This research analyzes the influence of the differences in the occupational mobility of men and women on the gender division of the Russian labor market in 1985-2002. In section 2, we present the literature review on the issues of labor and especially occupational mobility and on the causes of gender segregation in the labor market. The results of empirical analysis of gender differences in occupational mobility are presented in section 5.

Section 6 contains the results of research into the impact of occupational mobility on changes in the gender wage gap. Our approach allows us to analyze the impact that occupational mobility has on the gender divide in the labor market.

OCCUPATIONAL GENDER STRUCTURE AND OCCUPATIONAL MOBILITY AT THE RUSSIAN LABOR MARKET

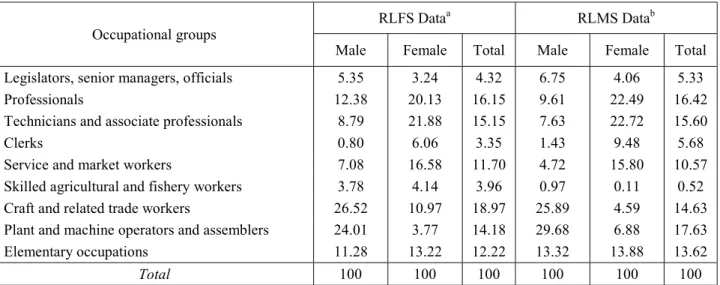

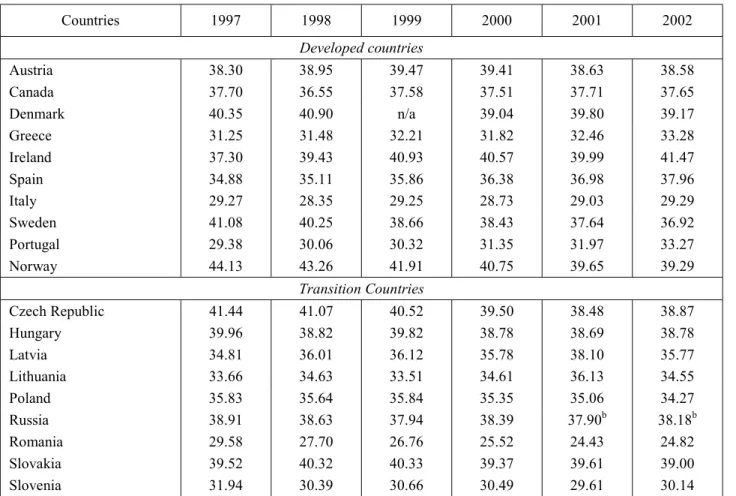

Transition to a market economy and changes of occupational gender structure Many researches state that the more detailed is the list of analyzed occupational groups, the higher

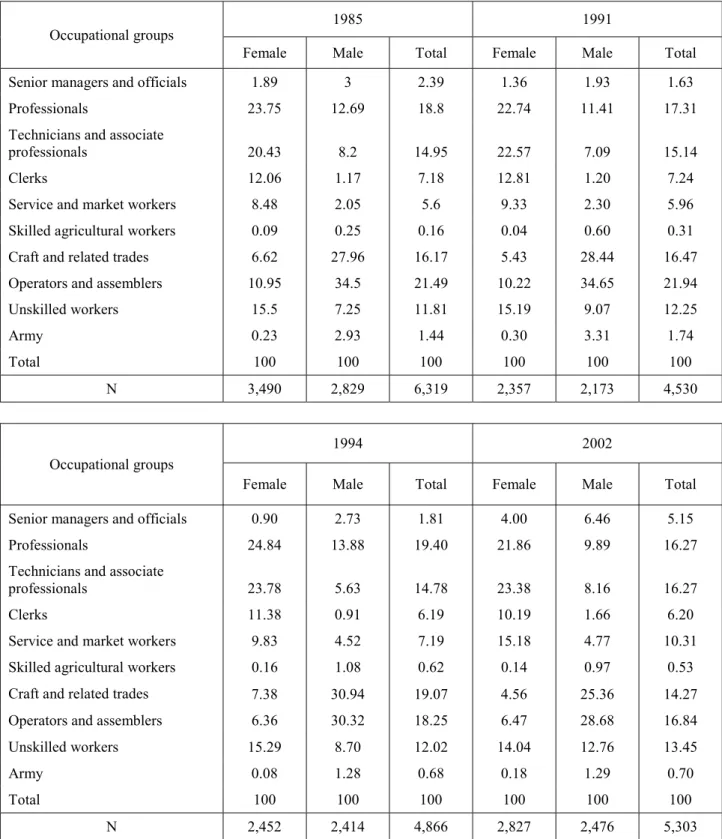

The changes reflect structural changes in the Russian economy of the period: a decrease in industrial production and an increase in the service sector. Also, there has been a significant decrease in the number of people of both sexes employed as operators and assemblers. It should also be mentioned the increase in the percentage of people employed as officials and senior managers, which is related to the increase in the number of companies (both new and formed as a result of the demolition of old ones).

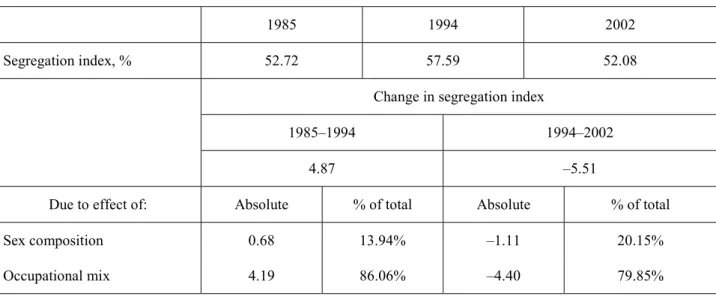

This was made possible by the increasing concentration in gender-dominated occupations, which was caused by the increase in the proportion of men in 'masculine' occupations and women in 'feminine' occupations (e.g. workers in metal, machinery and related occupations; professionals; models, salespeople and demonstrators). At the beginning of the period under review, there was a tendency to push women into 'male' occupations, increasing segregation.

Gender differences in magnitudes and directions of occupational mobility Economic reforms in Russia and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were accompanied by a

In the first case, this happened due to the increase in the concentration of employment in gender-dominated occupations, in the second - due to the decrease in concentration mainly as a result of the separation of "male" occupations. The replacement of workers of one gender by others within occupations can explain up to 20% of the changes in the overall index. During the reform period, the increase of men in "feminine" professions was positive from the point of view of reducing gender asymmetry.

As seen in Appendix Tables A7 and A8, while Russia was transitioning to a market economy, occupational mobility facilitated the widening of the gender gap. In addition, women were much more active in leaving "masculine" occupations, while the probability of men leaving "feminine" occupations was much lower. The "label change" effect is eliminated if we analyze changes in the spread of males and females across fixed occupations at the beginning of the period.

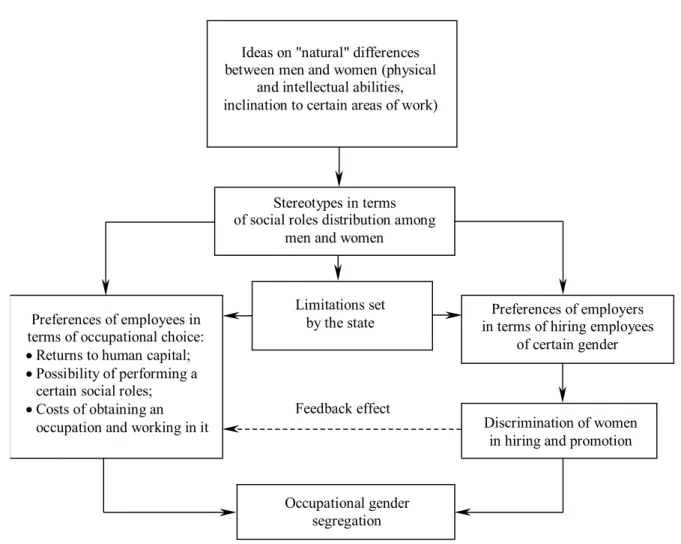

On the contrary, the probability of leaving professions that are atypical for the given gender is quite high. It is the individual's occupational orientation that largely determines in advance the extent of all returns from work. So it is possible to say that “mainly female” and “mainly male” professions have different characteristics.

It turned out that representatives of traditionally "male" professions can count on significantly higher average salaries. In general, the percentage of people working full-time in "female" occupations is lower than in the other two groups. Compared to other workers employed in "female" occupations, they are more likely to work for public enterprises, and the number of those working in the private sphere is very low.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN DETERMINANTS OF OCCUPATIONAL CHOICE 1. Research hypotheses

Results Table A12 of Appendix presents the results of the occupational mobility model estimation. The

This is due to the fact that the change of occupation implies additional time and financial costs which are something that families with small children do not have in abundance. In such a situation, expected benefits of mobility may be evaluated as lower than expected costs and the probability of changing occupations decreases. The hypotheses about negative interconnection between probability of mobility and age and tenure are also proven.

There seems to be no influence of gender role differences on the probability of occupational mobility. But the influence of occupational mobility on the level of gender segregation is not only expressed in the fact that employees of different sexes change occupations, but also in the occupations they choose while doing so. It is possible to mention the absence of statistically significant influence of variables, responsible for the distribution of social roles, on occupational mobility in general and choice of professions from different gender groups.

The probability of female occupational mobility and the choice of an atypical occupation for the respective gender is in such a case much lower than the probability of choosing an occupation from the "female" group. The size of alternative wages has a significant impact on women's occupational mobility: the higher it is, the greater the chances of them choosing "male" or "integrated" occupations. Significantly lower occupational mobility index for women in formulated models shows that the costs of changing occupations are higher for women than for men.

So it is possible to say that there is a certain inter-gender segmentation of behavioral models: those women who do not want or cannot reduce their household duties implement a passive behavior strategy without changing professions or move to "female" professions. The amount of population at the female worker's place of residence has a significant influence on the probability of choosing "male" or "integrated" occupation, which supports the suggestion that the absence of monopsony power and better developed service sector (compared to smaller settlements). ment) to expand the range of options for choosing a profession. OCCUPATIONAL MOBILITY AND CHANGES IN GENDER WAGES Salary is one of the most important elements that characterizes the return from work in a certain area for.

OCCUPATIONAL MOBILITY AND CHANGES IN GENDER WAGE GAP Wage is one of the most important elements characterizing the return from work at certain area for

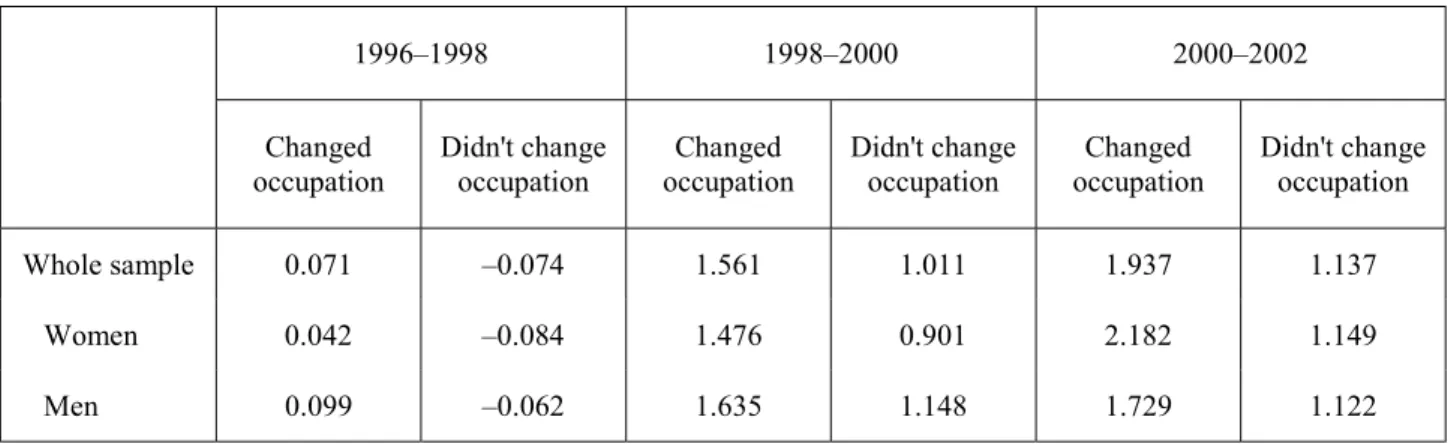

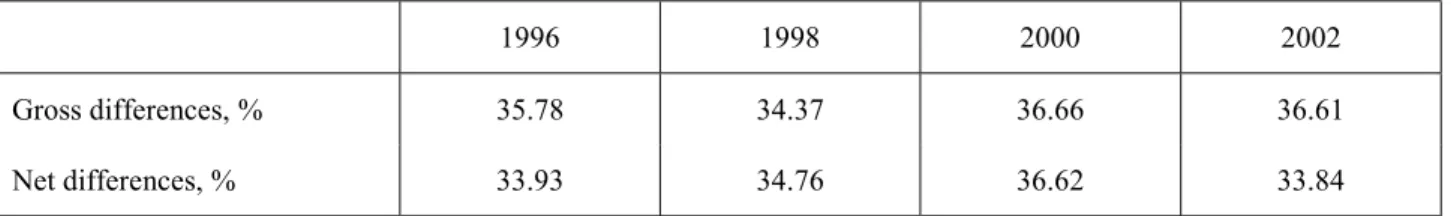

Therefore, due to the change of profession, women get the opportunity to compensate for the difference in wages with men, but only if the change in wages exceeds the growth of men's wages. As can be seen in Table 5, occupational mobility promotes the growth of wages of Russian employees. In the years 1996-1998, it was insignificant — around 7%, but when the wages of those who remained in the previous occupation decreased, this result also supported the hypothesis of a positive impact of mobility on the change in wages.

First, we estimate a traditional model of wage change model proposed in Section 3 . The estimation results presented in Table 15 of Appendix show that occupational mobility has a significant positive influence on the growth of wages for women. Both for men and women, occupational mobility has a positive influence on the change in wages.

In this model, the increase in the number of working hours has a positive effect on the growth of wages, but for men the coefficient is practically insignificant. Therefore, in order to ensure a positive increase in women's wages, it is necessary to reduce the burden on women in the household or to reduce rest. Unlike men, wage growth for women is positively related to education level.

It suggests that the level of accumulated human capital is important for the size of wages. In general, it is necessary to emphasize the fact that although occupational mobility supports the increase of wages for women, it currently does not have a significant impact on the level of the gender wage gap. In order to achieve wage increases, women must move into professions where representatives of their gender do not have quantitative dominance.

CONCLUSION The research conducted was aimed at defining and analyzing gender differences in occupational

To some extent this is related to the existence of occupational segregation in the Russian labor market. During the transition period, significant changes occurred in the occupational employment structure, which reflected the structural changes in the Russian economy of that period: decline in industrial production and growth of the service sector. Occupational mobility, both in the transition period and now, does not promote the reduction of gender segregation.

Econometric assessment of occupational mobility model did not show significant influence of gender role differences on the probability of occupational change by men and women. A significant difference is that for women higher income per family member increases the likelihood of occupational mobility and for men it is a deterrent to occupational mobility. In addition, factors such as work in the public sector, age and length of service have a negative effect on the probability of occupational mobility of both sexes.

The impact of employment mobility on the level of gender segregation is manifested not only through the employment changes of workers of different sexes, but also through the occupations they choose as a result of mobility. Econometric analysis of the probability of employees choosing a job atypical of their gender as a result of mobility demonstrated by dependence. In other words, the presence of wider opportunities for employment can facilitate the reduction of segregation through occupational mobility for women.

On the basis of the discovered differences in the size, directions and determinants of occupational mobility, it is possible to say that there is inter-gender segmentation of behavioral model: women who do not want or do not have a chance to reduce their household duties realize a passive strategy without changing professions or moving into "female" professions. To some extent, it is connected with the existence of occupational segregation in the Russian labor market: in order to achieve positive wage growth, women need to move into professions where representatives of their gender do not have quantitative dominance. At the same time, men moving into "female" occupations have a positive influence on wage growth.

Probabilities of occupational mobility between 3-occupation within each of the total group are in parentheses. Occupational mobility defined if the 3-digit occupational codes are different for the beginning and end of each period.