262

Seminars in Cancer Biology 23 (2013) 262-269

Adaptation and learning of molecular networks

as a description of cancer development at the systems-level:

potential use in anti-cancer therapies

Dávid M. Gyurkó

1, Dániel V. Veres

1, Dezső Módos

1,2,3, Katalin Lenti

2, Tamás Korcsmáros

3and Peter Csermely

1,11

Semmelweis University, Department of Medical Chemistry, Tuzolto u. 37-47, H-1094 Budapest, Hungary;

2

Semmelweis University, Department of Morphology and Physiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Vas u. 17, H- 1088, Budapest, Hungary;

3Eötvös Loránd University, Department of Genetics, Pazmany P. s. 1c, H-1117

Budapest, Hungary

Abstract: There is a widening recognition that cancer cells are products of complex developmental processes. Carcinogenesis and metastasis formation are increasingly described as systems-level, network phenomena. Here we propose that malignant transformation is a two-phase process, where an initial increase of system plasticity is followed by a decrease of plasticity at late stages of carcinogenesis as a model of cellular learning. We describe the hallmarks of increased system plasticity of early, tumor initiating cells, such as increased noise, entropy, conformational and phenotypic plasticity, physical deformability, cell heterogeneity and network rearrangements. Finally, we argue that the large structural changes of molecular networks during cancer development necessitate a rather different targeting strategy in early and late phase of carcinogenesis. Plastic networks of early phase cancer development need a central hit, while rigid networks of late stage primary tumors or established metastases should be attacked by the network influence strategy, such as by edgetic, multi-target, or allo-network drugs. Cancer stem cells need special diagnosis and targeting, since their dormant and rapidly proliferating forms may have more rigid, or more plastic networks, respectively. The extremely high ability to change their rigidity/plasticity may be a key differentiating hallmark of cancer stem cells. The application of early stage-optimized anti-cancer drugs to late-stage patients may be a reason of many failures in anti-cancer therapies. Our hypotheses presented here underlie the need for patient-specific multi-target therapies applying the correct ratio of central hits and network influences — in an optimized sequence.

Key words: adaptation; anti-cancer therapies; cancer attractors; cancer development; epithelial-mesenchymal transition; interactome;

networks; signaling Abbreviations: BRAF, B-Raf protein; BRD4, bromodomain-containing protein 4; CDK6, cyclin-dependent kinase 6;

ERBB1, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERG, ETS-family oncogenic transcription factor; ERK, extracellular signal regulated protein kinase; FOS, FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog; FOXO3A, forkhead family transcription factor; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1; MMP2, matrix metalloproteinase 2; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; MYC, myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog protein; NES, nestin intermediate filament protein; p53, TP53 tumor suppressor protein; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PI3K, phosphatidyl-inositol-3'-kinase; PKM2, pyruvate kinase M2 isoform; RAS, small GTPase protein; RHOA, RAS- homolog gene family member A; TGFBR, Transforming growth factor-β receptor; TNC, tenascin C protein.

In this paper first we will describe cancer development as a two-phase phenomenon characterized by a first increased than decreased plasticity (or in alternative wording: by a first decreasing than increasing rigidity) at the systems-level. We will propose that cancer stem cells have the unique property to induce rapid and gross changes of their network plasticity/rigidity. Next, we will list the cancer- specific properties of molecular networks highlighting the adaptation of network structure and dynamics in various stages of cancer development as a model of cellular learning. Finally, we will highlight that different network-related anti-cancer strategies are needed to target early and late stage cancer cells, as well as cancer stem cells, and will list the possibilities to target all these cell communities.

1. Development of cancer as a learning process of increasing and then decreasing plasticity at the systems-level

Cancer cells are products of a complex cell transformation process. The starting steps of this process are often mutations or DNA-rearrangements, which destabilize the former cellular phenotype. As a result, a cell population with a large variability in

1

Corresponding author; Csermely.Peter@med.semmelweis-univ.hu

chromatinorganization(includingDNA-hypomethylation,histone modificationandchromatinstructure),geneexpressionpatterns andinteractomecompositionisformed.Thisheterogeneouscell populationischaracterizedbyanincreasedlevelofstochasticpro- cesses(noise),phenotypicplasticity[1–6],andbyanincreasein thenetworkentropyofprotein-proteininteractionnetworks(the definitionsoflocalandmoreglobalvariantsofnetworkentropysee in[7–9]).Higherdegree-entropyofsignalingnetworkswasfound tocorrelatewithlowersurvival of prostatecancerpatients[9], whichunderliesboththemedicalrelevanceandthegeneralityof thesechanges.Increasedheterogeneitymayhelpsurvivalnotonly atthelevelofindividualcells,butalsobyallowingtheformation ofcooperatinginter-cellularnetworksofcancercells[10,11].This cooperative,paracrinecross-regulation maychangetoaselfish, autocrinedevelopmentlater[12,13].

Inmanygeneralaspects,thedevelopmentofcancercellsresem- blestothatresultinginchangesofcellularphenotypese.g.during embryogenesis.Majorstepsoftheepithelial-mesenchymaltransi- tion(whereepithelialcellsloseboththeirapical/basalpolarityand originalcellularcontacts,gaintheabilitytotransversetheextra- cellularmatrix,andultimatelycontributetotissuesotherthanthe originalepithelialsheet) correspondwelltothemajorstages of metastasisformation[14,15].

Herewearguethatmalignanttransformationisessentiallya two-phaseprocess.Weproposethatthefirstphaseofmalignant transformationischaracterizedbyanincreaseofplasticityinthe protein-proteininteraction,signalingandothernetworksoftrans- formedcells,whichisfollowedbydecreaseofnetworkplasticity (Fig.1),wherenetworkplasticity(orinotherwordsnetworkflex- ibility)isrelatedtothedegreesoffreedomofnetworknodes[16].

Theinitialstagemaycorrespondto“clonalexpansion”,andthe appearanceoftumorinitiatingcells.Thelatestagemayrepresent eitherlate-stageprimarytumorcells, ormetastaticcells, which alreadysettledintheirnoveltissueenvironment.

Cancerstemcells[17]canpossessbothtypesoftheabovedual- ity.Cancer stem cellscan displaya dormant phenotype, which isnotrapidlyproliferating,andhasamorerigidstructureofits protein-proteininteraction,signalingandothernetworksthanthat ofrapidlyproliferatingearlystagetumorcells.Importantly,cancer stemcellsmayalsopossessarapidlyproliferatingphenotype[17], whichmayhaveahighlyplasticnetworkstructure.Therefore,can- cerstemcellsarenotdiscriminatedbytheplasticityoftheiractual networkstructures(calledasstructuralplasticity[16]),butbytheir especiallyhighabilitytomodulatetheplasticityoftheirnetworks (calledasdynamic plasticity[16])accordingtotheneedsofthe environment.Itisimportanttonotethatthespeciallyhighability ofcancerstemcellstomodulatetheplasticityoftheirnetworksisin accordancewiththeoriginalcancerstemcelldefinitionoftumor initiationafterserialdilutions[17].Ahighlyincreasedabilityof plasticitymodulation(whichresultsinanincreasedlevelofevol- vability)mayprovetobeamajordiscriminatoryhallmarkofcancer stemcells.Importantly,thisincreasedplasticitymodulationability maybeakeyreasonwhyanti-cancertherapiesofteninducecancer stemcellsinsteadofkillingortransformingthem.

Therearemanysignsoftheinitialincreaseofsystemplasticity duringcancerdevelopment,suchastheincreasedheterogeneity, noiseandentropymentionedbefore.Tumorinitiatingcellsshowed alargerplasticityalsoatthelevelofphysicaldeformability[18,19].

However,at latestage carcinogenesisof theprimary tumor,or whentumorcellsalreadyestablishedmetastasesandwereincor- poratedtoa more stabletissue environment,thesystems-level plasticityofcancercellsmaydecreaseagain.

Thecancer-specific,metastablestates,whichweretermedas

“cancer attractors” by Stuart Kauffman in 1971 [3,20] may be especiallytypicaltotheselaterstagesofcancerdevelopment.Addi- tionally,earlystagesofcancerdevelopmentmaybecharacterized

bynumerous“shallow”cancerattractorsdevelopingamoreplastic structuralnetworkofthecellresidingintransitonthisrelatively smoothstatespaceenvironment,whilelatestagesoftumordevel- opmentmayinvolvefewerbut“deeper”cancerattractors,where thecancercellbecomesstabilizedinthismoreroughstatespace environment.Thedualchangedescribedabovecorrespondswell tovariousstepsinthetransitiontocancerattractors,sincecancer cellsshouldfirstcrossabarrierinthe(epigenetic)fitnessland- scape,whichmightbeloweredbymutationsorepigeneticchanges [3],butstillrequiresatransientdestabilizationofthetransforming cell,whichleadstoamoreplasticphenotypewithallthepheno- typiccharacteristicsdescribedbefore.Thephenotypeofthealready established,late-stagecancercellsisstillmoreplasticandimma- turethanthatofnormalcells,butmayoftenbemorerigidthanthe phenotypeofthecellsintheintermediatestagesofcarcinogenesis (Fig.1).

Suchabiphasicchangeresemblestothatofcelldifferentiation processes,where aninitialincreaseof entropyof chromosomal orderandco-regulatedgeneexpressionpatternisfollowedbya later decrease[21].Ananalogous setofeventshappens in cel- lularreprogramming, wheresingle-cellstudiesrevealedthatan earlystage,veryheterogeneous,stochasticphaseisfollowedbya latephase,whichisprogrammedbyahierarchicalsetoftranscrip- tionfactors[22].Therecentlydiscoveredsuper-enhancers[23,24]

maycharacterize this second,consolidated phase of phenotype rearrangement.Importantly,amoreorderedsystemisgenerally lesscontrollablethanadisorderedone[25],whichwarnsthat(A) therapeuticinterventionsofearlystageofcarcinogenesisaremore efficientthanthoseagainstlate-stagetumors;(B)late-stagetumors shouldbeattackedbyafullydifferentstrategy thanearly-stage tumorspreferringindirecttargetshavingasmallercentralityin molecularnetworks,whichcauselesssideeffectsandtoxicityin thesemorerigid,late-stagecancer-specificnetworks/cellularsys- tems,seeFig.1and[26].

2. Networksegmentsparticipatinginadaptiveprocesses

The cancer development process is increasingly described asa systems-level,network phenomenon[27,28].Applyingthis descriptiontothecancerdevelopmentstagesdescribedabove,in thissectionwesummarizetheadaptationoptionsofnetworkstruc- turesingeneral.InSection3,wewilldescribethecancer-specific networkadaptationevents.

Adaptationofnetworksisoftendescribedas“networkevolu- tion”,where thetermreferstochangesinthenetwork contact structure(e.g.changesof parameterslikenetworkconnectivity, edgeweights,diameter,centrality,motifsormodules[29,30]).The identificationofthesechangeshasapredictivepotentialbothin retrospectandaboutfuturedevelopmentofthecomplexsystem representedbythenetwork.Networkevolutionmayfollowdif- ferenttimescalesvaryingfrommicrosecondstodecadesormore [31–33].Thus theassessment ofmolecularnetwork changes in theprogressionofcancerrequiresaverycarefulselectionoftime- framesbothinclinicalsamplingandinnetworkanalysis.

Networkdynamicsextendstheframeofnetworkevolutionto therefinedchanges of network nodes(e.g. individualproteins) whentransmittingsignals,orparticipatingintheircellularfunc- tionrequiring aconcertedaction ofmultipleproteins. Network dynamicsisstronglyrelatedtotheunderlyingnetworktopology.

Transitionstoanewstate,asitwasseenintumordevelopment [34],havekeyimportanceinnetworkdynamics.

Hubs(i.e.nodeswithmuchmoreneighborsthantheaverage) arekeydeterminantsoflocalnetworktopology[35].Akeyexample ofthesehighlyconnectedhubsisthep53protein.Thep53tumor suppressorisindeedakeyregulatorofcancer-relatedmolecular

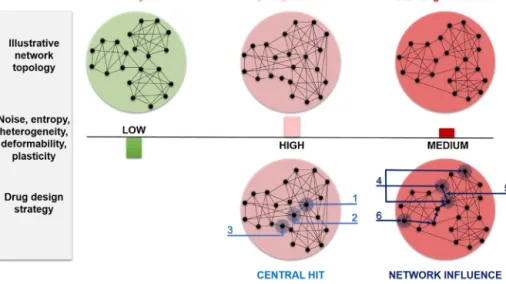

Fig.1.Developmentofcancerasalearningprocessofincreasingandthendecreasingplasticityatthesystems-leveldeterminesthemostappropriatedrugtargetingstrategy.

Thefigureillustratesthemajorhypothesisofthecurrentreviewshowingthatthetransitionofcellstoacancerattractorduringmalignanttransformationisessentially atwo-phaseprocess.Weproposethatinthistransformationaninitialincreaseofsystemplasticityisfollowedbyalate-stagedecreaseofplasticity.Plastic,earlystage systemsofcancerdevelopmentarecharacterizedbyahigherlevelnoise,entropyandphysicaldeformability.Theplastic→rigidtransitionofnetworkstructureduring cancerdevelopmentinvokesaratherdifferenttargetingstrategyinearlyandlatephaseofcarcinogenesis.Whileattheearlyphaseofcancerdevelopmenthittingofcentral nodes(suchashubs,markedas“1”;inter-modularbridges,markedas“2”;orbottlenecks,markedas“3”)beinginthecross-roadsofregulatoryprocessesmaybeawinning strategy,atlaterstagesofcarcinogenesisthemoreindirectmeansofnetworkinfluencestrategy,suchasthemulti-target(markedas“4”),edgetic(markedas“5”)orallo- networkdrugs(markedas“6”)[26,79,80]shouldbeused.Importantly,heterogeneouscancercellpopulations[6,92]mayharborearly-andlate-stagetumorcellsatthesame time.Moreover,cancerstemcells[16]mayhavetheabilitytochangetheir“plasticityphenotype”fromthatofearly-tolate-stagetumorcellsandviceversa.Therefore, multi-target,combinatorialorsequentialtherapiesusingbothcentralhit-andnetworkinfluence-typedrugsmayprovideanevenmoreusefulanti-cancertherapeutic modalitythanpreviouslythought.

networks[36–38].Manydifferentpathwaysmayconvergeonhubs, whichareoftenevolutionaryconservedproteins[39].Reversely,a huboftenactsasadistributorofperturbations.Networkmotifsare repeatedlocalpatternsofnetworktopologytypicallyconsistingof 3to6nodes.Negativefeedbackloopsandfeed-forwardloopsare significantmotifsinadaptation[40,41].

Networkmodulesaregroupsofnodesconnectedmoredensely to each other than to the rest of the network. In molecular networksaspatialortemporalmoduleoftenmeansafunctional unit [42]. Altered modularity was shown as a predictive mea- sure in breast cancer prognosis [43]. Most modules of cellular networkshaveahighoverlapwitheach other[44,45].Modules of theyeast protein–protein interaction network are becoming morecondensedanddisplayingsmalleroverlapsuponstress[46].

In extremecases stress mayresult in thedisintegration ofthe networkleadingtothedeathoftheorganism,whichmaybean importantpartofthenetwork-levelmechanismofactionofseveral anti-cancerdrugs.

Modules may segregatenetwork segments, which are more plasticand/ormorerigid.Whilerigidnetworksegmentspreserve theresultofapastadaptiveprocessoftendisplayinganoptimized function,flexiblenetworksegmentsarecapableofplasticadapta- tiontopresentorfuturechallengesoftheenvironment.Whilerigid networksegmentsareableforfastsignaltransmissionwithouta largedissipation,plasticnetworksegmentshaveaslowersignal transmissionandalargerdissipation[16,26,47].

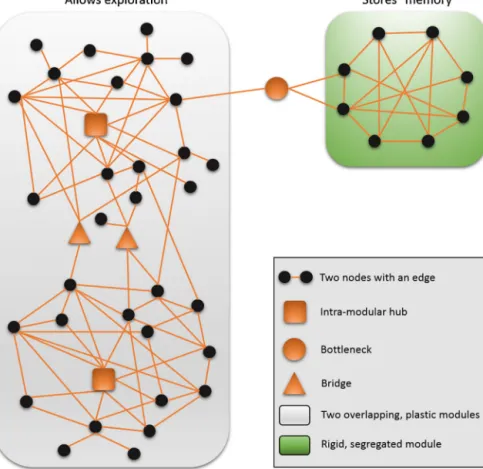

Bridgesarenode-pairsconnectingmodules,andabottleneckis akeyinter-modularnode.Networkperturbationshavetopropa- gatethroughthesenodes,thereforebridgesandbottlenecksare important points of regulation and adaptation [48,49].The so- calledcreativenodes[50]arejoiningmultiplemodulesinahighly dynamicfashion.Creativenodesconnectfunctionallydistinctmod- ules.Therefore,theabundanceoftheseexceptionallyunpredictable nodesmaybeakeyregulatorof“adaptation-speed”andrelatedsys- templasticityandevolvability.Fig.2illustratesthemostimportant structuralelementsofnetworkadaptation.

3. Cancer-specificpropertiesofmolecularnetworks

Afterthe descriptionof key network segmentsparticipating inadaptiveprocessesingeneral,herewesummarizethecurrent knowledgeonthemostimportantchangesofmolecularnetworks incancerdevelopment.Table1highlightsafewproteinsplayinga keyroleincancer-relatedmolecularnetworks.

Proteinstructure networkshave nodesof proteinsasamino acids,wheretheedgeweightdependsonthedistanceoftwoneigh- boring aminoacids inthe3D structure oftheprotein.Detailed studies on the network representation of cancer-specific pro- teinsandtheirmutationsaremissing.However,recurrentfindings showedthatintrinsicallydisorderedproteinsplayanimportant roleincancer-specificcellularevents[51–53].Additionally,cancer- related proteinshave smaller, more planar, more charged and less hydrophobic bindinginterfaces than other proteins, which mayindicatealowaffinityandhighspecificityofcancer-related interactions [54]. An increased “conformational noise” in can- cerrepresentedbyintrinsically disorderedproteinsand bylow affinityinteractionswouldbeinagreementwiththemoreplas- tic network structure of tumor initiating cells. Our hypothesis would predictadecreased expressionofdisorderedproteinsor proteinswithlow affinityinteractions inthelate-phaseofcan- cer development (i.e. in late stage primary tumors, or when metastaticcellsalreadysettledinthenoveltissueenvironment) asopposed totheearlyphasesof “clonalexpansion”,orcancer stemcellformation,wheretheexpressionoftheseproteinsmay behigher.

Protein–proteininteractionnetworks(interactomes)havethe individualproteins(ortheirdomains)asnodes,and theirphys- ical interactions as edges.Cancer-specific interactomes may be constructed by taking into account protein abundances, or (as a first approximation)incorporating mRNAexpression patterns [48,55,56].Amicroarraygeneprofilingstudyshowedthatgenes with elevated expression are coding well-connected proteins, while suppressed genes code less connected proteins in lung

Fig.2.Examplesofkeystructuralsegmentsparticipatinginnetworkadaptation.Thefigureillustratesafewkeystructuralnetworksegments,whichoftenplayakeyrolein theadaptationofcomplexsystems.Intra-modularhubsarehighlyconnected,centralnodescollectinganddistributingnetworkperturbations.Bridgesandbottlenecksare crucialregulatorsofinformationflowbetweennetworkmodules.Networkmodulesoftenfunctionalunitsandmaydisplayarigidorflexiblestructure.Whiletheformerhas beenoptimizedtoacertainfunction,andmayserveasa“memory”ofthenetworkpreservingtheresultofsuccessfuladaptationtopastevents,thelattermayprovidethe plasticitypromotingadaptiveprocessesinthepresentorfuture.

squamouscancer[57].Interactome-basedstudiesindicated that proteinswithcancer-specificmutationsarehubswithatendency toforma“rich-club”,i.e.beingconnectedwitheachother[58], andarelocatedinthecenterofmodulesorcreatebridgesbetween them[59].Inter-modularhubs,suchasIRS1orBRAF,haveapartic- ularlyimportantroleinoncogenesis[43].Cancer-relatedproteins tendtoformtransientinteractionsandusuallyinvolvedinmul- tiple pathways[54]. Dynamical rearrangements of interactome segmentsmaycontributetothechangesinplasticityduringcancer development.Gene-expressionenrichedprotein–proteininterac- tionnetworks of 6 cancertypes showedan increased network entropy,ifcomparedtointeractomesofhealthycells[8].Increased network-entropymaybeanimportantingredientoftheincreased plasticityofmalignantcells, andmaysignificantlycontributeto theincreasedrobustnessagainststressandotherenvironmental stimuli.

Theautonomyofthecancercellisbasedmainlyonthechanges initssignalingnetwork,formedbyinterconnectedsignalingpath- waysincludingitsgeneregulatorynetwork[60].Changesinthe expressionlevelof signalingproteinsin cancercellsmaycause theactivationofmajorcancer-relatedpathways,andcanrewire thewholesignalingnetwork,asitwasshowninthecaseofthe epidermalgrowthfactorreceptor(ERBB1)signalingnetwork[61].

Cross-talksbetweentheindividualsignalingpathwaysareableto createahighnumberofnewinput-outputcombinationsincreas- ingtheplasticityofthesignalingnetwork[2].Earlier,wefounda significantchangeintheexpressionlevelofspecificcross-talking proteinsinhepatocellularcarcinomaleadingtoahighlydifferent, malignantnetworkofsignalingpathways[62].Theup-regulation andcross-talksofRAS-ERKandPI3K-mTORC1pathwaysplayakey roleintheprogressionofseveraltumortypes[63].Theregulationof signalingcross-talkshighlydependsonthespatialorganizationof

Table1

Networkdrugtargetoptions.

Molecularnetworktype Possibledrugtargets Cancer-specificnetworkpropertiesofpossibledrugtargets References

Protein–proteininteractionnetwork p53,CDK6 Hubinactivation,bottleneckdysfunction [36,49]

Signalingnetwork ERBB1

PDGFR,TGFBR

Edgeticperturbationofreceptortyrosinekinasepathway Cross-talksofdifferentpathwaysduring

epithelial-mesenchymaltransition

[61]

[95]

Geneticinteractionnetwork MYC,NES,MMP2,FOS,TNC Hubover-activation,hub-drivingnodeunder-activation [96]

Chromatinnetwork BRD4 Super-enhancerparticipatinghub [23]

Metabolicnetwork Fumaratehydratase,Succinate dehydrogenase,

PKM2

TargetingtheWarburgeffect, Increasedmetabolicflux

[97]

[98]

thecellinvolvingdifferencesinmolecularcrowding[64],scaffold proteins[65],proteintranslocation[66]ormembraneassociation [67].Increasednetworkentropywasfoundinthesignalingnet- workofthemetastasizingphenotypeofbreastcancer,ifcompared tonon-metastasizing cells [7]. Thismay indicate theincreased plasticityofcancer-specificsignalingintheearlyphasesoftumor development.Our recentstudiesshowedthatincreasedplastic- ityofsignalingnetworkscharacterizestheinitialstagesoftumor development(suchasadenomas)betterthanlaterstagesofmalig- nanttransformation (suchascarcinomas;Dezs ˝oMódos,Katalin Lenti,TamásKorcsmárosandPéterCsermely,inpreparation).

Transcriptionalregulationis oftenexecutedbyahierarchical cascadeoftranscriptionalfactors.Therecentlydiscoveredsuper- enhancers[23,24]showedthatmastertranscriptionfactorsmay oftenestablishacancer-specificsuper-enhancer locus.Whether theorganizationofthesesuper-enhancerregionsrepresentsalate- phaseofcarcinogenesis,andisprecededbyaveryheterogeneous, stochasticearlyphase,likethatincellreprogramming[22],isan openquestionoffuturestudies.

Chromatinnetworksareformedbyconnectionsbetweendis- tantDNA-segments,andcanbeusedfortheexplanationofthe chromosomal alterations in cancer [68]. The overexpression of theprostatecanceroncogenictranscriptionfactor, ERGinduced aprofoundeffectonchromatinnetworkconfiguration[69].Fur- therstudiesareneededtoassessthecancer-specificalterationsof transcription-relatedchromatinnetworks,suchasthatdescribing theconnectionpatternestablishedbytheactiveRNA-polymerase II-complex[70].

RegulationormutationsofmicroRNAsplayacrucialroleinthe regulationofcancer-specificgeneexpression[71].MicroRNAscan functioneitherastumorsuppressors,suchasthelet-7familymem- berstargetingtheRASsignalingpathwayinbreastcancer[72],or asoncogenes,likethemiR-155targetingkeybreastcancergenes, suchas FOXO3A or RHOA[73].The analyses of cancer-specific microRNA networksshowedmore disjointedsubnetworks than innormaltissues[74].Disjointmodulesdecreasetheinterdepen- denceofmodularchanges,andalsoserveasanadaptiveresponse instress[46].Disjointmodulesconferagreaterplasticitytothe wholesystem.

Metabolicnetworksconsistofmajormetabolitesasnodescon- nectedbyspecificenzymatic reactionsconvertingthemtoeach other[75].Globalchangesinmetabolicnetworkscontributetothe Warburg-effect,andaredrivenbykeyenzymessuchasthePKM2 isoenzymeofpyruvatekinase[76,77].

Thestage-specificchangesof molecularnetworksin tumori- genesis are still largely unexplored, because we usually have detailedsystems-levelnetworkdataonlyonthetwoendpoints, i.e.thehealthytissueandthedevelopedlatetumors.Therefore, theassessmentofconsecutivechangesinnetworkstructureand dynamicsduringintermediate,consecutivestepsofmalignantcell and metastasisformation are key stepsof future systems-level analysisofcancerdevelopment.Networkanalysisofcancerstem cellswillprovideaspecialunderstandingofbothplasticitymodu- lationandevolvabilityatthesystems-level.

4. Network-relatedanti-cancertherapies

Itisagrowingchallengetoidentifynewdrugtargetsandeffi- cient combination of drugs in order todesign newanti-cancer therapieswithlesstoxicity,side-effectsandresistancedevelop- ment. As we have shown in the preceding section molecular networks at various levels greatly improved our systems-level understandingoftumorinitiationandprogression[26–28,78].

Recentlyadualnetworkstrategy,thecentralhitstrategyand thenetworkinfluence strategy,wasdescribed totargetvarious

diseases [26].In cancerboth strategiesmay beused.Using the centralhitstrategy ouraimis todamage thenetwork integrity ofthemalignantcellinaselectivemanner.Thismaybethemost importantstrategytoattacktumorinitiatingcellsattheirfirststage ofdevelopment(e.g.earlystagesofmalignanttransformationof metastasisformation).Usingthenetwork influencestrategywe wouldliketoshiftbackthemalfunctioningnetworktoitsnormal state.Thismaybethemostimportantwaytoshiftbacktumorcells fromtheircancerattractorsreachedinlatestagesoftheirdevel- opment(e.g.latestageprimarytumorsorafterthemetastaticcells settledtotheirnewtissueenvironment).Thecentralhitstrategy isappliedagainstapopulationofhighlydestabilizedcellshavinga veryplasticnetworkstructure.Efficienttargetingofthesesystems requiresthetargetingoftheircentralnodes/edges.Incontrast,the networkinfluencestrategyisappliedtocells,whichhaveamuch morerigidnetworkstructurethanthenetworksofhighlyundiffer- entiatedordedifferentiatedcells.Targetingthecentralnodes/edges ofsystemshavingalowplasticitymayeasily‘over-saturate’the systemcausingside-effectsandtoxicity.Therefore,thenetwork influence strategy oftenneedsanindirect approach,where e.g.

neighborsoftherealtargetaretargeted(allo-networkdrugs[79]).

In another indirectapproach of thenetwork influence strategy multipletargetsaretargetedatthesametime‘mildly’(usingmulti- targetdrugs[80]),andtheirindirectand/orsuperposingeffectslead tothereconfigurationofdiseasednetworkstatebacktonormal.

Thecentralhitstrategyoftenusesthekeycentralpositionof inter-modularhubs.Thesecentralnodesareoftenimportantonco- genesservingastargetsindrugdevelopment[43].Similarly,in signaling networks protein or microRNA hubs [48,57,58,81,82], inter-modular positions of cross-talks [83], bottlenecks [84] as wellasmulti-pathwayproteinsofferimportanttargetcandidates [43,62]ascentralhits.

However,thecentralhitstrategymayoftenattacknodes,which aresocentralthattheirinhibitiondamageskeyfunctionsofhealthy cells.Asanexample,mTOR,themammaliantargetofrapamycin isanimportantmulti-pathwayprotein,whichmutatesinmostof thetumorsandthuscauseshyper-activephenotype[85].Because of the super-central position of mTOR, edgetic drugs targeting singlemTORinteractionshaveamuchmoreselectiveeffect[86]

thantargetingallmTORinteractionsbyconventionaldrugs[87].

Anotherexampleofedgeticanti-cancertherapiesistheinhibition ofp53/MDM2connectionbynutlins,which liberatethetumor- suppressoreffectofp53fromMDM2-inducedinhibition[88].

The network influence strategy often implies multi-target attacks[80].Theseattacksmayallowthesimultaneoustargeting oftwoormoreperipheralnodesinsteadoftargetingasingle,cen- tralnode[25].Such combinatorialormulti-targettherapiescan beidentifiedusinginteractomes,signalingormetabolicnetworks [89,90]and ledtothe design a simultaneoustargeting therapy e.g.incolorectalcancer[91].Thesystematicdevelopmentofallo- networkdrugs[79]actingattheneighborhoodofrealtargetsand specifically transmitting theirsignals to them requires a more detailedknowledgeofbothindirecttargetingandthemolecular detailsofallostericaction,andthereforeremainsandmajorchal- lengeoffuturestudies.

5. Networkadaptationinvariousstagesofcancer developmentasakeyaspectofanti-cancertherapies

Hereweproposethatthelargestructuralchangesofmolecu- larnetworksduringcancerdevelopmentrequirearatherdifferent targetingstrategyinearlyandlatephaseofcarcinogenesis(Fig.1).

Whileattheearlyphaseofcancerdevelopmenthittingofcentral nodesinvariousmolecularnetworks(suchasinter-modularhubs beinginthecross-roadsofregulatoryprocesses)maybecomea

winningstrategy,theverysamepharmacologicalinterventionmay becomeuselessatalaterstageofcarcinogenesis,wheretheprimary tumorwasalreadyestablished,orthemetastasizedcellshavebeen settledin theirnewtissueenvironment.Theselate-stagetumor cellsshouldbeattackedbythemoreindirectmeansofnetwork influencestrategy,suchasbyedgetic,multi-target,orallo-network drugs[26,79,80].

TheanalysisofRajapakseetal.[25]offersimportantcluesontar- getingmolecularnetworksduringcancerdevelopment.Referring tothegeneralobservationthatsymmetricalnetworksaremore uncontrollable,theyhypothesizethatthehighlyheterogeneous, highly plastic, intermediate state of tumor-initiating cells right beforeoratattainingtheirmetastaticpotentialisthemostdifficult toattackbywell-targetedexternalinputs.Thisisthephase,where onlythecentral-hitstrategymaybeapplied.However,atlatestage primaryormetastatictumors,wheretheunderlyingnetworkstruc- turesbecamemoreasymmetricagain(Dezs ˝oMódos,KatalinLenti, TamásKorcsmáros andPéterCsermely,inpreparation)onlythe indirecteffectsofthenetworkinfluencestrategymaybesuccessful.

Veryimportantly,cancersoftenharborcancerstemcells,which maybeinducedbyconventionalanti-cancertherapies,themselves [16].These stemcell-liketumor cellsubpopulationspossess an extraordinarilyhighabilitytochangetheirplasticity.Whencan- cerstemcellsacquireamoredormantstate,theymaychangetheir networksfromamoreplastictoamorerigidstructure.Onthecon- trary,cancerstemcellsmayhaveatransitionfromamorerigidtoa moreplasticnetworkstructure,iftheyformearlytumorprogenitor cells.Thislargelevelofdynamicplasticitymaybeamajorreason ofthedevelopmentofdrugresistanceinmanycancercases.

Thepresenceofhighlyheterogeneouscellpopulations(includ- ingvariousformsofcancerstemcells)inacancerpatient,aswell astheextremeheterogeneityofpatientsubtypes[6,92]allgivea particularimportanceofsequentialmulti-targettherapies,where multipledrug treatments are given in a particular order using a well-designedtemporal pattern of consecutivetreatments. In agreementwithKitano[1]andmanykeyresultsinthefield(e.g.

whenepidermalgrowthfactorreceptorinhibitorssensitizedcan- cercellstosubsequentDNA-damagebyunmaskinganapoptotic pathwayinbreastcancerseetheworkof[93]andthereviewof HuangandKauffmaninthisissue)westronglybelievethatsequen- tialmulti-targettherapywillbethemajormodeofinterventionin cancertherapiesofthefuture.

6. Conclusionsandperspectives

Inconclusion,inthisreviewweproposedthatmalignanttrans- formation is a two-phase process, where an initialincrease of systemplasticityis followed bya decreaseof plasticity at late stagesofcarcinogenesisofprimarytumorcellsorofmetastaticcells alreadysettledintheirnoveltissueenvironment.Theincreased systems-levelplasticityofcancerinitiatingcellsischaracterized byanincreased

•levelofstochasticprocesses(noise);

•networkentropy;

•“conformationalnoise”representedbyintrinsicallydisordered proteinsandbylowaffinityinteractions;

•phenotypicplasticity;

•cellheterogeneity;

•physicaldeformabilityand

•dissociationofnetworkmodules(Fig.1).

Ourhypothesiswouldpredictadecreaseinalltheaboveparam- etersinthelate-phasesofcancerdevelopmentasopposedtothe earlyphases described above. In late phase carcinogenesis the

increaseofsystemrigiditymaybeaccompaniedbyanincreased hierarchyofregulatoryprocesses.

Thelargestructuralchangesofmolecularnetworksduringcan- cerdevelopmentrequirea ratherdifferenttargetingstrategy in earlyandlatephaseofcarcinogenesis.Importantly,amoreordered systemisgenerallylesscontrollablethana disorderedone[25], whichwarnsthat(A)therapeuticinterventionsoftheearly,more plasticstageofcarcinogenesisaremoreefficientthanthoseagainst late-stage tumors;(B) late-stage tumors shouldbe attackedby anentirelydifferentstrategythanearly-stagetumors,seeFig.1 and[26].Besidesothertherapeuticmodalities (suchassurgery, radiotherapyetc.)attheearlyphaseofcancerdevelopmenthitting ofcentralnodesofcancerousmolecularnetworks(suchasinter- modularhubsbeinginthecross-roadsofregulatoryprocesses)may becomeawinningstrategykillingtheveryheterogeneouscancer cellpopulation.However,centralhit-typepharmacologicalinter- ventionsmaybecomeuselessatalaterstageofcarcinogenesis.Late stageprimarytumorsorthealreadymetastasizedcellsintheirnew tissueenvironmentshouldbeattackedbythemoreindirectmeans ofnetworkinfluencestrategy,suchasbyedgetic,multi-target,or allo-networkdrugs seeFig.1and[26,79,80],since herenotthe eradicationofalargeheterogeneityoftumorcells,buttheshift ofthemalignantcellularnetworktoalessmalignantstateisthe desiredaction.

Regretfully,manyinvitrotestsystemsofanti-cancerdrugcan- didatesresembletotheplasticcellularsystemsofearlystagecancer development,whilediseaseisusuallydetectedinpatients,when itreachedthelatephaseofdevelopment[94].Theapplicationof earlystage-optimizedanti-cancerdrugstolate-stagepatientsmay beareasonofmanyfailuresinanti-cancertherapies.Thissituation underliestheimportanceofsystems-levelstudiesofcancercell developmentandthenetworkanalysisofthedataobtained.

Importantly,theinitialincreaseandlater decreaseofsystem plasticityduringcancerdevelopmentmayappearbothatthelevel ofthenetworkofindividualcellsandatthelevelofthenetworkof cellpopulations.Heterogeneouscancercellpopulationsmayhar- borearly-andlate-stagetumorcellsatthesametime.Moreover, cancerstemcellsmayhavetheabilitytochangetheir“plasticity phenotype”fromthatofearly-tolate-stagetumorcellsandvice versa.Therefore,multi-target,combinatorialorsequentialthera- piesusingbothcentralhit-andnetworkinfluence-typedrugsmay provideanevenmoreusefulanti-cancertherapeuticmodalitythan previouslythought.

Conflictofinterest

Authorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

Acknowledgements

Work in theauthors’ laboratorywas supported byresearch grantsfromtheHungarianNationalScienceFoundation(OTKA- K83314), from the EU (TÁMOP-4.2.2/B-10/1-2010-0013) and a JánosBolyaiScholarshiptoTK.

References

[1]KitanoH.Cancerasarobustsystem:implicationsforanticancertherapy.Nature ReviewsCancer2004;4:227–35.

[2]KitanoH.Biologicalrobustness.NatureReviewsGenetics2004;5:826–37.

[3]HuangS,ErnbergI,KauffmanS.Cancerattractors:asystemsviewoftumors fromagenenetworkdynamicsanddevelopmentalperspective.Seminarsin Cell&DevelopmentalBiology2009;20:869–76.

[4]PujadasE,FeinbergAP.Regulatednoiseintheepigeneticlandscapeofdevel- opmentanddisease.Cell2012;148:1123–31.

[5]GreavesM,MaleyCC.Clonalevolutionincancer.Nature2012;481:306–13.

[6]MarusykA,AlmendroV,PolyakK.Intra-tumourheterogeneity:alookingglass forcancer?NatureReviewsCancer2012;12:323–34.

[7]TeschendorffAE,SeveriniS.Increasedentropyofsignaltransductioninthe cancermetastasisphenotype.BMCSystemsBiology2010;4:104–16.

[8]WestJ,BianconiG,SeveriniS,TeschendorffAE.Differentialnetworkentropy revealscancersystemhallmarks.ScientificReports2012;2:802–9.

[9]Breitkreutz D,HlatkyL,RietmanE,TuszynskiJA.Molecularsignalingnet- workcomplexityiscorrelatedwithcancerpatientsurvivability.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012;109:9209–12.

[10]AxelrodR,AxelrodDE,PientaKJ.Evolutionofcooperationamongtumorcells.

ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica 2006;103:13474–9.

[11]BonaviaR,IndaMM,CaveneeWK,FurnariFB.Heterogeneitymaintenancein glioblastoma:asocialnetwork.CancerResearch2011;71:4055–60.

[12]CreixellP,SchoofEM,ErlerJT,LindingR.Navigatingcancernetworkattractors fortumor-specifictherapy.NatureBiotechnology2012;30:842–8.

[13]WuY,GarmireLX,FanR.Inter-cellularsignalingnetworkrevealsamechanistic transitionintumormicroenvironment.IntegrativeBiology2012;4:1478–86.

[14]ThieryJP.Epithelial–mesenchymaltransitionsintumourprogression.Nature ReviewsCancer2002;2:442–54.

[15]KalluriR,WeinbergRA.Thebasicsofepithelial–mesenchymaltransition.Jour- nalofClinicalInvestigation2009;119:1420–8.

[16]TangDG.Understandingcancerstemcellheterogeneityandplasticity.Cell Research2012;22:457–72.

[17]GáspárME,CsermelyP.Rigidityandflexibilityofbiologicalnetworks.Briefings inFunctionalGenomics2012;11:443–56.

[18]GuckJ,SchinkingerS,LincolnB,WottawahF,EbertS,RomeykeM,etal.Optical deformabilityasaninherentcellmarkerfortestingmalignanttransformation andmetastaticcompetence.BiophysicalJournal2005;88:3689–98.

[19]ZhangW,KaiK,ChoiDS,IwamotoT,NguyenYH,WongH,etal.Microfluidics separationrevealsthestem-cell-likedeformabilityoftumor-initiatingcells.

ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica 2012;109:18707–12.

[20]KauffmanS.Differentiationofmalignanttobenigncells.JournalofTheoretical Biology1971;31:429–51.

[21]RajapakseI,PerlmanMD,ScalzoD,KooperbergC,GroudineM,KosakST.The emergenceoflineage-specificchromosomaltopologiesfromcoordinategene regulation.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnited StatesofAmerica2009;106:6679–84.

[22]BuganimY,FaddahDA,ChengAW,ItskovichE,MarkoulakiS,GanzK,etal.

Single-cellexpressionanalysesduringcellularreprogrammingrevealanearly stochasticandalatehierarchicphase.Cell2012;150:1209–22.

[23]LovénJ,HokeHA,LinCY,LauA,OrlandoDA,VakocCR,etal.Selectiveinhi- bitionoftumoroncogenesbydisruptionofsuper-enhancers.Cell2013;153:

320–34.

[24]WhyteWA,OrlandoDA,HniszD,AbrahamBJ,LinCY,KageyMH,etal.Mas- tertranscriptionfactorsandmediatorestablishsuper-enhancersatkeycell identitygenes.Cell2013;153:307–19.

[25]RajapakseI,GroudineM,MesbahiM.Dynamicsandcontrolofstate-dependent networks for probinggenomic organization. Proceedings of theNational AcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica2011;108:17257–62.

[26]CsermelyP,KorcsmarosT,KissHJM,LondonG,NussinovR.Structureand dynamicsofmolecularnetworks:anovelparadigmofdrugdiscovery.Acom- prehensivereview.Pharmacology&Therapeutics2013;138:333–408.

[27]DulbeccoR.Cancerprogression:theultimatechallenge.InternationalJournal ofCancerSupplement1989;4:6–9.

[28]HornbergJJ,BruggemanFJ,WesterhoffHV,LankelmaJ.Cancer:asystemsbiol- ogydisease.BioSystems2006;83:81–90.

[29]Dorogovtsev S, Mendes J. Evolution of networks. Advances in Physics 2002;51:1079–187.

[30]HolmeP,SaramäkiJ.Temporalnetworks.PhysicsReports2012;519:97–125.

[31]PálC,PappB,LercherMJ.Anintegratedviewofproteinevolution.Nature ReviewsGenetics2006;7:337–48.

[32]PazosF,ValenciaA.Proteinco-evolution,co-adaptationandinteractions.EMBO Journal2008;27:2648–55.

[33]GelmanH,PlatkovM,GruebeleM.Rapidperturbationoffree-energyland- scapes:frominvitrotoinvivo.Chemistry2012;18:6420–7.

[34]DelsantoPP,RomanoA,ScalerandiM,PescarmonaGP.Analysisofa“phase transition”fromtumorgrowthtolatency.PhysicalReviewE2000;62:2547–54.

[35]BarabasiAL,AlbertR.Emergenceofscalinginrandomnetworks.Science 1999;286:509–12.

[36]Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 2000;408:307–10.

[37]WadeM,LiYC,WahlGM.MDM2,MDMXandp53inoncogenesisandcancer therapy.NatureReviewsCancer2012;13:83–96.

[38]SchwartzJM,TianK,RajendranR,DoddananjaiahM,Krstic-DemonacosM.

DynamicsofDNAdamageinducedbypathwaysofcancer.PLoSONE2013;8, inpress.

[39]FraserHB.Modularityandevolutionaryconstraintonproteins.NatureGenetics 2005;37:351–2.

[40]MiloR,Shen-OrrS,ItzkovitzS,KashtanN,ChklovskiiD,AlonU.Networkmotifs:

simplebuildingblocksofcomplexnetworks.Science2002;298:824–7.

[41]MaW,TrusinaA,El-SamadH,LimW,TangC.Definingnetworktopologiesthat canachievebiochemicaladaptation.Cell2009;138:760–73.

[42]SpirinV,MirnyL.Proteincomplexesandfunctionalmodulesinmolecular networks.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStates ofAmerica2003;100:12123–8.

[43]TaylorIW,LindingR,Warde-FarleyD,LiuY,PesquitaC,FariaD,etal.Dynamic modularityinproteininteractionnetworkspredictsbreastcanceroutcome.

NatureBiotechnology2009;27:199–204.

[44]HorvathS,ZhangB,CarlsonM,LuKV,ZhuS,FelcianoRM,etal.Analysisof oncogenicsignalingnetworksinglioblastomaidentifiesASPMasamolecular target.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesof America2006;103:17402–7.

[45]FurlongLI.Humandiseasesthroughthelensofnetworkbiology.Trendsin Genetics2012;29:150–9.

[46]MihalikÁ,CsermelyP.Heatshockpartiallydissociatestheoverlappingmodules oftheyeastprotein–proteininteractionnetwork:asystemslevelmodelof adaptation.PLoSComputationalBiology2011;7:e1002187.

[47]GyurkóMD,SotiC,StetakA,CsermelyP.Systemlevelmechanismsofadapta- tion,learning,memoryformationandevolvability:theroleofchaperoneand othernetworks.CurrentProtein&PeptideScience2013;14,inpress.

[48]JonssonPF,BatesPA.Globaltopologicalfeaturesofcancerproteinsinthe humaninteractome.Bioinformatics2006;22:2291–7.

[49]YuH,KimPM,SprecherE,TrifonovV,GersteinM.Theimportanceofbottle- necksinproteinnetworks:correlationwithgeneessentialityandexpression dynamics.PLoSComputationalBiology2007;3:e59.

[50]CsermelyP.Creativeelements:network-basedpredictionsofactivecentres inproteinsandcellularandsocialnetworks.TrendsinBiochemicalSciences 2008;33:569–76.

[51]IakouchevaLM,BrownCJ,LawsonJD,Obradovi ´cZ,DunkerAK.Intrinsicdisorder incell-signalingandcancer-associatedproteins.JournalofMolecularBiology 2002;323:573–84.

[52]UverskyVN,OldfieldCJ,MidicU,XieH,XueB,VuceticS,etal.Unfoldomics ofhuman diseases:linkingproteinintrinsic disorderwith diseases.BMC Genomics2009;10:S7.

[53]MahmoudabadiG,RajagopalanK,GetzenbergRH,HannenhalliS,RangarajanG, KulkarniP.Intrinsicallydisorderedproteinsandconformationalnoise:impli- cationsincancer.CellCycle2013;12:26–31.

[54]KarG,GursoyA,KeskinO.Humancancerprotein–proteininteractionnetwork:

astructuralperspective.PLoSComputationalBiology2009;5:e1000601.

[55]CoulombeB.Mappingthediseaseproteininteractome:towardamolecular medicineGPStoacceleratedrugandbiomarkerdiscovery.JournalofProteome Research2011;10:120–5.

[56]Sardiu ME,Washburn MP.Building protein–proteininteraction networks with proteomics and informatics tools. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011;286:23645–51.

[57]WachiS,YonedaK,WuR.Interactome-transcriptomeanalysisrevealsthehigh centralityofgenesdifferentiallyexpressedinlungcancertissues.Bioinformat- ics2005;21:4205–8.

[58]HaseT,TanakaH,SuzukiY,NakagawaS,KitanoH.Structureofproteininter- actionnetworksandtheirimplicationsondrugdesign.PLoSComputational Biology2009;5:e1000550.

[59]XiaJ,SunJ,JiaP,ZhaoZ.Docancerproteinsreallyinteractstronglyinthehuman proteinproteininteractionnetwork?ComputationalBiologyandChemistry 2011;35:121–5.

[60]LinC-C,ChenY-J,ChenC-Y,OyangY-J,JuanH-F,HuangH-C.Crosstalkbetween transcriptionfactorsandmicroRNAsinhumanproteininteractionnetwork.

BMCSystemsBiology2012;6:18–30.

[61]KlinkeDJ.Signaltransductionnetworksincancer:quantitativeparameters influencenetworktopology.CancerResearch2010;70:1773–82.

[62]KorcsmárosT,FarkasIJ,SzalayMS,RovóP,FazekasD,SpiróZ,etal.Uni- formlycuratedsignalingpathwaysrevealtissue-specificcross-talks,novel pathwaycomponents,anddrugtargetcandidates.Bioinformatics2010;26:

2042–50.

[63]MendozaMC,ErEE,BlenisJ.TheRas-ERKandPI3K-mTORpathways:cross-talk andcompensation.TrendsinBiochemicalSciences2011;36:320–8.

[64]LewitzkyM,SimisterPC,FellerSM.Beyond“furballs”and“dumplingsoups”- towardsamoleculararchitectureofsignalingcomplexesandnetworks.FEBS Letters2012;586:2740–50.

[65]Nussinov R, Ma B, Tsai C-J. A broadview of scaffolding suggests that scaffoldingproteinscanactivelycontrolregulationandsignalingofmultien- zymecomplexesthroughallostery.BiochimicaetBiophysicaActa2013;1834:

820–9.

[66]MuscoliniM,MontagniE,PalermoV,DiAgostinoS,GuW,Abdelmoula-Souissi S,etal.Thecancer-associatedK351Nmutationaffectstheubiquitinationand thetranslocationtomitochondriaofp53protein.JournalofBiologicalChem- istry2011;286:39693–702.

[67]PálfyM,ReményiA,KorcsmárosT.Endosomalcrosstalk:meetingpointsfor signalingpathways.TrendsinCellBiology2012;22:447–56.

[68]FudenbergG,GetzG,MeyersonM,MirnyLA.Highorderchromatinarchitecture shapesthelandscapeofchromosomalalterationsincancer.NatureBiotechnol- ogy2011;29:1109–13.

[69]RickmanDS,SoongTD,MossB,MosqueraJM,DlabalJ,TerryS,etal.Oncogene- mediatedalterationsinchromatinconformation.ProceedingsoftheNational AcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica2012;109:9083–8.

[70]SandhuKS,LiG,PohHM,QuekYL,SiaYY,PehSQ,etal.Large-scalefunc- tionalorganizationoflong-rangechromatininteractionnetworks.CellReports 2012;2:1207–19.

[71]CalinGA,CroceCM.MicroRNAsignaturesinhumancancers.NatureReviews Cancer2006;6:857–66.

[72]YuF,YaoH,ZhuP,ZhangX,PanQ,GongC,etal.Let-7regulatesselfrenewal andtumorigenicityofbreastcancercells.Cell2007;131:1109–23.