Doctoral School of Management Sciences and Business Administration

Anikó Csilla Csepregi

The Knowledge Sharing and Competences of Middle Managers

Doctoral (PhD) Dissertation

Supervisor: Dr. Lajos Szabó

Veszprém

2011

MIDDLE MANAGERS

Értekezés doktori (PhD) fokozat elnyerése érdekében

Írta:

Csepregi Anikó Csilla

Készült a Pannon Egyetem Gazdálkodás és Szervezéstudományok Doktori iskolája keretében

Témavezető: Dr. Szabó Lajos

Elfogadásra javaslom (igen / nem)

……….

(aláírás)

A jelölt a doktori szigorlaton …… %-ot ért el,

Az értekezést bírálóként elfogadásra javaslom:

Bíráló neve: …... …... igen /nem

……….

(aláírás) Bíráló neve: …... …...igen /nem

……….

(aláírás)

A jelölt az értekezés nyilvános vitáján …...%-ot ért el.

Veszprém, ……….

a Bíráló Bizottság elnöke

A doktori (PhD) oklevél minősítése…...

………

Az EDHT elnöke

KIVONAT ... 1

ABSTRACT ... 2

AUSZUG ... 2

1 INTRODUCTION ... 3

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 6

2.1 THE SPECIAL ROLE AND IMPORTANCE OF MIDDLE MANAGERS ... 6

2.2 THE IMPORTANCE OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 10

2.2.1 KNOWLEDGE ... 10

2.2.2 THE MACRO,MICRO AND INDIVIDUAL LEVELS OF KNOWLEDGE ... 15

2.2.3 KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 33

2.2.4 INFLUENCING FACTORS OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 40

2.2.5 BARRIERS TO KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 53

2.2.6 CONCLUSION OF THE IMPORTANCE OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 57

2.3 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF COMPETENCE AND COMPETENCY ... 59

2.3.1 APPROACHES,CLASSIFICATIONS, AND FEATURES OF COMPETENCE AND COMPETENCY ... 59

2.3.2 MODELS INVOLVING COMPETENCES AND COMPETENCIES ... 71

2.3.3 DIFFERENCE OF COMPETENCE MANAGEMENT AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT ... 77

2.3.4 CONCLUSION OF THE SIGNIFICANCE OF COMPETENCE AND COMPETENCY . 80 2.4 THE THEORETICAL BACKGROUND OF MY RESEARCH ... 81

3 EMPIRICAL STUDY ... 83

3.1 PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH ... 83

3.2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 83

3.3 RESEARCH MODEL ... 84

3.4 STRUCTURE OF THE RESEARCH ... 87

3.5 MATURITY OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 90

3.5.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 1 ... 90

3.5.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 1 ... 92

3.5.3 RESULTS ... 93

3.5.4 THESIS 1 ... 96

3.5.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 97

3.6 COMPETENCE FOUND IMPORTANT FOR KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 99

3.6.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 2 ... 100

3.6.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 2 ... 100

3.6.3 RESULTS ... 100

3.6.4 THESIS 2 ... 104

3.6.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 104

3.7.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 3 ... 107

3.7.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 3 ... 109

3.7.3 RESULTS ... 109

3.7.4 THESIS 3 ... 119

3.7.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 120

3.8 ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS INFLUENCING THE MATURITY OF KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 123

3.8.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 4 ... 123

3.8.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 4 ... 124

3.8.3 RESULTS ... 124

3.8.4 THESIS 4 ... 131

3.8.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 132

3.9 INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS INFLUENCING THE COMPETENCES FOUND IMPORTANT FOR KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 134

3.9.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 5 ... 134

3.9.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 5 ... 134

3.9.3 RESULTS ... 135

3.9.4 THESIS 5 ... 142

3.9.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 142

3.10 ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS INFLUENCING THE COMPETENCES FOUND IMPORTANT FOR KNOWLEDGE SHARING ... 144

3.10.1 AVAILABLE METHODS FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 6 ... 144

3.10.2 THE METHOD USED FOR TESTING HYPOTHESIS 6 ... 144

3.10.3 RESULTS ... 145

3.10.4 THESIS 6 ... 151

3.10.5 INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS ... 151

4 SUMMARY AND NOVELTY OF THE RESEARCH ... 153

5 COLLECTION OF THE THESES ... 161

6 PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE RESEARCH RESULTS ... 166

7 FUTURE RESEARCH PLANS ... 169

8 REFERENCES ... 170

9 APPENDIX ... 197

Table 1. Summary of the Studies Regarding Middle Managers ... 9

Table 2. Classification of Knowledge and its Meanings Before 2000 ... 13

Table 3. Classification of Knowledge and its Meanings Since 2000 ... 14

Table 4. Mapping the Pillars of the Knowledge Economy ... 16

Table 5. Ranking of Countries Regarding KEI (weighted by population) ... 17

Table 6. Principles of the Knowledge Organization ... 20

Table 7. Different Types of Organizational Knowledge ... 24

Table 8. Comparison of Individual Knowledge Types ... 27

Table 9. A Taxonomy of the Types of Knowledge Work ... 32

Table 10. Comparison of Knowledge Exchange, Knowledge Transfer, and Knowledge Sharing ... 33

Table 11. Classification of Knowledge Sharing ... 39

Table 12. Summary of the Research Regarding the Organizational Influencing Factors of Knowledge Sharing ... 52

Table 13. Summary of the Research Regarding the Behavioural Influencing Factors of Knowledge Sharing ... 53

Table 14. Barriers to Knowledge Sharing and Knowledge Management ... 54

Table 15. Classifying Boundaries ... 55

Table 16. Collection of the Classification of Barriers to Knowledge Sharing ... 56

Table 17. Differences in Definition of Competencies: the UK Versus the US Approach ... 61

Table 18. Competence Approaches in Terms of Related Perspectives, Basic Assumptions, Focus, and Dimensions of CM Transition... 62

Table 19. International Classification of Competences/Competencies ... 65

Table 20. Hungarian Classification of Competences ... 66

Table 21. Factors of Professional, Methodological and Social Competences ... 67

Table 22. Factors of Personal Competences ... 67

Table 23. Methods of Strategic Individual Competence (SIC) Development ... 69

Table 24. Competency Identification Methods ... 71

Table 25. Competency Dictionary ... 72

Table 26. Domains of Emotional Intelligence and Related Competencies ... 75

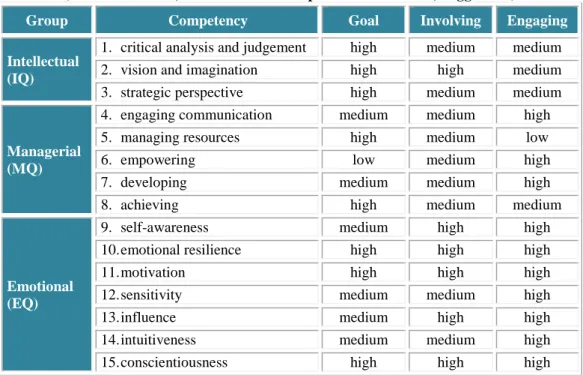

Table 27. Fifteen Leadership Competencies and the Competence Profiles of their Three Styles of Leadership ... 76

Table 28. Comparison of Knowledge Management and Competence Management Evolution ... 80

Table 29. The Average Number of Registered Employees at Medium- and Large-sized Enterprises between 2007 and 2010 ... 87

Table 30. Comparison of Cluster Analysis, Factor Analysis and Principal Component Analysis ... 91

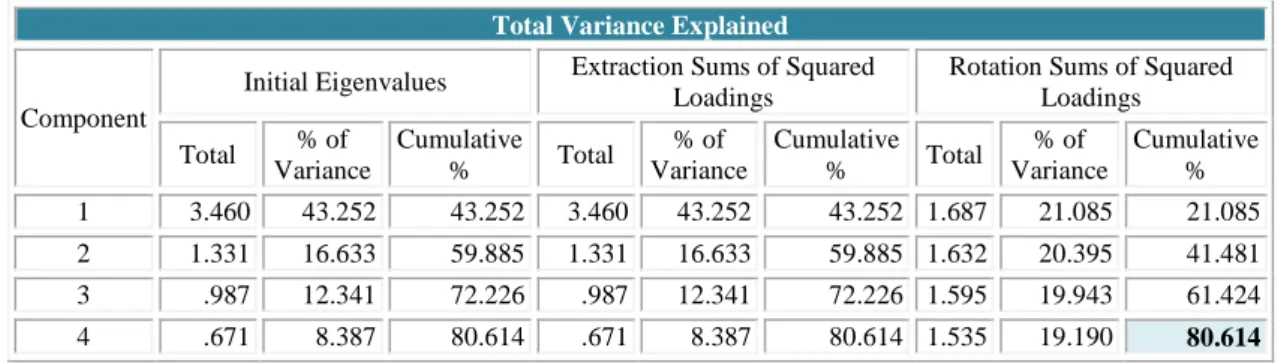

Table 32. The KMO and Bartlett Values of Maturity of Knowledge Sharing ... 93 Table 33. Total Variance Explained for Maturity of Knowledge Sharing Variables ... 94 Table 34. The Rotated Component Matrix Elements of Maturity of

Knowledge Sharing ... 95 Table 35. Components of Maturity of Knowledge Sharing and the Variables

Loaded on Them ... 96 Table 36. The KMO and Bartlett Values of Competence Found Important for

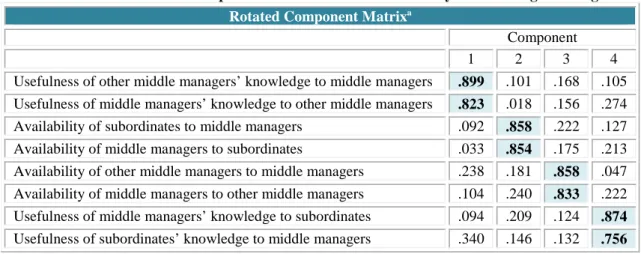

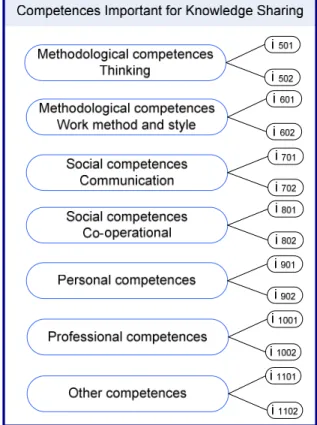

Knowledge Sharing ... 101 Table 37. Total Variance Explained for Competences Found Important for

Knowledge Sharing Variables ... 101 Table 38. The Rotated Component Matrix Elements of Competence Found

Important for Knowledge Sharing ... 102 Table 39. Principal Components and Variables of Competences Found

Important for Knowledge Sharing ... 103 Table 40. Comparison of the Available Methods for Testing Hypothesis 3 ... 108 Table 41. Comparison of the Available Methods for Testing Hypothesis 3

Regarding Benefits and Concerns ... 109 Table 42. The Most and the Least Favourable Classes within the Elements of

Maturity of Knowledge Sharing based on Individual Characteristics ... 112 Table 43. The ANOVA Results of the Groups of Availability among Middle

Managers and among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates

based on Individual Characteristics ... 114 Table 44. The Results of the Test of Homogeneity of Variance of the Groups of

Availability among Middle Managers and among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates based on Individual Characteristics ... 114 Table 45. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Availability among

Middle Managers ... 114 Table 46. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Availability among

the Middle Managers and their Subordinates ... 115 Table 47. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Usefulness of Knowledge

among Middle Managers based on Individual Characteristics ... 116 Table 48. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Usefulness of Knowledge

among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates based on

Individual Characteristics ... 117 Table 49. The Result of the Test of Homogeneity of Variance of the Groups of

Usefulness of Knowledge among the Middle Managers and their

Subordinates based on Individual Characteristics ... 118 Table 50. The Result of the Tamhane Test of the Groups of Usefulness of

Knowledge among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates ... 118 Table 51. Summary of the Results Regarding the Maturity of Knowledge Sharing

based on Individual Characteristics ... 119

Table 53. The ANOVA Results of the Groups of Availability among Middle Managers and among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates

based on Organizational Characteristics ... 128 Table 54. The Results of the Test of Homogeneity of Variance of the Groups of

Availability among Middle Managers and among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates based on Organizational Characteristics ... 128 Table 55. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Availability among

Middle Managers ... 128 Table 56. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Availability among the

Middle Managers and their Subordinates ... 129 Table 57. The ANOVA Result of the Group of Usefulness of Knowledge among

Middle Managers based on Organizational Characteristics ... 130 Table 58. Summary of the Results Regarding the Maturity of Knowledge Sharing

based on Organizational Characteristics ... 131 Table 59. The Most and the Least Favourable Classes within the Competence

Groups based on Individual Characteristics ... 136 Table 60. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Methodological Competences

Needed for Thinking based on Individual Characteristics ... 137 Table 61. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Social Competences Connected

with Communication Skills Regarding Individual Characteristics ... 139 Table 62. The Result of the Test of Homogeneity of Variance of the Groups of

Social Competences Connected with Communication Skills based on

Individual Characteristics ... 139 Table 63. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Social Competences

Connected with Communication Skills ... 139 Table 64. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Intercultural Competences

based on Individual Characteristics ... 140 Table 65. Summary of the Results Regarding the Competence Groups based on

Individual Characteristics ... 141 Table 66. The Most and the Least Favourable Classes within the Competence

Groups based on Organizational Characteristics ... 146 Table 67. The ANOVA Result of the Groups of Methodological Competences used

for Work Method and Style based on Organizational Characteristics ... 148 Table 68. The Result of the Test of Homogeneity of Variance of the Groups of

Methodological Competences used for Work Method and Style based

on Organizational Characteristics ... 148 Table 69. The Result of the LSD Test of the Groups of Methodological

Competences used for Work Method and Style ... 148 Table 70. The ANOVA Results of the Groups of Social Competences Connected

with Co-operational Skills based on Organizational Characteristics ... 149 Table 71. Summary of the Results Regarding the Competence Groups based on

Organizational Characteristics ... 150

Figure 1. Sectors of Manager’s Networks ... 9

Figure 2. The Development of Economies ... 18

Figure 3. Four Personnel Categories in Knowledge Organizations ... 21

Figure 4. Model of the Effective Knowledge Organization ... 22

Figure 5. The Classification of Organizations in Central and Eastern Europe ... 23

Figure 6. The Relationship between Organizational and Individual Knowledge ... 26

Figure 7. The Descriptors of the Knowledge Worker Concept ... 31

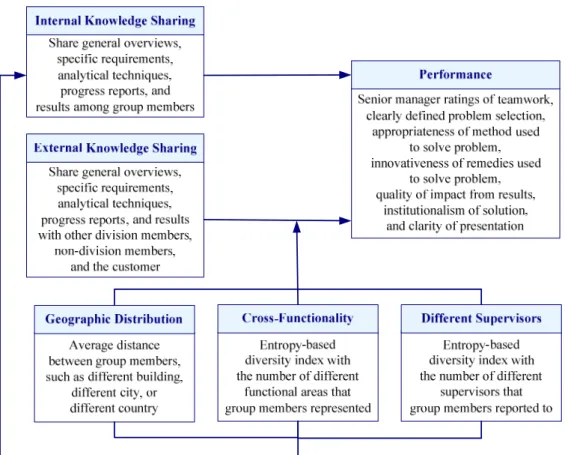

Figure 8. Model of Knowledge Sharing Within and Outside of Work Groups ... 41

Figure 9. A Framework Linking Organizational Knowledge Capabilities to Knowledge Sharing ... 42

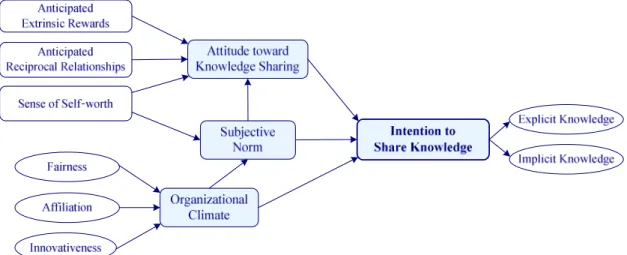

Figure 10. Proposed Knowledge Sharing Model ... 43

Figure 11. The Model of Knowledge Sharing of Organizational Units ... 45

Figure 12. The Model of Supporting and Hindering Factors of Knowledge Sharing .... 46

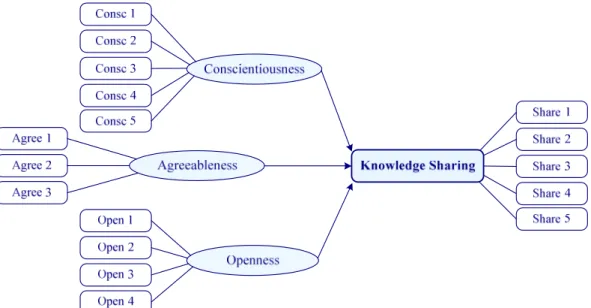

Figure 13. The Model of Personal Traits’ Effect on Knowledge Sharing ... 47

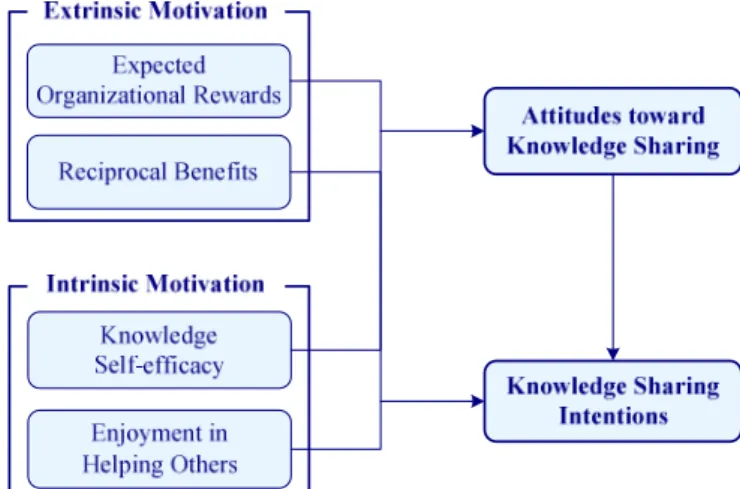

Figure 14. The Model of the Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivators on Knowledge Sharing ... 48

Figure 15. The Model of the Effect of Social Capital Factors on Knowledge Sharing .. 49

Figure 16. Full and Partial Knowledge Sharing and its Antecedents ... 50

Figure 17. Basic Cognitive Model of Knowledge Sharing Motivation ... 51

Figure 18. Typology of Competence ... 64

Figure 19. Holistic Model of Competence ... 64

Figure 20. An Integrated Model of Management Competencies at the Skill Level ... 73

Figure 21. The Competencies and the Leadership Roles in the Competing Values Framework ... 74

Figure 22. Model of Integrative Competence Management ... 78

Figure 23. Research Model ... 84

Figure 24. Structure of Research ... 89

Figure 25. Elements of Maturity of Knowledge Sharing under Investigation ... 90

Figure 26. Revealed Elements of Maturity of Knowledge Sharing ... 97

Figure 27. Elements of Competences Found Important for Knowledge Sharing under Investigation ... 100

Figure 28. Revealed Elements of Competences Found Important for Knowledge Sharing ... 104

Figure 29. Relations between Individual Characteristics and Maturity of Knowledge Sharing under Investigation ... 107

Figure 30. Classes Revealed within Availability among Middle Managers and among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates Elements based on Individual Characteristics ... 110

Elements based on Individual Characteristics ... 111 Figure 32. The Group Means of Availability among Middle Managers based on

Individual Characteristics ... 113 Figure 33. The Group Means of Availability among the Middle Managers and

their Subordinates based on Individual Characteristics ... 113 Figure 34. The Group Means of the Usefulness of Knowledge among Middle

Managers based on Individual Characteristics ... 116 Figure 35. The Group Means of Usefulness of Knowledge among the Middle

Managers and their Subordinates based on Individual Characteristics ... 117 Figure 36. Revealed Relationships between Individual Characteristics and

Maturity of Knowledge Sharing ... 119 Figure 37. Relations between Organizational Characteristics and Maturity of

Knowledge Sharing under Investigation ... 123 Figure 38. Classes Revealed within Availability among Middle Managers and

among the Middle Managers and their Subordinates Elements based

on Organizational Characteristics ... 124 Figure 39. Classes Revealed Within Usefulness of Knowledge among Middle

Managers Element based on Organizational Characteristics ... 125 Figure 40. The Group Means of Availability among Middle Managers based on

Organizational Characteristics ... 127 Figure 41. The Group Means of availability among the Middle Managers and their

Subordinates based on Organizational Characteristics ... 127 Figure 42. The Group Means of the Usefulness of Knowledge among Middle

Managers based on Organizational Characteristics ... 130 Figure 43. Revealed Relationships between Organizational Characteristics and

Maturity of Knowledge Sharing ... 131 Figure 44. Relations between Individual Characteristics and Competence Groups

under Investigation ... 134 Figure 45. Classes Revealed within Three Competence Groups based on

Individual Characteristics ... 135 Figure 46. The Group Means of Methodological Competences Needed for

Thinking based on Individual Characteristics ... 137 Figure 47. The Group Means of Social Competences Connected with

Communication Skills based on Individual Characteristics ... 138 Figure 48. The Group Means of Intercultural Competences based on Individual

Characteristics ... 140 Figure 49. The Revealed Relationships between Individual Characteristics and

Competence Groups ... 141 Figure 50. Relations between Organizational Characteristics and Competence

Groups under Investigation ... 144 Figure 51. Classes Revealed Within Two Competence Groups based on

Organizational Characteristics ... 145

Figure 53. The Group Means of Social Competences Connected with

Co-operational Skills based on Organizational Characteristics ... 149 Figure 54. Revealed Relationships between Organizational Characteristics and

Competence Groups ... 150 Figure 55. Hypotheses and the Research Model ... 154 Figure 56. Revealed Elements of the Research and their Revealed Relationships ... 157

1 Kivonat

Középvezetők Tudásmegosztása és Kompetenciái

A doktori értekezés a magyarországi közép- és nagyvállalatoknál dolgozó középvezetőket vizsgálja. Az értekezés fő célja a középvezetők tudásmegosztásának érettségét meghatározó tényezők feltárása, az által fontosnak tartott tudásmegosztást elősegítő kompetenciák csoportjainak azonosítása, valamint az egyéni és a szervezeti jellemzők ismeretében ezen tényezőkön, csoportokon belüli különbségek feltárása.

A szerző bemutatja és értékeli a tudásmegosztáshoz és kompetenciákhoz kapcsolódó szakirodalmat és az ezeken a területeken végzett korábbi kutatások eredményeit.

A kutatás empirikus felmérésre épül, amely során 2007 és 2010 között kérdőíves adatgyűjtésre került sor. Az összegyűjtött adatok kapcsán statisztikai és ökonometriai elemzések kerültek alkalmazására. Az ökonometriai elemzésekhez a szerző főkomponens analízist, döntési fát, varianciaanalízist és post hoc tesztet használ. Ezek felhasználásával meghatározásra kerülnek a középvezetők tudásmegosztásának érettségét leíró elemek, a középvezetők által fontosnak tartott tudásmegosztást elősegítő kompetenciák csoportjai, valamint az egyéni és szervezeti jellemzők tekintetében az ezeken az elemeken, csoportokon belül mutatkozó különbségek.

A kutatás eredménye azt mutatja, hogy a középvezetők tudásmegosztásának érettsége négy tényezővel írható le, a középvezetők által fontosnak tartott tudásmegosztást elősegítő kompetenciák pedig hét kompetenciacsoporttal. Ezen elemek között továbbá különbség mutatkozott az egyéni és szervezeti jellemzők tekintetében is.

A kutatás eredményei - a tudásmegosztás érettségét meghatározó tényezők, a tudásmegosztást elősegítő kompetenciacsoportok, valamint az egyéni és szervezeti jellemzők tekintetében mutatkozó különbségek - segítséget nyújthatnak a szervezeten belüli tudásmegosztó viselkedés fejlesztésében. A kutatáshoz kapcsolódó kérdőívnek más szervezeti szintekre, illetve országokra való kiterjesztésével a kapott eredmények további összehasonlítására is lehetőség nyílik.

2 Abstract

The Knowledge Sharing and Competences of Middle Managers

The author’s research focuses on middle managers who work at medium- and large-sized enterprises in Hungary. Regarding two hypotheses the author has chosen principal component analysis, concerning four hypotheses decision tree, analysis of variance and post hoc test have been applied. The results have revealed that middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing has been described by four elements, while the competence groups found important for knowledge sharing by seven competence groups. Difference has also been found regarding these elements on the basis of individual and organizational characteristics. The research results can be used to develop knowledge sharing behaviour within the organization or by extending the research to other organizational levels or countries these results can also be compared.

Auszug

Wissensverteilung und Kompetenzen des mittleren Managements

Die Verfasserin hat in ihrer Forschung die Führungskräfte in der mittleren Führungseben in ungarischen mittelständischen und Groβunternehmen untersucht. Bei zwei Hypothesen wurde Hauptkomponentenanalyse, bei weiteren vier Hypothesen Entscheidungsbaum, Varianzanalyse und Post-Hoc-Test verwendet. Die Forschung hat nachgewiesen, dass das

„Maturity“ der Wissensvermittlung beim mittleren Management durch vier Faktoren, und die vom mittleren Management als zentral eingeschätzte Wissensvermittlungskompetenzen durch sieben Kompetenzgruppen beschrieben werden können. Zwischen diesen Elementen ergaben weitere Unterschiede aufgrund individueller und organisatorischer Merkmale. Die Ergebnisse der Forschung können zur Entwicklung des verteilungsorientierten Verhaltens innerhalb der Organisation eingesetzt werden. Die Forschung kann auf andere organisatorische Ebene bzw. Länder ausgedehnt werden und demzufolge besteht die Möglichkeit zu einem Vergleich der Ergebnisse.

3 1 Introduction

The Importance of Middle Managers, their Knowledge Sharing and the Competences they Find Important for Knowledge Sharing

Nowadays knowledge is becoming an increasingly important factor of organizational competitiveness. Thus knowledge appears as an irreplaceable capital of organizations.

The way knowledge is shared within the organization is essential and central not only to the success of the organization where it takes place but also among those who share it, since those who take part in the knowledge sharing process also benefit from it.

Therefore the shared knowledge will help the competitiveness of the organization;

however losing the knowledge of employees may affect the competitiveness of these organizations negatively (Gergely, Szentes 2006). Furthermore, if employees realize the positive and useful consequence of knowledge sharing it will also continue to facilitate the sharing of knowledge within the organization.

One of the reasons why I have found the topic of investigating middle managers (managers working under top managers) interesting is that these employees can be found in the middle of their organizations. Thus they are related not only to their peers but also to the top-level and the first-level (operational level) management. Their special position within their organization also results in being a role model for the employees of their department or group, having a key position in vertical communication, being responsible for achieving business objectives by setting goals for their own department or group as well as, providing suggestions and feedback to the top management for helping the improvement of the organization.

Furthermore, middle managers play a key role in the knowledge sharing process as well.

It can be observed that during the process of knowledge sharing these middle managers’

role has to change from control to mentor and they also have to assist others (Pommier et al. 2000). However middle managers often resist the realization of such changes.

After building their careers and lives around the hierarchical pathways that exist within the organization, the appearance of a non-hierarchical work flow which does not require management behaviours concerning command-and-control may threaten them (Pommier et al. 2000). The fact regarding middle managers’ poor knowledge sharing and their resistance towards knowledge sharing should not be neglected since it may cause serious damages within the organization.

Knowledge cannot be shared efficiently without having the adequate competences. Thus it is also important to be aware of those competences that are necessary for knowledge sharing. From a large number of competences, those which are needed for knowledge sharing can be revealed with the help of middle managers, who will finally use them to share knowledge.

Being aware of the important position of middle managers within the organization, the resistance that may appear because of knowledge sharing and the competences that are important for knowledge sharing, show the difficulties and antinomy experienced in the role of middle managers.

4 Purpose of the Research

The purpose of this research is to:

• reveal those components that describe middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing who work at medium- and large-sized enterprises in Hungary;

• reveal those competence groups and competences that middle managers, who work at medium- and large-sized enterprises in Hungary, find important for knowledge sharing;

• discover which components of individual and organizational characteristics result in differences in the elements of these middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing;

• discover which components of individual and organizational characteristics result in differences within the competence groups these middle managers find important for knowledge sharing.

Research Questions

Regarding the purpose of this research I would like to answer the following questions:

Q1: With what kind of components can middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing who work at medium-and large-sized enterprises in Hungary be described?

Q2: Which competence groups are found important for sharing knowledge by middle managers who work at medium-and large-sized enterprises in Hungary?

Q3: How do individual and organizational characteristics influence middle managers’

maturity of knowledge sharing who work at medium-and large-sized enterprises in Hungary?

Q4: How do individual and organizational characteristics influence the competence groups middle managers, who work at medium-and large-sized enterprises in Hungary, find important for knowledge sharing?

The Significance and Relevance of the Research

The fact that no scientific research has been carried out in Hungary which measured middle managers working at medium- and large-sized enterprises concerning their knowledge sharing and the competence groups and competences they find important for knowledge sharing increases the importance of this research.

The results of this research could help not only the middle managers of medium- and large-sized enterprises in Hungary but also the top managers and the employees working under the middle manager as well.

The above mentioned beneficiaries of this research will be able to:

• measure their middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing after which they can learn how to develop their maturity of knowledge sharing;

• determine which individual and organizational characteristics affect middle managers’ maturity of knowledge sharing;

• define which competence groups and competences are important for knowledge sharing after which they can learn which competences need to be developed to share knowledge better;

• find out which individual and organizational characteristics influence the competences that middle managers find important for knowledge sharing.

5 The Structure of the Dissertation

The Introduction of the Dissertation is followed by the Theoretical Background which contains the literature overview of knowledge sharing and competences as well.

Regarding middle managers after presenting the various approaches of their role within the organization, previous studies investigating their relationship with other organizational members are introduced. Continuing the overview I highlight the different definitions, approaches, and classifications of knowledge. This is followed by the various levels of knowledge which consists of macro, micro and individual levels.

As a macro level investigation the features of the knowledge economy and as a micro level investigation the knowledge organization is introduced. This is followed by the overview of organizational knowledge existing within the organization and the individual knowledge that the employees of organizations have. After this the characteristics of knowledge workers, who represent the individual level of investigating knowledge, and the features of knowledge work are presented. The overview is continued with the introduction of knowledge sharing. After this, research and their results regarding the influencing factors of knowledge sharing conducted during the past few years are introduced. Since various barriers may hinder the sharing of knowledge if which are not revealed and eliminated can cause serious damages in the knowledge sharing process, thus the theoretical part will present the barriers to knowledge sharing revealed by previous researches. Certain competences are also needed to facilitate the sharing of knowledge. Therefore the theoretical overview of competences begins with the definitions, classifications and approaches of competences and the same features of a similar term called competencies as well. This is followed by the models of competences and competencies. After this the different perspectives of competence management are presented and those features are shown in which the management of competences and knowledge are different. The Theoretical Background ends with those theoretical and empirical parts of knowledge sharing and competences that contributed to my research.

The Empirical Study of the Dissertation starts with the justification regarding why this research investigates middle managers, their knowledge sharing and the competences they find important for knowledge sharing. Then I present the purpose of the research after which the research questions are introduced. This is followed by the presentation of the research model, and the components of the Research Model. After this the structure of the research is introduced including the way the data collection and the analysis are conducted, and showing the hypothesis revealed from the research model.

The remaining part of the Empirical Study contains the following steps: presenting the given hypothesis, the available methods for testing the hypothesis, the methods used for testing the hypothesis, the results, thesis and the interpretation of the results.

This is followed by the Summary and Novelty of the Research, the Collection of the Theses and the Practical Application of the Research Results. Finally the Future Research Plans are presented.

6 2 Theoretical Background

The theoretical background contains the literature review of middle managers, knowledge sharing and competences.

2.1 The Special Role and Importance of Middle Managers

While in the 1970s Chandler (1977) emphasised that middle managers’ job covers exclusively the supervision of the lower hierarchical level, now a large body of literature discusses their role in other fields. Despite the past 30 years, the term middle manager does not have a universally accepted definition. Bower (1986:297-298) emphasises that middle managers are the only ones within their organization “who are in a position to judge whether issues are being considered in the proper context”. From another point of view Uyterhoeven (1989:136) argues that a middle manager is someone “who is responsible for a particular business unit at the intermediate level of the corporate hierarchy”. Ireland (1992) provides a more concrete definition regarding middle managers and describes them as employees working between an organization’s first-level and top-level managers. Furthermore their jobs contain the integration of “the intentions of top-level managers with the day-to-day operational realities experienced by first-level managers” (Ireland 1992:18). Regarding their position in the organization Staehle and Schirmer (1992:70) emphasise that middle managers are “employees who have at least two hierarchical levels under them and all staff employees with responsibility for managing personnel”.

According to Schlesinger and Oshry (1984) middle managers have to fulfil two major integrating tasks which are the investigation of top management and workforce, and their own integration across functional lines. Furthermore they believe that there is a connection between their commitment towards higher level of integration and the potential regarding the effectiveness of individuals and organizations (Schlesinger, Oshry 1984). Based on this Schlesinger and Oshry (1984) differentiated several possible integration levels containing the following categories: no integration, information sharing, assimilating information, mutual consultation, joint planning and strategizing, and power bloc.

The literature of middle managers contains several other tasks the managers need to fulfil which are the followings:

• balancing the demands and interests of those organizational member who are above and blow them (Schlesinger, Oshry 1984);

• becoming adept at the integration of “hard” technical skills and “soft” skills (Barnes et al 2001);

• possessing people skills since they have to work closely with other people within and outside the organization (Sayles 1993);

• balancing short- and long-term business demands (Schlesinger, Oshry 1984);

• being close enough to actual operations (Sayles 1993).

In the following section previous studies investigating middle managers are reviewed.

These studies can be divided into two categories. One of them examined the middle manager - top manager relationship, while the other dealt with the middle manager - subordinate relation.

7 The Relationship of Middle and Top Managers

The concept of compressive management regarding middle and top managers was introduced by Nonaka (1988). Nonaka’s concept of compressive management recognized a key role for middle management in information development as follows:

the “top management creates a vision or dream, and middle management creates and implements concrete concepts to solve and transcend the contradictions arising from the gaps between what exists at the moment and what management hopes to create”

(Nonaka 1988:9). In other words, this means that an overall theory is created by the top management, whilst a middle-range theory is created and tested empirically within the organizational framework by the middle management. The Honda “City” development was used to illustrate “middle-up-down” management which was a process that resolved the arising discrepancy between the top management’s visionary and also abstract concepts and the concept based on experience from the lower organizational level (Nonaka 1988). The top management had a dream to “create an original car of high energy and resource efficiency” (Nonaka 1988:18) and to achieve this dream, it was brought down to the level of middle management who created and realized a more concrete concept with the use of self-organizing group.

An increasing body of literature has also highlighted middle managers’ essential role in the strategy process which process has resulted in several positive outcomes, such as:

• increase in middle managers satisfaction (Westley 1990);

• middle managers’ improvement in organizational performance (Wooldridge, Floyd 1990);

• middle managers’ stronger attachment to their job and to their organization (Oswald et al. 1994).

Reaching strategic consensus at the middle management level also plays a vital role in the process of strategy making. More precisely Pappas et al. (2003) emphasise that middle managers’ knowledge of not only the internal capabilities but also the external environment of their organization besides their position in the management structure has significant effect on the realization of strategic consensus. Furthermore, if these middle managers have minimal strategic knowledge of these internal and external factors, they can build consensus in areas that can affect the organization’s long-term performance as well (Pappas et al. 2003).

Not only the strategic performance but also the competitive position of the organization contributes positively to the upward influence behaviours of middle managers (Floyd, Wooldridge 1994; Dutton et al. 1997). In addition the performance could be improved if the top management understands what motivates middle managers to engage in issue selling after which the middle managers can be engaged in the issue selling process (Dutton et al. 1997). Issue selling is a critical activity during the early stages of organizational decision making when the identification of issues first takes place (Dutton, Ashford 1993). The initiation of issue selling is highly effected by impression management, which is a social psychological process during which people aim to create and maintain desired perceptions of themselves through the eyes of others (Schlenker 1980; Schneider 1981). The impression management literature furthermore suggests that middle managers are active and purposive in managing these impressions, but if the right issue selling tactics are not available for middle managers to create the ‘right impression’ they are more likely not to initiate issue selling (Dutton et al. 1997).

8

Schilit’s (1987) study differentiated a number of characteristics of middle managers’

involvement in the strategy process more precisely in the strategic planning and decision making process. The study showed that upward influence activity was much more widespread in low risk/return types of strategic decisions and middle managers were more involved in the implementation than in the formulation of strategic decisions.

Regarding the influence in strategic decision middle managers were tend to use rational or persuasive arguments to convince top managers of their point of view. Furthermore, concerning success and failure in influencing their superiors the middle managers most often ascribed their failure to external causes while their success to internal causes.

Although, as it can be seen above, a large number of literature regarding middle managers highlights middle managers’ crucial influence on the strategy process, top managers “often fail to make distinctions about the variety of contributions made by middle managers, and, in particular, overlook the possibility that middle managers play strategic roles” (Floyd, Wooldridge 1994:48).

Middle Managers and their Relationships with their Subordinates

Crouch and Yetton (1988) revealed that depending on the level of subordinate task performance middle managers maintain distinct relationships with their subordinates.

Their (Crouch, Yetton 1988) study showed that those subordinates who perform at a high level have high task contact with their managers and also experience friendly behaviour. While those who have low performance rating have not only low task contact with their managers but also these managers’ behaviour is experience to be less friendly.

Regarding the relationship of middle managers and their subordinates two kinds of conflict can emerge which are pure emotional conflict and mixed conflicts (Xin, Peller 2003). The latter is a combination of task and emotional conflicts. The result of Xin’s and Peller’s (2003) survey showed that pure emotional conflict can impair managers evaluations thus subordinates dealing with such conflicts may perceive that certain leadership abilities are lacking by their supervisors. As a result of the negative feelings characterizing these conflicts, subordinates may consider it difficult to respect their supervisors and give them favourable evaluation (Xin, Peller 2003). On the other hand mixed vertical conflicts also have negative associations with the perceptions of supervisors’ leadership behaviour regarding emotional support but no relationship occurred with the perception of creativity encouragement (Xin, Peller 2003).

By paying equal attention to the point of view of leaders and subordinates the study of Glasø and Einarsen (2006) has explored those emotions, moods and emotion-laden judgements that are experienced by subordinates during interaction. As a result, four similar emotional factors were detected which were labelled as recognition, frustration, violation and uncertainty. Furthermore strong correlation was revealed between these factors and subordinates’ job satisfaction and the quality experienced in interaction with superiors.

After reviewing previous studies examining middle managers Table 1 summarises them according to the authors who investigated middle managers, who the middle managers were related to, and what the subject of the examination was.

9

Table 1. Summary of the Studies Regarding Middle Managers

Authors Perspective of relationship Subject of investigation Schilit

(1987)

Top Manager- Middle Manager

strategic planning and decision-making Nonaka

(1988) „compressive management”

Dutton, Ashford

(1993, 1997) issue selling

Pappas, Flaherty

(2003) strategic consensus

Crouch, Yetton (1988)

Middle Manager-Subordinates

task performance - social contact Xin, Pelled

(2003) emotional and task conflicts

Glasø, Einarsen

(2006) emotional responses, quality of relationship

However in the following Figure of Kaplan (1984), in which the networks of managers are presented, it can see that middle managers are not only in vertical relationships with others, they are also in lateral relationships

Figure 1. Sectors of Manager’s Networks (Kaplan 1984:38)

I found a similar concept in the statement of Uyterhoeven (1989) as well. According to Uyterhoeven (1989:137) „the middle manager wears three hats in fulfilling the general management role” and these are being a superior, a subordinate and an equal. This is why they also have to manage relationships in several directions: upwards when they

10

take orders; downwards when they give orders; and laterally when they relate to peers.

Regarding my research it is important to highlight the fact that one of its novelties is that it focuses not only on the vertical but also on the lateral relationships of middle managers and investigates their roles and relationships in these directions. Thus the main direction of my research contains these middle managers’ downward vertical and the horizontal lateral relationships.

2.2 The Importance of Knowledge Sharing

First the different definitions, approaches, classifications of knowledge are presented.

Then the various levels of knowledge containing knowledge economy and knowledge organization are introduced, which are followed by the overview of organizational knowledge and individual knowledge. After this the characteristics of knowledge workers and the features of knowledge work are also presented as the final (individual) level of knowledge. Continuing the overview knowledge sharing, the influencing factors and the various barriers to knowledge sharing are also introduced. This section ends with summarizing those previous theoretical and empirical researches of knowledge and knowledge sharing which contributed to my research that investigates the knowledge sharing of middle managers.

2.2.1 Knowledge

The traditional production factors in the traditional economy contained resources that were easily measured and quantified, as labour, land, or tangible capital (DiStefano et al. 2004) but after a while changes took place (Burton-Jones 1999). In spite of these changes, in Drucker’s (1992:95) opinion these traditional “factors of production” have not disappeared but have become secondary and so knowledge has become not only a new factor of production but “the primary resource for individuals and for the economy overall”. This statement results in the recognition of the fact that knowledge has become important in sustaining the competitive advantage of an organization as well. Since what an organization knows makes it possible to differentiate itself from others (Davenport, Prusak 1998). Besides organizational competitiveness where efficient creation, dissemination, and application of knowledge are essential, Roberts (2001) has also recognized that it has been significant at national levels as well.

Defining Knowledge

To understand how knowledge can become such an important element of organizational competitiveness, I find it important to define what knowledge is. Thus in this subpart my aim is to present knowledge from different approaches.

I found seven different but sometimes overlapping approaches from the literature, which according to my grouping are:

• information as a central element of knowledge;

• action also appearing as an important element of knowledge;

• appearance of rules extending the elements of knowledge;

• where knowledge can be found;

• knowledge appearing as a product;

• process point of view of knowledge;

• broad definitions of knowledge containing several features.

11 Information as a Central Element of Knowledge

Brooking (1999:5) puts knowledge as “organized information together with understanding of what it means”. Knowledge is considered by Géró (2000:106) as

“information based on structured data” that is understood and thought through by someone. Knowledge is also utilized in a surrounding that is defined by the given person’s experiences and store of learning and finally is shared with others (Géró 2000).

Knowledge is created according to Liebeskind (1996) if the validity of information is established through tests of proof. Furthermore, Hajós and Bittner (2006) view knowledge as containing not only information but ability and skills as well. According to them (Hajós, Bittner 2006:28) during ability “data can be acquired, utilized and converted into useful information” while skills, will and form of behaviour “make people able to think, interpret and act in an innovative manner”.

Action Also Appearing as an Important Element of Knowledge

Information as a significant component of knowledge is also emphasized by Davenport et al. (1999) but it is used for actions and decisions. According to their definition knowledge “is a high value form of information that is ready to apply to decisions and actions” (Davenport et al. 1999:89). Leonard-Barton and Sensiper (1998) and Demarest (1997) emphasise the actionable feature of information when determining knowledge.

Knowledge is “information that is relevant, actionable, and based at least partially on experience” by Leonard-Barton and Sensiper (1998:113) and is “the actionable information embodied in the set of work practices, theories-in-action, skills, equipment, processes and heuristic of firm’s employee” by Demarest (1997:374). The action perspective of knowledge is stressed by Sveiby (1997) as well, but by having the necessary capacity to behave so. Knowledge is defined by him (Sveiby 1997:37) as “the capacity to act”. Nooteboom (2001:3) also considers knowledge as an act but during which information is interpreted into a cognitive framework. Beside the characteristics of action, decision is also stressed by Fahey and Prusak (1998:269) and in their point of view both are inseparable from knowledge that is defined by them as “imbuing data and information with decision- and action-relevant meaning”.

Appearance of Rules Extending the Elements of Knowledge

Ruggles (1997), Den Hertog and Huizenga (2000) extended the definition of knowledge by including rules as an important element of it. While according to Ruggles (1997:2) knowledge is “a fluid mix of contextual information, values, experiences, and rules”, Den Hertog and Huizenga (2000:332) stress knowledge as being “a collection of rules and information to fulfil a specific function”.

Where Knowledge can be Found

Davenport and Prusak (1998:5), when offering their so-called “working definition” of knowledge, emphasise that knowledge “originates and is applied in the minds of knowers” and extend this statement by mentioning that “In organizations, it often becomes embedded not only in documents or repositories but also in organizational routines, processes, practices, and norms.”. De Long and Fahey (2000:114) also emphasise knowledge as being “a resource that is always located in an individual or a collective or embedded in a routine or process”.

12 Knowledge Appearing as a Product

De Long and Fahey (2000:114) also consider knowledge as “a product of human reflection and experience”. Opposite to them, Pentland (1995:5) notices knowledge as being “the product of an ongoing set of practices embedded in the social and physical structures of the organizations”.

Process Point of View of Knowledge

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) have a unique definition of knowledge. They (Nonaka, Takeuchi 1995:58) view knowledge from a process point of view and consider it as a

“dynamic human process of justifying personal beliefs toward the ‘truth’ ”.

Broad Definitions of Knowledge Containing Several Features

According to Davenport and Prusak (1998:5) knowledge is “broader, deeper, and richer than data or information” and they offer the following “working definition” of this term:

"knowledge is a fluid mix of framed experience, values, contextual information, and expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information”. Spek and Spijervet (1997:36) also collected several features to determine knowledge which is thus “the whole set of insights, experiences, and procedures which are considered correct and true and which therefore guide the thoughts, behavior, and communication of people” and it is “always applicable in several situations and over a relatively long period of time”.

Barely any of the above mentioned scholars have emphasised the importance and use of knowledge regarding knowledge sharing, which I missed in connection with the overview of the definitions of knowledge. Thus I have found it favourable that Géró (2000) has been an exception. In my opinion knowledge can be considered important and valuable when it is used and shared. Furthermore since my research focuses on middle managers’ knowledge sharing I find it also important to have a definition of knowledge that contains the knowledge sharing aspect as well.

My definition of knowledge is inspired by those approaches that have stressed the broad definitions of knowledge containing several features (such as the definitions of Davenport, Prusak and Spek, Spijervet). Furthermore those approaches that have emphasised where knowledge can be found (such as the definitions of Davenport, Prusak and De Long, Fahey) have also helped me in creating my own knowledge definition. Therefore my research defines knowledge as the whole of information, experience, routines, practices that can be connected with people, can be found in the mind of a person or in electronic or paper documents, databases and can be broadened during sharing that occurs between the knowledge sender(s) and the knowledge receiver(s).

Classifying Knowledge

The recognition of the different types of knowledge is necessary in revealing its potential contribution to the organization’s performance and in assigning the appropriate channels to facilitate the transmission of knowledge (Pemberton, Stonehouse, 2000). Table 2 and 3 contain the different classifications of knowledge.

13

Table 2. Classification of Knowledge and its Meanings Before 2000 Classification of

knowledge Meaning

Sackmann (1992)

dictionary knowledge commonly held descriptions used in a particular organization,

"what" of situations and their content directory knowledge

commonly held practices,

chains of events and their cause-and-effect relationships,

"how" of things and events, their processes recipe knowledge

based on judgments,

prescriptions for repair and improvement strategies,

"shoulds" and recommends of certain actions

axiomatic knowledge

reasons and explanations of the final causes perceived to underlie a particular event,

"why" things and events happen, why a particular problem emerged, or why people are promoted in a given organization

Lundvall, Johnson (1994)

know-what knowledge about facts

know-why knowledge of principles and laws of motion in nature, in the human mind and in the society

know-how knowledge about skills, the capability to do something know-who

information about who knows what, and who knows to do what,

a mix of different kinds of skills

Nonaka, Takeuchi (1995)

explicit knowledge formal and systematic, easy to communicate and share

tacit knowledge

highly personal, hard to formalize, difficult to communicate to others,

deeply rooted in individual’s action, experience, ideals, values, or emotions

Blackler (1995)

embrained knowledge depends on conceptual skills and cognitive abilities embodied knowledge emphasises practical thinking,

action oriented

encultured knowledge emphasises meanings, shared understandings arising form socialisation and acculturation

embedded knowledge emphasises the work of systemic routines encoded knowledge embedded in signs and symbols

Ruggles (1997)

process knowledge how-to

(similarly generated, codified, transferred as the other two) catalog knowledge what is

(similarly generated, codified, transferred as the other two) experiential

knowledge

what was

(similarly generated, codified, transferred as the other two) Probst

(1998)

individual knowledge relies on creativity and on systematic problem solving collective knowledge involves the learning dynamics of teams

14

Table 3. Classification of Knowledge and its Meanings Since 2000 Classification of

knowledge Meaning

De Long, Fahey (2000)

human knowledge what individuals know or know how to do something structural knowledge embedded in the systems, processes, tools and routines of

an organization

social knowledge largely tacit, shared by the member of the group, developed as the result of working together Becerra-

Fernandez et al.

(2004)

general knowledge held by a large number of individuals, can easily be transferred across individuals

specific knowledge possessed by a very limited numbers of individuals, not easily transferred

Christensen (2007)

professional knowledge is created and shared within communities-of-practices either inside or across organizational barriers

coordination knowledge makes each employee knowledgeable of how and when he is supposed to apply knowledge

object-based knowledge knowledge about an object that passes along the organization’s production-line

know-who

knowledge about who knows what, or who is supposed to perform activities that influence other’s organizational activities

Zhang et al.

(2008)

individual knowledge related to the process, that is the elementary cell for knowledge creation, storage and usage

team knowledge

the accumulated knowledge capital of the team is more than the sum of knowledge of each member, creates a valuable result

organization knowledge to form a complete organization it possesses own unique structure, function partition and procedure

Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2004) created a framework with which the economic value of knowledge can be clarified. Furthermore in their point of view knowledge can be grouped into general knowledge and specific knowledge (Becerra-Fernandez et al.

2004). General knowledge is held by a large number of individuals and can easily be transferred across them (Becerra-Fernandez et al. 2004). Example of general knowledge is the standard operation procedures. Knowledge possessed by a very limited numbers of individuals and which is not easily transferred is called specific knowledge that can be technical or contextual. While technically specific knowledge is considered as deep knowledge about a specific area and consist of knowledge of tools and techniques for addressing problems in that area, contextually specific knowledge includes knowledge of particular circumstances of place and time in which the work is performed (Becerra- Fernandez et al. 2004).

Reviewing knowledge it can be seen that the classification of knowledge is diverse and it is hard to find common features. There are some exceptions, since some of the classifications consider knowledge as mainly connected to the knower, who can be an individual or a group, as something that depends upon different features, and as something that is used within the organization for some kind of purpose or to achieve something.

Since knowledge can appear on different levels, such as macro, micro, and individual levels, in the next section these levels and their features will be reviewed.

15

2.2.2 The Macro, Micro and Individual Levels of Knowledge

In this part of the theoretical overview as a macro level investigation of knowledge the main features of knowledge economy, and the knowledge organization as a micro level investigation of the knowledge is presented. After this the review of organizational knowledge that exists within the organization and individual knowledge owned by organizational employees is introduced. This is followed by the characteristics of knowledge workers who represent the individual level of investigating knowledge and also by the features of knowledge work.

2.2.2.1 From Knowledge Economy to Knowledge-driven Economy

In March 2000, the EU Heads of States and Governments agreed to make the EU "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-driven economy by 2010" (Lisbon Agenda).

This intention has been mutually reinforced in the 3 priorities of Europe 2020 (smart growth, sustainable growth and inclusive growth). The smart growth priority also contains the previously mentioned development of an economy based on knowledge and extends it with the feature of innovation as well (Europe 2020). Thus it is obvious that Hungary as a member of the EU should also fulfil the requirements of the knowledge-driven economy.

Carayannis and von Zedtwitz (2005) used a spectrum of feasible stages of development to review the economies of nations and related them to different development pathways.

The spectrum of economic development stages contains subsistence, emerging, development, transitioning, and developed (Carayannis, von Zedtwitz 2005).

Carayannis and von Zedtwitz (2005) distinguished four economy types which are subsistence-based economy, commodity-based economy, knowledge-based economy, and knowledge-driven economy. These economy types differ in many aspects (Carayannis, von Zedtwitz 2005; Carayannis et al. 2006). While in subsistence-based economies survival is the main issue, the dominant means and goals of economic production and exchange are commodities in commodity-based economies; furthermore barter-based economies also develop up to some transitioning economies here.

Knowledge-based economies and knowledge-driven economies also differ in several characteristics (Carayannis, von Zedtwitz 2005; Carayannis et al. 2006).

Knowledge Economy

The economy, that is driven by globalization, rapidly changing information and communication technology is characterized by Tapscott (1997:8) as follows: “it is widely accepted that the developed world is changing from an industrial economy based on steel, automobiles, and roads to a new economy built on silicon, computers, and networks” and this “new (digital) economy is a knowledge economy”. According to Jashapara (2011:9) the knowledge economy is “not a new economy with new laws […]

it is an economy driven by knowledge intangibles rather than psysical capital, natural resources or low-skilled labour”. In order to maintain market position, to develop new products or technologies in this new economy, organizations need to exploit, develop, collect and share organizational knowledge effectively and efficiently (Gaál et al. 2008).

16

In knowledge-based economies knowledge emerges as one of the key means and goals of economic production and exchange, additionally as one of the key economic resources with high degree of utilization and sharing as well (Carayannis, von Zedtwitz 2005; Carayannis et al. 2006). Here technological innovation and economic learning are considered to be the key modalities of the economic development and growth (Carayannis, von Zedtwitz 2005; Carayannis et al. 2006).

Difference has been made between knowledge economy and knowledge-based economy by Cooke and Leydesdorff (2006). Knowledge economy is considered by the authors (Cooke, Leydesdorff 2006) as the older one of the two concepts, since according to the authors it had its origin in the 1950s and it focused on the composition of the labour force. Furthermore by adding „the structural aspects of technological trajectories and regimes from a systems perspective” the term, knowledge-based economy has appeared (Cooke, Leydesdorff 2006:5). However since the terms knowledge economy and knowledge-based economy are often used synonymously, in the followings I will not make distinction between these two terms either.

To be able to reveal other hidden features of knowledge economy I found it relevant to mention its comparison with the traditional economy and information society as well.

The traditional economy is characterised by emphasising the importance of resources which can be easily measured and quantified, while knowledge economy stresses intangible resources as tacit knowledge, knowledge generation, and capacities for knowledge sharing or continuous learning (DiStefano et al. 2004). When comparing the knowledge economy with the information society on the one hand, the skills of people and the value of the training are presumed to be the dividing line between them. On the other hand education is also treated differently: it is just the “admission ticket” in the knowledge economy, while it guarantees a career in the information society (Huysman, Wit 2002).

To represent the overall preparedness of countries towards the knowledge economy the World Bank has developed an aggregate index called Knowledge Economy Index (KEI). It summarizes the country’s performance on indicators that correspond to the four pillars of the knowledge economy and it is constructed as the simple average of these indicators (World Bank 2007, 2008). The pillars and the indicators can be found in Table 4.

Table 4. Mapping the Pillars of the Knowledge Economy (based on World Bank 2008:3)

pillar economic and institutional regime

education and skill of population

information

infrastructure innovation system

indicator

• tariff and non tariff barriers

• regulatory quality

• rule of law

• adult literacy rate

• gross secondary enrolment rate

• gross tertiary enrolment rate

• telephones per 1000 people

• computers per 1000 people

• internet users per 1000 people

• royalty payment and receipts

• technical journal articles per million people

• patents granted to nationals by US Patent and Trademark Office per million people