Introduction

Over the last few years, the Short Food Supply Chain (SFSC), a term coined by Marsden et al. (2002) and legally defined by EU Regulation 1305/13, has received consider- able attention from academics as a direct consequence of the increasing interest of consumers towards this alternative sale channel, which is able to offer greater guarantees in terms of food safety and the healthiness of products (Migliore et al., 2015). There is a widespread belief that the SFSC is able to make the agricultural sector more sustainable.

However, the environmental dimension of the sustain- able character of the SFSC has recently raised some doubts regarding its contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions during the transportation phase (Schmitt et al., 2017). Indeed, if on the one hand, as compared to the Mass Food Supply Chain, the reduction in travelled km of food products contributes to making the chain more sustainable, on the other hand, the extent to which farmers’ frequent participation in local or regional markets is making an effective contribution of CO2 reduction at an overall local level has increasingly become a matter for reflection among academics. Some scholars are attempting to investigate this environmental impact by theoretically referring to the food miles concept, initially linked to the overall food supply chain (Paxton, 1994), thus from the cultivation phase final distribution, a concept more recently linked much more explicitly to carbon accounting and the climate change debate (Schmitt et al., 2017; Galati et al., 2016; Kissinger, 2012; Coley et al., 2011; Kemp et al., 2010; Smith and Smith, 2000). This, of course, plays its part in the recent scientific debates on climate change with particular atten- tion on the transport system impact both of goods and peo- ple. In this domain, starting with the EU Directive 2014/94/

EU on alternative fuels, in 2016 the EU Commission set a new target for road transport according to which within 2050 a reduction of 60% of CO2 emissions can be achieved.

A challenge that is aimed to ensure overall sustainability but at the same time responding to the transport forecasts

according to which within 2050 transport will increase by 42%. Accordingly, if the transport growth cannot be stopped one can instead reduce the related CO2 emissions, by changing/converting the transport means power systems to greener ones. In this context, a more promising option is the Electric Vehicle (EV) (both hybrid and 100% versions currently available in the market), and towards which the main National, Regional and Local policies around Europe are investing (from public transport means to private and commercial final use).

In line with these recent trends, this study explores the intention of entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC to intro- duce EVs inside their business, with a view of overall sus- tainability. In particular, in order to understand which factors affect this behaviour a case study approach has been chosen (Yin, 1984), applying a conceptual framework based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP). The firms selected represent the universe of those participating in the farmer’s markets of the city of Palermo, in Sicily (Italy). To the best of our knowledge, the present exploratory study, is the first one aimed at investi- gating the behaviour of entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC against the opportunities to introduce an EV for the freight transports to reach farmer’s market.

Short Food Supply Chain

At the base of the SFSC there is the creation of a trust relationship between producers and consumers, usually iden- tifiable in a face-to-face interaction, thus allowing a direct relationship that in the global FSC is totally absent. Accord- ing to the definition of short food supply chains developed by Marsden et al. (2002), SFSCs have the capacity to “re- socialise” or “re-spatialise” food, thus allowing consumers to make value-judgements about foods. Authors make clear that “it is not the number of times a product is handled or the distance over which it is ultimately transported which is nec- essarily critical, but the fact that the product reaches the con- Marcella GIACOMARRA*, Antonio TULONE*, Maria CRESCIMANNO* and Antonino GALATI*

Electric mobility in the Sicilian short food supply chain

This paper is the first study to explore the intention of entrepreneurs operating in the Short Food Supply Chain to adopt electric mobility inside their business. For this purpose, a case study approach was chosen, employing a questionnaire based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the New Ecological Paradigm to investigate the determinants affecting this intentional behaviour. The empirical analysis has been carried out in the city of Palermo (Italy), involving 42 entrepreneurs who participate in farmer’s markets. Results show that entrepreneurs with higher levels of intention to introduce sustainable means of trans- port, such as electric vehicles, are the most concerned about the environment and the delicate balance of natural ecosystems.

Moreover, the more frequently local farmers participate in local markets, the higher is their intention to adopt electric vehicles for their business. The preliminary results here discussed enrich the existing literature and provide interesting insights for Short Food Supply Chain entrepreneurs and policy makers, paving the way for future research into this topic.

Keywords: local food supply chain; electric vehicles; farmer’s market; theory of planned behaviour; new ecological paradigm JEL classifications: Q13, Q18

* Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Viale delle Scienze, Building 4, Palermo 90128, Italy. Corresponding author:

antonio.tulone@unipa.it.

Received: 9 April 2019, Revised: 10 July 2019, Accepted: 15 July 2019.

sumer embedded with information”, enabling the consumer to confidently make connections and associations with the place/space of production, “and potentially the values of the people involved and the production methods employed”

(Marsden et al., 2002).

The scientific literature has subsequently shed light upon further factors and implications attributable to the SFSC and directly linked to sustainability goals (economic, social and environmental impacts). As for the SFSC’s economic impact, authors concur in attributing rural development and economic regeneration to these models (DuPuis and Good- man, 2005; Renting et al., 2003), as well as noting that they stimulate local employment opportunities (Roininen et al., 2006), with multiplier effects (Henneberry et al., 2009), and increased income for producers (Pearson et al., 2011; Fea- gan and Morris, 2009). In social terms, several investigations have showed the ethical dimension as characterising the SFSC. In this sense, Ilbery and Kneafsey (1998) found that producers often act as “profit sufficers” rather than “profit maximisers”, putting at the top of producer’s intention their contribution to the well-being of the community, rather than aspiring to capital maximisation (Jarosz, 2008).

As for the environmental impacts evaluation linked to SFSC, several contrasting opinions are currently under dis- cussion at the scientific level. Indeed, if on the one hand schol- ars highlight the positive impacts of SFSC in terms of food miles and carbon footprint reduction (Van Hauwermeiren et al., 2007), other authors support a thesis according to which when in the SFSC local products are stored and pur- chased out of season, these products may have a greater carbon footprint than non-local goods (Edwards-Jones, 2010; Cowell and Parkinson, 2003). In this regard, the food mile literature opens interesting debates. Originally con- ceptualised in the nineties (Paxton, 1994), this concept was first linked to the overall food production process (from the cultivation phase to distribution). More recently, how- ever, food miles have been linked much more explicitly, and in some cases solely, to carbon accounting and the cli- mate change debate (Schmitt et al., 2017; Kissinger, 2012;

Coley et al., 2011; Kemp et al., 2010; Smith and Smith, 2000). This change has led to a shift in the focus of the food miles argument away from sustainable agriculture production systems per se to food distribution and retailing and, in particular, to the GHG linked to transport. In this regard, Coley et al. (2011), looking at the carbon emissions of several delivery systems as compared to direct sales for vegetable box schemes, found that customers who have to drive more than 6.7 km in a round trip to buy their organic vegetables have higher levels of emissions when compared to the emissions involved in the system used by the large distributors. Ideas regarding the environmental benefits of local food in terms of the reduction in food miles and GHGs need to be rethought and better reformulated, as stressed by Schmitt et al. (2017), which support the argument that despite this, locally processed food products can be defined as more sustainable, not because of their having a lower carbon footprint, but rather in respect of localness criteria (e.g. identity, know-how, size and governance) instead of distance concerns. Given the relevance of consumer’s role in contributing to the spreading of more sustainable food

purchasing practices, a need for further work on improv- ing overall awareness about that is also suggested by Kemp et al. (2010), whose results suggest that the “food miles”

argument has not had great influence on the behaviour of supermarket shoppers.

Electric vehicles adoption

The substantial emission reductions necessary to achieve climate change reduction targets require, among others, a de- carbonization of transport. EVs are seen as a viable and very promising alternative, especially if electricity is generated in a clean manner (Egbue et al., 2017). To date, no scholars have ever attempted to assess the propensity of entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC in introducing EVs into their business activities. The majority of works carried out in this last dec- ade, in fact, has been addressed to assess the main drivers for the uptake of EV, mainly referring to private traditional car owners and early adopters, with the aim to investigate cus- tomer behaviours, intentions and preferences about support schemes (Santos and Davies, 2019; Ramos-Real et al., 2018;

Quak et al., 2016; Rezvani et al., 2015; Bunce et al., 2014;

Plötz et al., 2014). Santos and Davies (2019), resuming the opinions of 189 respondents, represented by stakeholders and experts, found that 75% of respondents, state that the development of charging infrastructure is on the top of the priorities for a mass EVs deployment, followed by purchase subsidies (68%), pilot/trial/demonstrations (66%) and tax incentives (65%). Moreover, other scholars focused the attention on highlighting social, economic and demographic characteristics of customers (Rezvani et al., 2015; Plötz et al., 2014), also attempting analysis on using electrically powered vehicles in urban freight transport from a carrier’s perspective (Quak et al., 2016).

As Ramos-Real et al. (2018) suggest, geographic dimen- sion of the area concerned by EVs introduction is also a relevant factor, together with the necessity that end users effectively know technical data on EVs so as to be able to do an aware choice. Authors, studying the feasibility of EVs introduction in the Canary Islands, underline how the small size of one’s territory dictates driver mobility routines, as the short average travel distance reduces the effects of range anxiety. Furthermore, authors underline that willingness to pay for an EV purchase is positively correlated with some factors, among others, education attainment and strong envi- ronmental concern (Ramos-Real et al., 2018). As for range anxiety limit, which is defined as being one of the main prob- lems facing drivers interested in buying EVs, a recent study carried out in UK found that the initial range anxiety would fade over time due to knowledge and confidence developed through driving for an extensive period of time (Bunce et al., 2014). Nevertheless, scholars point out how other technical shortcomings should be appropriately considered to allow for an effective spread of the use of the technology, since range anxiety represents a strong limitation in the adoption of EV most particularly where longer distances need to be travelled, but also that EVs’ high purchase costs add a further obstacle to a wider and profitable diffusion (Morganti and Browne, 2018).

Conceptual framework

With the aim to investigate the propensity of entrepre- neurs operating in the SFSC to introduce EVs inside their business, we started from the consideration that the intention to adopt a specific behaviour depends on farmers’ attitudes towards a given behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, 1991). However, in those cases where a link with sustainability considerations exists, other authors add the role played by environmental concerns (Dun- lap et al., 2000). Therefore, the case study proposed here has been explored by employing a conceptual framework based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the New Ecological Paradigm.

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980), is based on the premise that individuals make logical and reasoned decisions to engage in specific behaviours, by evaluating the information available to them.

According to the TPB model, an individual’s intention to perform a behaviour is a function of that individual’s attitude toward the behaviour, social norms and perceived behavioural control. Attitude towards the behaviour (ATT) is conceived by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) as an “individu- al’s positive or negative evaluation of the performance of a particular behaviour”. A person, who believes that valuable positive outcomes would result from performing the behav- iour, will have a positive attitude toward it. According to the TPB model, it must be said that the more favourable attitude toward a behaviour, the more possibility that the individual will perform that certain behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). The sec- ond dimension, named Social Norm (SN) is a social pressure exerted on an individual to engage in a particular behaviour (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Indeed, individuals intend to perform a behaviour when they feel that the people who are important for them confirm that behaviour (Shin and Hancer, 2016). Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) consists in the ease or difficulty of a particular behavioural performance as it is perceived by individuals (Ajzen, 1991). This component emphasises the extent to which that an individual perceives a behaviour to be under his/her volitional control (Fielding et al., 2005). Behavioural control is related to beliefs about the presence of factors that may further or hinder the perfor- mance of behaviour (Ajzen, 2002; Ajzen and Madden, 1986).

The above mentioned dimensions, affect the Intention (INT) which is an “individual readiness to perform a given behav- iour” and is recognised as the motivation which is necessary for engagement in a particular behaviour. The intention is the most substantial predictor of behaviour and is assumed to be an immediate antecedent of this (Ajzen, 2002).

A review of literature shows that the TPB has long been successfully used to investigate a wide variety of farmers’

intentions such as: adoption of innovations and technologies (Adnan et al., 2019), sustainable practices (Zeweld et al., 2017; Menozzi et al., 2015; Fielding et al., 2008), adaptation to climate change (Arunrat et al., 2017; Dang et al., 2014),

engagement in pro-environmental activities (Van Dijk et al., 2016). Despite the general usefulness of the TPB to iden- tify and understand different behaviours of farmers, some scholars have attempted to enhance the predictive power of the TPB model, by including additional constructs Rezaei et al., (2018), who extend the TPB model by including the two constructs of moral norms and knowledge, have rec- ognized an increased robustness and explanatory power of the proposed framework in predicting farmer’s inten- tions towards engaging in farm food safety enhancements.

Positive remarks relating to the robustness of an extended TPB have been also expressed by Giampietri et al. (2018).

Authors, adding the trust construct to the original TPB, agree on the greater performance of the model in predicting inter- viewees’ intention to purchase food in SFSCs. Employing different constructs allowed Menozzi et al. (2015) to bet- ter investigate consumers’ intentions to purchase traceable chicken and honey in France and Italy. Adding new variables (e.g. habits, trust, past behaviour and socio-demographics) to the original TPB has demonstrated how an extended TPB model can be of relevant importance in better predicting behaviours in two different countries. Adnan et al. (2019) concluded their work highlighting that if paddy farmers have more concern towards the environment, they will be more attracted towards adopting sustainable agricultural practices.

Results have been achieved thanks to the employment, also in this case, of an extended TPB model, which includes new variables linked to external and economic factors.

To date, far too little attention has been paid to extend- ing the TPB model by incorporating additional constructs mainly pertaining to the environmental sphere, with a par- ticular reference on NEP. To this we add that, despite the growing literature on farmer’s behaviours through the appli- cation of TPB, no studies have paid attention to the behav- iours of entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC as regards their intention to utilise electric mobility for managing freight transport.

New Ecological Paradigm

In investigating the environmental attitude of an individ- ual, the field of environmental psychology can be of relevant support. This last term refers to a specific tendency expressed by evaluating a particular object related to the environment with some degree of favour or disfavour (Kaiser et al., 2011).

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale (Dunlap et al., 2000), is considered as the most widely used environmental attitude instrument today. Originally proposed in 1978 by Dunlap and Van Liere (1978), this theory has been revised in 2000 (Dunlap et al., 2000). The NEP scale consists of 15 Likert-scale items, which are intended to measure five core components of individuals’ environmental concern: (1) lim- its to economic growth, (2) anti-anthropocentrism; (3) the fragility of nature’s balance; (4) human exceptionalism; and (5) the possibility of potentially catastrophic environmental changes or eco-crises affecting people (Dunlap et al., 2000).

The NEP has been used in previous studies to investigate consumer attitudes about the risks of genetically modified food (Hall and Moran, 2006), to stress how environmental

concern affects marine species conservation (Pienaar et al., 2015), to study pro-environmental orientation differences between people living in city areas and rural districts (Beren- guer et al., 2005).

For what in our knowledge, this is the first time that the NEP scale is used to assess the environmental orientations of entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC.

Methodology

In order to explore the intention of entrepreneurs oper- ating in the Short Food Supply Chain to adopt the electric mobility inside their business a case study approach was chosen (Yin, 1984). According to Yin (1984:23) the case study research method is “an empirical inquiry that inves- tigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life con- text; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evi- dence are used”. Yin (1984) recognizes three categories of case study approaches, namely exploratory, descriptive and explanatory. Exploratory case studies, the type we selected, set out to explore any phenomenon in the data which serves as a point of interest to the researcher. In the exploratory case study, general questions and small scale data collection are necessary to open up the door for further examination of the phenomenon observed. Unlike in experiments, the contex- tual conditions are not delineated and/or controlled, but part of the investigation. Typical for case study research is non- random sampling; there is no sample that represents a larger population. Contrary to quantitative logic, the case is chosen, because the case is of interest.

The present case study is part of an European project, titled EnerNETMob, and co-funded by the INTERREG Mediterranean Programme 2014/2020. Within this scope, the research group has been charged with understanding the contexts and political background, as well as opinions and intentions specifically held by farmers operating in the local SFSC. The decision to consider the SFSC rather than other segments is linked to the intrinsic propensity of this business model to adopt more sustainable practices in almost all its production and distribution phases as the extant literature, previously presented, has widely showed.

To investigate the entrepreneurial propensity to intro- duce EVs inside their business, firstly authors worked on the political and legal background characterising the Sicil- ian Region, with a specific focus on the main Provinces (in terms of economic activities and populations). Regional laws, decrees, Regional Action Plans and other relevant documents have been thus studied so as to better understand the context inside which explore farmers’ intentions. After identifying and contacting the main farmers’ associations managing SFSC markets, an introductory presentation to the associations’ managers was arranged with the aim of collect- ing their general opinions on our area of research as well as other technical information relating to associated farmers, their production methods, and the frequency of their partici- pation in local markets. An empirical analysis was carried out in the city of Palermo (Sicily, Italy) during March 2019, involving local farmers’ associations managing farmer’s

markets in the homonym Province, among which Coldiretti group, currently leading the label “Campagna Amica”, the Association “PianetaMercati”, the Association “Fattorie Sociali” and the Association “Contadini in Villa”. The city of Palermo was chosen for two reasons. It was selected first of all for reasons relating to the project scope, and secondly because, in recent years, the farmer’s markets there hosted have achieved a great degree of diffusion and broad accept- ance on the part of consumers (Garrone, 2017; Pianeta Mer- cati, 2019). In terms of actors, or more specifically SFSC farmers, according to data provided by Spesa dal Contadino (2019), there are 119 farms participating in the Sicilian farm- er’s markets, and the majority of these (59 farms) operate in the city of Palermo and its Province. At first, face-to-face interviews were conducted with the main representatives of the Sicilian agricultural associations, such as the President of Fattorie Sociali, the Vice President of the Italian Association of Organic Agriculture in Sicily, and members of Coldiretti Sicily management’s board.

After the first exploratory phase, a questionnaire for SFSC’ farmers was developed and organised in four sections.

In the first section, main data on firm characteristics was col- lected, covering information such as principal production, headquarters, and production methods. The second section collected socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, including specifications about eventual sons/grandchild in their family nucleus and membership to environmental asso- ciations. The third section contained specific questions aimed at gathering knowledge about the transport system character- istics of each sampled firms as well as questions attempting to quantify yearly distances travelled to reach selling points.

The behaviours towards the EV introduction into their busi- ness has been measured through section four, which included a set of questions based on the TPB, appropriately modified according to the research field. The last section, the fifth, has been devoted to acquire data on individuals’ environmental concern using questions based on the NEP scale. Questions pertaining to section 4 and 5 included a five-point Likert scale. As for the TPB, the questionnaire items were defined, taking into account Ajzen’s conceptual and methodological considerations for constructing a TPB questionnaire (Ajzen, 1991) and the previous works carried out in similar field where a 5-point response format has been used (Giampieri et al., 2018; Rezaei et al., 2018; Adnan et al., 2019; Arunrat et al., 2017). Meanwhile, for the NEP scale, the selection of a five-point Likert scale has been decided upon following the results of a meta-analysis on works employing NEP scales, executed by Hawcroft and Milfont (2010), who highlighted that all studies, like the Dunlap et al. (2000) one, used a Lik- ert scale and that 83.45% of the sample employed one with five-point response format. As a consequence, respondents were asked to specify their opinion respecting each item, using a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 as follows:

1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=neither agree nor disa- gree; 4=agree; and 5=strongly agree.

Giving the innovative nature of the research question and hence of the sample to be involved in order to gain initial primary data regarding this particular SFSC issue, follow- ing Yin (1984), we involved in our case study’s survey the overall world of the SFSC farmers of Palermo. Indeed, in

I would like to introduce e-mobility in my farm in the future.

Intention to introduce EVs

The resources in my farm are sufficient for the distribution of food products through e-mobility.

The introduction of e-mobility in my farm is quite simple and I can easily manage it.

The adoption of e-mobility in my farm depends exclusively on me.

Perceived Behavioural Control

Other farmers I know believe that e-mobility is an important issue and they are engaged in its introduction to their farms.

The people, whose I appreciate opinions, will approve my choice to introduce e-mobility into my farm.

More and more farmers will adopt sustainable practices in the future linked to distribution through the use of EVs.

Social Norms

The introduction of e-mobility in my farm is a good and wise choice.

The introduction of e-mobility in my farm will contribute to increasing the green image of my company.

The awareness and knowledge of e-mobility must be increased among farmers as a tool to reduce CO2 emissions.

Attitudes

4.19 3.79 3.67

3.33 3.07 2.26

3.17 2.71 2.48

3.52

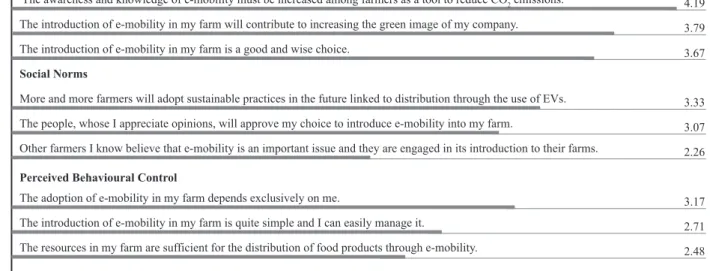

Figure 1: Drivers about the introduction of electric mobility in the farm based on the TPB (range 1 to 5).

Source: own composition

tribution points. Concerning the battery’s limit for an aver- age journey, interviewees did not consider this aspect to be a great concern, thereby highlighting that a good number of SFSC farmers usually travel distances inside the optimal range covered by the current batteries available on the mar- ket. Nevertheless, they expect that the more public infra- structures are reinforced (through the increase in the number of charging points), as well as being planned according to the real needs of operators, the more this limit will be overcome, above all by those entrepreneurs who travel more km than the average.

These first results, achieved through interviews with stakeholders, allowed us to better integrate the questionnaire subsequently employed with SFSC entrepreneurs and thanks to which relevant results have been achieved. In particu- lar, analysis of the questionnaires reveals at first an overall farmers’ propensity towards shifting from carbon transport systems to electrical ones as evidenced, in Figure 1, by the greater number of interviewees who are convinced they will introduce electric mobility in the future for the distribution of agro-food products (3.52). The intention to introduce electric mobility in the short chain appear mainly linked to the shared opinion among the interviewees that this choice could contribute, on the one hand, to reducing CO2 emis- sions (4.19) and, on the other hand, to improve the image of the company on the market (3.79). Respondents believe that the strong orientation towards sustainable choices will also concern the introduction of EVs (3.33), and this is in line with the awareness that corporate choices are shared by people (3.07). However, what emerges from the study is a lower awareness, among the interviewees, of the ability to control this new transport system, as emerges from the scores obtained, which are all around the average. Further- more, results show that, on average, firm’s internal resources are not sufficient for an efficient management of this alterna- tive transport system if implemented (2.48).

the overall Province 59 farmers were regularly registered in farmers’ associations managing local markets and partici- pated in one or more of the numerous local markets. Out of a total of 59 questionnaires administered to farmers for compi- lation, 42 were considered correctly completed and then used for the analysis. Questionnaires were administered directly in loco, with researchers visiting farmers’ markets. All the farms have headquarters in rural areas, around 20-100 km distant from Palermo city.

Results

The results presented here are the findings of a cross- validatory triangulation of data generated by the different sources employed during the case study analysis, namely documentation analysis, interviews with relevant stakehold- ers operating in the Sicilian SFSC and an empirical survey conducted among the entrepreneurs active in the farmer’s markets of the Province of Palermo.

For those representatives of the Sicilian agricultural associations interviewed in the first phase of the analysis, an overall agreement was found in the form of a general awareness that in the food transport sector things should also move towards more sustainable options. Even if EVs are recognized as one of the most promising cleaner modes of transport, some concerns arise at first regarding the actual high costs of vehicles, which in turn could represent a major burden for SFSC entrepreneurs over a brief period. Moreo- ver, interviewees showed an overall optimism towards pro- gress being made in regional infrastructural development currently. In this regard, where plans for the deployment of charging points are concerned, interviewees suggest great attention also needs to be paid to the positioning of these points outside urban areas, in particular on provincial roads, which are the routes SFSC farmers usually take to reach dis-

Empirical evidences demonstrate that the environmen- tal proactive behaviour of entrepreneurs, associated to the introduction of EVs, is related to the different facets of the possible ecological concerns about the nature, as reported in Figure 2, according to which respondents agree on average on the five NEP ecological visions. In particular, based on mean responses to each of the ecological visions considered, it seems that respondents tend towards a good enough pro- ecological worldview, proved by the positive agreement for

“Possibility of an eco-crisis” (4.21 out of five) and “Fragility of nature’ balance” (3.59 out of five). In this way, results high- light a great awareness among respondents of the importance of protecting natural resources, which are exploited by human beings, causing disastrous consequences. An opinion further confirmed by the strong awareness of the fact that humans are seriously abusing the environment. Furthermore, the presence of an overall pro-ecological opinion among respondents is also showed by the shared disagreement about “Anti-anthro- pocentrism” (2.94) and “Rejection of exceptionalism” (2.21).

In order to better understand the behaviour of entrepre- neurs participating in the SFSC and their propensity to intro- duce the electric mobility, respondents were ordered based on their intention to introduce EVs in their business, from the lesser to the most inclined. This propensity was there-

fore related to the average value derived from the TPB and NEP factors. Results highlight that individuals with a high propensity to move the carbon transport system to the elec- trical one show a more positive attitude towards that behav- iour, completed by positive scores in the effects from social norms, and a better Perceived Behavioural Control. Further- more, they also show particular concern about the scarcity of resources, the possible ecological catastrophes that can derive from an inappropriate exploitation of the environment and its resources, and the delicate balance of nature.

In addition, an interesting fact arising from the study is that entrepreneurs that show a greater willingness to intro- duce electric mobility in the SFCS are the same who more frequently participate in the farmers’ markets, since their corporate headquarters is located near these markets.

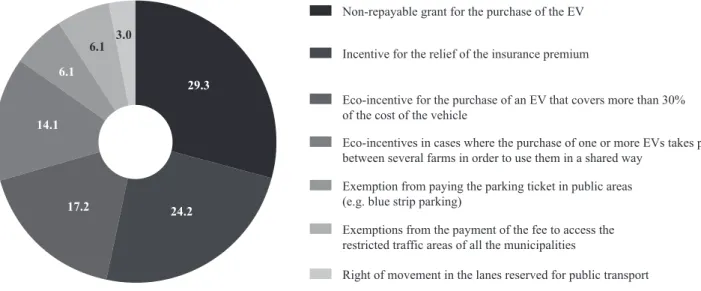

This study also wanted to highlight the potential meas- ures desirable for farmers to encourage the spread of electric mobility. Findings suggest that measures aimed at cover- ing direct costs related to electric mobility (non-repayable grants, incentives for the relief of the insurance premium, and eco-incentives for the purchase of EVs) are the most pre- ferred by entrepreneurs. Conversely, support tools targeted at achieving a reduction in the costs associated with EV use are less appreciated by interviewees.

Anti-Exemptionalism Anti-Anthropocentrism Fragility of nature' balance Possibility of an eco-crisis

Reality of limits to growth 4.60

4.21 3.59 2.94 2.21 Figure 2: Ecological visions according to the New Ecological Paradigm Scale (range 1 to 5).

Source: own composition.

1 2 3 4 5

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42

Figure 3: Trend of propensity to introduce EVs considering the factors of the TPB and NEP.

Source: own composition.

Discussion

The present case study presents preliminary results on the behaviour of farmers operating in the SFSC against the opportunity to introduce EVs for the freight transports to reach local farmers’ markets. This exploratory analysis is part of the activities provided by the EnerNETMob project, and addressed to the spread of the EV in EU bigger cities of Mediterranean area. Results, on the one hand represent important insights for the pilot action anticipated by the project and which include the positioning of EVs charging points in strategic points of the cities concerned, among them the Sicilian main ones, while on the other hand they may stimulate future research into this topic, supporting scholars in investigating in significant detail the SFSC’s farmer behaviour toward the transition of a more sustainable transport system.

The study of the official documents currently in force in Italy and Sicily allowed us to understand, at first, the legisla- tive and political context on which the case study rests. Data collected gave us a picture of a country in which EV policies and above all infrastructural investments have been launched and widely supported by a public-private partnership cre- ated for this purpose. With particular attention to Sicily, the infrastructural EV charging system is ready to function as proved by the national infrastructure plan for the recharge of vehicles powered by electricity (PNIRE), approved by the Government in 2014. Following the PNIRE input, the Sicilian Regional Authority, in 2017 approved the Regional Plan for Infrastructure and Mobility (PIIM), which includes detailed measures for ensuring the spread of electric mobility all across the island.

The main interesting and noteworthy findings of the pre- sent work, due to their managerial and political implications, originate from the profiling of interviewees we did according to the high or low levels of intention displayed. High social norms scores are present in the group with higher intention towards introducing an EV in their business, suggest how

Right of movement in the lanes reserved for public transport Exemptions from the payment of the fee to access the restricted traffic areas of all the municipalities

Exemption from paying the parking ticket in public areas (e.g. blue strip parking)

Eco-incentives in cases where the purchase of one or more EVs takes place between several farms in order to use them in a shared way

Eco-incentive for the purchase of an EV that covers more than 30%

of the cost of the vehicle

Incentive for the relief of the insurance premium Non-repayable grant for the purchase of the EV

29.3

17.2 24.2 14.1

6.1

6.1 3.0

Figure 4: Approval ratings about support measures to encourage the spread of electric mobility.

Source: own composition.

being in the presence of people with higher environmental concern, as well as the social context they belong to play a relevant role in pushing entrepreneurs towards more and more sustainable practices. This result indicates that cultural and social contexts are relevant factors when a farmer intends to opt for a radical transformation in their business. These cultural aspects should in turn be taken into careful account when investigating a change of this type. The higher value of PBC in this group, compared to the score of the overall sam- ple, suggests how social norms and environmental aware- ness make the vital difference in relation to the possibility of introducing greener modes of transport. A similar correlation as well as importance to cultural and social contexts has been found by Giampieri et al. (2018) where, analysing through TPB the intention of consumers to buying in SFSC, found that the more consumers’ attitudes are positive toward SFSC and the more the people who are important for them approve the behaviour, the more the PBC increases.

However, the entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC who are most concerned about the environment and the delicate balance of natural ecosystems are those who have the high- est intention to reduce their environmental impact through sustainable means of transport, such as electrically powered vehicles. This evidence is also supported by the literature on EVs, according to which Ramos-Real et al. (2018) found that early adopters are, among other features, the one with high levels of environmental concern. To this we add that by taking into account the social and geographical context from which this group belong to, i.e. rural areas, our findings are in line with Berenguer et al. (2015) who, applying the NEP scale, found that people living in the rural context display more attitudes of environmental responsibility and greater consistency on expressing behavioural intentions compatible with the protection of the environment compared to people living in city areas.

The greater propensity to introduce EVs of entrepreneurs who more frequently participate in the farmers’ markets located closest to the company’s headquarters is probably

linked to what in the literature on EV is called “range anxi- ety”, according to which the more the distance to be travelled the more the reticence to purchase an EV, as a consequence of fears (not technically founded) linked to the battery charge life and the few charging points available along the route (Ramos- Real et al., 2018; Bunce et al., 2014). Moreover, this correla- tion could also indicate that those farmers more oriented and culturally convinced to take part in SFSC are also the more aware of the need to adopt further sustainability measures to improve their overall business, both from an ethical and con- sumer’s acceptance point of view, confirming the priority of SFSC farmers to act as “profit sufficers” rather than “profit maximisers” as suggested by Ilbery and Kneafsey (1998) and Jarosz (2008). Finally, this result opens up new interesting debates in the literature on SFSCs and the Food Miles concept, in that seeing local farmers operating in closest local markets as important actors can really support a shift from arguments focusing solely on production methods to ones which also include transport and distribution lines. Limitations recently suggested by Kemp et al. (2010) and Schmitt et al. (2017) indicate that measurements of CO2 emissions and the environ- mental impacts of SFSCs should be reformulated and deep- ened, so as to prompt reflection about improving efficiency.

Giving the high current market entry costs for EVs, sup- port measures are seen as a necessity. In this regard, our results show a great preference for measures mainly oriented at covering direct costs related to the purchasing of EVs.

Indeed, despite the development of charging infrastructure being on the top of the list of priorities for amass EV deploy- ment, as demonstrated by the last Regulations and Action Plans approved in Italy and, in turn, in Sicily, the most impor- tant support measure necessary is the one linked to purchase subsidies, as also emphasized by Santos and Davis (2019).

In this regard, Morganti and Browne (2018) add that the implementation of public incentives could favour the uptake of EVs by entrepreneurs, with positive effects on air quality in urban environments and greater acceptance by operators.

Conclusions

This is a preliminary analysis, the aim of which was to investigate the behaviour of local producers operating in the SFSC of the Province of Palermo, in relation to the opportu- nity to introduce an EV for the purpose of freight transporta- tion to local farmers’ markets. The case study explored this topic by employing the universal sample of SFSC farmers regularly registered in one of the four recognised farmer’s associations managing local markets in that area. The final sample was made up of 42 farmers out of 59. Results are interesting and original primarily because they contribute to enrich the literature on the pro-environmental behaviour linked to the debate currently open worldwide on how ensur- ing an effective de-carbonisation of the transport system.

This is a matter that, although it already involves all dimen- sions of civil and economic daily life, calls for more strin- gent and urgent measures especially in relation to the food industry.

In light of this, the study has interesting theoretical, managerial and political implications. In particular, the case

study reveals that farmers who mostly participate in the farmers’ markets and travel the shortest distances are more willing to introduce EVs for the distribution of their prod- ucts. The same behaviour is found in farms whose managers and owners show high interest towards the shift from carbon transport systems to electrical ones, and which are more sen- sitive to ecological and environmental sustainability issues.

The results emphasize how ethical factors, represented here by high environmental concerns, as well as awareness about the most known limits of EV in ensuring autonomy over longer distances, are the main factors that should be taken into account by policy-makers when approaching concrete political measures addressed to promote such a shift. These highlighted factors should be considered also as important selecting indicators when Action Plans in the SFSC sector will be planned, thus avoiding support measures which do not take into account cultural, ethical and distance informa- tion of eligible firms. However, although the infrastructure is a condition sine qua non for the diffusion of EV, it is impor- tant to pay particular attention to the study results that sug- gest that the majority of entrepreneurs participating in the SFSC indicated their most favourite EV support measure to be a non-repayable grant for the EV purchase.

From a theoretical perspective, the employment of an extended model of the TPB to which the environmental opinions of entrepreneurs have been incorporated further contributes to the development of the theory itself. Results show that TPB is a useful theory to investigate behaviours of the entrepreneurs operating in the SFSC as well as to know which characteristics linked to the distribution of goods are identified as main drivers for the effective introduction of EV to be intended here as the greener transport mean currently available in the market.

Specific implications also arise for SFSC farmers, sug- gesting that the shift towards an electric transport system should be seriously considered as a further competitive advantage able to meet consumer’s expectations towards more and more local farmers sustainability effort. Moreover, such a business choice should be mainly taken into account in those cases where distances travelled are over a reduced range, so suitable for the actual battery average duration.

Although this study extended our understanding of farmers’ intention to introduce EVs inside their business, it has likewise a number of certain limitations that need to be considered in future studies. The first limit is linked to the case study method selected, which does not allow for the generalisation of results. Although the sample employed is statistically significant even if it represents a small scale sample, representing the overall Sicilian region, it possesses inherently a limitation. For this reason, future research might next extend the sample at least to the regional level, pay- ing particular attention, when crossing the regional borders, to accurately considering the cultural and ethical dimen- sions of each of the areas investigated, together with fac- tors linked to the infrastructure development status (such as, the number of charging stations, support measures in force, discounts to enter in urban zones, etc). Secondly, the study has been performed only inside a farmers’ market, exclud- ing the other alternative short supply chains such as shop- pers, local e-commerce and other similar business models.

As a consequence, future work should engage more entre- preneurs working in other business distribution channels of the SFSC. Finally, targeted SWOT analysis and also cost- benefit analysis could be deepened in future research so as to acquire economic data useful to supporting an effective private-public partnership ensuring a more rapid EV diffu- sion, while also considering the possibility of case-by-case interaction between farmers and research centres to better conceive of a product, in this case battery and vehicle, that is more oriented to SFSC farmer needs.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted as part of the EnerNET- Mob project, Cod. 4MED 17_2.3.M123_040, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, INTERREG Mediterranean programme. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

Adnan, N., Nordin, S.M., Bahruddin, M.A. and Tareq, A.H. (2019):

A state-of-the-art review on facilitating sustainable agriculture through green fertilizer technology adoption: Assessing farmers behaviour. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 86, 439–452.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.02.040

Ajzen, I. (1991): The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50 (2), 179–211.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2002): Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, lo- cus of control, and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32 (4), 665–683. https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980): Understanding Attitude and Predicting Social Behavior. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall Publisher.

Ajzen, I. and Madden, T.J. (1986): Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22 (5), 453–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(86)90045-4 Arunrat, N., Wang, C., Pumijumnong, N., Sereenonchai, S. and Cai,

W. (2017): Farmers’ intention and decision to adapt to climate change: a case study in the Yom and Nan basins, Phichit prov- ince of Thailand. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 672–685.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.058

Berenguer, J., Corraliza, J.A. and Martín, R. (2005): Rural- Urban Differences in Environmental Concern, Attitudes, and Actions. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 21 (2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.21.2.128

Bunce, L., Harris, M. and Burgess, M. (2014): Charge up then charge out? Drivers perceptions and experiences of electric vehicles in the UK. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 59, 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2013.12.001 Coley, D., Howard, M. and Winter, M. (2011): Food miles: time for

a re-think? British Food Journal, 113 (7), 919–934. https://doi.

org/10.1108/00070701111148432

Cowell, S. and Parkinson, S. (2003): Localization of UK Food Production: An analysis using land area and energy as indica- tors. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 94 (2), 221–236.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(02)00024-5

Dang, H.L., Li, E., Nuberg, I. and Bruwer, J. (2014): Under- standing farmers’ adaptation intention to climate change: a structural equation modelling study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Environmental Science & Policy, 41, 11–22. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.04.002

Dunlap, R.E. and Van Liere, K.D. (1978): The new environmen- tal paradigm. The Journal of Environmental Education, 9 (4), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.1.19-28

Dunlap, R.E., Van Liere, K.D., Mertig, A.G. and Jones, R.E. (2000):

Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm:

A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56 (3), 425–442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Dupuis, E.M. and Goodman, D. (2005): Should We Go ‘Home’

to Eat? Toward a Reflexive Politics of Localism. Journal of Rural Studies, 21 (3), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrur- stud.2005.05.011

Edwards-Jones, G. (2010): Does Eating Local Food Reduce the Environmental Impact of Food Production and Enhance Con- sumer Health? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69 (4), 582–591. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665110002004 Egbue, O., Long, S. and Samaranayake, V.A. (2017): Mass deploy-

ment of sustainable transportation: evaluation of factors that influence electric vehicle adoption. Clean Technologies and En- vironmental Policy, 19 (7), 1927–1939. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s10098-017-1375-4

Feagan, R.B. and Morris, D. (2009): Consumer Quest for Em- beddedness: A Case Study of the Brantford Farmers Market.

International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33 (3), 235–243.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00745.x

Fielding, K.S., Terry, D.J., Masser, B.M., Bordia, P. and Hogg, M.A. (2005): Explaining landholders’ decisions about ripari- an zone management: The role of behavioural, normative, and control beliefs. Journal of Environmental Management, 77 (1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.03.002

Fielding, K.S., Terry, D.J., Masser, B.M. and Hogg, M.A. (2008):

Integrating social identity theory and the theory of planned be- havior to explain decisions to engage in sustainable agricultural practices. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47 (1), 23–48.

https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X206792

Galati, A., Siggia, D., Crescimanno, M., Martín-Alcalde, E., Saurí Marchán, S. and Morales-Fusco, P. (2016): Competitiveness of short sea shipping: The case of olive oil industry. British Food Journal, 118 (8), 1914–1929. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05- 2016-0193

Garrone, L. (2017): Consumi consapevoli, la sfida dei Mercati Contadini. Corriere della Sera. Available at: https://www.corrie- re.it/extra-per-voi/2017/02/17/consumi-consapevoli-sfida-mer- cati-contadini-8717e540-f50d-11e6-acae-b28574795707.shtm- l?refresh_ce-cp (Accessed June 2019)

Giampietri, E., Verneau, F., Del Giudice, T., Carfora, V. and Fin- co, A. (2018): A Theory of Planned behaviour perspective for investigating the role of trust in consumer purchasing de- cision related to short food supply chains. Food Quality and Preference, 64, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.

2017.09.012

Hall, C. and Moran, D. (2006): Investigating GM risk percep- tions: A survey of anti-GM and environmental campaign group members. Journal of Rural Studies, 22 (1), 29–37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.05.010

Hawcroft, L.J. and Milfont, T.L. (2010): The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years:

A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30 (2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.003

Henneberry, S.R., Whitacre, B. and Agustini, H.N. (2009): An Evaluation of the Economic Impacts of Oklahoma Farmers Markets. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 40 (3), 1–15.

Ilbery, B. and Kneafsey, K. (1998): Product and Place: Promoting Quality Products and Services in the Lagging Rural Regions of the European Union. European Urban and Regional Studies, 5 (4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649800500404 Jarosz, L. (2008): The City in the Country: Growing Alternative

Food Networks in Metropolitan Areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 24 (3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.10.002 Kaiser, F.G., Hartig, T., Brügger, A. and Duvier, C. (2011): En- vironmental protection and nature as distinct attitudinal objects: An application of the Campbell paradigm. Envi- ronment and Behavior, 45 (3), 369–398. https://doi.org/

10.1177/0013916511422444

Kemp, K., Insch, A., Holdsworth, D.K. and Knight, J.G. (2010):

Food miles: Do UK consumers actually care? Food Policy, 35 (6), 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.05.011 Kissinger, M. (2012): International trade related food miles – The

case of Canada. Food Policy, 37 (2), 171–178. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.01.002

Marsden, T., Banks, J. and Bristow, G. (2002): Food Supply Chain Approaches: Exploring their Role in Rural Development.

Sociologia Ruralis, 40 (4), 424–438. https://doi.

org/10.1111/1467-9523.00158

Menozzi, D., Fioravanzi, M. and Donati, M. (2015): Farmer’s moti- vation to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. Bio-based and Applied Economics, 4 (2), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.13128/

BAE-14776

Migliore, G., Schifani, G. and Cembalo, L. (2015): Opening the black box of food quality in the short supply chain: Effects of conventions of quality on consumer choice. Food Quality and Preference, 39, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.food- qual.2014.07.006

Morganti, E. and Browne, M. (2018): Technical and operational obstacles to the adoption of electric vans in France and the UK:

An operator perspective. Transport Policy, 63, 90–97. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.12.010

Paxton, A. (1994): The food miles report: the dangers of long dis- tance food transport. SAFE Alliance.

Pearson, D., Henryks, J., Trott, A., Jones, P., Parker, G., Dumaresq, D. and Dyball, R. (2011): Local Food: Under- standing Consumer Motivations in Innovative Retail For- mats. British Food Journal, 113 (7), 886–899. https://doi.

org/10.1108/00070701111148414

Pianeta Mercati (2019): Secondo gruppo in Sicilia. Available at:

http://www.pianetamercati.com/ht/siamo-in-secondo-grup- po-in-sicilia/ (Accessed June 2019)

Pienaar, E.F., Lew, D.K. and Wallmo, K. (2015): The importance of survey content: Testing for the context dependency of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale. Social Science Research, 51, 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.09.005 Plötz, P., Schneider, U., Globisch, J. and Dütschke, E. (2014): Who

will buy electric vehicles? Identifying early adopters in Ger- many. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 67, 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.06.006

Quak, H., Nesterova, N., van Rooijen, T. and Dong, Y. (2016): Zero Emission City Logistics: Current Practices in Freight Elec- tromobility and Feasibility in the Near Future. Transportation Research Procedia, 14, 1506–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

trpro.2016.05.115

Ramos-Real, F.J., Ramírez-Díaz, A., Marrero, G.A. and Perez, Y. (2018): Willingness to pay for electric vehicles in island

regions: The case of Tenerife (Canary Islands). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 98, 140–149. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.09.014

Renting, H., Marsden, T.K. and Banks, J. (2003): Understand- ing Alternative Food Networks: Exploring the Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Rural Development. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 35 (3), 393–411. https://doi.

org/10.1068/a3510

Rezaei, R., Mianaji, S. and Ganjloo, A. (2018): Factors affecting farmers’ intention to engage in on-farm food safety practices in Iran: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Rural Studies, 60, 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrur- stud.2018.04.005

Rezvani, Z., Jansson, J. and Bodin, J. (2015): Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agen- da. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environ- ment, 34, 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2014.10.010 Roininen, K., Arvola, A. and Lahteenmaki, L. (2006): Exploring

consumers’ perceptions of local food with two different qualita- tive techniques: laddering and word association. Food Quality and Preference, 17 (1-2), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.food- qual.2005.04.012

Santos, G. and Davies, H. (2019, in press): Incentives for quick penetration of electric vehicles in five European countries:

Perceptions from experts and stakeholders. Transportation Re- search Part A: Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

tra.2018.10.034

Schmitt, E., Galli, F., Menozzi, D., Maye, D., Touzard, J.M., Marescotti, A., Six, J. and Brunori, G. (2017): Comparing the sustainability of local and global food products in Europe.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 165, 346–359. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.039

Shin, Y.H. and Hancer, M. (2016): The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the in- tention to purchase local food products. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 19 (4), 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/15 378020.2016.1181506

Smith, P. and Smith, T.J.F. (2000): Transport costs do not negate the benefits of agricultural carbon mitigation options. Ecolo- gy Letters, 3 (5), 379–381. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461- 0248.2000.00176.x

Spesa del Contadino (2019): Cerca le fattorie che fanno vendita diretta. Available at: https://www.spesadalcontadino.com/

(Accessed June 2019).

Van Dijk, W.F.A., Lokhorst, A.M., Berendse, F. and de Snoo, G.R.

(2016): Factors underlying farmers’ intentions to perform un- subsidised agri-environmental measures. Land Use Policy, 59, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.09.003 Van Hauwermeiren, A., Coene, H., Engelen, G. and Mathijs, E.

(2007): Energy Lifecycle Inputs in Food Systems: A Com- parison of Local Versus Mainstream Cases. Journal of En- vironmental Policy & Planning, 9 (1), 31–51. https://doi.

org/10.1080/15239080701254958

Yin, R. K. (1984): Applied social research methods series Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE Publications.

Zeweld, W., Huylenbroeck, G., Tesfay, G. and Speelman, S. (2017):

Smallholder farmers’ behavioral intentions towards sustainable agricultural practices. Journal of Environmental Management, 187, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.11.014