Availableonlineatwww.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

j ou rn a l h o m epa ge :w w w . i n t l . e l s e v i e r h e a l t h . c o m / j o u r n a l s / d e m a

Degree of conversion and in vitro temperature rise of pulp chamber during polymerization of flowable and sculptable conventional, bulk-fill and

short-fibre reinforced resin composites

Edina Lempel

a,∗, Zsuzsanna ˝ Ori

b,c, Dóra Kincses

a, Bálint Viktor Lovász

d, Sándor Kunsági-Máté

c,e, József Szalma

faDepartmentofRestorativeDentistryandPeriodontology,UniversityofPécs,5DischkaGy ˝oz ˝oStreet,PécsH-7621, Hungary

bDepartmentofGeneralandPhysicalChemistry,UniversityofPécs,6IfjúságStreet,PécsH-7624,Hungary

cJánosSzentágothaiResearchCenter,20IfjúságStreet,PécsH-7624,Hungary

dUniversityofPécsMedicalSchool,12SzigetiStreet,PécsH-7624,Hungary

eFacultyofPharmacy,InstituteofOrganicandMedicinalChemistry,UniversityofPécs,12SzigetiStreet,Pécs H-7624,Hungary

fDepartmentofOralandMaxillofacialSurgery,UniversityofPécs,5DischkaGy ˝oz ˝oStreet,PécsH-7621,Hungary

a r t i c l e i n f o

Keywords:

Pulpaltemperature Degreeofconversion Resincomposite Bulk-fill Fiber-reinforced

a bs t r a c t

Objective.Determinethedegreeofconversion(DC)andinvitropulpaltemperature(PT)rise oflow-viscosity(LV)andhigh-viscosity(HV)conventionalresin-basedcomposites(RBC), bulk-fillandshort-fibrereinforcedcomposites(SFRC).

Methods.Theocclusalsurfaceofamandibularmolarwasremovedtoobtaindentinethick- nessof2mmabovetheroofofthepulpchamber.LVandHVconventional(2mm),bulk-fill RBCs(2–4mm)andSFRCs(2–4mm)wereappliedinamold(6mminnerdiameter)placedon theocclusalsurface.PTchangesduringthephoto-polymerizationwererecordedwithather- mocouplepositionedinthepulpchamber.TheDCatthetopandbottomofthesampleswas measuredwithmicro-Ramanspectroscopy.ANOVAandTukey’spost-hoctest,multivariate analysisandpartialeta-squaredstatisticswereusedtoanalyzethedata(p<0.05).

Results.ThePTchangesrangedbetween5.5–11.2◦C.AllLVand4mmRBCsexhibitedhigher temperaturechanges.HigherDCweremeasuredatthetop(63–76%)ofthesamplesascom- paredtothebottom(52–72.6%)inthe2mmHVconventionalandbulk-fillRBCsandineach 4mmLVandHVmaterials.TheSFRCsshowedhighertemperaturechangesandDC%as comparedtotheotherinvestigatedRBCs.ThetemperatureandDCwereinfluencedbythe compositionofthematerialfollowedbythethickness.

Significance.ExothermictemperatureriseandDCaremainlymaterialdependent.HigherDC valuesareassociatedwithasignificantincreaseinPT.LVRBCs,4mmbulk-fillsandSFRCs exhibitedhigherPTs.Bulk-fillsandSFRCsappliedin4mmshowedlowerDCsatthebottom.

©2021TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierInc.onbehalfofTheAcademyofDental Materials.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗ Correspondingauthorat:DepartmentofRestorativeDentistryandPeriodontology,UniversityofPécs,5.DischkaGyStreet,PécsH-7621, Hungary.

E-mailaddress:lempel.edina@pte.hu(E.Lempel).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2021.02.013

0109-5641/©2021TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierInc.onbehalfofTheAcademyofDentalMaterials.Thisisanopenaccessarticle undertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Settingreactionofphoto-polymerizableresin-basedcompos- iterestorativematerials(RBC)isinducedbylightcuringunits (LCU)atdifferentirradiancelevelsand exposuredurations.

Acertainlevelofradiantexposureensuresagivendegreeof monomertopolymerconversion(DC)inthe RBC[1,2].The amount oflight energytransmittedto the RBC restoration isinfluencedbyseveral factors,suchasexposureduration, powerdensityoftheLCU,theaccordancebetweenthespectral absorption range ofthe photoinitiatorsand spectralemis- sion profileof the curing unit, distancebetween the light guidetipandtherestoration,composition,shade,opacityand thicknessoftheRBCmaterial[1,3–6].Evenifthesamenum- berofradicalsaregenerated, manyofthemdonotlast as longundertheconditionofhigherincidentlightirradiance andshorterirradiationtimeasthosegeneratedunderlower incident lightirradianceand longer irradiation time.Thus, evenat an identical radiantexposure, the rate of spectral radiantpowerdeliverymayalsoinfluencethedegreeofcon- versionoflightactivatedRBCs[7].Severalstudiesconfirmed thatahigherdegreeofpolymerizationleadstobetterphys- icalandchemicalpropertiessuchascompressive strength, microhardness,wearresistanceandbiocompatibility[8–11].

Consequently,enhancingtheDCisessentialforthedurabil- ityofRBCrestorations[12].AnimprovedDCcanbeachieved byusingahigh-irradiancecuringunitand/orbylengthening theexposureduration[13],however,thisprocessesinvolves thermal reactions, which represent a potential hazard for thedentalpulptissue[14,15].Despiteattemptstodefinethe thresholdtemperaturevaluewhichwouldindicateapoten- tially irreversiblepulpaldamage,the multiplicityoffactors involvedintheheattransfer(thicknessofthedentaltissues, effectofbloodcirculationinthepulpchamber,fluidmotionin thedentinaltubulesandthesurroundingperiodontaltissues) makesitdifficulttotranslateinvitrofindingstoclinicallyrel- evantinferences[14,16,17].Eventhoughtherealvalueofthe potentiallyharmfulcriticaltemperatureriseisstillcontrover- sial,itiswidelyacceptedthatthetemperatureriseinthepulp shouldbekeptaslowaspossibleduringdentalprocedures involvingthepolymerizationoflightcuredmaterials[18–21].

Temperature rise during polymerization of RBCs is attributedtoboththeexothermicreactionofpolymerization and the energyabsorbed during the irradiationfrom LCUs [22,23].Severalstudiesinvestigatedthistopic,addressingthe effectofRBCtype,shade,thickness,curingunitradiantenergy andspectralcharacteristics ontemperature risewithinthe pulpchamber[15,24–27].Mostoftheinvestigationsfound,that comparedtothelowintensitycuringunits,thehigh inten- sitytypesproducedasignificantlyhighertemperaturerisein thepulpchamber[17,28].Asidefromthethermaleffectofthe lightcuringunit,theexothermicreactionistheothermain contributingfactortotheincreaseintemperatureduringthe earlystagesofpolymerization[29].Thecompositionofthe RBCcanalsoinfluencethermalchanges.TheamountofC C bondsisproportionaltotheexothermicheatgeneratedduring cureandtheinorganiccompartmentsaffecttheheatdiffu- sionwithinthematerialbytheircapacitytoabsorbexternal energy[30,31].Thus,thematrixtofillerratio,thecharacteristic

featuresofthedimethacrylatemonomers,fillerparticlesand pigmentsalsoplayimportantrolesinthetemperatureriseof RBCs[23,29].

NumeroustypesofdentalRBC areavailableonthemar- ketwithdifferentmatrix-fillercomponents,consistenciesand recommendedapplicationmethods.Besidestheconventional high-viscositypastesandlow-viscosityflowableRBCs,applied incrementallymaximumintwo-millimeter-thicklayers,the so-calledbulk-fillRBCsareincreasinglypopularamongclin- icians,sincetheseareapplicableinathicknessof4–5mm withoutlayering.Althoughitwasreported,thatthesebulk-fill materialsshowlowerpolymerizationshrinkage,theadequacy ofthedepthofcureisstillcontentious[32–34].Theincreased thicknessoftheRBClayernegativelyinfluenceslighttrans- missionandDC[35].Thethermalloadonthepulptissueis alsocontroversial.Anumberofresearchersfoundthatbulk-fill RBCsgeneratedagreaterincreaseinpulpaltemperaturethan conventionalones[36,37].Onthecontrary,someoftheinvesti- gationsconcludedthatbulk-fillRBCs,especiallyhigh-viscosity pastescanreducethermalloadonthepulpchamber[28,38].

Although,particulateRBCsaredurablerestorativematerials, oneofthemostfrequentfailuresisthefractureoftherestora- tion[39].Toovercomethismechanicallimitationandenhance theirphysicalproperties,fiberreinforcementofconventional dental compositeswas introduced. Thereinforcement was duetothestresstransferfrom thematrix totheshortran- domlyorientedfiberswhichoccursuponloadingleadingto highfractureresistance[40,41].Whilesculptableandflowable short-fibrereinforcedresincomposites(SFRC)areincreasingly usedmaterialsinclinicalpractice,especiallyindeepcavities, accordingtoourbestknowledge,nodataareavailableinthe literatureaddressingthethermaleffectofthesematerialson thepulp.

Thepurposeofthepresentstudywastocompareinvitro thethermalchangeinthepulpchamberduringthepolymer- izationofhigh-andlow-viscosityconventionalRBCsapplied in2mmthickness,light-curedfor20or40sandhigh-and low-viscositybulk-fillandshort-fibrereinforcedRBCsplaced in2and4mmlayerthicknessexposedtolightfor20sthrough aremainingdentinethicknessof2mm.Furtheraimswereto determinethedeliveredradiantexposureandrelatedDCof theinvestigatedmaterialsandtoassesstheinfluenceoflayer thicknessandexposuretimeonpulpaltemperatureriseand DC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Resincompositesandradiantexposure

DuringthisinvitrostudysixbrandsofRBCs–aconventional high-viscosity (HV) sculptable microhybrid, a low-viscosity (LW)flowablenanofill,HVandLVbulk-fillandHVandLVshort- fibrereinforcedRBC –wereanalyzed.Thebrands,chemical compositionsandmanufacturersarepresentedinTable1.

Materialsweretestedinthelayerthicknessrecommended bythemanufacturer,thusconventionalhigh-viscosity(Conv- HV-2 mm) and low-viscosity (Conv-LV-2 mm) RBCs in 2 mmlayerthickness,high-viscosity(Bulk-HV-4mm)andlow- viscosity(Bulk-LV-4mm)bulk-fillandSFRC(SFRC-HV-4mm

Table1–Materials,manufacturersandcomposition.

Group Material Manufacturer Shade Organicmatrix Filler Fillerloading

(vol%/wt%) Highviscosity

conventional RBC

FiltekZ250 3MESPE,St.Paul, MN,USA

A2 BisGMA,UDMA,

BisEMA, TEGDMA

0.01–3.5m (mean0.6) Zr-silica

60/82

Lowviscosity conventional RBC

FiltekSupreme Flowable Restorative

3MESPE,St.Paul, MN,USA

A2 BisGMA,

TEGDMA, Procrylatresin

20–75nmsilica, 0.6–10mcluster Zr-silica,0.1–5

mYbF3

46/65

Highviscosity bulk-fillRBC

FiltekOneBulk FillRestorative

3MESPE,St.Paul, MN,USA

A2 AFM,UDMA,

AUDMA,DDDMA

20nmsilica,4–11 nmzirconia, clusterZr-silica, 0.1mYbF3

58.5/76.5

Lowviscosity bulk-fillRBC

SurefilSDRFlow+ Dentsply, Milford,DE,USA

U Modified

UDMA,TEGDMA, di-and trimethacrylate resins

4.2mBa-Al-F-B silicateglass, Sr-Al-Fsilica,YbF

47.4/70.5

Highviscosity short-fibre reinforcedRBC

EverXPosterior GCEurope, Leuven,Belgium

U BisGMA,

TEGDMA,PMMA

0.7mbarium glass(65.2%),17

mx1-2mm shortE-glass fibers(9%)

53.6/74.2

Lowviscosity short-fibre reinforcedRBC

EverXFlow GCEurope, Leuven,Belgium

U BisEMA,UDMA 0.7mbarium

glass(45%),6× 140mshort E-glassfibers (25%)

48/70

Abbreviations:RBC:resinbasedcomposite;U:universal;UDMA:urethanedimethacrylate;AUDMA:aromaticurethanedimethacrylate;AFM:

additionfragmentationmonomer;DDDMA:1,12-dodecanedimethacrylate;TEGDMA:triethyleneglycoldimethacrylate;BisEMA:bisphenol- Apolyethyleneglycoldietherdimethacrylate;BisGMA:bisphenol-Adiglycidiletherdimethacrylate;PMMA:polymethylmethacrylate;vol.%:

volume%;wt.%:weight%.

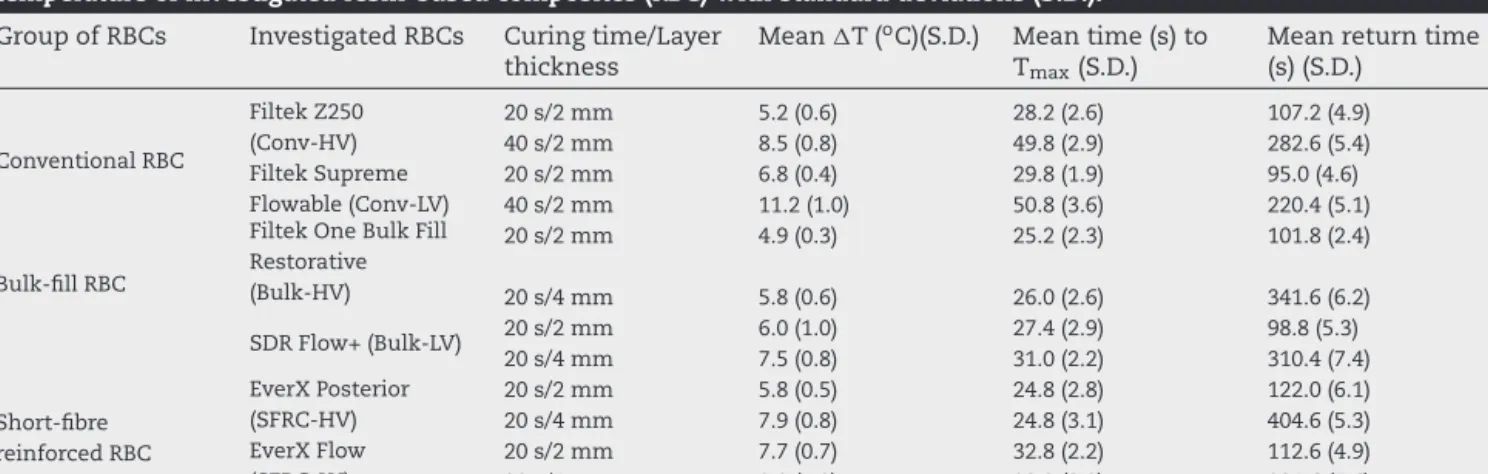

Table2–Meantemperaturechange(T),timetoreachthemaximumtemperature(Tmax),returningtimetotheinitial temperatureofinvestigatedresin-basedcomposites(RBC)withstandarddeviations(S.D.).

GroupofRBCs InvestigatedRBCs Curingtime/Layer thickness

MeanT(oC)(S.D.) Meantime(s)to Tmax(S.D.)

Meanreturntime (s)(S.D.)

ConventionalRBC

FiltekZ250 (Conv-HV)

20s/2mm 5.2(0.6) 28.2(2.6) 107.2(4.9)

40s/2mm 8.5(0.8) 49.8(2.9) 282.6(5.4)

FiltekSupreme Flowable(Conv-LV)

20s/2mm 6.8(0.4) 29.8(1.9) 95.0(4.6)

40s/2mm 11.2(1.0) 50.8(3.6) 220.4(5.1)

Bulk-fillRBC

FiltekOneBulkFill Restorative (Bulk-HV)

20s/2mm 4.9(0.3) 25.2(2.3) 101.8(2.4)

20s/4mm 5.8(0.6) 26.0(2.6) 341.6(6.2)

SDRFlow+(Bulk-LV) 20s/2mm 6.0(1.0) 27.4(2.9) 98.8(5.3)

20s/4mm 7.5(0.8) 31.0(2.2) 310.4(7.4)

Short-fibre reinforcedRBC

EverXPosterior (SFRC-HV)

20s/2mm 5.8(0.5) 24.8(2.8) 122.0(6.1)

20s/4mm 7.9(0.8) 24.8(3.1) 404.6(5.3)

EverXFlow (SFRC-LV)

20s/2mm 7.7(0.7) 32.8(2.2) 112.6(4.9)

20s/4mm 9.0(1.2) 29.2(2.3) 384.6(7.6)

andSFRC-LV-4mm)RBCsin4mmlayerthickness.Inaddition, thelast4RBCsweremeasuredin2mmthicknessaswell(Bulk- HV-2mm;Bulk-LV-2mm;SFRC-HV-2mm;SFRC-LV-2mm).All materialswereirradiatedwiththesameLightEmittingDiode (LED)curingunit(LED.D,Woodpecker,Guilin,China;average lightoutput givenbythe manufacturer850–1000mW/cm2;

=420–480nm;8mmexit diameterfiberglasslightguide) instandardmode for20 saccordingtothe manufacturer’s instruction,poweredbyalinecordatroomtemperatureof23

◦C±1◦C,controlledbyanair-conditioner.Additionally,tosee theinfluenceofexposureduration,samplesofconventional

RBCswerealsopolymerizedwithanextendedexposuretime of40s(Conv-HV-2mm-40s;Conv-LV-2mm-40s).Theradi- antexitance(mW/cm2)andexposure(J/cm2)deliveredbythe LCUoperatinginthestandardmodeweremeasuredusinga checkMARCradiometer(BluelightAnalytics,Halifax,Canada).

Measurementswererecordedintheabovementionedtwelve groups,fivetimesforeachduringthepreparationofthespec- imens(n=60).RegardingthetypeofRBC,layerthicknessand exposuredurationthe investigatedgroupsare presentedin Table2.TheradiantexitanceatthetipoftheLCUwasdeter- minedbyplacingthetipdirectlyatadistanceof0mmfrom

theradiometersensorandtheradiantexposurewascalcu- latedbothatanexposuredurationof20sand40s.Thiswas repeatedwiththeinterpositionofablackpaperwitha6mm diameterholeonit,torepresenttheirradiancedeliveredto thetopofthematerials.Thelightattenuationoftheempty cylindricalpolytetrafluoroethylene(PTFE)moldwithaninner diameterof6mm,externaldiameterof12mmandheightof 2or4mmwasalsomeasuredbyplacingthetipoftheLCU directlyoverthemold.Interpositionofablackpaperwitha 6mmdiameterholebetweenthemoldandthesensorpre- ventedlighttransmissionthroughthemoldtothecheckMARC sensor.Theradiantexposurevalueswerecalculatedfromthe recordedradiantexitancebothatacuringtimeof20sand40s.

Toestimatetheradiantexitanceandradiantexposuretrans- mittedthrougheachRBCduringpolymerization,themoldwas positionedcentrallyonthesensor.Polyester(Mylar)stripwas usedtoseparatethesensorfromtheRBCwhichwasfilledin themold.ToavoidcontactwithoxygenthetopoftheRBCwas protectedwithaMylarstripbeforethepolymerization.

2.2. Micro-Ramanspectroscopymeasurement

ThesameRBCsamplesmadetoestimatetheradiantexposure transmittedthrough each RBC during polymerization were usedtomeasuretheDC.Thesampleswerethenplacedinan incubator(Cultura,IvoclarVivadent,Schaan,Liechtenstein)at 37±1◦Cand90%±10%relativehumidityandstoredindark.

The24hpost-cureDCvaluesofthepolymerizedRBCsam- pleswereexaminedusingaLabramHR800ConfocalRaman spectrometer(HORIBAJobinYvonS.A.S.,LongjumeauCedex, France).Thefollowingsetsofparameterswereapplieddur- ingthemicro-Ramanmeasurements:20mWHe-Nelaserwith 632.817nmwavelength,spatialresolution∼15m,magnifi- cation×100(OlympusUKLtd.,London,UK).Usingaspectral resolutionof∼2.5cm−1, satisfactoryresults were obtained sincethe two peaks analyzedwere ∼30 cm−1 apart. Spec- trawere takenbothonthetop andbottomsurfacesofthe RBC specimensatthree randomlocations (central, periph- eralregionand areabetween)andwithanintegrationtime of10s.Tenacquisitionswereaveragedforeachgeometrical point.SpectraofunpolymerizedRBCweretakenasreference.

Post-processingofspectrawasperformedusingthededicated softwareLabSpec5.0(HORIBAJobinYvonS.A.S.,Longjumeau Cedex,France).Theratioofdouble-bondcontentofmonomer topolymerintheRBCwascalculatedaccordingtothefollow- ingequation:

DC%=

1−

Rcured

Runcured

×100

whereR is the ratio of peak intensitiesat 1639cm−1 and 1609cm−1associatedtothealiphaticandaromatic(unconju- gatedandconjugated)C CbondsincuredanduncuredRBCs, respectively.

2.3. Samplepreparationforpulpaltemperature measurement

Afreshlyextracted,caries-free,cleanedhumanthirdmolarto beusedinthisstudywaskeptwetindistilledwater.Asingle toothmodelwaschosenforallexperimentaltrialstolimitany

Fig.1–(OPTIONAL)Schematicfigureoftheexperimental set-upforpulpaltemperaturemeasurements.

effectsofstructuralandcompositionaldifferencesinenamel and dentin.Theocclusalsurfacewas groundflat leavinga dentinthicknessoftwomillimetersfromtheroofofthepulp chamber.Theapicesoftherootsweresectioned5mmfrom the furcationtoexposethe rootcanals.Allpulpal residues were removed withendodontic files. This wasfollowed by 5.25%sodium-hypochloritethensalineirrigationanddrying withpaperpoints.Aholewascreatedonthemesialsideofthe toothwithaone-millimeterdiametercylindricaldiamondbur toallowtheinsertionofthe0.5mmdiameterCu/CuNither- mocoupleprobes(K-type,TCDirect,Budapest,Hungary).The thermocouplesensorwasfixedtothedentinonthetopofthe pulpchamberbymeansofathinlayerofcyanoacrylateglue (LoctiteSuperGlue,Loctite,Düsseldorf,Germany).Thelateral holewasclosedwithflowableRBC(FiltekSupremeFlowable, 3M,St.Paul,MN,USA).Theremainingdentinthicknessand positionofthethermocouplewereassessedradiographically.

Thentoreplicatethepulptissue,thepulpchamberandroot canalswereinjectedwithECGgel(AquaSoundBasic,Ultra- gelHungary2000,Budapest,Hungary).FlowableRBCwasused tocloseapicalorificesandthetoothwasembeddedinclear acryliconemillimeterbelowthe cemento-enameljunction.

Thetoothwasimmersedinawaterbathof36.5±0.5◦C.

Temperaturemeasurementsand heat registrationswere recorded by a registration device (El-EnviroPad-TC, Lascar ElectronicsLtd.,Salisbury,UK)attachedtotheK-typethermo- couplewithafrequencyofonemeasurementpersecondand resolutionof0.1◦C.ThePTFEmoldwasstackedontopofthe flatandpolishedocclusalsurfaceofthetooth.Firstofall,the thermaleffectofthelightcuringunit-bothaftera20and40 sexposure-wasmeasuredthroughtheempty2-and4-mm deepmold(Fig.1).Thetemperaturechangesofeachinvesti- gatedRBCswerealsomeasured:conventionalRBCsappliedin 2mmthicknesswithanexposuretimeof20and40s,bulk-fill andSFRCRBCsappliedin2-and4-mmthicknessesexposed for20s.Asnodental adhesivesystemwasused,thepoly- merizedRBCcouldeasilyberemovedfromthemoldwithout leavinganydepositsonthedentinsurface.Thisenabledthe useofthesametoothforeachmeasurement.Lightcuringwas initiatedwhenthetemperaturestabilizedaftertheRBCappli- cation.Temperatureswererecordedatthebeginning ofthe irradiationsandmeasurementscontinueduntiltheyreturned

totheinitialtemperature.Temperaturechangewasexpressed asthedifferencebetweentherecordedmaximaltemperature andtheinitialambienttemperature.Although,thetemper- atureofthe waterbathapparatus wassettoconstant,the repetitivemeasurementsfoundatemperaturevariationof0.5

◦C.Therefore, inordertoreduceerrorscaused byenviron- mentaltemperature changes,when calculating theresults, thetemperaturechangewasusedinsteadofthemaximum temperaturemeasurement.

Thetimetoreachthemaximumandtheinitialtempera- tureafterpolymerizationwerealsorecorded.Theprocedure wasrepeatedfivetimesforeachcombination(n=60).

2.4. Statisticalanalysis

The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v. 26.0 (SPSS,Chicago,IL,USA).Totestthenormalityofthedistri- butionofthedatatheKolmogorov–Smirnovtestwasapplied, followedbyaparametric statisticaltest.Thedifferences in temperaturechange,timetoreachthemaximum,returntime andinDCbetweenthetopandbottomoftheinvestigatedRBCs werecomparedwithone-wayanalysisofvariance(ANOVA).

Tukey’sposthocadjustmentwasusedformultiplecompari- soninallANOVAmodels.Multivariateanalysis(generallinear model)and partialeta-squared statistics were usedtotest theinfluenceanddescribetherelativeeffectsizeformaterial andthicknessasindependentfactors.Atwo-tailedindepen- dentt-testwasusedtocomparethedifferencebetweenthe temperaturechangethroughtheempty2vs.4mmdeepmold, irradiatedfor20vs.40s.Pvaluesbelow0.05wereconsidered statisticallysignificant.

3. Results

Basedonmeasurementstakenatthreedifferentlocationson theradiograph(buccal-radialprojection),thethicknessofthe remainingocclusaldentinwas2.1±0.2mm.Themaximum radiantexitanceoftheLEDLCUwas1170±15mW/cm2.The deliveredmaximumincidentradiantexposureswith20and 40sexposuredurationwere23.4±0.1and46.8±0.2J/cm2, respectively.Theradiantexitancewasreducedto930mW/cm2 bythe6mmorifice,thustheradiantexposureswith20and 40sexposuredurationswere18.6and37.2J/cm2,deliveredto thetopofthespecimens.The2−4mmdistancebetweenthe lightguide tipandtheradiometersensorand,additionally, the limitedorifice (6 mm indiameter) ofthe mold signifi- cantlydecreased theradiantexposure.Through the empty 2and 4mmmold,theradiantexposuredecreasedby42% (13.5J/cm2±0.1)and63%(8.7J/cm2±0.1),respectively.The LCUincreasedthepulptemperatureby2.7and5.1◦Cwhen theocclusalsurfacewasirradiatedthroughthe2mmdeep emptymoldfor20and40s,respectively.Thedifferencewas statisticallysignificant(t(8)=11.7,p<0.001).Comparedtothe 2mmdeepmold(2.7◦C),thetemperatureincreasewassig- nificantlylower(t(8)=4.4,p<0.01)throughthe4mmdeep emptymold(1.9◦C)lightcuredfor20s.Themeantemperature changesoftheinvestigatedRBCs,thetimesittooktoreachthe maximumaswellasreturntotheinitialtemperaturesafter polymerizationarepresentedinTable2.

Regardingtheexothermicreaction,eachRBCproducedsta- tisticallysignificantlyhighertemperatureincreaseinthepulp chamberthantheLEDunitalone.Subtractingthetempera- turerisecausedbytheLCUfromthethermalchangeinthe pulpchamberinducedbytheRBCgivesanestimationofthe heatgeneratedbytheexothermicreaction.Accordingtothis calculation–whichdoesnotaccountforthethermaltransfer betweenthethermodynamicsystemanditsenvironment–, theorderofexothermicthermalchangesthroughthe2mm dentinthickness wasthe following:SFRC-LV-4 mm(6.3 ◦C)

>SFRC-HV-4mm(5.2◦C)>Bulk-LV-4mm(4.8◦C)>Conv-LV-2 mm(4.1◦C)>Bulk-HV-4mm(3.1◦C)>Conv-HV-2mm(2.5◦C).

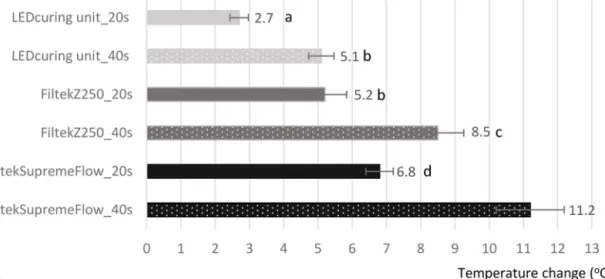

Thecomparisonofthermalchangeofhigh-andlow-viscosity conventional,bulk-fillandSFRCRBCswithrepresentativereg- istrationcurvesisshowninFig.2(A,B).

Ingeneral,thelow-viscosityRBCsshowedstatisticallysig- nificantly(p<0.001)highermeantemperaturechangeduring polymerization,irradiatedfor20s.Amongthedifferentgroups ofmaterials,theSFRCRBCsshowedasignificantlyhighertem- peraturechange(p<0.001).TheflowableRBCsneededlonger timetoreachthemaximumtemperature,butitwasstatisti- callysignificantonlyforthebulk-fillRBCs.However,thetime ittooktoreturntotheinitialambienttemperaturewassig- nificantly shorter (p< 0.001)for each low-viscosity RBC as comparedtothecondensableones.Thethermalchangesof sculptableandflowableconventionalRBCs irradiatedfor20 and40swithrepresentativetemperatureregistrationcurves arereportedinFig.3(A,B).

The extended exposure duration significantly increased themean temperaturechange(p<0.01)oftheinvestigated conventional RBCs.Subtractingthe thermalchange caused by the LCU(5.1 ◦C –40 s) alone, the exothermic tempera- tureriseinthepulpchamberwasestimatedtobe3.4◦Cfor theConv-HV-2mm-40sandalmostdouble,6.1◦CforConv- LV-2mm-40s.Although,theexposuredurationwasdoubled, thetimetoreachthemaximumtemperaturewasnot,how- everthetimeittooktoreturntobaselinewasmorethantwo timeslongercomparedtothesamplespolymerizedfor20s.

Regarding the influenceoflayerthickness, a1–2 ◦C higher temperatureincreasewasmeasuredinthecaseofthicker(4 mmvs.2mm)samples,whichweresignificantforalltypesof investigatedmaterials.Thethermalchangesofhighandlow viscositybulk-fillandSFRCRBCsin2-and4-mmlayerthick- nesses with representative temperature registration curves arepresentedinFig.4(A–C).

The temperature valueswere predominantly influenced bymaterial(p<0.001)followed bythickness(p<0.001)with partialeta-squaredvaluesof0.74and0.49,respectively.The interactionoffactorsmaterialxthicknessdidnotshowastatis- ticallysignificanteffectonthetemperaturechange(p=0.16) (partialeta-squared:0.15).Thetimetoreachthemaximum temperaturewasnotsignificant(p>0.05)asafunctionoflayer thicknesses,however,thetimetoreturntobaselinetempera- turewasthreetimeslongerforthethickersamples,whichwas statisticallysignificantforallgroupsofmaterials(p<0.001).

Thetemperatureincreaseduring20sofpolymerizationwas notconsistentwiththeradiantexposuresmeasuredthrough the2-and4-mmthicksamples.

Thelightattenuationwassignificant throughthe2mm (SFRC-LV-2mm54%<SFRC-HV-2mm56%<Bulk-LV-2mm73%

Fig.2–(A)Thermalchangeofhighandlowviscosityconventional,bulk-fillandshort-fibrereinforcedresin-based compositespolymerizedfor20s.Distinctalphabeticindicatesstatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweenthematerials.(B) Representativeregistrationcurvesofhighandlowviscosityconventional(2mm),bulk-fill(4mm)andshort-fibrereinforced (4mm)resin-basedcompositespolymerizedfor20s.

<Bulk-HV-2mm82%=Conv-LV-2mm82%<Conv-HV-2mm 88%) and 4mm (SFRC-LV-4mm 68% <SFRC-HV-4 mm71%

<Bulk-LV-4mm89%<Bulk-HV-4mm92%)thickRBCsamples.

Themeandeliveredradiantexposuresatthebottomof2−4 mmthickRBCmaterialsduringpolymerizationaregivenin Table3.

RegardingtheDCatthetopandbottomsurfacesinsam- plesappliedin2mmthickness,percentagesrangedbetween 66–75.4% and 60–72.6%, respectively. When samples were appliedinathicknessof4mmthevaluesrangedbetween 63–76%atthetopand52–69%atthebottom(Table3).Conv-

HV-2 mm, Bulk-HV-2 mmand all the 4mmthick samples (Bulk-HV-4 mm, Bulk-LV-4mm, SFRC-HV-4 mm, SFRC-LV-4 mm)showedstatisticallysignificantdifferencesbetweenthe topandbottomDCvalues(Fig.5and6).

The2mmthicklow-viscosityRBCs(Conv-LV-2mm,Bulk- LV-2 mm, SFRC-LV-2 mm) and SFRC-HV-2 mm provided similarlyhighDCvaluesonthetopasatthebottom.Thehigh- estDCatthetopwasachievedintheSFRCsamplesregardless ofthesamplethickness,followedbythelow-viscosityconven- tionalandbulk-fillRBCsappliedin2-and4-mmthicknesses.

The lowest degree of polymerization at the top was mea-

Fig.3–(A)Thermalchangeofhighandlowviscosityconventionalresin-basedcompositespolymerizedfor20svs.40s.

Distinctalphabeticindicatesstatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweenthematerials.(B)Representativeregistrationcurves ofhighandlowviscosityconventionalresin-basedcompositepolymerizedwith20svs.40s.

suredinthe high-viscosityconventional andbulk-fillRBCs.

TheresultsregardingtheDCatthebottomsurfaces,arecon- sistentwiththedecreasedradiantexposuredeliveredthrough the4mmthickspecimens.ThelowestDCwasachievedbythe Bulk-HV-4mm,followedbytheConv-HV-2mmandBulk-HV-2 mm.SignificantlyhigherDCvaluesweredetectedinBulk-LV- 4mmandSFRC-HV-4mmsamples.ThehighestDCsatthe bottomweremeasuredinallthe2mmthickflowablemate- rials(Conv-LV-2mm,Bulk-LV-2mm,SFRC-LV-2mm)and in SFRC-LV-4mmsamples.Theeffectsizeoffactor materialis significant(p<0.001)(partialeta-squaredis0.94)andhigher

ontheDCthantheeffectsizeoffactorthickness(partialeta squareis0.79),whichwasalsofoundtobeastrongandsta- tisticallysignificanteffect(p<0.001).Theinteractionbetween thetwovariables,materialxthickness,significantlyinfluenced theDCvalues(p=0.001)withaneffectsizeof0.35.

4. Discussion

Inthis invitrostudy theinfluenceofthepolymerizationof high-andlow-viscosityconventional,bulk-fillandSFRCRBCs

Fig.4–(A)Thermalchangeofhighandlowviscositybulk-fillandshort-fibrereinforcedresin-basedcompositesin2mmvs.

4mmlayerthickness.Distinctalphabeticindicatesstatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweenthematerials.(B)

Representativeregistrationcurvesofhighandlowviscositybulk-fillresin-basedcompositepolymerizedin2mmvs.4mm layerthickness.

(C)Representativeregistrationcurvesofhighandlowviscosityshort-fibrereinforcedresin-basedcompositepolymerizedin 2mmvs.4mmlayerthickness.

Table3–Topandbottomdegreeofconversionoftheinvestigatedmaterialsandradiantenergydeliveredtothebottom of2and4mmthickspecimens.

Resin- based composite (RBC)

Exposure duration

Layer thickness

Mean radiant energy (J/cm2)(S.D.)

Degreeofconversion(DC)(%)

Top Bottom DC 95%CI p-valuea

Lower Upper

FiltekZ250 20s 2mm 1.6(0.1) 66 60.4 5.6 −7.87 −3.72 <0.001

40s 2mm 3.2(0.2) 69 67 2 −3.36 −0.03 0.04

FiltekSupreme Flowable

20s 2mm 2.4(0.06) 72 70 2 −4.09 0.98 0.19

40s 2mm 4.7(0.1) 77 74 3 −6.18 0.18 0.06

FiltekOneBulkFill

Restorative 20s 2mm 2.4(0.1) 66 60 6 −8.72 −3.61 <0.001

4mm 0.7(0.05) 63 52 11 −13.57 −8.47 <0.001

SDRFlow+ 20s 2mm 3.6(0.07) 70 69 1 −3.16 0.96 0.25

4mm 1.0(0.08) 70 65 5 −5.11 −3.97 <0.001

EverXPosterior 20s 2mm 5.9(0.05) 75.4 72.6 2.8 −5.88 0.29 0.07

4mm 2.5(0.08) 73 68 5 −6.87 −3.16 <0.001

EverXFlow 20s 2mm 6.2(0.05) 75 72 3 −4.84 0.68 0.12

4mm 2.8(0.1) 76 69 7 −10.95 −3.01 <0.001

a One-wayanalysisofvariance(ANOVA)andTukey’sposthocadjustment.

onthermalchangeinthepulpchamberwasinvestigatedwith additionalmeasurementoftheDCanddeliveredenergyden- sityonthetopandbottomsurfacesofthesamples.

Thestudywascarriedoutonarepresentativepermanent molartooth without the use ofanadhesivesystem forall experimentalgroupstoprovidethesametooth-relatedcon- ditionsfor all the measurements and eliminate any effect whichmay arise from structuraland opticaldifferences of the enamel and dentin. The remaining dentin thickness

betweentheinvestigatedmaterialsandthepulpchamberin thepresentinvestigationwas2mm.Although,dentinhasa relatively lowthermalconductivity,thepotentialforpulpal damageisexpectedtobegreaterindeepcavities,wherethe tubularsurfaceareaincreasesandthelightattenuationeffect islower[42–44].Asidefromthedistancebetweenthefloorof thecavityandthepulp,theperfusionrateandeffectofthe pulpalbloodcirculation,thevolumeandmotionofthefluid inthedentinaltubulesaswellasthesurroundingperiodontal

Fig.5–Degreeofconversionatthetopoftheinvestigated materials.The*markindicatesstatisticallysignificant differencebetweentheinvestigatedmaterials.

Fig.6–Degreeofconversionatthebottomofthe investigatedmaterials.The*markindicatesstatistically significantdifferencebetweentheinvestigatedmaterials.

tissuesalsoplayimportantrolesinheatconductionandpro- tectionagainsttheriseofpulpaltemperature[45].According toasimulationstudyonpulpalmicrocirculationconducted byKodonasetal.,theapplicationofathermalstimulussig- nificantlyinfluencestemperaturerise inthepulpchamber.

Resultsshowedatwo-fourtimeshighertemperatureincrease inthe pulpwithoutwaterperfusion[46].Asalimitationof ourstudy,theexperimentaldesignlackedasimulationofthe microcirculation.Althoughthetoothwasimmersedin36.5± 0.5◦Cwaterbathandheldatthistemperatureforthedura- tionofthe study,thisphysiologicaltemperatureisnotable toaccount forall the mechanisms bywhich heat is dissi- patedinvivo.Thereasonwhytheauthorsemployedsucha studydesignwastoillustratethetemperaturechangeswhich arisespecificallyduetotheextentoftheexothermicreaction occurringintheinvestigatedmaterials.

Inthepresentstudy,asecondgenerationLEDLCUwasused toinitiatepolymerizationwitharadiantexitanceof1170±15 mW/cm2atawavelengthrangeof420−480nm.Validpower

measurementsweremadebyacalibratedportableradiome- ter,namelycheckMARC[47],howeverthebeamprofileand surfaceareaoftheactivelighttipwerenotanalysed.Thisis alimitationofourexperimentaldesign,sinceitwasdemon- strated,thatmostoftheLCUs–especiallylowbudgetLCUs, like LED.D–exhibitedhighlynon-homogeneouslightbeam profilesandcouldhaveverydifferentlightoutputcharacter- istics[48,49].Although,thiscouldaffectpulpaltemperature riseandinfluence,especially,DC–evenatdifferentlocations ofthetopandbottomsurfaces–,thesameunitinstandard- izedconditionswasusedtopolymerizeeachmaterialinthe presentstudyandthusenablesthecomparisonoftheresults.

Thepositioningofthelightguidetipwasalsostandardized, ensuringeachsamplereceivedthesamelightbeamcharacter.

Furthermore,thecuringunitpoweredbyalinecordprovided aconstantlightoutputlevel.

TheLCUincreasedthepulpaltemperaturetoadifferent extentthroughtheempty2and4mmdeepmold(6mmin diameter), irradiatedfor20 and 40s, however,the thermal changes(1.9–5.1◦C)didnotexceedthepathologicalthreshold consideredtobe5.5◦CaccordingtoZachandCohenfindings [14].PohtoandScheininalsoreportedthatthecriticaltemper- atureforreversiblepulpdamagewasbetween42◦Cand42.5◦C [50].However,Baldissaraetal.didnotfindanaverageincrease of 11.2 ◦C toaffect the pulpsignificantly [18]. Despite the attemptstodevelopreliablemethodologiestosimulateinvivo condition,awiderangefrom1.5to23.2◦Ctemperaturerise inthepulpchamberwasreportedinvitroduringlightexpo- sure[51].Accordingtoseveralinvestigations,theintensityand duration oftheappliedlightseemedtobethemostcrucial factor inpulpaltemperature rise[15,16,20,46,52,53].Present resultsconfirmthisstatement.Asdemonstratedonconven- tional RBCsan extendedexposureduration(40 s)resulting inadoubledpowerdensityinduced60%highertemperature riseinthepulpchambercomparedtoanirradiationtimeof merely20s.Inspiteoftheimportanceattributedtothecuring lightasapossibleheatsource,itisimportanttoemphasise, thatthelightisattenuatedwithdistance,andthediameter ofthecavityorificealsolimitstheentranceofthe photons whichservenotjustheat,butalsoaselectromagneticenergy fortheprocessofpolymerization[51].Thus,thestrengthof thelightoutputusedinphotopolymerizationcarriesadual importance:ononehand,itshouldbehighenoughtobeable toactivatesufficientfreeradicalstoensureaclinicallyaccept- ablerateofpolymerization,howevernottoohighastoproduce heatdamageinthepulp.Ourresultsshowedthattheradi- antexposureoftheLCUdeliveredthroughthe2and4mm deepemptymoldwith6mmorificediameterwasdecreased by42%and63%,respectively,withanexposuredurationof20 s.Therelatedpulpaltemperatureincreasethroughthe2mm remainingdentinwas1.9and2.7◦C,respectively.However,the heatgeneratedtogetherwiththeexothermicreactionofthe RBCsand conductedtothepulpchamberwashighenough toreachorexceedthecriticaltemperatureatwhichpulpal damagebeginsinalmostallthematerials.Thisisincontrast topreviousstudieswhichshowedthattheheatproducedin anirradiatedemptycavitywasalwayshigherwhencompared tothepolymerizationofa2mmthickcompositeincrement.

Theauthorsattributedtheirresultstotherestorativemate- rial’sattenuatingcapacityagainsttheexothermaleffectofthe

polymerization[15,54].Otherinvestigationshowevershowed thatthebiggestrisktopulphealthoccursduringphotopoly- merization,although,the thermaleffect ofthecuring unit andthematerialdependentexothermicheatproductionisnot separated[37,53].

The maximum temperature values measured ranged between41.4and47.7◦Cinourstudy.Thesedataarecom- parabletotheresultsofotherstudies,wherethegeometryof RBCsaresimilartothatofourspecimens[16].Inthepresent research,thesameLEDunitwith20sdurationwasusedto polymerizethedifferenttypesofinvestigatedmaterials,thus thesameenergydensitywasdeliveredonthetopofeachspec- imen.Thisstudydesigntogetherwiththesingletoothmodel [23] provided uniform conditions allowing to compare the exothermictemperaturerise betweendifferentRBCs.Thus, theexothermicreactionisproportionaltotheamountofresin availableforpolymerization[29,55,56].Accordingtothisstate- ment,because oftheir higher resin content flowable RBCs shouldexhibitahighertemperaturerisethan non-flowable materials.InlinewithBaroudiet al.andAkarsuetal., our findingsalsoconfirmedthatflowableRBCspolymerizewith amoreintenseexothermicreaction[23,38].Ourresultshow- evershowedhighertemperaturerises(5.2–11.2◦C),evenwith aremainingdentinthicknessof2mm.Thereasonforsucha differencemaylieinthestudydesign.Bloodcirculationwas simulatedintheabove-mentionedstudies,whileismissing fromourmethodology.Preparinguniform2mmthicksamples fromalltestedRBCsprovidedresultswhichwerecompara- bleandmadeitpossibletoexaminetheeffectofthevariable compositionofconventional,bulk-fillandSFRCRBCs-forthe same viscosity - onpulpal temperature rise. These results showed thatthe detecteddifferences were significant only betweenbulk-fillandSFRCRBCsinbothviscositieswhilethe conventionalonesproducedsimilartemperaturechangesto thatofbulkandSFRCRBCs.Thecalculationofthepartialeta- squared valuespertainingtofactor materialalso supported thesignificantinfluenceofRBCcompositionontemperature change.

Regardinglayerthickness,statisticallysignificanttemper- aturerisesin4mmcomparedto2mm-thicksampleswere detectedinthebulk-fillandSFRCmaterials.Yasaetal.also foundhighertemperatureriseincaseofthebulk-fillsamples usedin4mm,comparedtotheconventionalRBCwhichwas appliedintwoincrementsof2mmlayers[37].Exothermicdif- ferencesmayariseduetothepresenceofhigheramountsof monomersina4mmthickmaterial.Although,it hasbeen reportedthatincreasedfillercontentcandecreasethetem- peraturerise[57],thechemicallyinertfillersarecapableof absorbingexternalenergy,thusmayplayanindirectrolein thetemperaturerise[58].Moreover,heatgeneratedwithina viscousresin,becomesincreasinglydifficulttoremovewith increasingvolumeoftheresin material[59].Although, our results indicated that higher glass-fiber content increases temperaturerise,incontrasttoourinvestigationIldayetal.did notfindtheadditionofglass-fiberstoinfluencetemperature rise.[60].Comparingthe2mmthickconventionallowviscous RBCtothe2and4mmthicklowviscousbulk-fill,theresults showedinsignificantdifferencescomparedtoourresultsas mentionedabove.Theeffectsizeofthicknessonthethermal changeofRBCsduringpolymerizationwasfoundtobesignif-

icant,howeverithadaweakereffectcomparedtothematerial factor.ThisisincontrastwithParetal.,whosuggestedthat thetemperaturerisewasmostlydeterminedbythevariations ofradiantenergydeliveredtothebottomofthespecimens, hencethecuringunittypeandlayerthicknessplayedmore importantrolesthanthematerialitself[61].Differencesmay havealsoresultedfromthedifferentexperimentalconditions, likethestudydesignforthetemperaturemeasurement,from thetypeoftheLCUused,exposuretimeapplied,thetypeand shadeoftheinvestigatedRBCs,thedimensionsofthespeci- mens,thecoloroftheTeflonmold,etc.

Notonlythedentinthickness,butdifferencesinsurface- to-volumeratiosofvariousresinmaterialscouldaccountfor thedifferencesintheefficiencyofheatdissipation.Thismight bemoreimportantthanthepeaktemperaturewithintheresin [62].

Ourresultsdemonstratedthatthetemperaturecontinues torisealmostlinearlywhilethelightisonreachingthepeak 8–12saftertheexposurewasfinished.Otherauthorsfound thetemperaturerisetooccurassoonasthelightsourcewas activatedandthepeaktemperaturetimetobemainlydepen- dentonthedentinthicknessleftabovethepulpchamber[55].

Runnaclesetal.observedsimilardynamicsinaninvivostudy designtoo,whereT,aswellaspeaktemperatureincreases were continuedtobedetectedforapproximately 10safter teethwereexposedtothelight[63].Thiswasexplainedbythe heat-storingcapacityofdentin[64]whichresultedinagrad- ualdissipationofthermalenergytowardsthepulp,leadingto asustainedtemperatureriseinthepulpchamberevenafter thecuringlightwasshutoff.Additionally,asitwasdiscussed above, the amount of inert filler particles, especially glass fibers,couldhavealsostoredexternal(curinglight)andinter- nal(exothermic)heatenergy[58].Thisfactorwassupported byourpresentfindings,sincehigherfillerloadingresultedin alonger mean timerequiredtoreturnto theinitialpulpal temperature. Inadditiontotheinfluencing effectofdentin thicknessandthepropertiesoftheinvestigatedmaterial,the studydesignalsoplaysasignificantroleonheatdissipation whichmakesitdifficulttocomparedifferentresearchfind- ings.

PohtoandScheininnotedthatthedurationofthethermal irritationisanotherfactorinpulpaldamage,since2minat 46◦Ccancauseanarrestofbloodcirculation[50].According toourmeasurements,thetimeittookforthetemperatureto returntotheinitialrangedbetween95.0–404.6s.Eventhough themaximumtemperaturedetectedinhigh-viscositymate- rials waslower thaninlow-viscosityRBCs,theytookmore timetocooldown.Thepulpaltemperaturehoweverdecreased below42◦Cwithin80sinallcases,evenwithoutsimulation ofthepulpalcirculation.

Regardingtheradiantenergymeasuredatthebottomof thesamples,valueswere54–92%lowerthantheincidentradi- antenergymeasuredatthetopofthe2-and4-mmthickRBC samples.Thelightattenuationwasstronglyinfluencedbythe materialcomposition,shadeandthickness.Previousstudies haveshownthatfactorssuchaspolymericmatrixrefractive index,monomertype,fillertype,loadingandsizecaninflu- encelighttransmittanceinRBCs[65,66].Higherfillercontent andthickersamplesdecreasedradiantenergyradically,while amoretranslucentshadeandhigherglass-fibercontentpro-

videdforahigherradiantenergylevelatthebottomofthe4 mmthicksamplesascomparedtothe2mmthick,A2shaded materials.ThiswasinlinewithGaroushietal.,whoalsofound moretranslucent bulk-fillsand shortfiber-reinforced RBCs withbulkshade(universalshade)toallowforahigherlight transmissioncomparedtotheconventionalresincomposites [35].Although,thefillerratioofFiltekSupremeFlowableisthe lowestamongthetestedRBCs,thelightattenuationthrough the2mmthick samplewas 82%.Inspitethe factthatthe morepigmentedA2shadeofthismaterialandthequalityof thefillerparticles(Zr-silicaclusters)mayexhibithigherlight distribution withinthe material, the monomer to polymer conversionstillreachedahighdegree.Itiswell-documented, thatradiant exposureundoubtedly influencesthe DC [1,5], however,thepolymerizationkineticshavebeenfoundtobe highlycomplex,and irradiance,exposureand composition canindependentlyaffecttheDC[58,67].BucutaandIliefound microhardnesstobeabove80%whentheenergymeasured atthebottomofthesampleswaslargerthan0.7J/cm2.While theincreasewasproportionaltotheamountoftransmitted light,theyalsofoundthefillercontenttohaveahighereffect ontheresultscomparedtothe transmittedirradiance[11].

OurresultsdemonstratedthesametendencyforDC-which hasastrongcorrelationwithhardness[68]-,sincethelowest DCwasmeasuredwithmeanradiantenergyof0.7J/cm2(Fil- tekOneBulkRBCin4mmthickness)androsewithincreasing lighttransmittance.AccordingtoShortalletal.’sfindings,indi- vidualproductsrequiredifferentlevelsofradiantexposureto provideoptimalproperties[25].

Thedegreeofconversionatthetopandbottomsurfaces ofthedifferentRBCswereassessedusingmicro-Ramanspec- troscopywhichallowsthedirectdetectionoftheamountof unreactedC Cintheresinmatrix[58].Raman-spectrawere takenafter24h,sincesignificantincreaseinDCtakesplace evenaftertheremovaloftheirradiationsource,uptoamax- imum of24 hpost-irradiation [69]. Regarding conventional RBCs,the2mmthickflowablesamplereachedahighdegreeof conversionwithoutsignificantdifferencebetweenthetopand bottomsurfacesirrespectiveofwhethertherecommendedor doubledexposuretimewasapplied.ThisRBChasthe low- estfillercontentamongtheinvestigatedmaterials.Halvorson etal.demonstrated,thatincreasingthe fillerratio progres- sivelydecreasesconversion,becauseanincreasedamountof fillerparticlesisanobstacletopolymerpropagation[70].Sim- ilarDCvaluesweredetectedinthe2mmthicklowviscous bulk-fillandthelowandhighviscousSFRCs.Lightpenetra- tionthroughthe2mmSFRCsampleswashigher,whichmay beexplainedbythemoretranslucentglassfillersandfibers.

SFRCmaterials(EverXPosteriorandFlow)areuniqueamong theotherscontainingrandomlyorientedshortglassfibersin mmscale.Thehightranslucencyoftheglassfibersmayhave increasedlightpenetrationindeeperregionsresulting ina higherdegreeofconversion.Thisisinlinewiththefindings ofGaroushietal.andGoraccietal.[35,71].Although,theshort glassfibercontentincreasedto25%intheflowableEverXcom- paredtothe9%ofthehighviscousEverXPosterior,theDC andthelighttransmittancedidnotincreasesignificantly.The temperaturerisehoweverwasmorepronounced[72].Consid- eringthemonomercontentoftheinvestigatedRBCs,itmay alsobe assumed,that the higher DC values are attributed

totheTEGDMA monomer,whichisacomponentofall the testedlow-viscosityRBCsandthehigh-viscositySFRC.Besides decreasingviscosity,thelowmolecularweightofTEGDMAas wellastheether(C O C)linkage,providingaslightrotation aroundthebond,allowsformorecovalentbondstobecreated duringthepolymerization[73].

Incontrasttotheresultsmentionedabove,significantdif- ferenceswerefoundbetweenthetopandbottomDCsincases ofthe2mmthick highviscosityconventional andbulk-fill RBCsandinallthe4mmthicksamplesofhigh-andlowvis- cositybulk-fillandSFRCmaterials.While,theDCvaluesat thebottomsurfacesofthe4mmthicksamplesfailedtoreach the valuesmeasuredonthe top,theSFRCRBCsreachedor exceededtheresultsfoundatthebottomofthe2mmthick conventionalhighlyviscousRBCscuredfor20sandeven40 s.Theconsequenceofthelowerrateoflightattenuationin SFRCswasseeninthehigherDCvalues,whilethehighgrade ofphoton-attenuatingcapacityofthehighviscosityconven- tional and bulk-fillRBCs isalsoclearly reflected inthe DC results.Thehigheramountofparticulatefillercontentofthe highlyviscousconventional(FiltekZ250)andbulk-fill(Filtek OneBulkFill)RBCsexplainsthereducedlighttransmittance and theconsequentiallowerDC atthe bottomofthesam- ples[65,69].Inaddition, theincorporationofthefillerscan restrictthemobilityofthemonomersand radicals,leading toadecreasedconversion[73].Lowerconversion,maycom- promisethemechanicalpropertiesandthebiocompatibility oftheRBC,leadingtolowervaluesofhardness,earlydegra- dation of the RBC and release offree monomers, which – togetherwiththethermalload-canfurtherincreasethehaz- ardofpulpaldamage[32,34,74].Although,theminimumDC foraclinicallysatisfactoryrestorationhasnotyetbeenestab- lished,negativecorrelationwithinvivoabrasiveweardepth wasfoundforDCvaluesintherangeof55–65%[75,76].Asa flowablebulk-fillRBC,universal-shadeofSurefilSDRFlow+

wasinvestigatedinthepresentstudy,whichisanimproved versionofthewell-knownSurefilSDRFlow.Itwasdeveloped toincrease themechanicalproperties, wearresistanceand radiopacity[77].Severalresearchesprovedthehighconver- siondegreeoftheuniversal-shadeSurefilSDRFlow,evenin aneight-mmdeepcavity,wheretheDCreached63%afteran exposuretimeof20swithoutasignificantdifferencebetween thetopandbottomsurfaces[58].However,ourresultsdemon- stratedalowerDC%atthebottominthenewlydevelopedSDR Flow+,eventhoughthesamplewasirradiatedfromadistance ofzerobetweenthetopandlightguidetip.SDRFlow+contains 2.5%morefillercontentwithradiopacifiers,aswellasamod- ifiedmonomercomposition,whencomparedtotheinitially developedSurefilSDRFlow.Thismaycontributetothelower degreeofconversion.

Thelowestdegreeofconversion(52%)wasmeasuredinthe high-viscositybulk-fillRBC(FiltekOneBulkFill).Theexplana- tionforthiscannotjustbefoundinthehigherparticulatefiller loadand thepresenceofZr-silicaclusters,butmay alsobe explainedbythecontentofadditionfragmentationmonomers (AFM),incorporatedintotheresinmatrixasastressreliever.

Shahetal.demonstrated,thattheincorporationofAFM may leadtoagradual reductioninpolymerization kinetics alongwithasteadydecreaseofthereactionrateresultingin alowerconversionoftheRBC[78].TheDC-reducingpowerof

thismonomerissignificantabove5wt.%,howevertheexact contentofAFMisatradesecret.

Thisstudyhassomelimitationssuchastheremovalofthe enamelanddentinwalls,lackofapplicationofanadhesive layer,andmeasurementoftheintrapulpaltemperaturefroma singlepointwithoutsimulationofthebloodmicrocirculation.

Inthepresenceofaxialenamelanddentinwalls,theintrapul- paltemperatureincreasemaybemorerestrainedduetoheat dissipation.Alternatively,duetotheheat-storingcapacityof thedentinontopofthepulpchamber,theremaybeagrad- ualdissipationofthermalenergytowardthepulp,leadingto asustainedhighertemperatureinthepulpchamber[64],as observedinourstudy.Thus,theimportanceoftheremaining dentinthicknessabovethepulpchamberistwofold:whenitis decreased,boththeinsulatingeffectandheat-storingcapacity aredecreased.

Inaddition,thepolymerizedadhesivelayermayserveas abarriertoheattransferunderclinicalconditions.However, onemust considerthatduringpolymerizationofthe adhe- sivelayer,itwasfoundthatthepulptemperatureincreased fasterthanduringthephotocuringoftheRBC,especiallywith anirradiancehigherthan1000mW/cm2[79].Basedonthis observation,animportantproblemmayarisefromtheimme- diateapplicationoftheRBCwithoutfirstallowingforheatto dissipate.HeatgeneratedbytheirradiationoftheRBCcould potentiallycompoundintrapulpalthermaldamageasthepul- palanddentinetemperaturesarealreadyhigherduetothe adhesivepolymerization.

Moreover,thesimulationofbloodcirculationcandecrease theintrapulpaltemperatureinvitroasitmayhappeninvivo.

Although, heat dissipation is strongly influenced by blood circulation,Runnaclesetal.concluded,thatthepulpaltem- peratureincreasevaluesmeasuredinvitrowerecomparable totheinvivovalueswhenclinicallyrelevantlightexposure modes were compared [17]. Bone simulation experiments investigatingdrilling-inducedheatgenerationhavealsofound bloodcirculationtohavealowerimpactontemperatureaccu- mulation[80,81].

Regardingthelayerthickness,asalimitationofthisstudy, conventionalRBCswere nottestedinathicknessof4mm.

Although,itwouldhaveprovidedmoredatatoestimatethe effectsize ofthe investigatedvariables,conventional RBCs arerecommendedtobeappliedinamaximumthicknessof 2mm-aspermanufacturer’sinstructions-thustheauthors consideredtesting themin4mmthickness nottoberele- vant.

Although, bulk-fill RBCs can achieve a higher depth of curethanconventionalRBCs,thedepthofcureisnotalways clinicallyacceptableatathicknessof4mmwhenexposed as per manufacturer’s instructions (i.e. 10–20 s) [82]. As a limitationitshouldbementionedthatthepresentstudyinves- tigatedtheDCsandPTschangesofconventionalRBCswithan extendedexposuretime,whilebulk-fillandSFRCRBCswere testedonlywithanexposuredurationof20s.Severalinves- tigationsdemonstrated ahigherDC ofbulk-fillsand SFRCs withanextendedirradiationtime[82,83].Itseffectpertaining tobulk-fillshoweverisstronglymaterialdependent[10,58].

Eventhoughincreasedirradiationtimeisproventobebene- ficialformechanicalproperties[10],itmayalsoincreasethe pulpaltemperaturetherebycompromisingthehealthofthe

pulptissue.Furtherinvestigationsarerequiredtoclarifythis assumption.

Lastly,thepresentstudydidnotevaluatetheeffectsofthe different,clinicallymorerelevantcavitydesigns(depth,ori- fice diameter, remainingdentinthickness)whichmay also significantlyimpactdeliveredenergydensity,DCandpulpal temperature.

5. Conclusion

Withinthelimitationsofthisinvitrostudy,thefollowingcon- clusionscanbestated:

1) ThetemperatureandDCvalueswerepredominantlyinflu- encedbythecompositionofthematerialfollowedbythe thickness.

2) Thelow-viscosityRBCsand thematerialsusedin4mm thickness increased the pulpal temperature by a sig- nificantly higher extent. Amongthe different groupsof materials,themoretranslucentSFRCRBCsshowedsignif- icantlyhighertemperaturechange.

3) SignificantlyhigherDC levelswere measuredatthe top ofthesamplesascomparedtothebottominthe 2mm thickhigh-viscosityconventionalandbulk-fillRBCsandin each4mmthickhigh-andlow-viscositymaterials.Among thedifferentgroupsofmaterials,theconventionalflowable andtheSFRCRBCsachievedhigherDClevels.

4) Doublingthe exposuretimeincreasedsignificantlyboth theintrapulpal temperatureaswell asDCvaluesofthe investigatedconventionalRBCs.

5) HigherDCvaluesareassociatedwithsignificantincrease inpulpaltemperature,whichshouldbeconsideredbythe clinicianswhentheywanttoachievehigherDC%forbetter clinicalperformanceoftherestoration.

Acknowledgments

ThisworkwassupportedbytheBolyaiJánosResearchSchol- arship(BO/713/20/5);theÚNKP-20-5NewNationalExcellence ProgramoftheMinistryforInnovationandTechnologyfrom theSourceoftheNationalResearch,DevelopmentandInno- vationFund(ÚNKP-20-5-PTE-615),PTE-ÁOK-KA-2020/24and GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00049ResearchGrant.

references

[1] HalvorsonRH,EricksonRL,DavidsonCL.Energydependent polymerizationofresin-basedcomposite.DentMater 2002;18:463–9.

[2] LempelE,CzibulyaZ,Kunsági-MátéS,SzalmaJ,SümegiB, BöddiK.Quantificationofconversiondegreeandmonomer elutionfromdentalcompositeusingHPLCand

micro-Ramanspectroscopy.Chromatographia 2014;77:1137–44.

[3] AlShaafiMM.Factorsaffectingpolymerizationof resin-basedcomposites:aliteraturereview.SaudiDentJ 2017;29:48–58.

[4] RueggebergFA,CaughmanWF,CurtisJrJW.Effectoflight intensityandexposuredurationoncureofresincomposite.

OperDent1994;19:26–32.

[5] EmamiN,SöderholmKJ.Howlightirradianceandcuring timeaffectmonomerconversioninlight-curedresin composites.EurJOralSci2003;111:536–42.

[6] NeumannMG,MirandaWG,SchmittCC,RueggebergFA, CorreaIC.Molarextinctioncoefficientsandthephoton absorptionefficiencyofdentalphotoinitiatorsandlight curingunits.JDent2005;33:325–32.

[7] FengL,CarvalhoR,SuhBI.Insufficientcureunderthe conditionofhighirradianceandshortirradiationtime.Dent Mater2009;25:283–9.

[8] AlshaliRZ,SalimNA,SungR,SatterthwaiteJD,SilikasN.

Analysisoflong-termmonomerelutionfrombulk-filland conventionalresin-compositesusinghighperformance liquidchromatography.DentMater2015;31:1587–98.

[9] MoldovanM,BalazsiR,SoancaA,RomanA,SarosiC,Prodan D,etal.Evaluationofthedegreeofconversion,residual monomersandmechanicalpropertiesofsomelight-cured dentalresincomposites.Materials2019;12:2109.

[10] IlieN,KeßlerA,DurnerJ.Influenceofvariousirradiation processesonthemechanicalpropertiesandpolymerisation kineticsofbulk-fillresinbasedcomposites.JDent

2013;41:695–702.

[11] BucutaS,IlieN.Lighttransmittanceandmicro-mechanical propertiesofbulkfillvs.conventionalresinbased

composites.ClinOralInvestig2014;18:1991–2000.

[12] KrämerN,LohbauerU,Garcia-GodoyF,FrankenbergerR.

Lightcuringofresin-basedcompositesintheLEDera.AmJ Dent2008;21:135–42.

[13] SeligD,HaenelT,HausnerovaB,MoegingerB,LabrieD, SullivanB,etal.Examiningexposurereciprocityinaresin basedcompositeusinghighirradiancelevelsandreal-time degreeofconversionvalues.DentMater2015;31:583–93.

[14] ZachL,CohenG.Pulpresponsetoexternallyappliedheat.

OralSurgOralMedOralPathol1965;19:515–30.

[15] LeprinceJ,DevauxJ,MullierT,VrevenJ,LeloupG.

Pulpal-temperatureriseandpolymerizationefficiencyof LEDcuringlights.OperDent2010;35:220–30.

[16] HannigM,BottB.In-vitropulpchambertemperaturerise duringcompositeresinpolymerizationwithvarious light-curingsources.DentMater1999;15:275–81.

[17] RunnaclesP,ArraisCAG,MaucoskiC,CoelhoU,DeGoesMS, RueggebergFA.Comparisonofinvivoandinvitromodelsto evaluatepulptemperatureriseduringexposuretoa Polywave®LEDlightcuringunit.JApplOralSci 2019;27:e20180480.

[18] BaldissaraP,CatapanoS,ScottiR.Clinicalandhistological evaluationofthermalinjurythresholdsinhumanteeth:a preliminarystudy.JOralRehabil1997;24:791–801.

[19] UhlA,VolpelA,SiguschBW.Influenceofheatfromlight curingunitsanddentalcompositepolymerizationoncells invitro.JDent2006;34:298–306.

[20] JakubinekMB,O’NeillC,FelixC,PriceRB,WhiteMA.

Temperatureexcursionsatthepulp-dentinjunctionduring thecuringoflight-activateddentalrestorations.DentMater 2008;24:1468–76.

[21] KwonSJ,ParkYJ,JunSH,AhnJS,LeeIB,ChoBH,etal.

Thermalirritationofteethduringdentaltreatment procedures.RestorDentEndod2013;38:105–12.

[22] LloydCH,JoshiA,McGlynnE.Temperatureriseproducedby lightsourcesandcompositesduringcuring.DentMater 1986;2:170–4.

[23] BaroudiK,SilikasN,WattsDC.Invitropulpchamber temperaturerisefromirradiationandexothermofflowable composites.IntJPaediatrDent2009;19:48–54.

[24] GoodisHE,WhiteJM,GammB,WatanabeL.Pulpchamber temperaturechangeswithvisible-light-curedcompositesin vitro.DentMater1990;6:99–102.

[25] ShortallA,El-MahyW,StewardsonD,AddisonO,PalinW.

Initialfractureresistanceandcuringtemperatureriseoften contemporaryresin-basedcompositeswithincreasing radiantexposure.JDent2013;41:455–63.

[26] YaziciAR,MuftuA,KugelG,PerryRD.Comparisonof temperaturechangesinthepulpchamberinducedby variouslightcuringunits,invitro.OperDent2006;31:261–5.

[27] OzturkB,OzturkAN,UsumezA,UsumezS,OzerF.

Temperatureriseduringadhesiveandresincomposite polymerizationwithvariouslightcuringsources.OperDent 2004;29:325–32.

[28] KimMJ,KimRJY,FerracaneJ,LeeIB.Thermographicanalysis oftheeffectofcompositetype,layeringmethod,andcuring lightonthetemperatureriseofphoto-curedcompositesin toothcavities.DentMater2017;33:e373–83.

[29] Al-QudahA,MitchellC,BiagioniPA,HusseyDL.Effectof compositeshade,incrementthicknessandcuringlighton temperatureriseduringphotocuring.JDent2007;35:238–45.

[30] AtaiM,AhmadiM,BabanzadehS,WattsDC.Synthesis, characterization,shrinkageandcuringkineticsofanew low-shrinkageurethanedimethacrylatemonomerfor dentalapplication.DentMater2007;23:1030–41.

[31] WattsDC,McAndrewR,LloydCH.Thermaldiffusivityof compositerestorativematerials.JDentRes1987;66:1576–8.

[32] FronzaBM,RueggebergFA,BragaRR,MogilevychB,Soares LES,MartinAA,etal.Monomerconversion,microhardness, internalmarginaladaptation,andshrinkagestressof bulk-fillresincomposites.DentMater2015;31:1542–51.

[33] IlieN,StarkK.Curingbehaviourofhigh-viscositybulk-fill composites.JDent2014;42:977–85.

[34] LempelE,CzibulyaZ,KovácsB,SzalmaJ,TóthÁ, Kunsági-MátéS,etal.DegreeofconversionandBisGMA, TEGDMA,UDMAelutionfromflowablebulk-fillcomposites.

IntJMolSci2016;17:732.

[35] GaroushiS,VallittuP,ShinyaA,LassilaL.Influenceof incrementthicknessonlighttransmission,degreeof conversionandmicrohardnessofbulkfillcomposites.

Odontology2016;104:291–7.

[36] KimRJY,SonSA,HwangJY,LeeIB,SeoDG.Comparisonof photopolymerizationtemperatureincreasesininternaland externalpositionsofcompositeandtoothcavitiesinreal time:incrementalfillingsofmicrohybridcompositevs.bulk fillingofbulkfillcomposite.JDent2015;43:1093–8.

[37] YasaE,AtalayinC,KaracolakG,SariT,TürkünLS.

Intrapulpaltemperaturechangesduringcuringofdifferent bulk-fillrestorativematerials.DentMaterJ2017;36:566–72.

[38] AkarsuS,KarademirSA.Influenceofbulk-fillcomposites, polimerizationmodes,andremainingdentinthicknesson intrapulpaltemperaturerise.BiomedResInt2019:4250284.

[39] LempelE,TóthÁ,FábiánT,KrajczárK,SzalmaJ.

Retrospectiveevaluationofposteriordirectcomposite restorations:10-yearfindings.DentMater2015;31:115–22.

[40] GaroushiS,SäilynojaE,VallittuPK,LassilaL.Physical propertiesanddepthofcureofanewshortfiberreinforced composite.DentMater2013;29:835–41.

[41] FráterM,ForsterA,KeresztúriM,BraunitzerG,NagyK.

Invitrofractureresistanceofmolarteethrestoredwitha shortfibre-reinforcedcompositematerial.JDent 2014;42:1143–50.

[42] LinM,XuF,LuTJ,BaiBF.Areviewofheattransferinhuman tooth–experimentalcharacterizationandmathematical modeling.DentMater2010;26:501–13.

[43] NakajimaM,ArimotoA,PrasansuttipornT,Thanatvarakorn O,FoxtonRM,TagamiJ.Lighttransmissioncharacteristicsof

dentineandresincompositeswithdifferentthickness.J Dent2012;40:e77–82.

[44] PriceRB,MurphyDG,DerandT.Lightenergytransmission throughcuredresincompositeandhumandentin.

QuintessenceInt2000;31:659–67.

[45] RaabWH.Temperaturerelatedchangesinpulpal microcirculation.ProcFinnDentSoc1992;88:469–79.

[46] KodonasK,GogosC,TziafasD.Effectofsimulatedpulpal microcirculationonintrapulpaltemperaturechanges followingapplicationofheatontoothsurfaces.IntEndodJ 2009;42:247–52.

[47] ShortallAC,FelixCJ,WattsDC.Robustspectrometer-based methodsforcharacterizingradiantexitanceofdentalLED curingunits.DentMater2015;31:339–50.

[48] ShimokawaCAK,TurbinoML,HarlowJE,PriceHL,PriceRB.

Lightoutputfromsixbatteryoperateddentalcuringlights.

MaterSciEngCMaterBiolAppl2016;69:1036–42.

[49] AlShaafyMM,HarlowJE,PriceHL,RueggebergFA,LabrieD, AlQahtaniMQ,etal.Emissioncharacteristicsandeffectof batterydrainin“budget”curinglights.OperDent 2016;41:397–408.

[50] PohtoM,ScheininA.Microscopicobservationsonliving dentalpulpII.Theeffectofthermalirritantsonthe circulationofthepulpinthelowerratincisor.ActaOdontol Scand1958;16:315–27.

[51] RueggeberFA,GianniniM,ArraisCAG,PriceRBT.Light curingindentistryandclinicalimplications:aliterature review.BrazOralRes2017;31:e61.

[52] AsmussenE,PeutzfeldtA.Temperatureriseinducedby somelightemittingdiodeandquartz-tungsten-halogen curingunits.EurJOralSci2005;113:96–8.

[53] DaronchM,RueggebergFA,HallG,DeGoesMF.Effectof compositetemperatureoninvitrointrapulpaltemperature rise.DentMater2007;23:1283–8.

[54] ShortallAC,HarringtonE.Temperatureriseduring polymerizationoflight-activatedresincomposites.JOral Rehabil1998;25:908–13.

[55] Al-QudahAA,MitchellCA,BiagioniPA,HusseyDL.

Thermographicinvestigationofcontemporary resin-containingmaterials.JDent2005;33:593–602.

[56] EmamiM,SöderholmKJ,BerglundLA.Effectoflightpower densityvariationsonbulkcuringpropertiesofdental composites.JDent2003;31:189–96.

[57] AtaiM,MotevasselianF.Temperatureriseanddegreeof photopolymerizationconversionofnanocompositesand conventionaldentalcomposites.ClinOralInvestig 2009;13:309–16.

[58] LempelE, ˝OriZ,SzalmaJ,LovászVB,KissA,TóthÁ,etal.

Effectofexposuretimeandpre-heatingontheconversion degreeofconventional,bulk-fill,fiberreinforcedand polyacid-modifiedresincomposites.DentMater 2019;35:217–28.

[59] CioffiM,HoffmannAC,JanssenLPBM.Reducingthegel effectinfreeradicalpolymerization.ChemEngSci 2001;56:911–5.

[60] IldayNO,SagsozO,KaratasO,BayindirYZ,CelikN.

Temperaturechangecausedbylightcuringof fiber-reinforcedcompositeresins.JConservDent 2015;18:223–6.

[61] ParM,RepusicI,SkenderovicH,MilatO,SpajicJ,TarleZ.The effectsofextendedcuringtimeandradiantenergyon microhardnessandtemperatureriseofconventionaland bulk-fillresincomposites.ClinOralInvestig2019;23:3777–88.

[62] VallittuPK.Peaktemperaturesofsomeprostheticacrylates onpolymerization.JOralRehabil1996;23:776–81.

[63] RunnaclesP,ArraisCAG,PochapskiMT,dosSantosFA, CoelhoU,GomesJC,etal.Invivotemperaturerisein

anesthetizedhumanpulpduringexposuretoapolywave LEDlightcuringunit.DentMater2015;31:505–13.

[64] ChiangYC,LeeBS,WangYL,ChengYA,ChenYL,ShiauJS, etal.Microstructuralchangesofenamel,dentin-enamel junction,anddentininducedbyirradiatingouterenamel surfaceswithCO2laser.LasersMedSci2008;23:41–8.

[65] dosSantosGB,AltoRV,FilhoHR,daSilvaEM,FellowsCE.

Lighttransmissionondentalresincomposites.DentMater 2008;24:571–6.

[66] EmamiN,SjödahlM,SoderhölmK-JM.Howfillerproperties, fillerfraction,samplethicknessandlightsourceaffectlight attenuationinparticulatefilledresincomposites.Dent Mater2005;21:721–30.

[67] DoughertyMM,LienW,MansellMR,RiskDL,SavettDA, WandewalleKS.Effectofhigh-intensitycuringlightsonthe polymerizationofbulk-fillcomposites.DentMater

2018;34:1531–41.

[68] FerracaneJL.Correlationbetweenhardnessanddegreeof conversionduringthesettingreactionofunfilleddental restorativeresins.DentMater1985;1:11–4.

[69] AlshaliRZ,SilikasN,SatterthwaiteJD.Degreeofconversion ofbulk-fillcomparedtoconventionalresin-compositesat twotimeintervals.DentMater2013;29:e213–7.

[70] HalvorsonRH,EricksonRL,DavidsonCL.Theeffectoffiller andsilanecontentonconversionofresin-basedcomposite.

DentMater2003;19:327–33.

[71] GoracciC,CadenaroM,FontaniveL,GiangrossoG,JuloskiJ, VichiA,etal.Polymerizationefficiencyandflexuralstrength oflow-stressrestorativecomposites.DentMater

2014;30:688–94.

[72] GCAustralia,EverXFlow2019

http://www.gcaustralasia.com/Upload/product/pdf/112/

F575EverX-Flow-brochureFinalWS17052019.pdf.[Accessed 23October2020].

[73] Amirouche-KorichiA,MouzaliM,WattsDC.Effectsof monomerratiosandhighlyradiopaquefillersondegreeof conversionandshrinkage-strainofdentalresincomposites.

DentMater2009;25:1411–8.

[74] LovászBV,LempelE,SzalmaJ,SétálóJrG,VecsernyésM, BertaG.InfluenceofTEGDMAmonomeronMMP-2,MMP-8, andMMP-9productionandcollagenaseactivityinpulp cells.ClinOralInvestig2020,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03545-5.Epubaheadof print.

[75] FerracaneJL,MitchemJC,CondonJR,ToddR.Wearand marginalbreakdownofcompositeswithvariousdegreesof cure.JDentRes1997;76:1508–16.

[76] SilikasN,EliadesG,WattsDC.Lightintensityeffecton resin-compositedegreeofconversionandshrinkagestrain.

DentMater2000;16:292–6.

[77] DentsplySirona,SDRFlow+BulkFillFlowable2017 https://assets.dentsplysirona.com/flagship/en/explore/

restorative/sdrflowpluseuversion/SM%20SDR%20Flow Plus%20V01%202017-12-08.pdf.[Accessed23October2020].

[78] ShahPK,StansburyJW,BowmanCN.Applicationofan addition-fragmentation-chaintransfermonomerin di(meth)acrylatenetworkformationtoreduce polymerizationshrinkagestress.PolymChem 2017;8:4339–51.

[79] MillenC,OrmonM,RichardsonG,SantiniA,MileticV,KewP.

Astudyoftemperatureriseinthepulpchamberduring compositepolymerizationwithdifferentlightcuringunits.J ContempDentPract2007;8:29–37.

[80] PandeyRK,PandaSS.Drillingofbone:acomprehensive review.JClinOrthopTrauma2013;4:15–30.

[81] SzalmaJ,LovászBV,VajtaL,SoósB,LempelE,Möhlhenrich C.Theinfluenceofthechoseninvitrobonesimulation

modelonintraosseoustemperaturesanddrillingtimes.Sci Rep2019;9:11817.

[82] RodriguezA,YamanP,DennisonJ,GarciaD.Effectof light-curingexposuretime,shade,andthicknessonthe depthofcureofbulkfillcomposites.OperDent 2017;42:505–13.

[83] JangJH,ParkSH,HwangIN.Polymerizationshrinkageand depthofcureofbulk-fillresincompositesandhighlyfilled flowableresin.OperDent2015;40:172–80.