stage ofthevolcanism(Szakácsetal.,2015;Karátsonetal., 2016). The maximumeruptionrate(∼0.1 km3/yrlastingoverca.60kyr)was reachedduring the Eruptive Epoch4 of the YCEP(Molnár etal., 2019).

Compositionally,Ciomadulvolcanismischaracterizedbyarela- tively homogeneous, crystal-rich (30–40 vol% crystals inthe lava dome rocks and 20–25 vol% in pumices) high-K dacitic magma with dominantly plagioclase, amphibole and biotite phenocrysts (Seghedietal., 1987; Vinkleretal., 2007; Kissetal., 2014; Mol- nár et al., 2018, 2019). This differs significantly from the vol- canic products of thepre-Ciomadul volcanismin South Harghita.

The Ciomadulrocks have typically high abundanceof Ba and Sr, depletion in Y and heavy rare earth elements and no negative Eu-anomaly. Amphiboles display significant compositional varia- tionsandzoning patternssuggestinginteractions ofcomposition- ally variable magmas (Kiss et al., 2014; Laumonier et al., 2019;

Harangi et al., 2020). Hornblende along withplagioclase macro- crystscrystallizedatrelativelylowtemperatureof∼700–750◦Cin an upper crustal felsic magma reservoir, whereas pargasitic am- phiboleformedat>900◦C frommoremafic magmas(Kiss etal., 2014;Laumonieretal.,2019).Presenceofhigh-Mgmineralphases, such as olivine, orthopyroxene and clinopyroxene in the dacites indicates that mafic magma recharge likely reactivated the felsic crystalmush(Vinkleretal.,2007;Kissetal.,2014).

3. Methods

Samplesalreadyused forzircondating (Harangietal., 2015a;

Lukács et al., 2018) were completed with additional ones from lava dome rocks and pumices. Now, this sample set represents theentireeruptiveepisodesoftheYCEP.Zirconcrystalsweresep- arated from crushed and sieved (<250 μm) bulk samples using standarddensityandmagneticseparationtechniques,followedby handpickingunderabinocularmicroscope.Unpolishedzirconsur- faces(outer∼4 μmrims;depthprofilingmeasurements)andsec- tionedinteriors (mantlesand rarevisually identified coresbased on CL images) were analysed for 238U-230Th geochronology by sensitive high resolution secondary ion mass spectrometryusing a CAMECA ims 1280-HR ion microprobe at the HIP Lab of the Institute of Geosciences, Heidelberg University, Germany and a CAMECAims1270 atthe University of Los Angeles.Analysis pro- tocolsaredetailedinAppendixTable A.1.Accuracywasmonitored by interspersed analysis of AS3 and91500 zircon reference ma- terialsinboth laboratories.UCLAanalyses onstandardsyieldeda unitysecularequilibriumratiofor(230Th)/(238U)=1.022 ±0.016 (1

σ

,MSWD=0.5;n=8),whereasincaseofthesurface-analyses it was (230Th)/(238U) = 0.981 ± 0.015 (1σ

, MSWD = 2.2; n = 29).FortheHeidelberganalysissession,secularequilibriumrefer- encezirconanalysesaveraged (230Th)/(238U) =0.990±0.006 (1σ

, MSWD= 0.69, n = 33). Uraniumconcentrations wereestimated fromUO+/Zr2O+4 intensityratiosrelativetozirconreference91500 (U= 81.2ppm;Appendix Table A.1).Modelages werecalculated using the mean whole rock Th/U value of the Ciomadul dacitesR. Lukács, L. Caricchi, A.K. Schmitt et al. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 565 (2021) 116965

Fig. 1.a)Simplifiedmap(originalsource:Seghedietal.,1987)oftheCiomadulvolcanicdomefield(CVDF)anditssurroundings.Thetwincratersofepisodes5/1and5/2are outlinedbyboldblacklines.b) EruptionchronologyoftheCVDFafterMolnáretal. (2018,2019),showingtheepochs(andepisodes)oftheYoung(YCEP)andOldCiomadul EruptivePeriods(OCEP).Eruptionstyles,i.e.lavadomeextrusionvs.explosiveeruptionareindicatedabovetheeruptionagecurves(Gaussianprobability,eruptionagewith uncertainties).c) Cumulativeeruptedvolumesoftheeruptiveepochs(Szakácsetal.,2015;Karátsonetal.,2019;Molnáretal.,2019).(Forinterpretationofthecoloursin thefigure(s),thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.)

(3.58; Harangi etal., 2015a) andassuming secular equilibriumof the melt. Because the zircon-whole rock isochron slope is dom- inated by the zircon composition, variations in the melt compo- sition withinreasonablelimitswillnot significantly changethese model ages. Incase ofsome secular equilibrium zircondomains, we additionallyperformedU-Pb analyseswiththesameSIMS in- struments.ZirconU-Pbdateswere correctedforinitialdisequilib- riumof230ThusingaconstantDvalueof0.33±0.06(Rubattoand Hermann,2007;AppendixTable A.1)toobtaininternallyconsistent resultswiththosepublishedbyLukácsetal.(2018).

Zircon trace elements including Ti, Y, Hf and REE analyses wereperformedbylaserablationinductivelycoupledplasmamass spectrometry (ICP-MS) atthe Departmentof EarthSciences, ETH Zürich with a Thermo Element XR SF-ICP-MS using 30 μm spot diameter (∼10 μmdepth) on the same samplesanalysed for in- situgeochronology.Foradditionalinformationabouttraceelement measurements see Appendix Table A.2. Because of thedifference in sampling volume and the ageheterogeneity within individual crystals,wedidnotcorrelateanalysesforgeochronologyandgeo- chemistry.ThenewlyobtainedYCEPtraceelementdatawerecom- bined withthe YCEPzircon agedata fromHarangi etal.(2015a) andOCEP zirconage datafromLukácsetal.(2018). Additionally, we performed zircon trace element analyses alsoon these latter samples,usingthesamemethodasforYCEPzircons.

4. Results

Over500zircon U-Th(138 surfacesand312interiors) andU- Pb (65 interiors) spot ages from the youngest volcanic episode (YCEP)ofCiomadulwerecompiledinthisstudy.Theseinclude334 newly obtained geochronological analyses andalready published datafromsomeoftheyoungesteruptionproducts(seeHarangiet al., 2015a) andfrom oneof theoldest lava domeof YCEP(KHM, Lukács etal., 2018). The newzircon analyses partly targetedthe so farunrepresented lava domesof YCEP(epoch 4) andalso ex- tendedthedatasettoepoch5inordertogetastatisticallyrobust dataset,whichcoversmostoftheeruptedmaterialsofallthefive YCEPeruptiveepisodes(Fig.2,AppendixTable A.1).

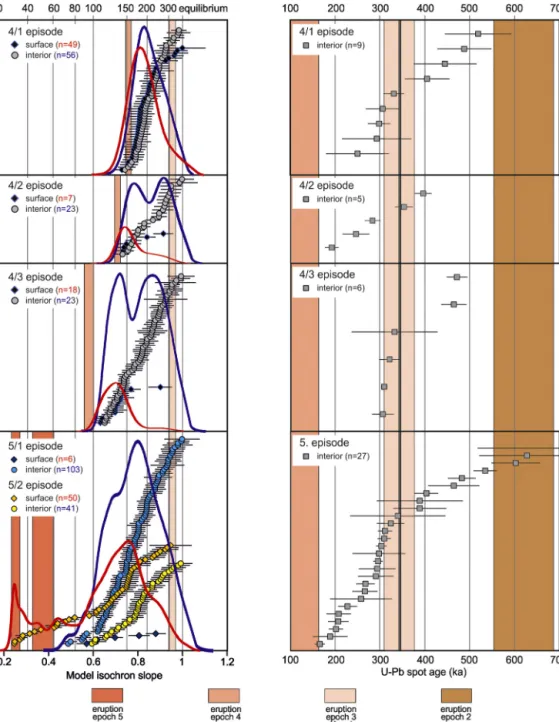

In general, new results confirm the protracted crystallization timescale suggested by a more limited number of zircon dates from the youngest eruption products (Harangi et al., 2015a). In addition, this combined database provides evidence that zircon crystallizationdatesgobacktoca.600ka.Agepopulationsofindi- vidual eruptiveepisodes usually display a polymodaldistribution with no apparent crystallization gap (within the uncertainty of the age data) in the probability density distribution curves con- structedforeacheruptiveepisode(Fig.2).Importantly,themodes forcrystalsurfaceagesareverysimilartothosederivedfrominte- riors,albeitinterioragesareslightlyoffsettoolderages.However,

Fig. 2.RankorderplotsforU-Thmodelages(representedasmodelisochronslopestoincorporate1σuncertaintysymmetrically;leftpanel)andforU-Pbspotages(right panel;1σ uncertainty)ofzirconinteriorsandsurfacesfromtheYCEPsamples.TheU-Thmodelagesaresuperimposedbyprobabilitydensitypopulationcurves(red:zircon surfaces;blue:zirconinteriors)obtainedbyDensityPlotter(Vermeesch,2012).Eruptionagesoferuptionepochs(Harangietal.,2015a;Molnáretal.,2018,2019)areshown bycolouredverticalbars.

where multiple analysisspots were placed onto crystal interiors, theyoftendisplaysignificantyoungingfromcoretorim(Appendix Fig. A.1). Within individual grains, spot ages range over several 10’stoeven100’skyr(AppendixFig. A.1).Althoughourdatasetis certainly biasedtowards dates<350ka(asweperformedmostly U-Thanalyses andlimitedU-Pbdating), wefound onlyfewdates

>400 ka(Fig. 2).The majorityof theobtainedU-Thmodeldates arebetween350kaand100kaandonly<10%fallbetween100 and30ka.

Statistical deconvolution of zircon surface crystallization age spectra using the mixing model of Sambridge and Compston (1994) identifies modes (Appendix Fig. A.2) for the eruptive episodes between 160and 95ka (epoch 4), predating the erup- tionagebyabout10-40kyr.Thisisalsothecasefortheyoungest

eruptive epoch 5 (57–30 ka), but zircon rim and interior crys- tallization ages display more complex distributions compared to those of epoch 4 due to the intrinsically smaller U-Th age un- certaintiesforyounger crystals.The dominantagepopulations in epoch5lie between200and100ka(∼75%),whereasonlyalim- itedsubset(∼12%)ofsurfaceagesis<75ka.Fourmodesat33±1 ka,62±2ka,114±1kaand176±1kaareidentified.Althoughthe identificationofagemodesdependsonthenumberofzircondates andtheirprecision whichoftenlimitstheirsignificance(Kentand Cooper,2017).WeusedKolmogorov–Smirnovstatisticaltestingto compare zircon age populations of successive eruptive episodes (Appendix Fig. A.3). We found that in all cases the compared populations were indistinguishable at the 95% confidence level.

Noteworthy,theprogressivelyyoungervolcanicformationscontain

R. Lukács, L. Caricchi, A.K. Schmitt et al. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 565 (2021) 116965

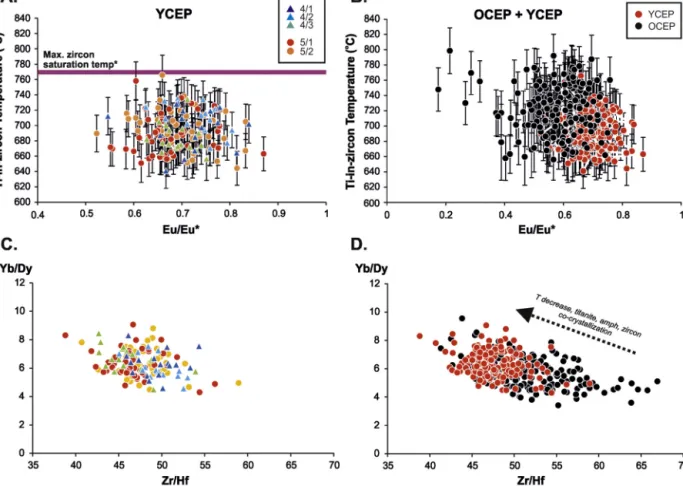

Fig. 3.Zircongeochemicalsignatureofdistincteruptiveepisodes(from4/1to5/2)ofYCEPintheleftpanels(A, C)andcomparisonoftheYCEPandOCEPzirconchemistry atrightpanels(B, D).Ti-in-zircontemperatures(FerryandWatson,2007)werecalculatedusingaTiO2=0.6andaSiO2=1.Zirconsaturationtemperaturewascalculated fromglasschemistryoftheyoungesteruptionproductsoftheYCEP(Harangietal.,2020)followingthemethodofBoehnkeetal.(2013).Usingthetwoend-memberglass compositiondataofHarangietal.(2020),thecalculatedzirconsaturationtemperaturevaluesareintherangebetween710and770◦C.InFig.3A,themaximumzircon saturationtemperatureisshown.

zircons with the age population found in the previous eruption products. Thissuggestsacommonlong-livedmagmareservoir, in whichsuccessive volcanicepisodeswere fedby magmas contain- ing newly crystallized and older zircon population. Overall, this continuous recyclingproduces awiderrangeofzirconcrystalliza- tionagesinyoungereruptionscomparedtotheolderepisodes.

The chemical composition of the YCEP zircons shows similar variability throughout the episodes of volcanic activity between 160and30ka(AppendixTable A.2;Fig.3;and AppendixFigs. A.4- 6). The Hf concentrations in the analysed crystals range from

∼8500to11500ppm,andEu/Eu*isbetween0.5and0.9(mostly between 0.6 and 0.8; Fig. 3A), indicative of co-crystallizing zir- con, plagioclase and titanite. The Yb/Dy values cluster between 4.5and9,correlatingpositivelywithHfconcentrations,andnega- tivelywithTh/U(Fig.3).Th/Uratioofzircondependsprimarilyon themeltcompositionandtherefore,reflectshowevolvedthemelt fractionisfromwhichzirconscrystallized (Reidetal., 2011;Reid andVazquez,2017).CiomadulYCEPzircondisplays Th/Ubetween 0.4and1.5, withabout80% ofdatafalling inthe rangefrom0.4 to0.8(AppendixFig. A.5).Suchvaluesindicatecrystallizationpri- marilyfromevolved, rhyoliticmelt,andzirconwithhighervalues (>0.8)formedfromalesssilicic,daciticmelt.

The Ti-in-zircon thermometer (Ferry and Watson, 2007) was appliedusingaTiO2=0.6andaSiO2 = 1toinferzirconcrystalliza- tion temperatures. The TiO2 activityvalue isestimated based on theglass Ticontents usingthemethodologyofHaydenandWat- son (2007;Appendix A). Inall eruptiveepisodes,afairly uniform temperaturerangebetween650and740◦C (mean= 693±25◦C;

AppendixFig. A.4)isobtained.Thetemperaturevaluesshowapos-

itivecorrelationwithTh/U,andnegativecorrelationswithHfand Yb/Dy, but no systematic variation with Eu/Eu* (Fig. 3). Zircons fromtheolder,1000–330kaeruptiveperiod(OCEP;AppendixTa- ble A.2; Fig.3; Appendix Figs. A.4-6) havesimilar trace element composition to YCEP zircons, but with more variance and slight overallshiftstohighercrystallizationtemperatures(∼650–780◦C;

mean = 720 ±32◦C; Appendix Fig. A.4), lower Hf (7000–11000 ppm), Yb/Dy (3.4–9.6; Fig. 3), Eu/Eu* (0.17–0.83; Fig. 3), Ce/Ce*

(AppendixFig. A.6)andhigherTh/U(0.23–1.79;AppendixFig. A.5).

5. Modellingzirconcrystallization

Rate of magma input and the thermal state of the crust are primary factors controlling the nature of subvolcanic plumbing systems,includingthe volume oferuptible magma (Annenet al., 2006; Annen, 2009; Karakas et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2020b).

The duration of zircon crystallization, i.e. the zircon age spread has shownto be a key proxy to constrain the magma fluxes by the comparison with modelled zircon age distributions obtained fromthermalmodelling(Caricchietal.,2014;Weberetal.,2020a).

ThestatisticallyrobustzircondatasetofCiomadulprovidesanex- cellentopportunitytoinvestigatethethermalhistoryofamagma reservoirbeneathasmall-volumevolcanicsystem. Thermalmodel calculationssimulating the prolonged injection of magma in the crustwereperformedusingthemethoddescribedinKarakasetal.

(2017) andLaumonieretal.(2019).Magmais injectedincremen- tallyinthecrustovertheestimatedlifetimeofthemagmaticsys- tem(i.e.2Myr).Heatconductionbetweenthecrust andintruded magmasovertimeisinvestigatedbyatwo-dimensional,fullyim-

plicit,forward,transientheatdiffusioncodeusinga finitevolume scheme(Patankar, 1980). Weconsider atwo-dimensional domain (60km× 60km)witha40kmthick crusthavinga steady-state geothermwith0◦Csurfacetemperatureandconstantheatfluxat themantle-crustboundary.Weemplaceddikesandsillsincremen- tally and randomly using a stochastic andinstantaneous scheme over a total of 4 Myr intothe lithosphere following a two-stage process. First,basalticmagmas were emplaced inthelower crust for 2 Myr, which increases the temperatures of the entire crust (geothermal gradient was elevated by about20% with respect to the normal one).In the second stage, the model switches to in- trusion ofdaciticmagmas intotheuppercrust (7–15kmdepths;

injectiontemperature950◦C). The silicicmagma isconsidered to represent the product of fractionation of basaltic magma in the lowercrust.Thecalculateddurationofzirconcrystallization ises- sentiallycontrolled bytherateofheat(i.e.magma)inputintothe crust. Thus,adecreaseofthetemperatureoftheinjected magma canshortentheperiodoverwhichzirconcrystallizes.However,the decreaseofenthalpycontentofmagmaforadecreaseoftempera- ture with 50◦C is only ofthe order of 3% (Caricchi and Blundy, 2015). This implies that our flux estimates would vary by only a few percent considering temperatures for the injected magma that arewithinabout100degreesfromthetemperatureusedfor thisstudy.Passivetracers(40m×40m),addedwiththemagma, recordtheevolutionoftemperatureintimeindifferentportionof thesystem. The numberoftracerswitheach intrusionvariesbut their total numberisalways larger than 300. Therateof magma inputinthecrustwasbetween10−2and10−4 km3/y.

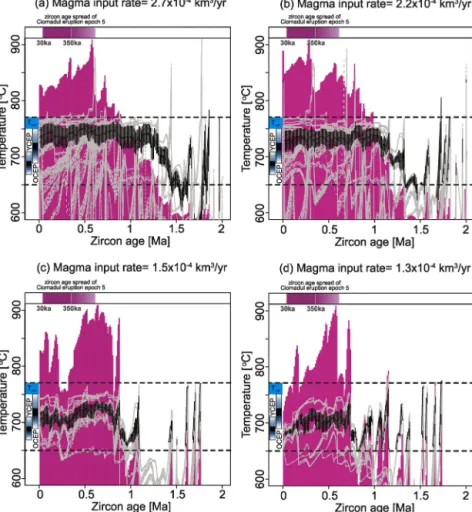

We use the time-temperature record of each tracer to calcu- latethenumberofzirconcrystallization agesavailableforanalysis (Fig. 4). Thenumberofmeasurablezirconages variesproportion- ally tothe rate ofzircon crystallization followingthe parameter- ization proposed by Tierney et al. (2016). As a consequence, a smaller number ofmeasurable ages iscalculated when the tem- perature of a tracer approaches the solidus (Appendix Fig. A7).

Zircons aremodelledto growfromamaximumtemperaturethat can varybetween770◦C downto solidustemperature(∼650◦C).

Weassumethatatthemomentoferuption,alltracerswithatem- perature within the zircon crystallization range are erupted. This impliesthat all tracersthatcooled belowsolidus beforeeruption will not contribute to the final distribution of measurable ages sampled by an eruption (Fig. 4). The model neglects convection within the reservoir, as the effect of convection on the thermal evolution ofthe magmatic systemhas been shown to be minor (Caricchietal.,2014,2016).Highfrequencymodulationofmagma fluxes(whichare infact simulatedinourmodelwheretheinput ratechangesfrominfinityduringinjectionto0duringbreaks),are notvisibleinthemodelledpopulationofzirconagesfortwomain reasons: the thermal inertia of a magmaticsystem andthe ana- lytical uncertainty that smoothes the distribution of zircon ages.

Other sensitivity tests were already performed in Caricchi et al.

(2014,2016).

Ourcalculationsshow that withincreasing rateofmagma in- put, tracers spend longer time within the zircon crystallization rangeandthereforetherangeofagesover whichcontinuouszir- concrystallization isrecordedincreaseswithmagmaflux(Fig. 4).

Additionally, atthehighestfluxes,few tracersthatinitiallycooled belowsolidusarere-heatedbeforeeruptiontotemperaturescom- patiblewithzirconcrystallization.Theaveragetemperatureofthe tracers(i.e.ofthemagmaeventuallysampledbyaneruption)ini- tiallyincreasesandthenreachesratherconstantvaluesinallmod- els (Fig. 4). The rateof temperatureincrease atthe beginning of themodeldependsonthemagmaflux.Theplateauvalueofaver- agetemperaturealongwithitsstandarddeviationsinthedifferent modelsdecreasesslowlywithtime:therateofthisdecreaseagain dependsontheaveragerateofmagmainput(Weberetal.,2020a).

6. Discussion

6.1. Episodicvs.continuouszirconcrystallization

Zirconagedistributionsareoftendifficulttointerpretinterms whetherthey indicateepisodicorcontinuous crystallization(Kent and Cooper, 2017). Due to the uncertainties of the U-Th model dates,brief(lessthanfewthousandyears)perturbationsinmagma temperature or chemistry cannot be resolved. A hiatus in zir- con crystallization could be due to various processes (Reid and Vazquez,2017):

1. local Zr depletion in the surrounding melt, especially under conditionswheremeltconvection ceased(littleto noreplen- ishmentoffreshmagma);

2. increasingtemperatureaboveZr-saturationormixingwithZr- undersaturatedmeltduringrecharge(inducingresorption);

3. zirconentrapmentbyamajorphenocrystphase,orintoasub- soliduspartofthemagmareservoir.

Episodic vs. continuous zircon crystallization is usually inter- pretedbased onvarious statisticaltechniques such asprobability andkerneldensitydistributionsofzirconages,isochronslopes or the Sambridge and Compston (1994) mixture modelling. Frey et al. (2018) suggested episodic zircon crystallization separated by longsubsolidusconditionsfortheyoungestvolcanismofDominica (LesserAntilles)basedonthehiatusesobservedinthezirconspec- tra. Incontrast tothe punctuatedzircon age distributions shown byFrey etal.(2018),the Ciomadulzirconsurface dateslack pro- nouncedgapsintheagedistributions.However,wecannotexclude the possibility that punctuated crystallization was occurring on timescale shorter than the uncertainty on zircon age determina- tions (i.e. in <10 kyr scale). Within the magmatic zoning, only inconspicuous resorption surfaces are occasionally present, sug- gesting partial dissolution and renewed crystallization of zircon crystals,possiblyduetomagmarecharge.Localchemicaldepletion ofthemelt(ReidandVazquez,2017),interrupting zirconcrystal- lization,couldalsooccurduetohighcrystallinity(>40–50vol%)in themagmareservoir,suppressingbulkmagmaconvection.Lullsin zirconcrystallizationcanbecausedbypre-eruptiveheatingabove the zircon saturation temperature (710–770◦C; Fig. 3.), and this mightbeindicatedbyzirconsurfaceagessignificantly(withafew 10’kyr) predating the eruption. This isrecognized forseveral of the Ciomadul samples (Harangi etal., 2015a) and also for other volcanicsystems(e.g.,Friedrichsetal.,2020;Gençalio˘glu-Ku ¸scuet al., 2020; Weber et al., 2020a). Pre-eruptive reheating may stop zircon crystallization or even dissolve the outermost zircon lay- ers. Alternatively, very thinnewovergrowths maygo undetected when integratingdata over the outer ∼4 μm deepcrater gener- atedduring SIMSdepthprofiling.Furthermore,newly formedzir- concrystals growing just before eruption mightbe toosmall for separationandthereforemaybeunderrepresentedintheobtained zirconages.

Basedonzirconagespectraandtexturalevidence,thefavoured scenario for Ciomadul is prolonged (over several 100’s kyr) zir- concrystallizationinalong-lived,mostlyhighlycrystallinemushy environment withlimited convection,where occasional interrup- tions in zircon crystallization were due to localized recharge, Zr depletion in the melt or shielding by solidification. The succes- sive zircon U-Th and U-Pb dates from the YCEP dacites overlap within analytical uncertainties in ranked order distribution plots (Fig.2). Thus, thezirconage spectraare permissiveofprotracted andquasi-continuouscrystallization(>350kyr).Bothinteriorand surface zircon ages record long crystallization histories for each eruption andhencethe overall timescale of zirconcrystallization

R. Lukács, L. Caricchi, A.K. Schmitt et al. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 565 (2021) 116965

Fig. 4.Resultsofthethermalmodellingperformedfordifferentmagmainputrates(decreasingfrompanelatod).Thegreylinesshowtheevolutionofthetracersthat arewithinthezirconsaturationtemperaturerangeafter2Myrofmagmainjection(timeincreasingfromrighttoleft).Theblacklinesandthebarshowtheevolution ofmeantemperatureand standarddeviationduringthe2Myrofmagmainjection,respectively.Thehistograminpinkshowsthe calculateddistributionofpotentially detectablezirconagessincetheonsetofmagmainjection(noteyaxisshowstherelativefrequencyinthiscase).Thedashedlinerepresentstherangeofzirconsaturation temperatureusedforthecalculations.Thebarsabovethepanelsshowthezirconagespreadinthesamplesoferuptionepoch5withintheYCEP.Notethatages>350kaare underrepresented,asU-Pbdatesarelimitedinthedataset.Theagespreadofthenaturalzircondatahasthebestfitwiththemodelleddurationforthelowestmagmainput rate(paneld).AveragezirconcrystallizationtemperatureswiththestandarddeviationcalculatedbasedonTi-in-zirconthermometrydata(AppendixFig.A.4)fortheYCEP andOCEP,respectively,aswellasthecalculatedzirconsaturationtemperaturerange(Fig.3)arepresentedontheleftsideofthediagramsforcomparisontothemodelled averagetemperature.

can be considered as a robust indication of magmatic longevity within the temperature range where zircon is saturated. Quasi- continuous zircon crystallization is also evident from individual crystals, includingthose from a ca. 95ka old lava dome. A pro- gressiverimwardsyoungingisobservedformultipleanalysisspots on different crystals, whichyielded ages that decrease from 293 ka to 128 ka(Appendix Fig. A.1). This suggeststhat zircon crys- tals were in contactwithmelt atleast intermittentlythroughout their residence time and thus, a significant part of the magma storageoccurredattemperaturesabovethe solidus.In thissense, crystallizationcanberegardedascontinuous(i.e.withouthiatuses significantlylonger thantheuncertaintyonsingleagedetermina- tions)inthereservoirasawhole.Inordertogeneratestatistically significanthiatusesinthedistributionofzirconages,gapsinzircon crystallization(orzirconresorption)wouldhavetobeextensiveto affecta large portionof themagma reservoir,which, however,is notobservedinthedistributionofzirconages.

To maintain a long-lived reservoir above its solidus, continu- ous magma input, i.e.repeated magma recharge is required.Al- though the Ciomadul magmastorage systemwas maintainedvia recharge events for protracted time, episodically more intensive magmainput(e.g.,>200◦Creheatingbeforethe135kaCiomadul Miclavadomeextrusion;Kissetal.,2014)likelytriggerederuptive events.

6.2.Zirconcrystallizationinalong-lastingsubvolcanicmagma reservoir

Thecommonoccurrenceoflowtemperature(650–750◦C)min- eral assemblages and felsic crystal clots with inter-crystalline glassesin the Ciomadul dacitessuggest that at least partof the subvolcanicmagmareservoirwaskeptathighcrystallinity(Kisset al.,2014).Periodicrechargeeventsledtopartialremeltingofthe majormineralphases(mostlyplagioclase,amphiboleandbiotite), rejuvenatingpartsofthereservoirtobecomeeruptible.Eruptionof magma occurredfromwell-mixed domains within themagmatic systemwithantecrysticmajorandaccessoryminerals.Zirconpop- ulations with various crystallization ages formed during episodic mushreorganizationthatnotnecessarilycausederuptionbutcoa- lescenceofdistinct partsofthe reservoirsduring convectingstir- ring episodes(Vazquez andReid, 2004; Bachmann andBergantz, 2006).

The efficiencyof pre-eruptive rejuvenation is reflected by the wide range of zircon dates in all samples. The heterogeneity of zirconages andvariation intrace elementcompositionsin single hand-samplesimplythatmultiplezircongenerations becamesuc- cessivelymixedandultimatelyentrainedintotheeruptedmagma.

Bulk rock compositions are fairly homogeneous and variations in zircon chemistry are similar in each eruption product (Fig. 3

Fig. 5.Zirconcrystallizationages(with2seuncertainty)ofOCEPeruptionproductsbasedonU-PbgeochronologydataofLukácsetal.(2018).Theorangetrianglesbelowthe maindiagramrepresentthe eruptionages(cf.Fig.1)withuncertaintiesgivenbyMolnáretal.(2018).Abbreviations:AB=TurnulApor;BAL=Balvanyos;BH=Puturosul;

NH=DealulMare;BL=Baba-Lapo ¸sa;MB=Bixad;MB-M=Malna ¸s;PD=Pili ¸sca;NM=MurgulMare(Fig.1).

andFig. A.5 inSupplementary Material), suggestingefficient pre- eruptionmixinginthemagmareservoir.Glassmajorelementdata (matrixglassandsilicatemeltinclusions;Vinkleretal.,2007;Ha- rangi et al., 2020; Karátson et al., 2016; Laumonier et al., 2019) oftheeruptiveproductsarerhyodacitictorhyoliticandsuchcom- positionalvariation issupportedalsoby themineralcargoshow- ingconsiderablecompositionalrange(e.g.,amphiboles;Kissetal., 2014;Laumonieretal.,2019).ZirconTh/Uvaluesineacheruption product vary widely implying mixed crystalpopulations that are derived fromvariously evolvedsilicic meltfractionsinthecrystal mushbody.Zirconcrystalsareexpectedtooccurmostlyimmersed in the melt phase because of their small size (Reid etal., 1997;

Bindeman, 2003; Claiborne et al., 2010), and they remain stable forprotracteddurationsatthedominantlylow,nearsolidustem- perature (700-750◦C)ofthe crystalmush.This issupported also bytheresultsofthermalmodellingwhichindicateratherconstant average temperatures (650–750◦C; Fig. 4) in the crustal magma reservoirfor100’softhousandsofyears.

Rejuvenation events were likely brief, particularly when high temperature mafic magmas were injected into the crystal mush reservoir. Thebimodalityoftheamphibolepopulation(Kiss etal., 2014; Laumonier et al., 2019) in the dacites suggests that the erupted magmas contained a mixture of components from the low-temperaturefelsicmushandthehotrechargemagmas.Note- worthy, we havenot found zircons withrelatively hightempera- ture (>750◦C) nor strong resorption within zircon crystals, sug- gestingrapidpre-eruptionreactivation.Nevertheless,ifthesystem ishighly crystallized,magmainjectiondoesnotnecessarilyresult in an increase of temperature because all heat is consumed for meltingthecrystals.

Similarlylong-livedmagma reservoirshave beenidentifiedfor otherandesitictodaciticvolcanicsystemssuchasMountStHelens (Washington, USA;Claiborneetal.,2010),Lassen Peak(California, USA;Klemetti andClynne,2014),Nevadode Toluca,Mexico(We- ber et al., 2020a), the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex (Central Andes; Kern etal., 2016; Tierney etal., 2016), theSoufriére vol- cano (St.Lucia, Lesser Antilles;Schmitt etal., 2010) and theMt.

Erciyes(CentralAnatolia,Turkey;Friedrichsetal.,2021),aswellas forthe largevolume Fish CanyonTuff(Colorado,USA; Bachmann etal.,2007;Wotzlawetal.,2013)andYoungerTobaTuff,Indonesia (VazquezandReid,2004;ReidandVazquez,2017).Althoughthese volcanicsystems yieldedmagma volumesinscale from10tothe

few 1000km3,they all have a commonfeature that theseerup- tions tapped cool (just above the solidus) and wet calc-alkaline silicic magmas (LipmanandBachmann, 2015; Reid andVazquez, 2017).ThisfeatureholdsalsofortheCiomaduldacites(Kissetal., 2014;Laumonieretal.,2019).

6.3.Relationstotheoldermagmareservoirs

WithinthestudiedzirconpopulationoftheYCEPsamples,there aresome zirconinteriors crystallizedbeforethe 344±33kaApor eruption(Molnáretal.,2018),thelastknowneruptionintheOCEP phase (Fig. 2and5). Thus, they are presumablyderived fromits precursormagma body.Much olderzircon crystals(derived from Epoch1 and2 of OCEP, Fig. 5), on the other hand, are scarcely observed in the YCEP samples. This can be explained either by theperipheralandisolatedpositionoftheOCEPmagmareservoirs beneaththe Ciomadulvolcanic dome field exceptfor Apordome thatiswithintheCVC(Fig.1)orbecausethesereservoirswereal- readysolidifiedatthetimeoftheYCEPeruptions.Thus,theYCEP subvolcanicmagmabodycanreasonablybeinterpretedasthecon- tinuation of the Apor system that existed during the apparently long eruption hiatus before YCEP volcanism (ca. 160 ka; Molnár etal., 2019). The Aporeruption contains zircon with ages >500 ka,whichcovertheeruptionandzirconcrystallizationagesofthe previous OCEP Epoch2 eruptions (Fig. 5). Allpreceding eruption materials ofOCEP show overlapping zirconage spreads.This im- pliesacontinuityofmagmastorageandefficientrecyclingofOCEP intrusionsinthesubsequenteruptiveepochs.

The apparent continuity between OCEP and YCEP systems has two important implications: 1) zircon crystallization already started ≥1.5 Ma ago; 2) the spatial overlap between eruption centreswithin theCVDFsincetheAporeruptionsuggestshomog- enizationofacommonmagmareservoirwherezirconwithdiffer- entagesbecameefficientlymixedbefore eruptions.Therefore,we proposethat the∼100km2 CVDFrepresentsthe subaerialmani- festationofanextensivemagmareservoirintheuppercrust that hasbuiltup over 1.5–2 Myr. Thisoccurred inan alreadyslightly heatedcrustasaresultofthenearbyPili ¸scavolcanism(Fig.1;Pre- Ciomadulvolcanism).Althoughsomepartsofthismagmareservoir becamecertainlysolidified,therewerealwaysportionswithsuffi- cientmeltpresentthatallowedepisodicrejuvenationanderuption.

R. Lukács, L. Caricchi, A.K. Schmitt et al. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 565 (2021) 116965

The thermal condition of the long-lived magma reservoir be- neathCiomadulduringtheYCEPstageappearstohavebeenfairly low,as indicated bythe generallylow Ti content ofzircons (Ap- pendix Figs. A.4 and A.6) andthe abundance of a felsic mineral assemblage withcompositionsindicativeofcrystallizationatrela- tivelycoldenvironment(<750◦C;Kissetal.,2014).Thisisconsis- tent withprolonged existence ofa felsic crystalmushjust above the solidus that was growing by progressive magma input (Car- icchi et al., 2014). Felsic glomerocrystic crystal clots (consisting of plagioclase,low-Alamphibole, biotite,accessory mineralssuch astitanite,zirconandapatiteaswell asoccasional quartzandK- feldspar;Kissetal.,2014)occurfrequentlyinthedomerocksand they areinferred torepresentthisevolvedcrystalmushmaterial.

Theinter-crystalline vesiculatedglasshasmostly rhyoliticcompo- sitions (Laumonieret al., 2019) and represents the evolvedmelt fraction in the crystal mush, where zircons remained stable for a long time. On theother hand,zircon fromthe OCEP stage has slightly higher Ti abundances and trace element signatures indi- catingderivationfromlessevolvedmeltcomparedtoYCEPzircon (Fig.3;AppendixFigs. A.5-6).Theserocksshowalargervariability inbulk rockcomposition (Molnár etal.,2018) andtypically have plagioclaseandamphibolepairs(Harangietal.,unpubl.data)pro- viding highercrystallizationtemperatures thanthose intheYCEP dacites. Thus, there isa temporal shift to more evolvedand ho- mogeneous magma and lower temperature condition from OCEP toYCEP.Basedonthemodelresultsdiscussedbelow,thissuggests that the system hasgrown with time, leading to an increasingly homogeneousmagmacompositioncharacterizedbyrelativelycon- stant andlow temperatures consistent withtheresults ofWeber etal.(2020b).

6.4. MaintainingtheprotractedCiomadulreservoirbasedonthermal modelling

ThezirconU-PbandU-ThmodelagesshowthatallYCEPerup- tionsbetween160and30kasamplezirconupto600-500kaold andthat thezirconage rangeincreasesforprogressivelyyounger eruptions.Thismeansthatinadditiontonewlycrystallizedzircon, antecrysts from earlier episodes were recycled (Fig. 2). Such an agespreadsuggestsquasi-continuous zirconcrystallizationover a protracted (several100’skyr)timescaleandeffectivepre-eruption mixingwithin theCiomadulmagmareservoir.AlthoughKent and Cooper(2017) proposedthatuncertaintiesofindividualzirconages precludeassigninguniquethermalhistoriestosuchdata,Weberet al.(2020a) showedthatthereliabilityofnaturalzirconagedistri- butionsstronglydependsonthesamplingsize.Therefore,thetotal durationofquasi-continuouszirconcrystallization(asrecordedby the zircon age spread) and the average temperature within the magmareservoir(reflectedbythecrystallizationtemperaturescal- culatedbyTi-in-zirconthermometryaswellasmajormineralther- mometry;thisstudyandKissetal.,2014;Laumonieretal.,2019) are solid proxies to estimate the thermal evolution and average rate of magma input into the plumbing system and the volume ofmelt withinthe reservoir(Fig. 4). Weconsidered thatthe pre- Ciomadulvolcanismalreadyheatedupthecrust.Noteworthy,none of theCiomadul eruption sampledzircons fromthe older(>1.65 Ma) magma reservoir and the Ciomadul magma has also a dis- tinctivecompositionalfeaturecomparedtothe>1.65Maandesitic todacitic rocksofSouthHarghita(Molnár etal.,2018).Thus, the Ciomadulmagmasystemdevelopedindependentlyfromtheolder volcanism but in an area with an already elevated geothermal gradient. Therelatively homogeneous composition oftheerupted products since 600 Ma (epoch2; Molnáret al., 2018,2019) also suggestsanelevatedgeothermalgradientalreadyatthebeginning ofvolcanism,otherwisewiththelowmagmafluxindicatedbyour modelmoretime wouldbe requiredbothtomatchthespreadof

zirconages andtheir measuredchemical homogeneity(Weberet al.,2020b).

The total spread in zircon ages sampled by the last eruption stage (eruptive epoch 5) of Ciomadul is about 600 kyr and the model that produces a similar spread in zircon ages is that for thelowest average rateofmagmainput testedhere (1.3× 10−4 km3/yr; Fig. 4d). Further support for this relatively low rate of magma input comes from crystallization temperature estimates.

The calculationsperformed with thisrate ofmagma input show that theaverage temperatureover thelast 0.5Ma should be be- tween 670 and 720◦C, which is remarkably similar to that ob- tained by the Ti-in-zircon as well as the major mineral ther- mometers (Figs.3 and4d). Higher magma fluxes wouldproduce longerperiods ofcontinuouszircon crystallization andhigherav- erage temperature estimates. As an example, if the magma flux wastwotimeshigher(i.e.2.7×10−4 km3/yr),zirconsagescould spreadoverabout1.5Ma,withaveragetemperaturesoftheorder of720-750◦C(Fig.4a).Aslowerratesofmagmainputinthecrust over longer timescales (i.e. >2 Ma) could potentially also yield a similar spread in zircon ages andaverage temperatures, 1.3 × 10−4km3/yrisconsideredasamaximumestimate.Thisestimated magma flux is significantly lower than calculated forNevado de Tolucavolcano(Mexico),whichwasactiveforacomparabletimes- pan asCiomadul, but produced six-times larger erupted magma volume(60km3;Weberetal.,2020a).

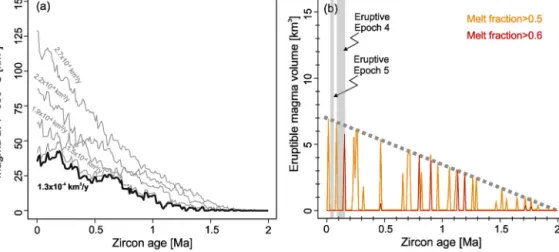

Atthepreferredmodelrateof1.3× 10−4km3/yrmagmaflux, about 260 km3 magma was injected in the upper crust over 2 Myr. The melt fraction in this reservoir and the volume of the eruptible magmawere calculated forthistimespan based onthe thermalmodelpresentedinthisstudy.Thevolumeoftheeruptible magma (i.e., the magma fraction having >50% melt at >800◦C) along withthe fraction of supersolidus,but uneruptiblematerial (highcrystallinitymushat>670◦C)inthereservoirbothincrease withtimeandjustbeforetheeruptiveepoch4theyreach∼6km3 and35km3,respectively (Fig.6).Thisisconsistent withthe pro- ductivity ofepoch 4 resulting in 4–5km3 cumulative volume of extrusive material for a timespan of 70 kyr from 160 to 90 ka (Szakácsetal.,2015;Karátsonetal.,2019;Molnáretal.,2019).In- termittentevacuationofsmallvolumesofmagmaarenegligiblefor thethermalstate oftheentiremagmareservoirandtheeruptive lossofmagma iscompensated by injectionoffreshmagma.This meansthat sufficientpotentially eruptible magmaremainedafter 40kyrofdormancyattheonsetoftheeruptiveepoch5.Forcon- tinuedmagma injection, we suspect that similar conditionsexist presently beneathCiomadulassupported by seismicandmagne- totelluric models (Popa et al., 2012; Harangi et al., 2015b). The estimated magma and melt volume derived from thermal mod- ellingofzircon crystallization iscomparable, although a littlebit lower,thancalculatedbyLaumonieretal.(2019) basedonmagne- totelluricresultsandconductivityexperiments.Thecomparatively smallvolumeoferuptedmaterialproducedbyCiomadulsofar(ca.

8–10km3 asdetermined by Szakács etal., 2015;Karátson etal., 2019; Molnár et al., 2019) results in an extrusive-intrusive ratio of1:25to 1:30,lower thanthe1:1 to1:16 ratioofaveragecon- tinentalvolcanism (White etal., 2006), buthigher thanthe 1:75 ratioproposedforthewaningstagesoftheAltiplano-Punamagma system (Tierney et al., 2016). Remarkably, based on seismic and stratigraphicdata, similar volcanic to plutonicratios were calcu- latedforPinatubo(Morietal.,1996;WolfeandHoblitt,1996)and Nevado del Toluca (Weberet al., 2020a), which produced dacitic volcanicrocksakintoCiomadul.

The dacitic upper crustal reservoir of Ciomadul seems ther- mally primed and therefore potentially capable of mobilizing up to a few km3’s of eruptible magma upon recharge. Injection of hot mafic magma asevidenced by petrology andmineral chem- istryof the past eruption stages (Kiss et al., 2014; Laumonier et

Fig. 6.TimeevolutionofsupersolidusanderuptiblemagmavolumesintheCiomadulmagmaticsystembasedonthermalmodellingresults.a)Volumeofmagmaabove soliduscalculatedforthesimulatedrangeofmagmafluxes.Theinferred1.3×10−4km3/ymagmafluxover2Myrledtoaround30-40km3magmainsupersolidusstate withinthemagmareservoirofestimated260km3volume.b)Volumesoferuptiblemagmacontaininginexcessof0.5(orange)and0.6(red)meltfraction.Thespikes correspondtotherandominjectionofanewsillintotheplumbingsystem.Notethatthemagmasystemiscapabletoproducecontinuouslylargervolumeoferuptible magmareaching6to7km3whentheeruptiveepoch4and5occurredatCiomadul.

al., 2019) is a powerful triggermechanism causingrapid (within months to years) rejuvenation. Further research is necessary as apparently inactive volcanoeswithprimed magma reservoirs like Ciomadulcould revive fast evenafter long(in humanterms) pe- riodsofquiescence,whichhassignificantimplicationsforvolcanic hazardassessments.Ourresultsurgeattentiontootherareaswith long-dormant volcanoes, which could have unnoticed, but long- livingandstillactivesubvolcanicmagmareservoir.

CRediTauthorshipcontributionstatement

R. Lukács: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. L.Caricchi:

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. A.K.Schmitt: Data curation, Writing – review

& editing.O.Bachmann:Writing – review& editing.O.Karakas:

Investigation,Software.M.Guillong:Datacuration.K.Molnár:Re- sources, Writing –review & editing.I.Seghedi:Writing –review

&editing.Sz.Harangi:Supervision,Visualization,Writing–review

&editing.

Declarationofcompetinginterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompetingfinan- cialinterestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedto influencetheworkreportedinthispaper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to the members of the MTA-ELTE Vol- canological ResearchGroup (Budapest) fortheir helpsduring the field andlaboratoryworks.I. Seghedi benefitedby agrant ofthe Ministry of Research andInnovation, CNCS–UEFISCDI, project no.

PNIII-P4-ID-PCCF-2016-4-0014,withinPNCDIIIIandR.Lukácsben- efited by theJános Bolyai Research Scholarship ofthe Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The HIP facility atHeidelberg University is operatedundertheauspicesoftheDFGScientificInstrumentation andInformationTechnologyprogramme.We areverygratefulthe three reviewers, MaryReid,MarkSteltenandCaseyR.Tierneyfor theconstructivecommentsandsuggestions,whichhelpedtoclar- ifyourresults.

Funding:Thisworkbelongstotheresearchprojectssupported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office in

Hungary(No.K116528,No.PD121048andNo.K135179);theEu- ropean Union, KMP project (No. 4.2.1/B-10-2011-0002); and the European Union and the State of Hungary,via the European Re- gionalDevelopmentFund(GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00009).LChasre- ceived funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under theEuropean Union’s Horizon2020research andinnovation pro- gramme(grantagreementNo.677493- FEVER).

Appendix A. Supplementarymaterial

Supplementarymaterialrelatedtothisarticlecanbefoundon- lineathttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.116965.

References

Annen,C., 2009.Fromplutons tomagmachambers:thermal constraintsonthe accumulationoferuptiblesilicicmagmaintheuppercrust.EarthPlanet.Sci.

Lett. 284,409–416.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.006.

Annen,C.,Blundy,J.D.,Sparks, R.S.J.,2006.Thegenesis ofintermediateand sili- cicmagmasindeepcrustalhotzones.J.Petrol. 47,505–539.https://doi.org/10. 1093/petrology/egi084.

Bachmann, O., Oberli, F.,Dungan, M.A., Meier, M., Mundil,R., Fischer, H.,2007.

40Ar/39ArandU–PbdatingoftheFishCanyonmagmaticsystem,SanJuanVol- canicfield,Colorado:evidencefor anextendedcrystallizationhistory.Chem.

Geol. 236,134–166.

Bachmann,O.,Bergantz,G.W.,2006.Gaspercolationinupper-crustalsiliciccrystal mushesasamechanismforupwardheatadvectionandrejuvenationofnear- solidusmagmabodies.J.Volcanol.Geotherm.Res. 149,85–102.

Bindeman,I.N.,2003.Crystalsizesinevolvingsilicicmagmachambers.Geology 31, 367–370.

Boehnke,P.,Watson,E.B.,Trail,D.,Harrison,T.M.,Schmitt,A.K.,2013.Zirconsatura- tionre-revisited.Chem.Geol. 351,324–334.

Burgisser,A.,Bergantz,G.W.,2011.Arapidmechanismtoremobilizeandhomoge- nizehighlycrystallinemagmabodies.Nature 471,212–215.

Caricchi,L.,Blundy,J.,2015.TheTemporalEvolutionofChemicalandPhysicalProp- ertiesofMagmaticSystems.GeologicalSociety, London.SpecialPublications, vol. 422,pp. 1–15.

Caricchi,L.,Simpson,G.,Schaltegger,U.,2014.Zirconsrevealmagmafluxesinthe Earth’scrust.Nature 511,457–461.

Caricchi,L., Simpson,G., Schaltegger,U., 2016.Estimates ofvolumeand magma inputin crustalmagmaticsystemsfrom zircon geochronology:the effectof modelingassumptionsandsystemvariables.Front.EarthSci. 4.https://doi.org/ 10.3389/feart.2016.00048.

Cisneros de León, A., Schmitt, A.K., 2019. Intrusive reawakening ofEl Chichón volcano priorto its Holocene eruptive hyperactivity. J. Volcanol. Geotherm.

Res. 377,53–68.

Claiborne,L.L.,Miller,C.F.,Flanagan,D.M.,Clynne,M.A.,Wooden,J.L.,2010.Zircon revealsprotractedmagmastorageandrecyclingbeneathMountSt.Helens.Ge- ology 38,1011–1014.