The data used for this article is a subset of the dataset collected by the WDN survey. In particular, the degree of price and wage rigidity determines the speed of adjustment of the economy and the level of the associated costs.

HOW OFTEN ARE PRicES AND WAGES ADJuSTED?

Another important and robust result of these studies was the substantial heterogeneity of the frequency of price changes between products and sectors, which appears to be related, among other things, to the variability in the cost structure at firm and sectoral level, especially in the relative importance of labor costs.5. The information on price and wage adjustments collected by the WDN survey contributes to filling the gap related to the lack of data on wage policies at the firm level and at the same time addressing the issue of the degree of price adjustment and wage stability.

THE TiMiNG OF ADJuSTMENT

To account for the fact that individual firms do not continuously change their prices and wages in response to all the relevant shocks that hit them, firms' strategies in the literature are modeled either as a time-dependent process, where the timing of adjustment is exogenously given and does not depend of the state of the economy, or as a state-dependent such. In order to obtain more empirical evidence on these questions, firms in the WDN survey were asked to specify whether their wage and price changes take place without a predefined pattern or are concentrated in certain month(s) (see Appendix 2, questions 10 and 32). In fact, the proportion of companies that typically change wages in certain months is 54 percent, while in the case of prices it is 35 percent.

Among these firms, there appears to be a significant degree of synchronization in the timing of both price and wage changes, with significant clustering in January. Looking at the sectoral dimension, the variability in the application of regular, time-dependent rules to price revisions is quite remarkable, consistent with the wide dispersion found in the frequency of the revisions themselves. This indicator of relative wage rigidity corresponds to the respectively high and low frequency of wage adjustments found in the two countries (see section 1).

More generally, the percentage of firms adopting time-dependent wage rules is over 70 percent in Spain, the Netherlands, France and Greece and is generally much higher for euro area countries (61 percent) than for non-euro area countries ( 34 percent). , possibly related to the more widespread distribution of collective bargaining agreements and indexation clauses in the euro area. These country-specificities in the time patterns of wage change are confirmed by both micro-wage data available at an infra-annual level and by the analysis of collective agreements carried out in the context of the WDN (see Du Caju et al., 2008) ). which shows that the monthly pattern of wage changes is linked to the timing of wage negotiations.10 Some variation between countries can also be observed in the range of time-dependent prices, although less pronounced than in the case of wages (Figure 3). . 10 The peak in the frequency of wage change at the beginning of each year is also evident from other studies carried out within the WDN based on micro-quantitative data for a number of individual countries (Knell and Stiglbauer, 2008 for Austria; Heckel et al . , 2008 for France, Lünnemann and Wintr, 2008 for Luxembourg).

THE iNTERAcTiON BETWEEN WAGE AND PRicE ADJuSTMENT

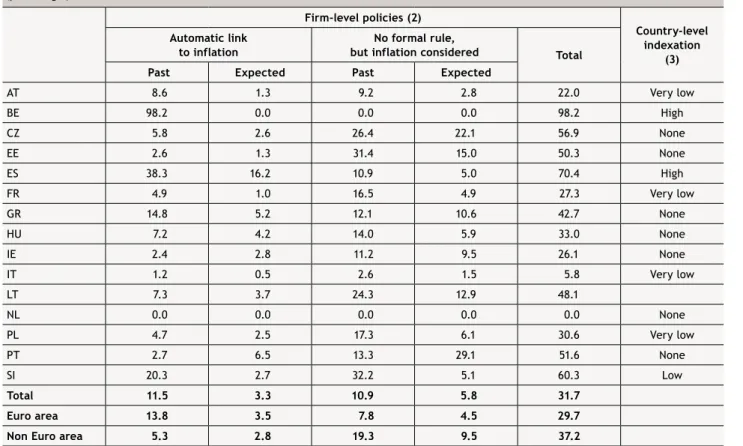

Greece is excluded from all calculations and in addition Italy and Spain are excluded in the event of a demand shock. Turning to the evidence regarding the impact of prices on wages, an important element is the extent and speed with which wage changes in firms are related to the overall inflationary outlook. Expected inflation is more important for wage determination than past inflation only in Portugal.12 In general, informal policies linking basic wages to inflation are more widespread in non-euro area countries than in euro area countries, while the opposite applies in the formal case. automatic adjustment mechanisms.

12 In the case of Germany, companies were not explicitly asked whether or not they implement a policy that adjusts changes in basic wages to inflation. 14 The data for Greece has a slightly different interpretation here, as the option 'never/don't know' was not allowed in the Greek questionnaire; the percentages are within the companies that actually change wages due to inflation. Finally, because a large number of the companies included in the WDN study operate in foreign markets, in order to identify the specific competitive pressures they face, we construct an indicator of the company's international exposure, expressed in share of exports in total turnover (question 27).

Share of labor costs in total costs − Evidence derived from studies conducted in connection with IPN, based both on information at the survey company level and on quantitative producer price microdata (see Fabiani et al., 2007, and Vermeulen et al., 2007) suggests a negative relationship between the incidence of labor on total costs and the frequency of price adjustments. 15 Based on the IPN results, questions on these more standard measures (number of competitors and market share) were not included in the WDN survey to reduce the burden on companies. In the research studies conducted within IPN, the indicator based on companies' response to competitors' pricing strategies was found to be highly correlated with the standard measures (see Fabiani et al., 2007).

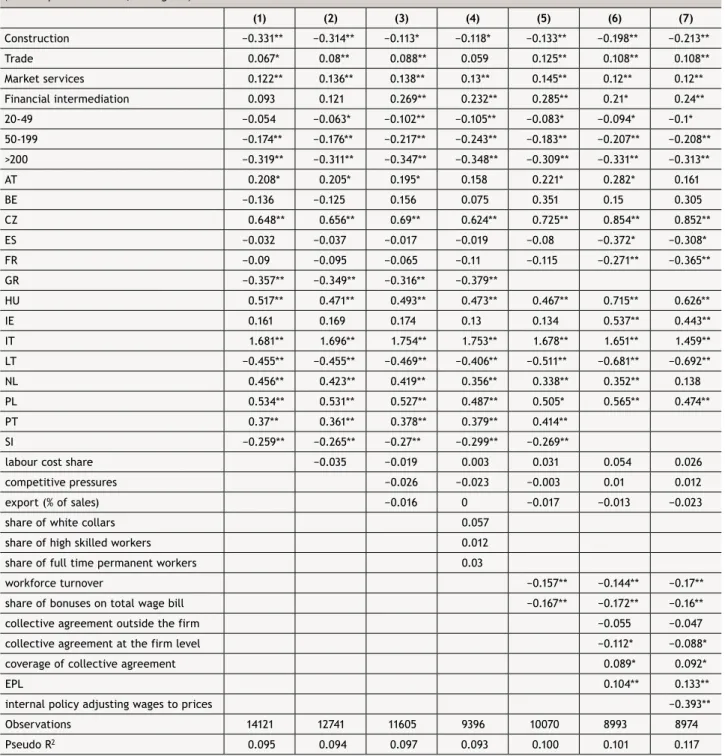

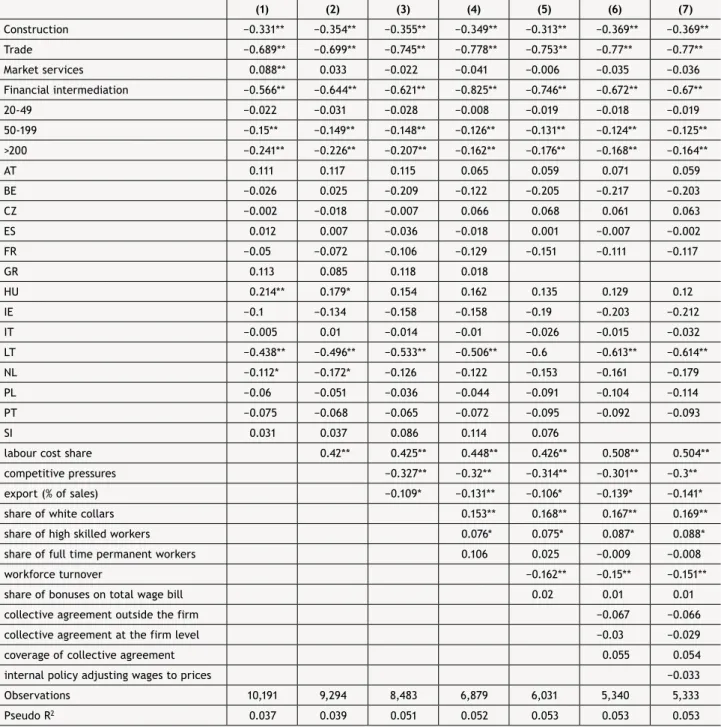

ORDERED PROBiT ESTiMATiON

Also for salaries, the value categories for the dependent variable increase in the degree of stickiness from 1 to 3, where 1=the company changes salaries more frequently than annually; 2= changes salary annually; 3=changes salary less often than annually. 16. For salaries, we also drop the last category ("never know/don't know"), which barely makes up 3 percent of the sample. In the regressions shown in the text, we take into account the frequency of wage adjustments due to any causes.

The composition of the labor force and the characteristics of individual jobs (column 4 in Tables 8 and 9) are important only for the level of price invariance, and the frequency of adjustment is negatively related to the share of highly qualified personnel and white-collar workers. The link between price and wage stiffness has long been studied in the economic literature (see Taylor, 1999 and Rotemberg and Woodford, 1999, also for a review of the literature). The empirical analysis described in the previous section suggests that there is indeed an interaction between price and wage invariance at the firm level.

On this basis, the instruments in the price equation (zpi) are our measures of the degree of product market competition, the exposure to foreign markets, the share of labor costs in total costs and some characteristics of the workforce at the company level. . Instruments in the wage equation (zwi) instead include the turnover of the companies' workforce, the share of bonuses on the total payroll, the presence of collective agreements at company level, their coverage and the degree of employment protection. The cross-sectoral variation in the frequency of price regulation is large compared to wage regulation.

Second, 40 percent of firms recognize a link (formal or informal) between the timing of their wage and price adjustment decisions. Companies' price and wage setting in the context of unusually unstable economic and financial conditions is ongoing research.

9 − How often is the base wage of an employee who belongs to the main occupational group in your firm (as defined in question 1) typically changed in your firm. 14 − Has the base salary of some employees in your firm ever been frozen over the past five years. 15 − Has the basic wage of some employees in your firm ever been reduced over the past five years.

18 - NON-KEY Have you ever used any of the following strategies to reduce labor costs in your company? 21 − How important is each of the following strategies when your business faces an unexpected slowdown in demand. 34 − How many workers (including employees and other types of workers) did your company have at the end of the reference period.

37 - NON-KEY How the employees in your company were distributed according to the following age groups at the end of the reference period. 38 - NON-KEY How the permanent employees in your company were distributed according to length of service at the end of the reference period. 40 − What percentage of your company's total costs was due to labor costs in the reference period.

The frequencies reported in Section 2 make it possible to identify the duration of prices (for the firm's main product) and wages (for the firm's typical workers) using some additional assumptions. In connection with the study, price and wage duration can be interpreted as the time interval during which these variables remain unchanged. The information collected by examining the frequency of price and wage changes comes in categories that identify points (e.g., annual changes correspond to 12-month duration) and intervals on the support of the duration distribution.

Three such intervals require this assumption: a) expected wage duration if it is shorter than one year (frequency more than once a year); Note that the support of the lognormal is the positive real line fit to duration, and the shape of the histogram of point responses is close to the shape of a lognormal density function for both wages and prices. The distributional assumption is necessarily ad hoc, but it corresponds to a positive support of duration.

With these caveats in mind, we should think of the duration results as an approximation. 24 For the imputation exercise, we split the four high-frequency categories into one, for simplicity and to obtain identification from the upper-duration (low-frequency) part of the distribution—the latter makes sense because here only the upper. the duration point we want to impose. Note that just for the imputation exercise we deleted the shorter duration categories E[dp|dp>12] and no information was discarded about the eventual translation of frequencies into durations.

Such effects measure discrete changes in the probability of each outcome as the covariate increases by dx in the case of a continuous variable and by unit 1 in the case of dummies or count variables. KAmlAni (1997), “The Reasons for Wage Rigidity: Evidence from a Survey of Firms”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. PortugAl (2005), “Contractual wages and the wage buffer under different bargaining situations”, Journal of Labor Economics, vol.

Price determination in the euro area: some stylized facts from consumer price data”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.