ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

NeuroImage: Clinical

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/ynicl

Enhanced subgenual cingulate response to altruistic decisions in remitted major depressive disorder

Erdem Pulcu

a, Roland Zahn

a,c, Jorge Moll

e, Paula D. Trotter

a, Emma J. Thomas

a, Gabriella Juhasz

a,d, J.F.William Deakin

a, Ian M. Anderson

a, Barbara J. Sahakian

b, Rebecca Elliott

a,*aNeuroscience & Psychiatry Unit, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, School of Medicine, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

bDepartment of Psychiatry, MRC Wellcome Trust Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

cDepartment of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, UK

dDepartment of Pharmacodynamics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary

eCognitive and Behavioural Neuroscience Unit, D’or Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

a rt i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 13 February 2014

Received in revised form 16 April 2014 Accepted 17 April 2014

Keywords:

Charitable donation Major depression Reward processing Subgenual anterior cingulate Striatum

a b s t r a c t

Background: Majordepressivedisorder(MDD)isassociatedwithfunctionalabnormalitiesinfronto-meso- limbicnetworkscontributingtodecision-making,affectiveandrewardprocessingimpairments.Suchfunc- tionaldisturbancesmayunderlieatendencyforenhancedaltruismdrivenbyempathy-basedguiltobserved insomepatients.However,despitetherelevanceofaltruisticdecisionstounderstandingvulnerability,as wellaseverydaypsychosocialfunctioning,inMDD,theirfunctionalneuroanatomyisunknown.

Methods:UsingacharitabledonationsexperimentwithfMRI,wecompared14medication-freeparticipants withfullyremittedMDDand15demographically-matchedcontrolparticipantswithoutMDD.

Results: Comparedwiththecontrolgroup,theremittedMDDgroupexhibitedenhancedBOLDresponse inaseptal/subgenualcingulatecortex(sgACC)regionforcharitabledonationrelativetoreceivingsimple rewardsandhigherstriatumactivationforbothcharitabledonationandsimplerewardrelativetoalowlevel baseline.Thegroupsdidnotdifferindemographics,frequencyofdonationsorresponsetimes,demonstrating onlyadifferenceinneuralarchitecture.

Conclusions: WeshowedthataltruisticdecisionsproberesidualsgACChypersensitivityinMDDevenaf- tersymptomsarefullyremitted.ThesgACChaspreviouslybeenshowntobeassociatedwithguiltwhich promotesaltruisticdecisions.Incontrast,thestriatumshowedcommonactivationtobothsimpleandal- truisticrewardsandcouldbeinvolvedintheso-called“warmglow” ofdonation.Enhancedneuralresponse inthedepressiongroup,inareaspreviouslylinkedtoaltruisticdecisions,supportsthehypothesisofapos- sibleassociationbetweenhyper-altruismanddepressionvulnerability,asshownbyrecentepidemiological studies.

c 2014PublishedbyElsevierInc.

ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).

1. Introduction

Charitabledonationbehaviourisauniqueformofhumanaltru- ismwhichchallengeskinselectiontheoriesofinterpersonalhelping behaviours(Hamilton,1963;Fosteretal.,2006).The“warmglowutil- itymodel” positsthatpeopleengageinhelpingbehavioursbecause theyaresociallyrewardingandpleasurable(Andreoni,1990).The avoidanceofanticipatedguiltmaybeanotherimportantmotivator ofaltruisticbehaviour(Eisenberg,2000;Tangneyetal.,2007).Major depressivedisorder(MDD)isassociatedwithelevatedlevelsofself- blamingmoralemotionssuchasshameandguilt(seereviews:Kimet

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: rebecca.elliott@manchester.ac.uk (R. Elliott).

al.,2011;Pulcuetal.,2013);particularlysurvivorguilt(O’Connoret al.,2000)whichpersistsintoremission(Greenetal.,2013).Ithasbeen suggestedthatempathy-basedguiltisassociatedwithhyper-altruism inMDD(O’Connoretal.,2012).Epidemiologicalstudiessupportthis viewandsuggestthathyper-altruistictendencies(e.g.makingdo- nationsexceeding$10

/

month)constituteavulnerabilityfactorfor thefirstonsetofMDD(Fujiwara,2009).Thissuggeststhatcharitable donation,perhapsactingasanindexofempathy-basedguilt,may representatraitmarkerforMDD.Apotentialneuronalbasisofthis effecthasnotbeeninvestigated.Previousneuroimagingstudiesofcharitabledonationbehaviour inhealthyparticipantssuggestedselectivelyenhancedresponseof septalandsubgenualcingulate(sgACC)regionsduringdecisionsto

2213-1582/ $- see front matter c2014 Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license ( http: //creativecommons.org /licenses /by-nc-nd / 3.0 /).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2014.04.010

makedonationsrelativetodecisionstoacceptsimplemonetaryre- wards(Molletal.,2006).Theseptalpartofthenucleusaccumbens (Harbaughetal.,2007;Hsuetal.,2008)andananteriorventralarea oftheventromedialfrontalcortex(Hareetal.,2010)havealsobeen associatedwithdonationdecisions.ThesgACCwasalsofoundtobe moreactiveinpeoplewithhigherempathicconcernwhiletheymade decisionstosacrificemoneytohelpothers(FeldmanHalletal.,2012).

TheauthorsofthesestudiesarguethatthesgACCmayplayacriti- calroleinprocessingprosocialandaffiliativeemotionsaswellas moraldecisions.ThesgACChasreproduciblybeenfoundto selec- tivelyrespondwhilepeopleexperienceguilt,whichmayrelatetoits involvementindonationdecisions(Zahnetal.,2009a,2009c;Green etal.,2012a,Basileetal.,2011a;Moreyetal.,2012).

Incontrasttotheselectiveinvolvementofseptalandsubgenual cingulateregionsinapreviousstudyofaltruisticdonationdecisions relativetoselfishrewards,activationinthelateralstriatumwascom- montobothaltruisticandsimplemonetaryrewarddecisions(Moll etal.,2006),consistentwiththecommonlyreportedroleofstriatal structuresinprocessingfinancial(andother)rewards(Diekhofetal., 2012).Striatalresponsewasalsoobservedmorestronglywhenpeo- plemadedonationsinthepresenceofasocialaudience,therefore receivingadditionalsocialrewardssuchasrecognitionandappraisal (Izumaetal.,2010).Thesestudiessuggestthatseptal

/

subgenualre-gionsdistinguishaltruisticdecisionsfromthosethatincreaseindi- viduals’ownfinancialresources,potentiallyreflectingguiltorother prosocialprocesses,whereasstriatalregionsrespondbothtooutcome ofaltruisticdecisionsandtosimplereceiptofmoney,potentiallyre- flectingreward-relatedresponse.

Awell-establishedclinicalliteraturesuggeststhatMDDisassoci- atedwithbothstructural(Drevetsetal.,1997;Drevetsetal.,1998; Botteronetal.,2002;DrevetsandSavitz,2008) andfunctionalim- pairmentsofthesgACCduringthesymptomaticphase(Mayberget al.,1997;Maybergetal.,2000;Maybergetal.,2005;Siegleetal.,2006; Lehmbecketal.,2008),withabnormalitiesinfunctionalconnectivity (Greiciusetal.,2007).Connectivityabnormalitiesextendwellintore- missionwhilepatientsareprocessingguilt(Greenetal.,2012b).Stud- iesalsosuggestfunctionalimpairmentsofrewardprocessingsystems, includingthestriatum,evenwhensymptomsfullyremit(Tremblay etal.,2005;Schlaepferetal.,2008;Knutsonetal.,2008;Esheland Roiser,2010).Thesepreviousfunctionalneuroimagingstudieshave shownenhancedsgACC,butbluntedstriatalresponseinMDDacross differentreward,affectiveandsocialprocessingparadigms,evenin remission.However,besttoourknowledgethereisnostudywhich hasinvestigatedbrainimagingcorrelatesofsocialrewardprocessing impairmentsinremittedorcurrentMDD.Basedontheevidencere- viewedabove,wesuggestthatdecisionstomakecharitabledonations maybeanexperimentalprobeforunderstandingfunctionalimpair- mentsrelatedtosocialdecision-making,associatedwithabnormality offronto-meso-limbicnetworks.

Here,weusedfunctionalmagneticresonanceimaging(fMRI)with an experimentalcharitabledonationsparadigmto investigate the neuralbasesofaltruisticdecisions inMDD. Traitabnormalitiesin donationbehaviourhavebeenpreviouslysuggestedbyanepidemio- logicalstudy(Fujiwara,2009).Inordertoinvestigatetheneuralbasis ofdonationbehaviourassociatedwithdepressionvulnerability,we recruitedunmedicatedpatientswithMDDfullyremittedfromsymp- toms(rMDD)andagroupofmatchedcontrolswithnopersonalor familyhistoryofMDD.Agrowingnumberofstudiessuggestthat usingfunctionalneuroimaginginrMDDisavalidapproachtoinves- tigatingbiologicaltraitmarkersforfuturemajordepressiveepisodes (BhagwagarandCowen,2008;Dichteretal.,2012;Elliottetal.,2012; Nixonetal.,2014;Schilleretal.,2013;Pulcuetal.,2014).Studying remittedMDDhasadditionaladvantagessuchasmitigatingtheef- fectsofcurrentmoodstateandantidepressantmedications(Dichter etal.,2012;Schilleretal.,2013).Here,weinvestigatedthefollowing hypotheses,basedonpreviousliteraturereviewedabove:compared

withcontrols,peoplewithrMDDwouldexhibit1)enhancedsgACC responsetodonationdecisionsrelativetosimplemonetaryrewards and2)reducedresponsestorewardsinstriatalregions(e.g.septal, nucleusaccumbens,caudate,globuspallidus).

2. Materialandmethods 2.1. Participants

WeobtainedethicalapprovalfromtheNorthWest

/

ManchesterSouthNHSResearchEthicsCommittee.Participantswererecruited usingonlineandprintadvertisements.Initialsuitabilitywasassessed withaphonepre-screeninginterviewandanonlinesurvey.Written informedconsentwasobtainedfromallparticipants.

2.1.1. Inclusion

/

exclusionofparticipantsPatientswithrMDDfulfilledthecriteriaforapastmajordepressive episodeinfullremissionaccordingtoDSM-IV-TR(AmericanPsychi- atricAssociation,2000).Theclinicalinterviewswereconductedby trainedresearchers(seebelow).Weexcludedpeoplewithcurrent MDD,currentorhistoryofsubstanceusedisorders,psychoticdisor- ders,bipolardepression,anyAxis-Ianxietydisordersdiagnosedprior totheinitialmajordepressiveepisodeoranyhistoryofneurological disorders.Wealsoexcludedpatientsusingpsychotropicmedication.

ThehealthycontrolgroupadditionallyhadnocurrentorpastAxis-I disordersandhadnofirst-degreerelativeswithahistoryofAxis-I disorders.Allparticipantshadnormalorcorrected-to-normalvision.

Intotal,15healthycontrolparticipantsand14individualswith rMDD(seeSupplementarymaterialsTable1forfurtherclinicalinfor- mation)wereincludedinthefinalanalysis.OnepatientwithrMDD andone healthysubjectwereexcludedbecauseofan insufficient numberofacceptancesinthesimplefinancialrewardcondition(see belowforthedetailsofthefMRIparadigm).

2.2. Clinicalinterviewprocedure

Participantswereinvitedforaclinicalinterviewinwhichtrained researchers(EJTorPDT)conductedtheMoodDisordersModuleAand thepsychoticscreeningoftheStructuredClinicalInterviewforDSM- IV-TR(SCID)(Firstetal.,2002).TheMINIscreening(MiniInternational NeuropsychiatricInterview;Sheehanetal.,1998)wasconductedwith allparticipantsandrelevantStructuredClinicalInterviewforDSM-IV- TR(SCID)moduleswereusedinordertomakeafullassessment.The MontgomeryAsbergDepressionRatingScale(MADRS)(Montgomery andAsberg,1979)andtheGlobalAssessmentofFunctioning(GAF) scale(AxisV,DSM-IV)wereusedtoassesscurrentsymptomsand socialfunctioning.

2.3. fMRIparadigm

ThecharitabledonationstaskwasadaptedfromMolletal.(2006) andthechoiceofcharitieswasbasedonthefindingsofaprevious pilotstudy,whichinvestigatedpeople’sperceptionsandpreferences aboutcharitableorganisationsinEnglandandWales.Missionstate- mentsof95charitieswereobtainedfromTheCharityCommissionfor EnglandandWales(http:

//

www.charity-commission.gov.uk/

)forthepilotstudy.The36charitableorganisationswiththemostpositive missionstatementratingsinthepilotwereselectedforthefunc- tionalneuroimagingtask. UnliketheMolletal.(2006) study,our imagingparadigmdidnotcontainanycharitiesprobingcostly

/

non-costlyoppositionbehaviour.Thisdecisionwasbasedonthefindings ofthepilotstudyinwhichweonlyidentified11charities(predomi- nantlyfocusingoncontroversialreligiousthemes)withmildlynega- tivemissionstatementratings(adetailedanalysisofthepilotstudy isavailablefromtheauthorsuponrequest).Ourpilotfindingsmay reflectasignificantculturaldifferenceincharitiesbetweentheUS

andtheUK.UScharitiesincludepoliticalorganisationsandlobby- inggroups,forexamplecharitiespromotingguncontrolorabortion, which elicitstrongoppositioninsomepeople andstrongsupport inothers(Wright,2002).RegisteredUKcharitiesaregenerallyless politicisedand,whilepeoplearemoreorlesslikelytosupportthese charities,thereareveryfeworganisationswhichpeoplewouldac- tivelyoppose(andstillfewerwhichpeoplewouldpaytooppose).

BeforethefMRIexperiment,participantsweregivenadocument containingthefullnameandthemissionstatementof36charities andthepayoffconditionswereexplainedtothem(seeTable1for payoffsandtheircomparisonwithMolletal.(2006)).

ThecharitabledonationstaskperformedduringfMRIlastedfor 144rounds(3runs;48roundsineachrun)withthefollowingcondi- tionspresentedinpseudorandomorder:

Costlydonation:Charitygains,participantloses

Non-costlydonation:Charitygains,participantneithergainsnor loses

Reinforcingdonation:Charitygains,participantgains

Simplefinancialreward:Participantgains,charityneithergains norloses

Neutral:Nogainorlossforeithercharityorparticipant.

SeeTable1forcost, donationandrewardmagnitudesineach condition.Intotal,therewerethreedonationconditionswherethe charitygains:reinforcingdonation(participantalsogains),non-costly donation(nochangeforparticipant)andcostlydonation(cost

/

lossforparticipant).Thecostlyconditionbestmodelsreal-lifecharitable giving.Donationsinthecostlyproposalsreducedparticipants’en- dowmentby30p(p=pence,1

/

100thof£1,1UKpound),whichisthenescalatedintheexperimentaldesignofthestudy(asinMollet al.2006)andcorrespondedto£1ofdonationtothecharity.

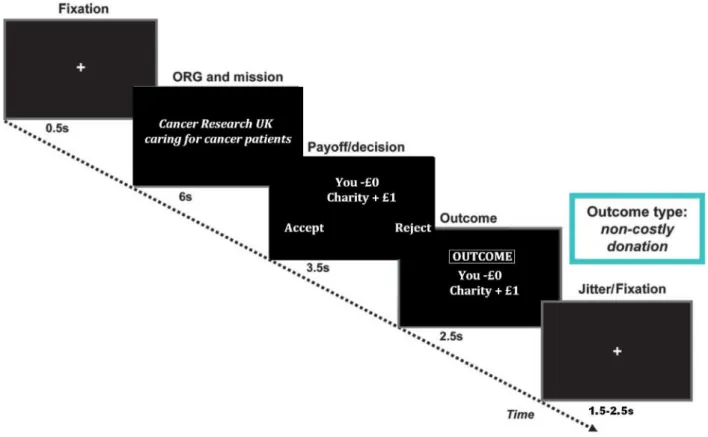

Duringtheexperiment,participantsstartedwith£20offundscor- respondingtorealcurrency.Ineachround,charityinformationwas presented totheparticipants,comprisingthenameofthecharity andashortenedversionofits missionstatement(for6s).Onthe nextscreen,theparticipantssawthepayoffconditions(for3.5s).

Participantsrespondedby usingthedesignated“Accept” and“Re- ject” buttonstoindicatetheirdecisions;thedesignationofthesetwo buttonswascounterbalancedacrossparticipants.A20ppenaltywas imposedwhenparticipantsfailedtorespondwithin3.5s.Thepay- offscreenremainedvisibleuntil3.5sexpired,irrespectiveofhow quicklyparticipantsrespondedtotheproposal.Onthefinalscreen, participantswerepresentedwiththeoutcomeoftheirdecisionsand theamountofremainingfunds(for2.5s;seeFig.1forthesequenceof screensonexperimenttimeline).Attheendofthegame,theamount ofremainingfundswasroundedtothenearestlbtobereceivedas reimbursementforparticipation.Theparticipantsweretoldthatall ofthedonatedmoneywouldbedistributedevenlytothefivemost frequentlyselectedcharitiesoncethestudywascompleted,andin adebriefingsession,noparticipantquestionedwhetherthesedona- tionswouldbemade.

2.4. Imageacquisition

Echo-planarT2*-weightedimages(351volumesineachofthe3 runswith5dummyscansforeach runof11min42s)wereac- quired onaPhilips 3TeslaAchieva MRIscanner withan 8chan- nelcoil,3mmslicethicknessandascendingcontinuousacquisition parallel totheanterior toposteriorcommissuralline(between35 and40slicesdependingonsizeofthe participant’shead,Repeti- tionTime(TR)=2000ms,EchoTime(TE)=20.5ms,FieldofView (FOV)=220 × 220 × 120mm,acquisitionmatrix=80× 80,re- constructedvoxelsize=2.29 × 2.29 × 3mm,SENSEfactor=2) optimised for signal detection in ventral frontal areas (Green et

al.,2012b).Inaddition3-dimensionalT1-weightedMagnetisation- PreparedRapidAcquisitionGradientEchostructuralimageswereob- tained(reconstructedvoxelsize=1mm3,128slices,TE=3.9ms, FOV= 256 × 256 × 128,acquisitionmatrix=256 × 164,slice thickness=1mm,TR=9.4ms).AxialT2-weightedstructuralimages wereacquiredforeachparticipanttoruleoutvascularandinflam- matoryabnormalities.

2.5. fMRImodelling

Wemodelledthehaemodynamicresponsefunctionwithtimeand dispersionderivatives.Thefiveconditionspecificregressorsinthe generallinearmodelwere:neutral(neithertheparticipantnorthe charitygainsorlosesmoney),costly(charitygains,participantloses), non-costly(charitygains,nochangeforparticipant)andreinforcing (charityandparticipantbothgain)donationconditionsandsimple financialreward(participantgains).Thebaselinefixationcondition wasmodelledexplicitlyasthesixthregressor,inordertoreplicate theanalysisapproachusedbyMolletal.(2006).Theregressorsin themodelreferredtoonsettimevectorsforallproposalsthatwere accepted(andfixationonsetforthebaseline).Ourevent-relatedfMRI paradigmismodelledinthesamewayasMolletal.(2006).Insum- mary,wemodelledthe3.5scorrespondingtothepresentationofthe proposal(payoff

/

decisionscreeninFig.1),duringwhichparticipants madetheirdecisions.Thisisthe“decisionphase” analysis.Wealso modelledthe6swindowcontainingboththepayoff/

decisionandoutcomescreens(seeFig.1)todetectoutcomerelatedactivations.

Thisisthe“outcomephase” analysis.Sincetheoutcomeisfullypre- dictableifthepayoffisaccepted,theoutcomeisknownfromthe pointatwhichtheproposalispresentedandacceptedandtherefore itmakessensetomodelthisphaseincludingthedecisionscreen, followingtheapproachofMolletal.(2006).

2.6. Analysis

Behaviouralandsupporting dataanalyseswereperformed us- ingasignificancethresholdofp=0.05,2-sided;usingchi-square, independentsamplet-tests andgeneral linearmodels(SPSS 20.0, http:

//

www.spss.com).Functionalimageswererealigned,unwarped andcoregisteredtothesubject’sT1images.Theseimageswerenor- malisedbyfirstnormalisingtheparticipant’sT1imagetothestan- dardT1-templateinSPM8(http://

www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/

spm/

)andapplyingthesametransformationstothefunctionalimages.AGaus- siankernelof5mmatfullwidthathalfmaximum(FWHM)was usedforsmoothingtobesensitivetosmallsubcorticalareasofacti- vation(SacchetandKnutson,2012).Atthefirst(individual)levelwe contrasteddonation(containingallacceptedcostly,non-costlyand reinforcingdonationproposals)vs.reward(simplefinancialreward) inabalancedcontrast.Subsequently,wecontrastedtheseproposal optionsinpairwisecomparisons(e.g.costlyvs.non-costly,costlyvs.

reward,non-costlyvs.reward)andcontrasted eachproposalcon- dition againstthe baseline conditions of neutral andfixation. At thesecondlevel,weusedthecontrastimagesfrompairwisecom- parisonsintwodifferentrandomeffectsmodels.Usingone-sample t-testsinourfirstmodel,weassessedneuraldifferencesbetween conditionsseparatelyinhealthysubjects(n=15)andinremitted patients(n=14).Usinga two-samplet-testinoursecondmodel wecomparedthegroups.Insecondarydataanalysesbasedonthe peak-voxels ofthe wholebrain between-group comparisonmod- els(usinga1.5mmradiusaround thepeakvoxelinMarsBarver- sion0.43,http:

//

marsbar.sourceforge.net/

(Brettetal.,2002)),weaimedtoconfirmthatthedetectedregionssurvivedwhencompar- ingdonation

/

rewardproposalsvs.thelow-levelfixationcondition,allowingustoinfereitherincreasedactivationfortheacceptanceof theproposalordeactivationinthesubtractedcontrolcondition.

Table 1

The payoffs for the participant and the charity across different conditions and comparisons between Moll et al. (2006) .

Participant Charity

Total number of conditions (out of

144) Participant a Charity a

Total number of conditions a

Funds £20 N /A N /A $128 N /A N /A

Costly −30p + £1 36 −$2 + $5 32

Non-costly −0p + £1 36 −$0 + $5 32

Reinforcing + 10p + £1 24 N /A N /A N /A

Reward + 10p + £0 24 + $2 + $0 32

Neutral −0p + £0 24 N /A N /A N /A

Null-fixation + + 144 + + 48

Penalty −20p N /A N /A −$1 N /A N /A

The financial magnitude of proposals in the current study is written in bold (i.e. left side of the table). aDetails and the frequency of the conditions in the Moll et al. (2006) study is presented on the right side of the table. Moll et al. (2006) also contained costly and non-costly opposition proposals which were not included in the present study due to differences in charitable giving between the US and the UK. At the time of writing this manuscript, $2 converted to £1.20. The main difference between the studies is the relative magnitudes of financial components of the conditions; for Moll et al. (2006) : penalty <reward = costly donation <charity amount; whereas in the present study: reward <penalty <costly donation <charity amount. Greater financial magnitude for penalty over reward is preferred in the present design in order to reduce the number of trials with no responses. The ( + ) denotes the pattern of fixation. N /A: not applicable information.

Fig. 1. Diagram showing the experimental timeline of the charitable donations paradigm.

Adapted from Moll et al. (2006) .

Wholebrainresultswerefirstexploredatavoxel-levelthreshold ofp=0.005uncorrected, clusterthreshold4voxels.However,ar- easareonlyreportedthatsurvivedadditionalvoxel-orcluster-level Family-Wise-Error(FWE)-correctedthresholdsofp=0.05acrossa prioriROIs(asdetailedbelow,smallvolumecorrection)orthewhole brain.

2.7. Regionofinterest(ROI)definition

Wedefinedindependentstructuralregionsofinterestwhichwere previouslyshowntobeinvolvedindecisionstomakecharitabledo- nationsandarealsocriticallyassociated withdepression(septal

/

subgenualcingulateregionandbilateralstriatum).Inanexploratory fashion,wealsoinvestigatedtheactivationsintwoadditionalregions whichareassociatedwithsocialeconomicaldecisionmaking;dorsal

anteriorcingulateandventromedialprefrontalcortex(Pulcuetal., 2013).TheROIsweredefinedbyusingtheWakeForestUniversity (WFU)PickAtlastool(Maldjianetal.,2003)forSPM8;usingacombi- nationofanatomicalandBrodmannAreamasksfromtheautomated anatomicallabels(seeSupplementarymethodsforthedetails).

3. Results 3.1. Participants

Thegroupsdidnotdiffersignificantlyforage,yearsofeducation, distributionofgender,annualincomeorMADRSscores(seeTable2).

Table 2

Group comparison of demographic and basic clinical variables (mean ±SD).

Control Remitted MDD Test statistic p -Value

Age 38.9 ±5.9 38.1 ±6.3 0.346 T 0.732

Education (years) 17.5 ±4.1 16.8 ±3.5 0.548 T 0.588

Gender 9 females 12 females 0.895 a 0.344

Income (GBP) 23,835 ±8752 22,173 ±9521 0.488 T 0.629

MADRS 2.35 ±2.17 2.6 ±2.9 −0.254 T 0.801

GAF 91 ±4.1 87.6 ±5.9 1.968 T 0.059

T Denotes t-test.

aPearson’s chi-square (df = 1). T = t-test. Control: N = 15, remitted MDD: N = 14. Patients with remitted major depression had a trend towards lower GAF scores compared with healthy subjects.

3.2. Behaviouralresults

Therewerenodifferencesbetweengroupsinthenumberofac- ceptanceresponsestoanyofthedonationortherewardconditions orresponsetimesforacceptanceorrejectioninanyoftheconditions (see Table3).Furthermore,thegroupsdidnotdifferonhowthey ratedthemissionstatementsofthecharitableorganisationsandhow muchtheywerefamiliarwiththecharitableorganisationspriorto theirparticipation.

3.3. fMRIresults

SummaryofallfMRIactivationsisreportedinTable4.

3.3.1. Healthysubjects

3.3.1.1.Decisionphase.Againstbaselinefixation,decisionstodo- natewereassociatedwithincreasedBOLDresponseinthefrontopolar andlateralorbitofrontalcorticesandtheseptalregion.Whencompar- ingdecisionstoacceptsimplerewardsvs.makingcostlydonations, healthysubjectsshowedanenhancedresponseinthedorsalante- riorcingulatecortex(seeTable4).Thecomparisonsbetweenother mainconditionsinpairwise contrasts(i.e.alldonation vs.reward, non-costlyvs.reward,costlyvs.non-costly)showednosignificantly differentresponses.

3.3.1.2.Outcomephase.Outcomesinalldonationandrewardcon- ditionsagainstthelow-levelfixationbaseline(i.e.allthreedonation conditions + reward

>

fixation)inhealthysubjectswereassoci-atedwithincreasedresponsesinthesgACC,septalregionandven- tromedialprefrontalcortex,whereasoutcomesforacceptingsimple rewardswereassociatedwiththemedialtemporalgyribilaterally,in- feriorfrontalgyrus,ventromedialPFCandseptal

/

nucleusaccumbensregionandsubgenualcingulatecortex.

3.3.2. PatientswithremittedMDD(rMDD)

3.3.2.1.Decisionphase.IncreasedBOLDresponserelatedtodeci- sionstomakecharitabledecisions(irrespectiveofpersonalcosts)to acceptingsimplemonetaryrewards(i.e.alldonation

>

rewardcon-trast);aswellasdirectcomparisonofcostlydonationstoaccepting simplemonetaryrewardsdidnotreachFWE-correctedsignificance level.

3.3.2.2.Outcomephase.SignificantlyincreasedBOLDresponsere- latedtooutcomesincreasingthecharity’sandone’sownfinancial resourcesagainstthebaselinecondition(i.e.allthreedonationcon- ditions +reward

>

fixation,seeTable4)wasdetectedinthesgACC.Theinferioraspectoftheglobuspalliduswithintherightstriatum, aswellastheseptalregion,alsoshowedincreasedresponse.Out- comesrelatedtomakingdonationsrelativetothebaselinefixation crosswereassociatedwithBOLDresponseinthesgACC,striatum, headofcaudateandseptal

/

nucleusaccumbensregions.Outcomesrelatedtoacceptingsimplefinancialrewardsrelativetothebaseline fixationdidnotproduceanysignificantchangeinBOLDresponseat FWE-correctedthreshold.

3.3.3. Betweengroupcomparisons

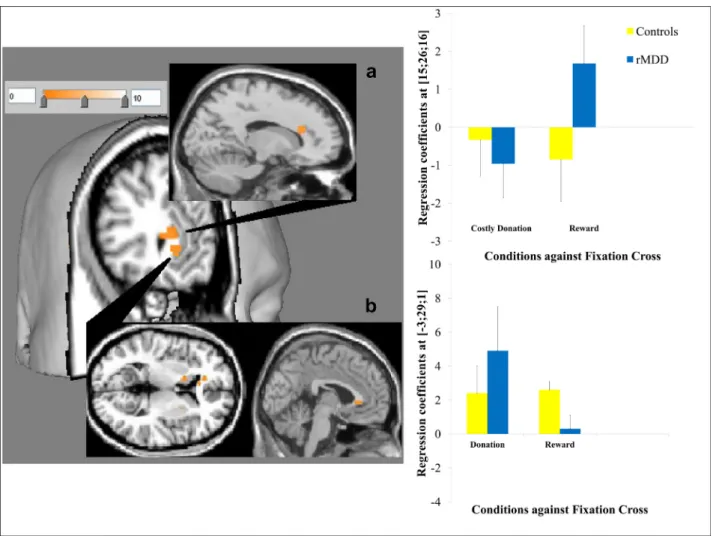

3.3.3.1.Decisionphase.Whencomparingallthreedonationdeci- sionstosimplerewards,therewasincreasedsgACCresponseinthe rMDDgrouprelativetocontrolsubjects(BA24;MNI:−3,29,1;t=4.1, FWEcorrectedoverROI:p=0.04;seeFig.2).Whencomparingdeci- sionstomakecostlydonationvs.reward,therewasincreaseddorsal anteriorcingulatecortexresponseincontrolsubjectsrelativetothe rMDDgroup(BA31;MNI:15,26,16;t=4.4,FWEcorrectedoverROI:

p=0.05;seeFig.2).

3.3.3.2.Outcomephase.Finally,therewasincreasedstriatumre- sponseintherMDDgrouprelativetocontrolsubjectswhencompar- ingallreward-relatedoutcomestofixation(i.e.alldonation + re- ward

>

fixation;MNI:18,20,1;t=3.94,FWEcorrectedoverROI:p=0.05;seeFig.3).Enhanceddonationspecificresponse(i.e.alldona- tionconditions

>

fixation)intheremittedgroup,relativetohealthysubjects,wasfurtherconfirmedbypost-hocSPManalysisshowinga significantactivationinthenucleusaccumbensextendingmedially totheseptalregionadjacenttothesgACC(MNI:21,14,−14,t=4.73, p=0.04).

Betweengroupcomparisonsforothermaincontrasts(i.e.non- costlyvs.reward;costlyvs.non-costly)didnotrevealanysignificant responsedifferencesinourROIsineitherthedecisionoroutcome phases.

3.3.4. Supportinggenerallinearmodels

The between group differences that we present above reflect groupbyconditioninteractions.Inordertoconfirmgroupbycon- ditioninteractionsweusedextracted regressioncoefficientsfrom thepeakvoxelsfortheconditionsofinterestcomparedtobaselinein 2×2GLMsinSPSS(twotypesofdecisions(e.g.todonateortoaccept simplerewards)bytwolevelsofclinicalgrouping).Thissubsequent analysisprovidesausefulcheckfortherobustnessofbetweengroup differencesasSPMminimisestheresidualerroroverthewholebrain (i.e.least-squaresfitting)inGLMs,whereasusingregressioncoeffi- cientsextractedbyMarsBarinSPSSallowsustotestthesuitabilityof thesewholebrainmodelstospecificregions.Inordertounderstand thesimpleeffectsdrivingbetweengroupinteractions,wedidpair- wisecomparisonsusingextractedregressioncoefficientsfromthe peakvoxelsfortheconditionsofinterestcomparedtobaseline(see betweengroupdifferencespresentedinFigs.2and3).

ForthesgACCresponseinthedecisionphase(alldonation

>

re-ward),therewasasignificantdecisiontypebygroupinteraction(F(1, 24)=9.694,p=0.005)withmaineffectofdecisions(F(1,24)=4.944, p=0.036),butnomaineffectofclinicalgroup(p=0.408).Pairwise comparisonswereusedtoexploretheinteraction.Relativetohealthy subjects,therewasasignificantlyreducedresponseforreceivingsim- plerewards(t=2.295,p=0.05),andmarginallyelevatedresponse tomakingdonations(t=−1.796,p=0.09)inremittedpatients.The magnitudeofdonationrelatedactivationrelativetosimplerewards wassignificantlyhigherinremittedpatients(t=3.887p=0.001), whereasitwascomparableinhealthysubjects(t=−0.123,p=0.903;

seeFig.2b).

Table 3

Behavioural measures and response time (RT) comparisons (ms).

Control (mean ±SD) Remitted MDD (mean ±SD) T a p -Values

Donation count

Costly 18.9 ±9.4 22.5 ±10.7 −0.943 0.354

Non-costly 30.9 ±6.7 33.6 ±4.5 −1.270 0.215

Rewarding 22.3 ±3.1 23.3 ±1.8 −1.104 0.28

Simple financial reward 21.1 ±3.6 22 ±2.1 −0.794 0.434

Neutral 13.6 ±9.5 16.3 ±9.4 −0.769 0.449

Total funds ( £) 18 ±2.4 17.6 ±3.1 0.351 0.729

Charity ratings

Familiarity 3.05 ±0.9 2.8 ±0.6 0.741 0.465

Mission statement 5.3 ±0.7 5.2 ±0.5 0.401 0.692

Costly donation

Acceptance RT 1604 ±311 1562 ±420 0.307 0.761

Rejection RT 1567 ±396 1608 ±418 −0.269 0.79

Non-costly donation

Acceptance RT 1338 ±329 1454 ±557 −0.677 0.504

Rejection RT 1406 ±523 1639 ±579 −1.129 0.269

Rewarding donation

Acceptance RT 1394 ±522 1318 ±392 0.445 0.66

Rejection RT 1710 ±708 1475 ±446 1.074 0.292

Simple financial reward

Acceptance RT 1366 ±530 1608 ±545 −1.209 0.237

Rejection RT 1452 ±584 1476 ±406 −0.128 0.899

The groups do not differ on acceptance of donation proposals or any of the response times (control group: N = 15, rMDD group: N = 14).

aIndependent sample t -test (df = 27).

Table 4

Summary of BOLD fMRI results.

Comparison Hemisphere Region MNI t -Value FWE-corr. p -value

X Y Z

Controls Donation + re-

ward >fix L Ventromedial

PFC

−9 47 −14 6.74 .01 c,ROI

L Septal −3 23 −2 4.08 .02 c,ROI

L Subgenual

cingulate

−12 29 −8 5.36 .02 c,ROI

Donation >fix R Frontopolar

cortex

6 65 −5 5.97 <.001 c,ROI

R Lateral OFC 21 35 4 4.99 .02 c,ROI

L Septal −3 23 −2 3.90 .04 c,ROI

Reward >fix L Ventromedial

PFC

−9 47 −14 8.04 <.001 wb

L Temporal gyrus −63 −7 −14 8.07 .001 wb

R temporal gyrus 63 −4 7 5.78 <.001 wb

R Inferior frontal

gyrus 42 29 −14 4.73 .04 wb

R Subgenual

cingulate

15 29 −8 4.49 .05 wb

R Septal /nucleus

accumbens

3 20 4 4.74 .02 c,ROI

Reward >costly L Dorsal ACC −6 32 7 5.6 .03 c,ROI

Remitted MDD Donation + re- ward >fix

R Subgenual

cingulate

12 35 −14 6.82 .001 c,ROI

L Septal −3 17 −5 4.41 .02 c,ROI

R Striatum 30 −4 −11 5.54 .03 c,ROI

Donation >fix R Subgenual

cingulate

12 35 −14 8.29 .005 wb

R Striatum 30 −4 −11 5.57 .04 c,ROI

R Head of caudate 15 23 13 5.56 .05 c,ROI

L Septal /nucleus

accumbens

−6 17 −8 5.58 .01 c,ROI

Control vs. rMDD

Costly >reward R Dorsal ACC 15 26 16 4.4 .05 v,ROI

rMDD vs. control Donation + re- ward >fix

R Striatum 18 20 1 3.94 .05 v,ROI

Donation >fix R Nucleus

accumbens

21 14 −14 4.73 .04 v,ROI

Donation >re- ward

L Subgenual

cingulate

−3 29 1 4.1 .04 v,ROI

Only regions that survived voxel- or cluster-based FWE-corrected p = .05 over the whole brain or our a priori ROIs are reported. wb = whole brain, c = cluster-based, v = voxel-based FWE-correction. Control group: N = 15, remitted MDD group: N = 14. fix: Fixation cross.

Fig. 2. 3D rendering and overlays constructed by Mango brain imaging software. T-maps displayed at p <0.005 uncorrected showing activation in (a) the dorsal anterior cingulate in healthy subjects relative to MDD for costly donation >reward with regression coefficients from the peak voxel for the contrast elements against the fixation shown in bar charts (as with for other activations in the figures; error bars show ±1 standard error) and (b) the subgenual cingulate in MDD relative to healthy subjects for all donation >reward.

Fig. 3. Activation in the right striatum in MDD relative to healthy subjects for all donation + reward >fixation.

ForthedACCresponseinthedecisionphase(costlydonation

>

re-ward),therewasasignificantdecisiontypebyclinicalgroupinterac- tion(F(1,24)=10.336,p=0.004)withmaineffectofdecisiontype (F(1,24)=5.686, p=0.025),butnomaineffectofclinicalgroup (p=0.390).Betweengrouppairwisecomparisonsforsimplemainef- fectssuggestedthatthegroupsweremarginallydifferentforreward relatedresponses(t=−1.757,p=0.09).Relativetothemagnitude ofresponsesforsimplerewards,remittedpatientshadsignificantly lowerresponseforcostlydonations(t=−2.182,p=0.04),whereas inhealthysubjectsthemagnitudeofthedeactivationsforbothcon- ditionswascomparable(t=0.372,p=0.713;seeFig.2a).

Fortherightstriatalresponseintheoutcomephase(alldona- tion + reward

>

fixation),therewasasignificanttypeofoutcomebyclinicalgroupinteraction(F(1,24)=13.159,p=0.002)withmain effectofoutcometype(F(1,24)=6.410,p=0.02)andmaineffectof clinicalgroup(F(1,24)=16.763,p=0.0006).Betweengrouppairwise comparisonssuggestedthattheinteractionisdrivenbysignificantly elevatedresponsesfordonationconditions(t=−4.161,p=0.001), butbetweengroupdifferenceswerenon-significantforsimplere- wards(t=−1.875,p=0.08).Therightstriatalactivationsforboth conditionsrelativetothebaselinewerecomparableinremittedpa- tients(t=1.029,p=0.315),butinhealthysubjectsthedeactiva- tionsweresignificantlygreaterfordonationconditions(t=−3.476, p=0.002;seeFig.3).

3.3.5. Exploratorycorrelationanalysis

InordertoexplorefurtherthedACCresponseduringthedecision phase,weinvestigatedthecorrelationsbetweentheregressioncoef- ficientsandbehaviouralmeasuresrelatedtothedecisions:response timesand frequencyfor acceptingdonation or rewardproposals.

TherewasapositivecorrelationbetweendACCregressioncoefficients forreward

>

fixationandresponsetimesfordecisionstoacceptsim-plefinancialrewardsintherMDDgroup(df=13,r=0.573,p=0.041);

whereasaninversecorrelationemergedbetweenthismeasureand thenumberofsimplefinancialrewardsacceptedinhealthysubjects (df=14,r=−0.634,p=0.011;p-valuesuncorrected;seeFig.2a).

4. Discussion

Here,weconductedafunctionalneuroimagingstudyusinganex- perimentalcharitabledonationsparadigminordertoinvestigatethe neuralbasisofaltruisticdecisionsinpatientswithremittedMDD.

Ourbehaviouralresultsforcostlydonationandacceptingsimplefi- nancialrewards(seeTable3)suggestedthattheexperimentaltask effectivelyprobeddonationrelatedfinancialdecision-making;with allparticipantspreparedtomakecostlydonationseventhoughthese decisionsreducedtheiroverallgainsfromthetask.Weshowedthat duringperiodsofremission,patientswithMDDdidnotengageinal- truisticdecisionssignificantlymorefrequentlythanhealthysubjects.

However,ourimagingresultsindicatethataltruisticdecisionsare associatedwithenhancedseptal

/

sgACCresponseinremittedMDDcomparedtocontrols.Wealsoshowedthatoutcomerelatedstriatal responsesarerelativelyenhancedinrMDDcomparedtocontrolsfor bothcharitableandself-servingdecisions.Finally,weshowedthat inremitted patientsthereisenhancedresponse indACC fordeci- sionstoacceptsimplefinancialrewards,andadecreasedresponse (i.e.negativeBOLDeffect)inthisregionfordecisionstomakecostly donations.

Wewereonlypartiallyabletoreproducethefindingsofaprevious donationstudyinhealthyvolunteers(Molletal.,2006).Weshowed thatinhealthysubjectscharitabledecisions,aswellasacceptingsim- plefinancialrewards,activatedoverlappingneuralcircuitrywiththe Molletal.(2006)study,butconditionspecificactivationswereonly detectedagainstthebaseline condition. Thesedifferencesmaybe duetothedifferencesincharitableorganisationsusedacrossthetwo experimentalparadigms,andinparticulartothedifferencesinthe natureofcharitablegivingbetweentheUnitedStatesandtheUnited Kingdom(Wright,2002).Onekeydifferenceinthenatureofcharita- blegivingbetweenthesetwocountriesisthatintheUS,donations contributetotaxrelief(Harbaughetal.,2007)andthereforethere maybenon-altruistic incentivestodonate.IntheUK,onlyhigher earners,whopayincometaxatahigherrate,receivetaxreliefon donationsandnoneofourparticipantsreportedannualincomesthat wouldincludetheminthistaxbracket.Also,Wright(2002)argued thatcharitablegivingisoftenaformofpoliticalexpressionintheUS, wherecontroversialmissionobjectivesofmanycharitableorganisa- tionsarelikelytodividepublicopinion(asreflectedinthesubsetof charitieswhichprobedoppositionbehaviourinMolletal.(2006)).

TherearefarfewercontroversialcharitableorganisationsintheUK andwewerethereforeunabletoexamineopposition.Thisdifference inthenatureofthecharitiesmayalsoexplainwhywedidnotrepli- cateallofthepreviouslyreportedresults.

Ourcorehypothesesconcerneddifferentialresponsesbetweenin- dividualswithrMDDandhealthycontrols.Aspredicted,weshowed increasedresponseinthesgACCregionfordecisionstodonaterela- tivetosimplemonetaryrewardswhichdistinguishedtherMDDfrom thecontrolgroup.AbnormalfunctioningofthesgACCinMDDiswell establishedinclinicalresearch.Followingvolumetriccorrectionfor thereductioningreymatter,anabnormalhypermetabolisminthe sgACChasbeenshownincurrentdepression(DrevetsandSavitz, 2008),whichnormalisesuponremissionfromsymptoms(Mayberg etal., 2000).Here weobserved enhanced sgACCresponse during remission,inresponsetoaspecificcognitivechallenge,suggesting someresidualhypersensitivitywhichcanbeelicitedwithasuitable taskprobe.Itisimportanttopointoutthatthepeakactivationin thesgACCthatwereportinourbetweengroupscomparisonisal- mostpreciselyoverlappingwiththepeakoffunctionalabnormality reportedbyDrevetsetal.(1997).

Previousimaging studieshave implicatedthe sgACCin proso- cialdecision-making,affiliativefeelingsandmoralemotions,such asinterpersonal(Zahn etal.,2009b) andaltruistic guilt(Basileet al., 2011b), empathic concernfor others(Zahn etal., 2009a) and compassionforother’spsychologicalpain(Immordino-Yangetal.,

2009).Lesionstoventromedialpartsoftheprefrontalcortex(Koenigs andTranel,2007)haveshowntoinfluenceprosocialdecisionsneg- ativelyininterpersonalfinancialexchange.Morespecifically,septal neurodegenerationhasbeenassociatedwithalackofaffiliativefeel- ingssuchasguiltandpity(Molletal.,2011),suggestingthatthese prosocialemotionsareimportantforbalancingselfishmotivesinso- cialeconomicaldecisionmakingsituations.Ourcharitabledonations paradigmelicitedenhancedsgACCresponseinremittedMDD,sug- gestingthatdonationmaybeamoresensitiveprobeofsgACCfunction inthisgroupthanparadigmsexploringinterpersonalguilt(Greenet al.,2012b),whichdidnotleadtobetweengroupBOLDsignaldiffer- encesinthesgACC.GiventheliteraturerelatingsgACCtoprosocial, affiliativeandmoralemotions,itisreasonabletosuggestthatsuch feelingsaremorestronglyelicitedinpeoplewithremittedMDDthan controlsduringcharitabledonations.Morespecificallyithasbeenar- guedthatformsofguilt,particularlysurvivorguilt,maybeimportant motivationsformakingcharitabledonations.Itisthereforepossible that theenhancedseptal

/

sgACCresponseduringdonationsinpa-tientswithrMDDreflectsthehigherlevelsofsurvivorguiltthathave beensuggestedtounderpinhyper-altruisminthisgroup(O’Connor, 2012).Howeverwhilethisisareasonablehypothesisarisingfromour presentfindings,itrequiresdirecttestinginfuturestudies,asguilt isonlyonecomponentofsocialdecision-makingwhichadonations taskpotentiallyprobes.

Countertoourhypothesis,weobservedenhancedsignalinthe striatuminremittedMDD,particularlyfordonationoutcomes.Meta- analyticalreviewsshowthatthestriatumrespondsduringthepre- diction andconsumptionofsalientrewards(Diekhofetal.,2012), whetherprimaryorsecondary(Sescousseetal.,2013).Thestriatal responsesobservedinthestriatuminhealthycontrolswerelower thanweexpected.Thismayreflecttherelativelypassivenatureof thetask,aspreviousstudiesindicatedthatcompetingfor,orwin- ning,financialrewardsunderconditionsofuncertaintyisassociated withgreaterstriatalresponsesrelativetopassivereceiptofsimplere- wards(Elliottetal.,2000).Anotherexplanationfortherelativelysmall magnitudeofstriatalactivationsinourcontrolgroupmaybethatthe magnitudeofoursimplerewardswasmuchsmallerthanthatused byMolletal.(2006)(seeTable1andlegendsfordetailedcompari- son).Culturalandtaskspecificdifferencesbetweenthepresentstudy andMolletal.(2006)mayalsobeimportantfactors.However,these argumentsdonotexplaintherelativelyincreasedstriatalresponses observedintheremittedgroup.Previousstudieshavesuggestedre- ducedstriatalresponsestofinancialrewardsinpeople withMDD, whichmaypersistintoremission(Tremblayetal.,2005;Schlaepfer etal.,2008;Knutsonetal.,2008;EshelandRoiser,2010).Ourfindings suggestthatdecisionstomakecharitabledonationsenhancestriatal responsesinrMDD,perhapsreflecting enhancedsensitivitytoso- cialrewards.However,onceagain,thisisahypothesisthatrequires testinginfuturestudies.

Despiterelativepaucityofdirectlycomparableevidenceinthelit- erature,herewepresentnovelfindingsofenhancedresponsetochar- itabledecisionsinouraprioriROIs(sgACCandstriatum)detectedin theabsenceofbehaviouraldifferences.Thesepresentfindingsaddto agrowingnumberofstudiesshowingevidenceforabnormalsocial perceptionandsocialemotionprocessingeveninperiodsofstable remission.Forexample,previousstudiesfromourresearchgroup showedthatpatientswithremitteddepressionhavedisruptedfunc- tionalconnectivitybetweenthesgACCandtherightanteriortemporal lobeforguilt(Greenetal.,2012b)andenhancedBOLDresponseinthe rightamygdalaforshamewhileratingunpleasantnessofhypothetical socialscenarios(Pulcuetal.,2014).Similarly,weshowedthatremit- tedpatientsexhibitedattenuatedmedialprefrontalresponsestopos- itivesocialinteractionimages(Elliottetal.,2012).Inallcases,these neuronaldifferenceswereobservedintheabsenceofanydifferences inperformance.Onepossibleexplanationofthisisthatthesamebe- haviouraloutputisbeingachievedusingdifferentmechanisms,in