https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098619854014 https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098619854014

Ther Adv Drug Saf 2019, Vol. 10: 1–22 DOI: 10.1177/

2042098619854014

© The Author(s), 2019.

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals- permissions

Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

journals.sagepub.com/home/taw 1

and inappropriate medication use

Introduction

Polypharmacy and high-risk prescribing are highly prevalent in the older population. One of the core strategies how to reduce these negative phenom- ena are pharmacist- or physician-led medication reviews, and the process of deprescribing.

Deprescribing has been defined as ‘…withdrawal of inappropriate medication, supervised by a

healthcare professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving older patient safety and health outcomes.’1 Many different tools have been developed for deprescribing [e.g. different geriatric risk scores, geriatric tools enabling identi- fication of anticholinergic and sedative drug bur- den, implicit prescribing algorithms or explicit criteria of potentially inappropriate medications

Applicability of EU(7)-PIM criteria in

cross-national studies in European countries

Daniela Fialová ,Jovana Brkić, Blanca Laffon, Jindra Reissigová, Silvia Grešáková, Soner Dogan, Peter Doro, Ljiljana Tasić, Valentina Marinković, Vanessa Valdiglesias, Solange Costa and Jan Kostřiba

Abstract

Background: The European Union (EU)(7)-PIM (potentially inappropriate medication) list presents the most comprehensive and up-to-date tool for evaluation of PIM prescribing in Europe; however, several country-specific studies have documented lower specificity of this list on pharmaceutical markets of some countries. The aim of our study was to describe approval rates and marketing of PIMs stated by EU(7)-PIM criteria in six EU countries [in comparison with the American Geriatric Society (AGS) Beers 2015 criteria].

Methods: Research teams of six EU countries (Czech Republic, Spain, Portugal, Serbia, Hungary and Turkey) participated in this study conducted by WG1b EU COST Action IS1402 group in the period October 2015–November 2018. Data on approval rates of PIMs and their availability on pharmaceutical markets have been obtained from databases of national drug- regulatory institutes and up-to-date drug compendia. The EU(7)-PIM list and AGS Beers 2015 Criteria (Section 1) were applied.

Results: PIMs from EU(7)-PIM list were approved for clinical use more often than those from the AGS Beers 2015 criteria (Section 1). Approval rates for EU(7)-PIMs ranged from 42.8%

in Serbia to 71.4% in Spain (for AGS criteria only from 36.4% to 65.1%, respectively). Higher percentages of approved PIMs were documented in Spain (71.4%), Portugal (67.1%) and Turkey (67.5%), lower in Hungary (55.5%), Czech Republic (50.2%) and Serbia (42.8%). The majority of approved PIMs were also currently marketed in all countries except in Turkey (19.8–21.7% not marketed PIMs) and less than 20% of PIMs were available as over-the- counter medications (except in Turkey, 46.4–48.1%).

Conclusions: The EU(7)-PIM list was created for utilization in European studies; however, applicability of this list is still limited in some countries, particularly in Eastern and Central Europe. The EU project EUROAGEISM H2020 (2017–2021) that focuses on PIM prescribing and regulatory measures in Central and Eastern European countries must consider these limits.

Keywords: aged, geriatrics, PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications, regulatory measures

Received: 10 December 2018; revised manuscript accepted: 24 April 2019.

Correspondence to:

Daniela Fialová Department of Social and Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Králové, Charles University, Heyrovského 1203, Hradec Králové 500 05, Czech Republic Department of Geriatrics and Gerontology, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic daniela.fialova@lf1.cuni .cz; daniela.fialova@faf .cuni.cz

Jovana Brkić Silvia Grešáková Jan Kostřiba Department of Social and Clinical Pharmacy, Charles University, Czech Republic

Blanca Laffon Vanessa Valdiglesias DICOMOSA Group, Department of Psychology, Universidade da Coruña, A Coruña, Spain

Jindra Reissigová Department of Statistical Modeling, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic Soner Dogan Department of Medical Biology, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey

Peter Doro Department of Clinical Pharmacy, University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary Valentina Marinković Ljiljana Tasić Department of Social Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Legislation, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia Solange Costa

Department of Environmental Health, Portuguese National Institute of Health, Porto, Portugal

EPIUnit, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Original article

(so called PIMs)].2 The latter are older and sim- pler tools, now more used in clinical practice and research.

The first explicit criteria of PIMs have been pub- lished already 20 years ago (Beers 1991 criteria)3 and the newest, extensive lists of PIMs applied in international research are (a) the American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria (AGS Beers crite- ria, with the previous version published in 2015,4 now newly updated in January 2019),5 (b) the STOPP/START 2015 criteria (version 2),6 and (c) the European Union (EU)(7)-PIM list from 2015.7 While the EU (7)-PIM list and Section 1 of the AGS Beers criteria state PIMs mostly disre- gard clinical conditions of inappropriateness and may be applied in regulatory studies, the applica- tion of STOPP/START criteria require clinical information on results of patients’ clinical assess- ments and lab tests and these criteria are specifi- cally designed for identification of PIMs in clinical practice.4–7 Of the three above-stated criteria, the EU(7)-PIM list is the first multicentric European tool developed by experts from seven EU coun- tries, namely from Estonia, Netherlands, Finland, Spain, France, Sweden and Denmark.7 However, in national research and clinical practice, mostly higher specificity of national tools have been confirmed, for example, of Laroche’s criteria in France,8 NORGEP9 and NORGEP-NH criteria in Norway,10 the PRISCUS list in Germany,11 and McLeod’s12 and Rancourt’s criteria in Canada,13 etc. These tools have been developed for specific national studies by excluding PIMs not approved on country-specific pharmaceutical markets and by inserting ‘new PIMs’ available only in a spe- cific country. For these reasons, applicability of national criteria in the international context is limited.

Sufficient numbers of studies confirmed serious negative outcomes of PIMs, for example, increase in the prevalence of geriatric symptoms and syn- dromes (drug-related bradycardias, renal insuffi- ciency, cognitive impairment, deliria, drug-related malnutrition, falls, etc.), increase in number and length of hospitalizations, worsening of geriatric frailty, higher utilization of healthcare services and costs, and also increase in mortality in several stud- ies.14–19 However, despite much evidence on nega- tive outcomes, prescribing of PIMs is still high in the older population and varies significantly across different settings of care, facilities, regions, and countries. As confirmed by two systematic reviews,

the weighted point prevalence of PIM use in European studies was 49.0% in institutional care and 22.6% in community-residing older adults.20,21 The US study by Jiron et al. described the decrease in PIM prevalence from 64.9% to 56.6% between 1997 and 2012, respectively.22 However, the Irish study found the increase in the prevalence from 32.6% to 37.3% in the same period.23 It is well known that PIM prescribing is also strongly influ- enced by prescribing habits, different perceptions of physicians on inappropriateness of PIMs, differ- ent country-specific recommendations, guidelines and regulations.

Already, the multicentric European project ADHOC, the AgeD in HOme Care (7th Framework Program of the European Commission, 2001–2005) in one of its ancillary studies con- firmed that the percentage of approved PIMs stated by combined lists of Beers 1997 and 2003 criteria and McLeod’s 1997 criteria ranged from 31.6% in Norway to 70.9% in Italy. In the majority of European countries, approval rates of PIMs were around 50% (e.g. 48.1% in the Netherlands, 50.6%

in Iceland, 51.9% in Denmark and Czech Republic (CZ), and 55.7% in Finland and United Kingdom), but these PIM lists and the prevalence of prescrib- ing of individual PIMs widely differed. For exam- ple, pentoxifylline was overprescribed to 20% of older adults in the CZ (and broadly advertised) while in other EU countries, this PIM was not approved for clinical use (e.g. in Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom) or was used rarely (prevalence of 1.1% in Finland and 1.2% in Italy).24 Similar discrepancies have also been found for many other PIMs. These findings raised attention to regulatory issues related to PIM use in our research.

In the European Union, protection of public health and the high quality, effective and safe medicinal products should be guaranteed by the European regulatory system for medicines within the EU. This system is represented by the net- work of medicines’ regulatory authorities from 31 European Economic Area member states, the European Commission and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).25 All medicines in the EU must be authorized before being available for patients and there are different routes for author- izing medicinal products. The centralized author- ization procedure is laid down by the regulation (EC) no. 726/20042 of the European Parliament and of the Council. For this type of authorization

there is a single application, a single evaluation by the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) or Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use (CVMP) and consecutively, the authorization is granted by the European Commission.26 Such marketing authorization is valid for entire EU market and all member states.27 Some specific medicines (e.g.

most innovative medicines) fall into the scope of mandatory centralized authorization procedure.25 However, there are also other types of authoriza- tion procedures, mainly the decentralized proce- dure, mutual-recognition and national author- ization procedure. The decentralized procedure can be used in situation when a medicinal prod- uct is not authorized in any of the EU countries yet and the company applies for the authorization in more than one EU member state at the same time. The mutual-recognition procedure is repre- sented by the situation when a medicinal product is authorized in only one EU member state and the company applies for authorization in other EU countries (this type of procedure allows EU member states to rely on each other’s scientific assessments) and the national procedure repre- sents the authorization procedure unique to every EU member state.25–27

Most of the medicines available in the EU (and particularly, older medicines like PIMs mostly are) were authorized for clinical use at the national level. They were mostly authorized before EMA’s creation and were not in the scope of the centralized authorization procedure. For this reason, approval rates, recommendations and preferences for the use of PIMs highly differ in different EU countries. Different approval rates of PIMs and regulations [e.g. prescribing limits for individual PIMs, over-the-counter (OTC) availability, etc.] also significantly influ- ence the applicability of different PIM criteria in research and clinical practice.24,28

Because the EU(7)-PIM list becomes one of the preferred tools for clinical practice and research in European studies, the aim of our study was to describe (using quantitative and qualitative analy- ses) the approval rates and selected regulatory aspects (e.g. EMA’s authorization, actual availa- bility on the pharmaceutical market, and availabil- ity only on prescription or as an OTC medication) for PIMs stated on the EU(7)-PIM list in com- parison with PIMs stated by the AGS Beers crite- ria in several EU countries [Czech Republic (CZ),

Hungary (HU), Republic of Serbia (RS), Spain (ES), Portugal (PT), and Turkey (TR)], partici- pating in the EU COST Action IS1402 WG1b research initiative.29 The aim of our analyses was to obtain first evidence for the newly starting FIP7 EUROAGEISM Horizont 2020 project that will focus on documenting clinical conditions of PIM use, country-specific prescribing habits and regu- latory measures related to PIM prescribing in dif- ferent EU countries, including mainly Central and Eastern European countries.30

Methodology Research team

Research teams of six European countries (CZ, ES, PT, RS, HU, and TR) involved in the WG1b working subgroup ‘Healthy clinical strategies for healthy aging’ of the EU COST Action IS1402 ini- tiative (2015–2018)29 participated in this research study. Selection of countries was not intentional;

all countries participating in the WG1b EU COST Action IS1402 group were invited, and finally the six above-stated EU countries joined this research held in the period 2015–2018.

Design and methodology of our research was set up at two initial EU COST Action IS1402 face- to-face meetings in Dublin, Ireland (October 2015) and Prague, CZ (April 2016). Discussions on data collection and corrections, as well as on analyses and results interpretation were con- ducted during other face-to-face scientific meet- ings, organized twice a year by the EU COST Action WG1b group in the period between December 2015 and October 2018, under finan- cial support of the EU COST Action IS1402.

Explicit criteria of PIMs

The list of PIMs used in our research was created from two explicit criteria of PIMs in the older population published in the USA and Europe in 2015. These were the AGS 2015 Beers criteria (Section 1),4 which represented the latest Beers criteria update at the time of our study (in January 2019, a new update of AGS Beers 2019 was released).5 These criteria were developed by experts of the AGS. Also, the EU(7)-PIM list published by Renom-Guiteras and colleagues7 was used in our analyses as the first international European tool developed for international stud- ies. Both of these criteria [EU(7)-PIM and AGS

Beers criteria] represent the most known and most comprehensive tools in the US and Europe today, applicable in regulatory studies. Because the STOPP/START criteria require for identifi- cation of PIMs the data on clinical conditions of medication use in an individual patient (lab val- ues and results of other clinical assessments), they were not applicable in our research.6 The AGS 2015 Beers criteria (Section 1) and EU(7)-PIM list were mostly used because potential inappro- priateness of PIMs according to these criteria was defined mostly by medication-related character- istics (e.g. limits of a single dose, retard and nonretard drug forms, route of application, etc.).

The 2015 AGS Beers criteria consisted of four sections and of those only Section 1 (PIMs mostly independent on clinical conditions) was selected for our research.4 The EU(7)-PIM criteria stated mostly PIMs independent of diagnoses and other clinical conditions (with a few exceptions)6 and all items were included in analyses [e.g. dis- regarding the length of the treatment and several disease-related conditions for a few PIMs (on both lists) to use as extensive methodology as possible].

Focus of our analyses was mainly on approval rates of PIMs (with regard to or not including specific medication-related conditions of inappropriateness;

and on actually marketed PIMs (see Figure 1 in the Results section), and their availability on prescription or also as OTC drugs (see Figure 3 in Results section). With regard to medication- related conditions of inappropriateness, we con- ducted evaluation of all approved brand names, drug forms and doses in individual countries.

However, our intention was not to focus on com- parisons of all relative contraindications, specific warnings for the geriatric population, and clinical conditions defining appropriate/inappropriate use of PIMs in the summary product characteristics (SPCs) because such study would require a huge effort of international expert teams and merits more extensive and specifically developed meth- odology. Considering the huge number of brand names of PIMs approved by national authoriza- tion procedures in different countries (different drug forms, doses, etc.), even our analyses com- paring approval rates of PIMs, their marketing, and availability only on prescription or as OTC drugs required substantial effort and is excep- tional in the scientific literature. We also studied qualitative differences in approval rates of PIMs,

means differences in PIMs withdrawn from the pharmaceutical markets by regulatory agencies between 2016 and 2018, and newly approved for clinical use in this period. We also searched which PIMs from the total list were approved by the central authorization procedure of the EMA.

Primary data for our study were collected between September and December 2016 and checked and corrected during spring 2017.

Problematic areas were discussed during face-to- face meetings in the period 2016–2018, and last check and corrections of data were conducted in autumn 2018 (before first submission of our research paper) and during the first revisions in February–March 2019. Information was obtained from official websites of national drug-regulatory institutes31–43 and verified by national research teams using national drug compendia, national drug formularies, reimbursement compendia, or using opinions of experts from national regula- tory institutes. Country-specific research teams recorded all necessary information (see Table 1) and this was checked twice by two independent researchers.31–51

Data summary and statistical analyses

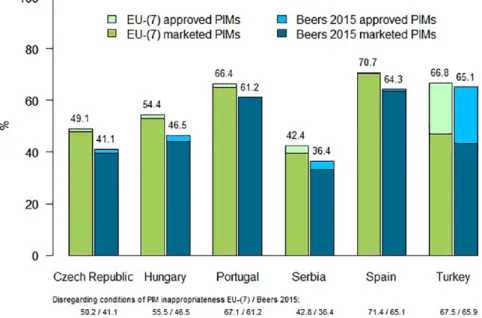

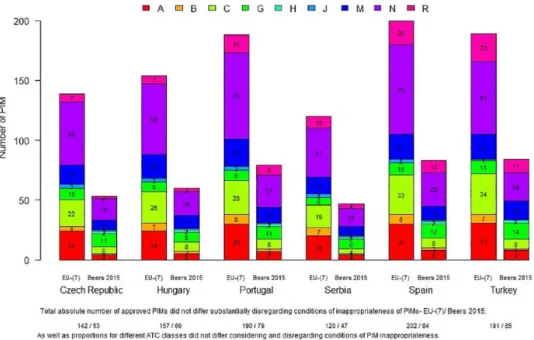

We used descriptive statistical methods to express quantitative differences in approval rates of PIMs in participating countries for 2018 year. Results of quantitative analyses were summarized in graphs presenting differences in approval rates of PIMs in participating EU countries using EU(7)-PIM list and 2015 AGS Beers criteria (comparing approved and currently marketed PIMs, as well as results obtained regarding or not including conditions of inappropriateness of PIMs; see Figure 1). Also another graph has been created to document absolute numbers of PIMs approved for clinical use in individual countries using EU(7)-PIM list and AGS 2015 Beers criteria based on the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (again, both regarding and not including condi- tions of PIM inappropriateness, see Figure 2). We also documented percentages of marketed PIMs available only on prescription or as OTC medica- tions (see Figure 3).

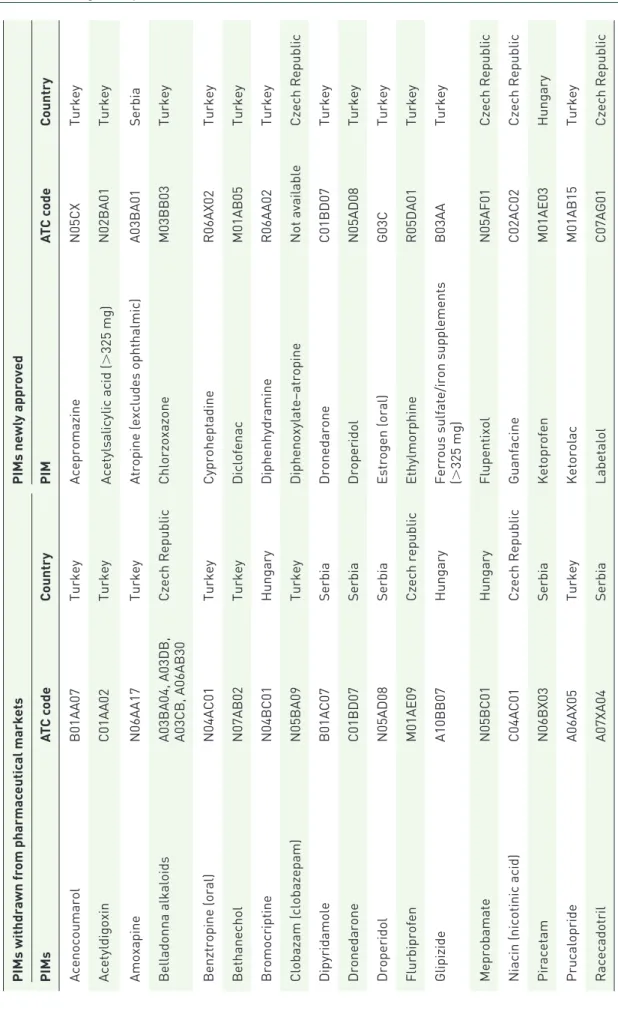

In the summary tables, we described changes in PIMs approved for clinical use on different phar- maceutical markets between 2016 and 2018 (see Table 3, newly approved PIMs and PIMs

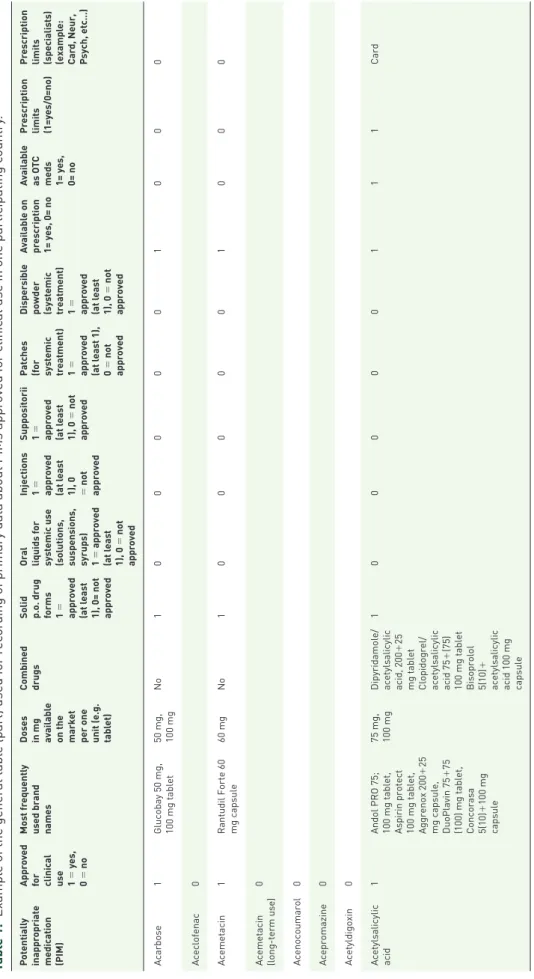

Table 1. Example of the general table (part) used for recording of primary data about PIMs approved for clinical use in one participating country. Potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) Approved for clinical use 1 = yes, 0 = no Most frequently used brand names

Doses in mg available on the market per one unit (e.g. tablet) Combined drugsSolid p.o. drug forms 1 = approved (at least 1), 0= not approved Oral liquids for systemic use (solutions, suspensions, syrups) 1 = approved (at least 1), 0 = not approved Injections 1 = approved (at least 1), 0 = not approved Suppositorii 1 = approved (at least 1), 0 = not approved Patches (for systemic treatment) 1 = approved (at least 1), 0 = not approved Dispersible powder (systemic treatment) 1 = approved (at least 1), 0 = not approved Available on prescription 1= yes, 0= no

Available as OTC meds 1= yes, 0= no Prescription limits (1=yes/0=no)

Prescription limits (specialists) (example: Card, Neur, Psych, etc…) Acarbose1Glucobay 50 mg, 100 mg tablet50 mg, 100 mgNo1000001000 Aceclofenac0 Acemetacin1Rantudil Forte 60 mg capsule60 mgNo1000001000 Acemetacin (long-term use)0 Acenocoumarol0 Acepromazine0 Acetyldigoxin0 Acetylsalicylic acid1Andol PRO 75; 100 mg tablet, Aspirin protect 100 mg tablet, Aggrenox 200+25 mg capsule, DuoPlavin 75+75 (100) mg tablet, Concorasa 5(10)+100 mg capsule

75 mg, 100 mgDipyridamole/ acetylsalicylic acid, 200+25 mg tablet Clopidogrel/ acetylsalicylic acid 75+(75) 100 mg tablet Bisoprolol 5(10)+ acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg capsule

100000111Card

Figure 1. Percentages of approved and marketed PIMs by EU(7)-PIM list and AGS Beers 2015 criteria in six EU countries (regarding the conditions of inappropriateness of PIMs).

AGS, American Geriatric Society; ATC, Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

withdrawn from the pharmaceutical market in individual countries) and characteristics of PIMs approved for clinical use in only one of six ana- lyzed countries (see Table 4). Also, percentages of PIMs approved by the central authorization procedure of the EMA have been expressed and stated in the text in the Discussion section.

All charts were made using R software (version 3.5.1). The differences in the proportion of PIMs approved for clinical use on pharmaceutical mar- kets according to the EU(7)-PIM list and 2015 AGS Beers criteria were stated using percentages.

Differences in results over 5% were considered substantial.

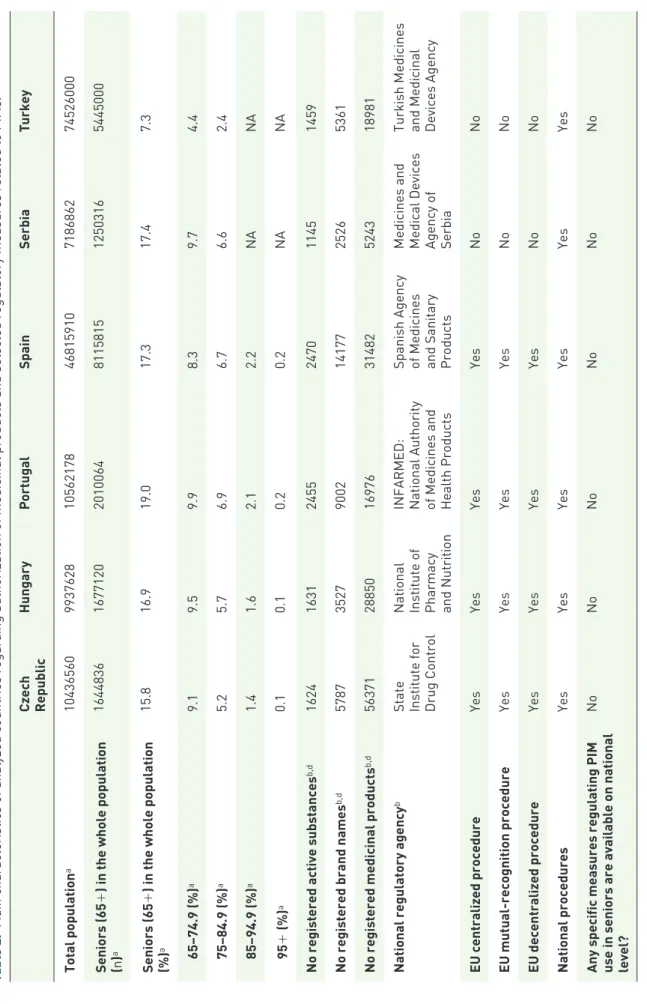

In order to describe and appropriately comment on main differences between regulatory systems in different countries, we created Table 2 that describes the total number of inhabitants, pro- portion and absolute number of seniors in the population in individual countries, number of approved medicinal products, brand names and active substances, types of medicine authorization procedures and responsible national institutions, as well as selected information on specific educa- tional programs or guidelines helping to increase

knowledge about PIMs and regulate PIM use at a national level (see references31–51).

Results

Table 2 shows the differences in main character- istics among participating countries: the size of total and senior population, medicines marketing authorization procedures, national responsible institutions, and availability of medication safety and educational strategies or guidelines related to PIMs in individual countries. In relation to the areas described in Table 2, major differences were found in the size of total population (the largest country was TR with over 74 million inhabitants, and the second largest, ES, with more than 46 million inhabitants), in the pro- portion of older adults in the population (7.3%

in TR compared with 15.8–19.0% in other countries), and in lower numbers of registered active substances in TR and RS (see Table 2).

Comparing the medication authorization proce- dures, the EU countries (ES, PT, CZ and HU) respected the central authorization procedures of the EMA; however, in EU-candidate countries (TR and RS) only national medication authori- zation procedures were applied. No substantial

Figure 2. Absolute numbers of PIMs approved for clinical use according to EU(7)-PIM list and AGS Beers 2015 criteria (regarding medication-related conditions of PIMs’ inappropriateness, by ATC classification).

A (red)- PIMs used for the treatment of “ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM, B (orange)- PIMs used for the treatment of “BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS”, C (yellow)- “CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM” PIMs, G (green)- “GENITO URINARY SYSTEM AND SEX HORMONES” PIMs, H (light blue)- PIMs from “SYSTEMIC HORMONAL PREPARATIONS, EXCL.

SEX HORMONES AND INSULINS”, J (middle blue)- PIMs from “ANTIINFECTIVES FOR SYSTEMIC USE”, M (dark blue)-

“MUSCULO-SKELETAL SYSTEM” PIMs, N (purple)- “NERVOUS SYSTEM” PIMs and R (pink)- “RESPIRATORY SYSTEM” PIMs, AGS American Geriatric Society; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Figure 3. Percentages of marketed PIMs available on prescription only or as OTC medicines in six EU countries (with regard to the conditions of PIM inappropriateness).

Prevalence of marketed PIMs also available as OTC medications did not differ substantially with regard to or not including conditions of PIM inappropriateness.

EU, European Union; OTC, over the counter; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Table 2. Main characteristics of analyzed countries regarding authorization of medicinal products and selected regulatory measures related to PIMs.31–51

Czech Republic

HungaryPortugalSpainSerbiaTurkey Total populationa1043656099376281056217846815910718686274526000 Seniors (65+) in the whole population (n)a164483616771202010064811581512503165445000 Seniors (65+) in the whole population (%)a15.816.919.017.317.47.3 65–74.9 (%)a9.19.59.98.39.74.4 75–84.9 (%)a5.25.76.96.76.62.4 85–94.9 (%)a1.41.62.12.2NANA 95+ (%)a0.10.10.20.2NANA No registered active substancesb,d162416312455247011451459 No registered brand namesb,d5787352790021417725265361 No registered medicinal productsb,d56371288501697631482524318981 National regulatory agencyb

State Institute for Drug Control National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition INFARMED: National Authority of Medicines and Health Products Spanish Agency of Medicines and Sanitary Products Medicines and Medical Devices Agency of Serbia Turkish Medicines and Medicinal Devices Agency

EU centralized procedureYesYesYesYesNoNo EU mutual-recognition procedureYesYesYesYesNoNo EU decentralized procedureYesYesYesYesNoNo National proceduresYesYesYesYesYesYes

Any specific measures regulating PIM use in seniors are available on national level?

NoNoNoNoNoNo

Czech Republic

HungaryPortugalSpainSerbiaTurkey

Any specific measures regarding medication safety in seniors are available on national level (except regular (and mostly general) warnings in medication Summary product characteristics and patient leaflets)?

NoNoNoNoNoNo

If there is any country-specific clinical guideline/recommendation regarding PIM use in older patients available?

c

YesNoNoYesNoYes

Education course/courses on PIMs included regularly in pregraduate education of pharmacists No*No*No*No*No*No*

Education course/courses on PIMs included regularly in pregraduate education of physicians

No*No*No*No*No*No*

Education course/courses on PIMs (efficacy, safety in older patients) included in postgraduate education of pharmacists/clinical pharmacists No**No**No**No**No**No**

Education course/courses on PIMs (efficacy, safety in older patients) regularly included in postgraduate education of general practicioners or other physicians No, regular courses are organized only for geriatricians (twice a year)

No**No**No**No**No** *Some faculties may have a separate lecture on this topics, but there are no obligatory subjects, courses, or modules taught as part of regular curricula. **No specific courses; only general separate lectures in postgraduate continuing education courses are organized. a2011 census data sources: (a) for EU countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Portugal and Spain): European Statistical System;44 (b) for Serbia: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia;45 (c) for Turkey: the Turkish Statistical Institute.46 bFor the majority of countries, excluding homeopathic products and radiopharmaceuticals, except Serbia, where all approved medicinal products are stated for all rows. Sources: (a) for the Czech Republic;42 (b) for Hungary;40 (c) for Portugal;35 (d) for Spain;41 (e) for Serbia;36 (f) for Turkey.43 cSources: (a) for the Czech Republic;47 (b) for Spain;48,49 (c) for Turkey.50,51 dLatest data for the majority of countries were available for 2017, except Portugal (2018) and Spain (2019). Radiopharmaceuticals, herbal, and homeopathic medicinal products were excluded from calculations (except Serbia where all medicinal products were included). EU, European Union; NA, not available; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Table 2. (Continued)

Table 3. PIMs withdrawn or newly approved on pharmaceutical markets of participating countries between years 2016 and 2018. PIMs withdrawn from pharmaceutical marketsPIMs newly approved PIMsATC codeCountryPIMATC codeCountry AcenocoumarolB01AA07TurkeyAcepromazineN05CXTurkey AcetyldigoxinC01AA02TurkeyAcetylsalicylic acid (>325 mg)N02BA01Turkey AmoxapineN06AA17TurkeyAtropine (excludes ophthalmic)A03BA01Serbia Belladonna alkaloids A03BA04, A03DB, A03CB, A06AB30

Czech RepublicChlorzoxazoneM03BB03Turkey Benztropine (oral)N04AC01TurkeyCyproheptadineR06AX02Turkey BethanecholN07AB02TurkeyDiclofenacM01AB05Turkey BromocriptineN04BC01HungaryDiphenhydramineR06AA02Turkey Clobazam (clobazepam)N05BA09TurkeyDiphenoxylate–atropineNot availableCzech Republic DipyridamoleB01AC07SerbiaDronedaroneC01BD07Turkey DronedaroneC01BD07SerbiaDroperidolN05AD08Turkey DroperidolN05AD08SerbiaEstrogen (oral)G03CTurkey FlurbiprofenM01AE09Czech republicEthylmorphineR05DA01Turkey GlipizideA10BB07Hungary

Ferrous sulfate/iron supplements (B03AATurkey >325 mg) MeprobamateN05BC01HungaryFlupentixolN05AF01Czech Republic Niacin (nicotinic acid)C04AC01Czech RepublicGuanfacineC02AC02Czech Republic PiracetamN06BX03SerbiaKetoprofenM01AE03Hungary PrucaloprideA06AX05TurkeyKetorolacM01AB15Turkey RacecadotrilA07XA04SerbiaLabetalolC07AG01Czech Republic

PIMs withdrawn from pharmaceutical marketsPIMs newly approved PIMsATC codeCountryPIMATC codeCountry SelegilineN04BD01TurkeyMethyldopaC02AB02Turkey Strontium ranelateM05BX03SerbiaNifedipine (sustained release)C08CA05Turkey TolterodineG04BD07HungaryNitrofurantoinJ01XE01Serbia, Turkey Tolterodine (nonsustained release)G04BD07HungaryOfloxacinJ01MA01Turkey Tolterodine (sustained release)G04BD07PortugalOxaprozin (oral)M01AE12Turkey TranylcypromineN06AF04SpainOxazepamN05BA04Serbia VincamineC04AX07PortugalOxybutynine (nonsustained release)G04BD04Turkey ZaleplonN05CF03SerbiaOxybutynine (sustained release)G04BD04Czech Republic Zaleplon (>5 mg)N05CF03SerbiaPrasugrelB01AC22Serbia Zopiclone (>3.75 mg)N05CF01SerbiaQuinine and derivativesM09AATurkey ZuclopenthixolN05AF05SerbiaTolterodine (sustained release)G04BD07Czech Republic TrihexyphenidylN04AA01Turkey Zopiclone (>3.75 mg)N05CF01Portugal Zopiclone (>3.75 mg)N05CF01Turkey ATC, Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Table 3. (Continued)

differences have been found in availability of spe- cific regulatory measures related to PIM use or in educational strategies in this area. There were mostly unavailable specific guidelines, educa- tional courses and regulatory measures related to PIMs as a specific group of risky medications in older patients in the majority of countries (the exceptional positive cases were only a few educa- tional strategies, not regularly and systematically promoted or implemented at the national level in individual countries).

In quantitative analyses of approval rates of PIMs in individual countries (with regard to medication- related conditions of inappropriateness), three countries reached higher prevalence by EU(7)- PIM/AGS Beers 2015 criteria. These were ES (70.7%/64.3%), TR (66.8%/65.1%), and PT (66.4%/61.2%). In the other three countries, per- centages of PIMs approved on pharmaceutical markets fluctuated at around 50% or less, namely in HU 54.4%/46.5%, CZ 49.1%/41.1%, and RS 42.4%/36.4%. There were substantial differences (>5%) in the proportion of PIMs approved on pharmaceutical markets in all countries according to the EU(7)-PIM list compared with AGS Beers 2015 criteria except in TR, where this difference did not exceed 1.7% (see Figure 1). Apart from conditions of PIM inappropriateness, results yielded nearly the same prevalence (difference was maximally 1.1% for all outputs, see Figure 1).

Differences between approved PIMs for clinical use and currently marketed PIMs on the pharma- ceutical market were not substantial in nearly all countries except TR. For this country, difference reached 19.8% for the EU(7)-PIM list and 21.7%

for the AGS Beers 2015 criteria.

Similar findings have also been obtained for abso- lute numbers of PIMs approved for clinical use in different countries according to the ATC classifi- cation [using EU(7)-PIM criteria and AGS Beers 2015 criteria] when conditions of inappropriate- ness were considered or disregarded (see Figure 2).

These absolute numbers for EU(7) criteria (regard- ing conditions of PIM inappropriateness) ranged from 120 in RS to 200 in ES, and for AGS Beers 2015 criteria, from 47 in RS to 83/84 in ES/TR. The absolute numbers of approved PIMs were substantially higher for PIMs stated on the EU(7)-PIM list in all countries when compared

with AGS Beers 2015 criteria regarding conditions of PIM inappropriateness (+86 in CZ, +94 in HU, +109 in PT, +73 PIMs in RS, +117 in ES, and +105 in TR). According to the ATC classifi- cation and EU(7)-PIM list, these absolute num- bers of PIMs approved for clinical use were found highest for ATC classes N (central nervous system PIMs; in different countries they ranged n = 41–75) and then fro ATC class C (cardiovascular PIMs, n = 19–34), A (alimentary tract PIMs, n = 21–32), M (musculoskeletal PIMs, n = 14–23) and R (res- piratory tract PIMs, n = 7–23). Results not includ- ing conditions of PIM inappropriateness yielded nearly the same findings.

Considering the majority of European coun- tries, the availability of marketed PIMs as OTC medications (including conditions of PIM inap- propriateness) ranged always below the preva- lence of 20% for both explicit criteria (from 9.8% in CZ to 17.9% in RS). The exception was TR, where availability of marketed PIMs as OTC medications reached 46.4–48.1%.

In qualitative longitudinal analyses, only 26/29 PIMs (not including/with regard to the conditions of PIM’s inappropriateness) have been withdrawn from pharmaceutical markets and 30/32 PIMs newly approved for clinical use in pharmaceutical markets of analyzed countries between 2016–

2018. In CZ (n = 6) and TR (n = 21), the highest absolute number of PIMs were approved for clin- ical use in this period, while in other countries, this number was lower (<4). The highest abso- lute number of PIMs were withdrawn from phar- maceutical markets in RS (n = 10), TR (n = 8), and HU (n = 5; in other countries these were only a few PIMs, <3; see Table 3).

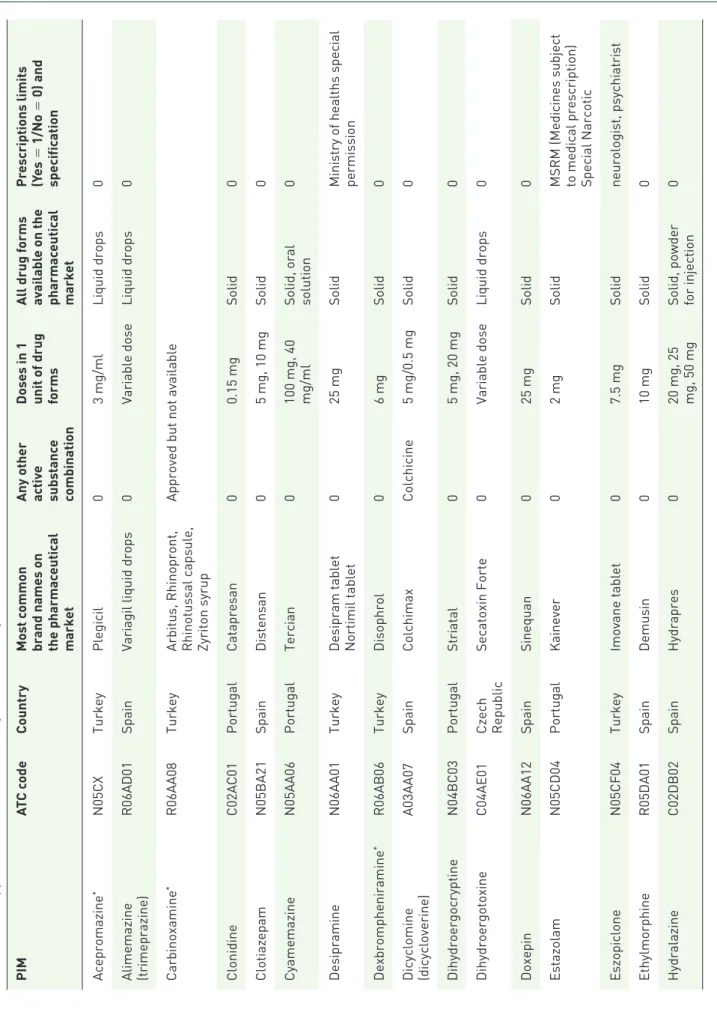

Qualitative analyses discovered some PIMs that have been approved in only one of six analyzed EU countries and may be considered ‘unneces- sary’ (see Table 4). The majority of these PIMs have been approved for clinical use in TR (n = 14), but some of these PIMs (n = 8) have not been marketed for a long time (see Table 4). More PIMs have been also specifically available on pharma- ceutical markets in ES (n = 12), and PT (n = 6).

In CZ and HU, there was only one PIM each (dihydroergotoxine and zaleplon, respectively).

For more information, refer to Table 4.

Table 4. PIMs approved for clinical use in only one of six analyzed countries. PIMATC codeCountryMost common brand names on the pharmaceutical market Any other activ

e substance combination

Doses in 1 unit of drug forms

All drug forms available on the pharmaceutical market

Prescriptions limits (Yes = 1/No = 0) and specification Acepromazine*N05CXTurkeyPlegicil03 mg/mlLiquid drops0

Alimemazine (trimeprazine)

R06AD01SpainVariagil liquid drops0Variable doseLiquid drops0 Carbinoxamine*R06AA08Turkey

Arbitus, Rhinopront, Rhinotussal capsule, Zyriton syrup

Approved but not available ClonidineC02AC01PortugalCatapresan00.15 mgSolid0 ClotiazepamN05BA21SpainDistensan05 mg, 10 mgSolid0 CyamemazineN05AA06PortugalTercian0

100 mg, 40 mg/ml Solid, oral solution

0 DesipramineN06AA01Turkey

Desipram tablet Nortimil tablet

025 mgSolid

Ministry of healths special permission

Dexbrompheniramine*R06AB06TurkeyDisophrol06 mgSolid0 Dicyclomine (dicycloverine)

A03AA07SpainColchimaxColchicine5 mg/0.5 mgSolid0 DihydroergocryptineN04BC03PortugalStriatal05 mg, 20 mgSolid0 DihydroergotoxineC04AE01

Czech Republic

Secatoxin Forte0Variable doseLiquid drops0 DoxepinN06AA12SpainSinequan025 mgSolid0 EstazolamN05CD04PortugalKainever02 mgSolid

MSRM (Medicines subject to medical prescription) Special Narcotic

EszopicloneN05CF04TurkeyImovane tablet07.5 mgSolidneurologist, psychiatrist EthylmorphineR05DA01SpainDemusin010 mgSolid0 HydralazineC02DB02SpainHydrapres0

20 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg Solid, powder for injection

0 (Continued)

PIMATC codeCountryMost common brand names on the pharmaceutical market Any other activ

e substance combination

Doses in 1 unit of drug forms

All drug forms available on the pharmaceutical market

Prescriptions limits (Yes = 1/No = 0) and specification LoflazepateN05BA18PortugalVictan12 mgSolid0 LormetazepamN05CD04Spain

Aldosomnil, Loramet, Lormetazepam Sandoz, Noctamid

0

1 mg, 2 mg, 0.2 mg/ml, 2.5 mg/ml Solid, injection, oral drops

0 Meprobamate*N05BC01TurkeyDanitrin0200 mgSolid0 MethyltestosteroneG03BA02TurkeyAfro025 mgSolid0 Oxaprozin (oral)*M01AE12TurkeyDuraprox0600 mgSolid0 PerphenazineN05AB03SpainDecentan08 mgSolid0 PindololC07AA03TurkeyVisken tablet05 mgSolid,0 ProcainamideC01BA02SpainBiocoryl01000 mgInjection0

Propericiazine (periciazine)

N05AC01SpainNemactil0

10 mg, 50 mg, 40 mg/ ml

Solid, oral drops0 QuazepamN05CD10SpainQuiedorm015 mgSolid0 ReserpineC02AA02TurkeyRegroton00.25 mgSolid0 Terfenadine*R06AX12TurkeySanofen060 mgSolid0 Thioridazine*N05AC02TurkeyApproved but not available Tolmetin (oral)*M01AB0TurkeyTolectin0200 mgSolid0 TrifluoperazineN05AB06TurkeyStilizan02 mgSolid0 VinburnineC04AX17PortugalCervoxan040 mgSolid0 VincamineC04AX07SpainAnacervixPiracetam

400 mg/20 mg

Solid0 ZaleplonN05CF03HungaryAndante05 mgSolid0 *Approved for clinical use but has not been marketed for a long time.

Table 4. (Continued)

Discussion

Our study is the first study analyzing in detail cross- country differences in approval rates of PIMs, their actual marketing and availability on prescription or as OTC medications. We also analyzed longitudi- nal changes in PIM approval rates between 2016 and 2018 (withdrawals from the pharmaceutical markets and new approvals) in six European coun- tries, taking part in the scientific works of the EU COST Action IS1402 WG1b research group.

These were ES and PT (long-term member states of the EU), CZ and HU (short-term EU member states), and TR and RS (EU-candidate countries).

The aim of our research was to analyze qualitative and quantitative differences in the lists of PIMs approved for clinical use and marketed in these countries, to describe selected differences in regula- tory aspects related to PIM approvals, marketing and availability that should be harmonized and bet- ter regulated in future decades.

We chose for our analyses two latest EU- and US-explicit criteria of PIMs, namely the EU(7)- PIM list (European tool representing the most comprehensive explicit list of PIMs developed for international European research)7 and the AGS 2015 Beers criteria (at the time of our analyses, the latest and the most comprehensive tool in the US from which only the Section 1 was applicable in our regulatory analyses).4 Results of our analyses confirmed that PIMs stated on the EU(7)-PIM list were approved for clinical use in participating EU countries more often than PIMs stated in AGS 2015 Beers criteria (approval rates ranged for EU(7)-PIM list from 42.4% in RS to 70.7% in ES and for AGS Beers 2015 Criteria from 36.4% in RS to 64.3% in ES, respectively, with regard to the conditions of PIM inappropriateness). Only in TR, differences between the two analyzed criteria were not substantial, which means lower than 5%.

In agreement with our findings, several epidemio- logical studies in Europe confirmed that PIM prev- alence with the EU(7)-PIM list was higher than after application of 2015 AGS Beers criteria. For example, the German study in community-dwell- ing older patients identified 37.4% PIM users after application of the EU(7)-PIM list and only 26.4%

according to AGS Beers 2015 criteria, with longi- tudinal decrease in 6 years to 36.5% and 23.1%, respectively.52 In Lithuania, the study of Grina and colleagues analyzed medication claim data in older outpatients and confirmed that application of the EU(7)-PIM list documented the prevalence of 57.2%, while by the application of the AGS Beers

2015 criteria the prevalence was only 25.9%.53 Also in TR (a European–Asian country), the prevalence of PIM use was found to be 30% after application of the AGS Beers 2015 criteria in com- munity-dwelling older patients,54 and 65% when the EU(7)-PIM list was applied in the outpatient setting.55 Even if both the EU(7)-PIM list and AGS Beers 2015 criteria have been developed for international research purposes, the EU(7)-PIM list identifies higher PIM prevalence in European countries. However, results of PIM prevalence can be of course influenced by many other factors, for example, preferences in PIM use, regulatory meas- ures, etc.

Moreover, the AGS Beers 2015 criteria include more PIMs defined by clinical conditions of inap- propriateness;51,52 for instance, the comparison of the AGS Beers 2015 criteria and STOPP version 2 criteria in the clinical setting in one Spanish study yielded nearly the same and very high prev- alence, almost 70%,56 which confirms that these tools may also be highly applicable in clinical studies in EU countries. Also, our results were influenced by the fact (see Figure 2) that a signifi- cantly lower number of PIMs was stated in Section 1 of the AGS Beers 2015 criteria in com- parison with the EU(7)-PIM list.

Considering the countries participating in our research, the highest approval rates of PIMs were demonstrated in ES (70.7% of PIMs regarding medication-related conditions of inappropriate- ness and 71.4% not including conditions of PIM inappropriateness). This is in agreement with the fact that ES was the only country involved in the development of the EU(7)-PIM list7 and we discovered during our analyses that many specific PIMs from the EU(7)-PIM list were approved only on the Spanish pharmaceutical market. Higher prevalence of approved PIMs was also documented in PT and TR (according to the EU(7)-PIM list, 67.1% and 67.5%, respectively, not including conditions of inappropriateness).

While similar results in PT and ES can be explained by similarities between Spanish and Portuguese pharmaceutical markets, in TR, these findings are most likely more influenced by different drug- regulatory measures.57

TR and RS are not EU member states, only EU-candidate countries; therefore, granting marketing authorization to medical products through the centralized authorization procedure

of the EMA or other EU authorization proce- dures (see Table 2 and the Introduction) are not applied. Even if licensing processes in both of the countries are now harmonized with EU legislation, national authorization procedures still dominate.57 Table 2 shows that national authorization proce- dures in these countries contribute to lower avail- ability of active substances, and in the case of RS, also to lower availability of PIMs. This is fairly different in TR, where the prevalence of approved PIMs was high, and also the total number of registered medicinal products was the highest (see Table 2), as well as the variability of different approved brand names, strengths, and drug forms of PIMs. According to the article of Oner and col- leagues, the EMA, US Food and Drug Agency and Turkish Medicines and Medicinal Devices Agency apply different regulatory measures and different authorization procedures, and are autonomous in their decisions.57 Many PIMs listed in Table 3 are approved only on the Turkish pharmaceutical market, not in other EU coun- tries. However, some of these PIMs are not mar- keted anymore (e.g. acepromazine, belladonna alkaloids, buclizine, carbinoxamine, chlordiaze- poxide, etc.) This could also mean that TR as an EU-candidate country (the opposite of RS) still does not fully apply the rule of EU legislation called the ‘sunset clause,’ a legal provision stating that the marketing authorization of a medicine will cease to be valid if the medicine is not placed on the market within 3 years of the authorization being granted or if the medicine is removed from the market for 3 consecutive years.25–27 In agree- ment with these findings, TR was the country in our sample with the highest discrepancies between approved and actually marketed PIMs (the differ- ence was 19.8% for the EU(7)-PIM list and 21.7% for AGS Beers 2015 criteria), in other countries, these differences were not substantial.

Also, the highest number of PIMs without pre- scription was available in TR [over 45% using EU(7) or AGS Beers 2015 criteria, compared with less than 18% in other EU countries]. On the other hand, in RS, EU rules were followed more closely and according to local experts from the Medicines and Medicinal Devices Agency of RS, lower numbers of registered medicinal prod- ucts in this country also highly contributed to the generally lower number of approved PIMs.

In Central and Eastern EU countries (CZ, HU and RS), specificity of the EU(7)-PIM list to local phar- maceutical market and approved PIMs was much

lower than in ES, PT and TR [according to the EU(7)-PIM list, 50.2% PIMs were approved for clinical use in CZ, 55.5% in HU and 42.8% in RS, not including conditions of inappropriateness of PIMs]. In a recently published study in Lithuania, 127 out of 282 from EU(7)-PIMs (45%) and 58 out of 136 of PIMs reported from the 2015 AGS Beers criteria (43%) were available on the Lithuanian pharmaceutical market.53 In a Croatian study, 125 out of 335 EU(7)-PIMs (37.3%)58 and in a Belgium study, 178 out of 335 (53.1%) were approved.28 These studies are in agreement with our findings.

Our results might show that more comprehensive criteria for EU research are needed. However, it is important to emphasize that the EU(7)-PIM list currently contains many frequently prescribed medications (e.g. zolpidem > 5 mg, zopiclone >

3.75 mg, omeprazole in long-term use, etc.), and for this reason, sensitivity of these criteria is still very high in the majority of EU countries and these criteria enable detection of high prevalence of PIM prescribing also in Central and Eastern Europe.

For example, the prevalence obtained with EU(7) criteria was 57.2% in Lithuanian community-residing older patients,53 and 66.7% in a Croatian study assessing prescribing of PIMs in older adults dis- charged from acute care.58

Particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, where many countries except Estonia did not participate in development of the EU(7)-PIM list, ‘other new’

PIMs may be available, not yet defined by the EU(7) and AGS Beers 2015 criteria. These are, for example, tofisopam (N05BA23), cinolazepam (N05CD13), mirabegron (G04BD12), propiverin hydrochloride (G04BD06), etc.46 Such PIMs should be first identified through efforts of national expert panels in different countries, and later sum- marized again in an international European tool.

Moreover, our longitudinal analyses confirmed that PIMs are still newly approved on pharmaceu- tical markets of EU countries and mostly by national authorization procedures. The majority of PIMs evaluated in our research have been author- ized by national authorization procedures (95%), while only 5% were approved by the central authorization procedure of the EMA.

According to our findings, some PIMs have been approved in only one out of the six analyzed EU countries. The majority of these specific PIMs have been identified, particularly in PT, ES and TR. These qualitative discrepancies in approval rates of PIMs should be thoroughly studied by