Evaluation and Impact Assessment of Business Climate Development

With case studies from Small Business Development Policy and Regulatory Policy

Péter Futó

Evaluation and Impact Assessment of Business Climate Development: With case studies from Small Business Development Policy and Regulatory Policy

Péter Futó

Publication date 2011

This research was supported by the Hungarian 'Social Renewal Operational Programme' (Társadalmi megújulás operatív program) in the framework of the project „TÁMOP-4.2.1.B-09/1/KMR)

Table of Contents

Introduction ... vi

1. 1. Evaluation and impact assessment activities: industry or science? ... 1

2. 2. Research design of impact assessment and evaluation studies ... 2

1. Conceptual framework ... 2

2. Components of research design ... 4

2.1. The research question ... 4

2.1.1. Research questions of impact assessments ... 4

2.1.2. Research questions of evaluations ... 5

2.2. The underlying theory: impact mechanism of SME development measures ... 7

2.2.1. The difficulties of a theoretical approach ... 7

2.2.2. Understanding how SME development measures function ... 8

2.3. The type of data to be collected ... 9

2.3.1. Qualitative studies ... 10

2.3.2. Sampling strategies for quantitative impact evaluation ... 10

2.3.3. Compromises and pitfalls in sampling ... 11

2.4. The use of data in order to make inferences ... 12

2.4.1. Qualitative approach: comparing causal and evaluative inference ... 12

2.4.2. Inference based on highly aggregated quantitative data ... 13

2.4.3. Inference in quantitative impact studies using micro data ... 14

2.4.4. Pitfalls of impact assessments ... 17

3. 3. SME Development Policy ... 18

1. SME development policy and its impact mechanisms ... 18

1.1. The rise of small business development ... 18

1.2. Special features of SME development in Central and Eastern Europe an transition countries ... 19

1.3. The relationship between SME policy and other policy fields ... 21

2. Evaluation of SME development projects, programmes and policies ... 23

2.1. Project and programme level evaluations ... 23

2.2. Case study ―SME Employment": Survey for evaluating subsidies given in order to enhance the employment capabilities of SMEs ... 28

2.2.1. Policy context: harmonising employment and competitiveness priorities in small enterprises ... 28

2.2.2. Purpose and method of the evaluation ... 30

2.3. Case Study ―SME Innovation". Assessment of a subsidy scheme facilitating SME innovations ... 41

2.3.1. Policy context: the relationship between innovation policy and SME development ... 42

2.3.2. Purpose and method of the questionnaire based evaluation ... 43

2.3.3. Results of the questionnaire-based survey [bib_18] ... 48

2.4. Policy level evaluations ... 50

3. Revealing the effects of factors that are exogenous for SME policy ... 53

3.1. Explaining the business climate ... 53

3.2. Comprehensive business surveys ... 54

3.3. Business demography analyses ... 55

3.4. Case Study ―Balaton": The use of small enterprise surveys in regional enterprise development ... 56

3.4.1. Purpose, genre and method of the research ... 56

3.4.2. Policy context: local embeddedness of SMEs and the role of tourism in enterprise development ... 58

3.4.3. Tourism in the region of Lake Balaton ... 60

3.4.4. Dependence of local SMEs on tourism ... 61

3.4.5. Company demographic indicators ... 62

3.4.6. Results of the questionnaire-based survey ... 64

4. 4. Regulatory Policy ... 69

1. The quality of the legal environment of enterprises ... 69

2. Assessing the aggregate impact of the administrative–regulatory environment ... 70

2.2. The OECD Economic Regulation Index ... 73

2.3. The ―Doing Business" project of the World Bank ... 74

2.3.1. Purpose and method ... 74

2.3.2. Selected results of the research ... 76

3. Impact assessment of individual regulations ... 77

3.1. Use, application fields and institutionalisation of RIA ... 77

3.2. Conceptual framework of RIA ... 79

3.3. Data collection for regulatory impact assessment ... 80

3.4. Analytical methods of impact assessment ... 81

3.5. Simplified regulatory impact assessments ... 84

4. Projects and case studies of Regulatory Impact Assessment ... 86

4.1. Regulatory Impact Assessment in the central organisations of the EU ... 86

4.2. Regulatory Impact Assessment in Western European member states of the EU .... 89

4.2.1. United Kingdom ... 89

4.2.2. Netherlands ... 91

4.2.3. Belgium ... 91

4.2.4. Germany ... 92

4.2.5. Sweden ... 92

4.3. Regulatory Impact Assessment in Central and Eastern Europe ... 92

4.3.1. Impact assessment culture in Hungary ... 95

4.4. Assessing the administrative environment of enterprises in the USA ... 96

4.4.1. Regulations reducing bureaucracy and their implementation ... 96

4.4.2. Impact of the federal regulations on small enterprises in the USA ... 98

4.5. Case Study ―Croatian RIA": Introducing EU technical regulation in Croatia ... 100

4.5.1. Policy context: legal harmonisation as part of Europeanisation process . 100 4.5.2. Research design ... 101

4.5.3. Results ... 102

4.5.4. Follow-up ... 104

5. 5. Conclusions and recommendations ... 105

A. 6. Appendices ... 108

1. Outlines of the questionnaires used in the case studies ... 108

1.1. Outline of company questionnaire used for SME labour subsidy evaluation (Case Study ―SME Employment") ... 108

1.1.1. Introductory text ... 108

1.1.2. Questions ... 108

1.2. Outline of company questionnaire used for SME innovation subsidy evaluation (Case Study ―SME Innovation") ... 113

1.2.1. Introductory text ... 113

1.2.2. Questionnaire ... 113

1.3. Outline of company questionnaire used for SMEs around Lake Balaton in Hungary (Case Study ―Balaton") ... 117

1.3.1. Introductory text ... 117

1.3.2. Questions ... 117

1.4. Outline of company questionnaire used for RIA on technical regulation (Case Study ―Croatian RIA") ... 121

1.4.1. Introductory text ... 121

1.4.2. Questions ... 122

2. Definitions - Glossary ... 123

3. References ... 137

4. Research, consultancy and educational projects mentioned in the text ... 143

BIBLIOGRÁFIA ... 148

List of Tables

2.1. Box 1. ... 12

3.1. Box 2. ... 24

3.2. Box 3 ... 26

3.3. Box 4. ... 27

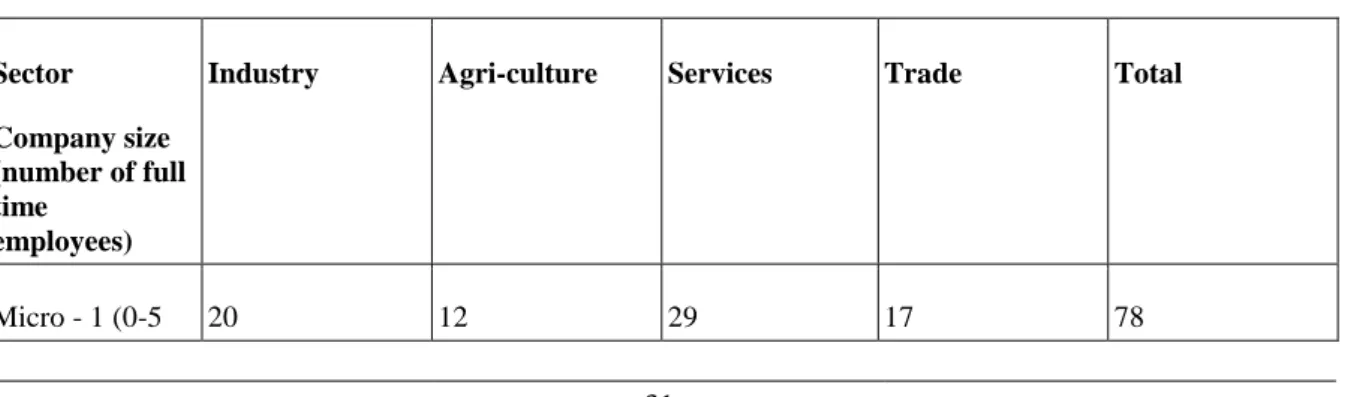

1. Distribution of supported enterprises by firm size and sectorNumber of enterprises ... 31

2. Distribution of refused enterprises by firm size and sector Number of enterprises ... 31

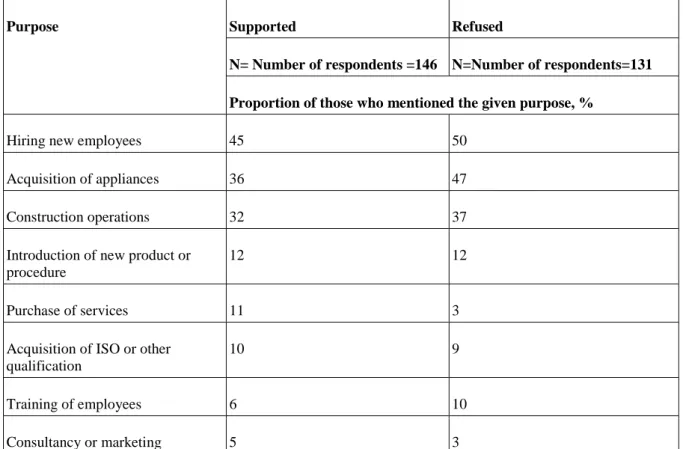

3. Purpose of the planned project as stated in the application document Respondents could select more than one option. ... 32

4. Why was the project needed? Content analysis of the responses of applicant enterprises ... 33

5. What has changed in your enterprise as a consequence of the support? ... 33

6. In what ways has the supported project improved your abilities to employ persons? ... 34

7. Changes following the implementation supported project ... 35

8. In what ways has the support improved the competitiveness? ... 35

9. What would you do differently today in implementing the project? ... 36

10. What would have happened if you had not received the support? ... 37

11. What would have happened if you had received the support? A content analysis of the answers of 132 refused enterprises in words ... 38

12. In which ways could the employment capability of Hungarian enterprises be improved? ... 38

13. In what ways could the competitiveness of Hungarian enterprises be improved? ... 40

3.17. Box 5. ... 43

14. The composition of responding enterprises by size classes ... 46

15. The composition of responding enterprises by legal form ... 46

16. The composition of responding enterprises by sector of their main activity ... 47

17. Does the company have a foreign owner or co-owner? ... 47

3.22. Box 6. ... 51

3.23. Box 7. ... 52

18. The distribution of small- and medium enterprises around Lake Balaton according to their size Balaton Region, 2000 ... 62

19. The distribution of small- and medium enterprises around Lake Balaton according to their sector of activity Balaton Region, 2000 ... 62

20. The distribution of small- and medium enterprises around Lake Balaton according to small regions Balaton Region, 2000 ... 63

21. The distribution of small- and medium enterprises around Lake Balaton according to the type of settlement where the premises of the enterprises are located Balaton Region, 2000 ... 63

4.1. Box 8. ... 85

4.2. Box 9. ... 93

4.3. Box 10. ... 93

4.4. Box 11. ... 94

22. Estimated value of compliance costs caused by federal regulations United States of America, 2004 99 4.6. Figure 9.: Simplified scheme of impact mechanism of European legislation for ensuring the free movement of goods ... 100

23. Significance of various impacts of the Low Voltage Directive in Croatia ... 103

Introduction

The climate of business, also called the environment of business activity is an invisible, complex and elusive concept. However, if the business climate of a country becomes beneficial, it has very spectacular and measurable consequences in terms of lively market places, the number new firms entering the market each year, the share of new high-growth firms and an increasing attractiveness of the country for foreign investors.

Business climate is a term which indicates how business development is supported by state, regional and local policies, by local communities, how business-to-business networks and labour relationships facilitate business activities. A good business climate allows businesses to conduct their affairs with minimal interference from authorities, while enabling the access to high quality inputs and to customers at low costs, offering investment possibilities with few risks and higher returns when compared to other places. 1

New firms are created by a combination various factors, such as the availability of skilled people, access to capital and the existence of promising business opportunities where risks are outweighed by expected benefits.

Analogous factors affect the growth of firms and the decisions of foreign investors. These factors can be affected by several different policy areas that are responsible for business climate development.

• The availability of skilled people can be affected by regulations that improve the functioning of the labour markets, by supporting the offer of business and technology services, moreover by the availability of training, with special respect to the spreading of entrepreneurial and management knowledge.

• The amount of capital can be positively influenced by creating a good legal and institutional framework the capital markets, and by offering government supported loans and loan guarantees can affect available for entrepreneurs.

• Business opportunities are also affected by regulations, e.g. regulation of entry into different sectors of the economy, administrative simplifications for start-ups, government control on business activities, access to international markets, bankruptcy legislation, by regulation of transfers of knowledge from universities.

Business climate development - as any other policy area - is regularly evaluated. The decision makers of various government agencies, business organisations and also taxpayers in general need regular feedback on the performance of measures taken in order to improve the business environment. Evaluations can address the whole strategy, or may focus on a particular set of measures such as a subsidized project, a campaign, a programme or a regulation. The resulting evaluation reports should offer insight and expert opinion on whether these interventions were successful in terms of various criteria such as relevance, efficiency, effectiveness, impacts and sustainability. In particular, if the evaluation report focuses on the issue of impacts, i.e. to what extent the events following the policy measure can be attributed to the assessed intervention itself, then the report is called an impact assessment.

Out of the various areas of business climate development, this book focuses on better regulation and small business policies. Further studies are under preparation on the application of evaluation and impact assessment in other policy fields of business climate development.

The book offers various analytical instruments that can be applied in research conducted on business climate development policies. At the same time, the substantive 2 dimension of the book provides analyses on specific strategies and instruments of small business development policy and regulatory policy.

• Methodological dimension. The book aims to systematically portray and to classify those methods of impact analysis and evaluation that have already become influential in policy making. These methods have been applied to assess the success or failure of projects, programmes and regulatory measures, ranging from small business development policy, regional development policy, environmental policy and other fields. These methods will be placed into an institutional context by giving an overview about those international, national and regional donor organisations and public services that have institutionalised and routinely apply these methodologies in order to obtain feedback about their development activities. Special attention is paid to

1The OECD has defined the following areas of business climate development: Investment Policy and Promotion, Privatisation Policy and Public Private Partnerships, Tax Policy, Trade Policy and Facilitation, Policies for Better Business Regulation, SME Policy and Promotion, Anti-Corruption, Corporate Governance, Business and Commercial Law, Conflict Resolution, Infrastructure, Human Capital Development Policy. [OECD 2010]

2 Substantive in this case means non-methodological aspects, i.e. related to particular policies, programmes and projects.

those conditions in which evaluation and impact assessment have been introduced in the region of Central and Eastern Europe, with some focus on Hungary. The methodological components of this book are not specific to any policy area, since some of these methods may be applied for a wide variety of policy fields.

• Substantive dimension. The book focuses on the application of impact analysis and evaluation in SME development policy and regulatory policy. In the case studies we examine the functioning of these methods in Central and Eastern European transition countries.

• SME development policy. A wide range of supportive and regulative, direct and indirect SME development instruments are presented that facilitate the access of SMEs to finance, business development services, certain factor inputs such as labour and technology and to output markets. The case studies highlight various aspects of the historical transition process of creating a viable and strong SME sector in various countries. The case studies were selected with a view of demonstrating how SME development is interdependent with various other policies ranging from innovation policy through labour policy to regulatory policy.

• Regulatory policy. The case studies devoted to regulatory impact assessment discuss the efforts of Central and Eastern European countries to harmonise their legislation with that of the European Union in order to create well functioning product markets and to institutionalise the free movement of goods.

The structure of the book is as follows.

• Chapter 1. gives an overview about the status of evaluation and impact assessment activities within the current practice of development policy and discusses evaluation reports in the contexts of consultancy and applied social science.

• Chapter 2. offers a methodological framework for doing research or consultancy work by using evaluation and impact assessment methods. The differences are shown between the genres of (a) impact assessment, which is a causal explanation of policy interventions and their perceived or expected consequences, and (b) evaluation, which is an act of assessing the value of these policy interventions against certain criteria. A coherent family of research designs has been constructed that includes both causal explanations and value judgements. The components of research design are identical for both quantitative and qualitative studies.

These models are applicable to the analysis of regulations, projects, programmes or policies as well.

• Chapter 3. first explains the emergence of SME policies internationally and in particular in the post- communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. SME development policies are positioned in the context of governance and public administration. The chapter proceeds with the evaluation of subsidised projects, support programmes and SME development policies. It is explained how to transform the abstract criteria of evaluation (e.g. relevance, efficiency, effectiveness, sustainability and others) into concrete questions of structured interviews or questionnaires. Finally methods for assessing the impact of exogenous factors (e.g.

historical events, regional endowments, business cycles and infrastructure developments) on SME development are presented.

• Chapter 4. presents various analytical tools of regulatory policy. The major instrument is regulatory impact assessment, a method for assessing the expected effects of individual regulations - or those of families of interconnected regulations – on enterprises and other stakeholders. The chapter presents the types of impact assessment systems that have been established and institutionalised in the developed countries and promoted by international organisations, such as the European Union or the OECD. Special attention is given to regulatory impact assessment (RIA) projects implemented in the new member states of the EU and those with an ambition to become members of the EU. The chapter also analyses the overall business environment of countries or regions, i.e. the system of regulations, administrative measures and institutions. Systems of indicators are presented that measure the influence of business environment on the economy, based on the practice of the OECD and that of the World Bank.

Case studies and examples. Throughout the book, the methods, genres and approaches are demonstrated by short examples in numbered boxes and also by detailed case studies. The case studies and examples analyse real-life measures of the following policy areas:

• Legal approximation of technology-policy of the European Union in the candidate countries.

• Investment promotion by business-friendly regulatory reforms.

• Financial policies as exemplified by facilitating loans for capital to small- and medium size enterprises.

• Labour policy as exemplified by specific support schemes, encouraging the willingness of small- and medium size enterprises to increase and improve their activities as employers.

• Innovation policies as exemplified by the subsidising of innovative activities of small- and medium enterprises.

• Improving regional development policy by lessons learnt from a survey of small- and medium enterprises located in a given tourist region.

The Appendix offers an outline of the questionnaires used in the case studies. On the basis of the simplified questionnaires it is easy to reconstruct the data collecting activity of the researchers and consultants which, after all, constitutes the empirical basis of every impact assessment and evaluation.

Definitions. The glossary explains the terms used in the book.

Chapter 1. 1. Evaluation and impact assessment activities: industry or science?

Both evaluation and impact assessment projects have become regularly implemented routine tasks to be performed on behalf of governments and donor organisations. For this reason, some methodologists refer to them as ―industries" 1 Impact assessments and evaluations are products of administrative cultures. Experts are routinely producing these types of analyses in order to provide feedback about the expected or experienced success or failure of interventions. 2 Decision makers of every policy area rely on such analyses, including social policies, environment protection, fiscal policies and others.

In the particular case of small business development policies most impact assessment and evaluation studies refer to the impacts of regulations, programmes and projects, in particular to measures involving credit and guarantee provision, equity financing, developing enterprise culture, offering advice, assistance and training to SMEs in the domains of technology and management, moreover institution development and infrastructure development.

Institutionalised methodologies. During the past two decades governments and international donor organisations have issued a wide selection of evaluation and impact assessment methodologies and guidelines. These documents describe recommended or mandatory methods to be followed by evaluators and impact assessors of development measures. Sectoral methodologies apply to specific policy areas (e.g. environment protection, enterprise development, etc.) On the other hand, methodologies specifying a particular research design define certain evaluation and impact assessment genres, which have been applied by thousands of individual studies to a wide range of interventions and policy areas.

Consultancy or scientific research. In practice, evaluation and impact assessment are regarded as consultancy activities than scientific research. Consultants routinely produce large quantities of such reports in order to meet the needs of their donor clients. Scientific research institutions and academic bodies also issue a wide range of evaluations. Many of these reports are classified documents that can be read only by the donors and the experts and project managers of intermediary organisations and beneficiaries. 3 On the other hand, the final reports of most impact assessments will be placed on the websites of the beneficiary government or that of the donor organisation. Only a handful of evaluations comply with the high standards of scientific journals and will be published in such periodicals.

Applied social research. Evaluation and impact assessment, if performed properly, are activities that can be classified as applied social research or applied policy research. Evaluation relies on the same methodological principles as political science. The difference between evaluation and political science is analogous to the difference between sociological research on the one hand and public opinion research and market research on the other hand.

Evaluators must use the techniques of applied social science in order to arrive to objectively verifiable inferences. The paradox and the challenge of evaluation is that evaluators can obtain the most valuable information from stakeholders lacking objectivity due to the fact that they are interested in continuing and expanding the evaluated programme at the same time: in most cases these are the initiators, managers and beneficiaries of the programme.

The techniques of evaluating policy interventions and measuring their effects are in a constant change, thus they cannot be regarded as fully developed yet. The views concerning the utility, necessity and best ways of obtaining feedback about measures are mixed with ideological elements. In most countries the relevant stakeholders of the public sector insist to use the traditional solutions and procedures of evaluation and impact assessment already tested and institutionalised. It is the big international organisations, think tanks and donors of aid programs which do their most for the unification, standardisation, development and spreading of the culture of impact assessment and evaluation.

1[Conlin-Stirrat 2008]

2 [OECD 2007]

3 E.g. the so-called „interim evaluations" of projects co-financed by the Phare Fund of the EU.

Chapter 2. 2. Research design of impact assessment and evaluation studies

1. Conceptual framework

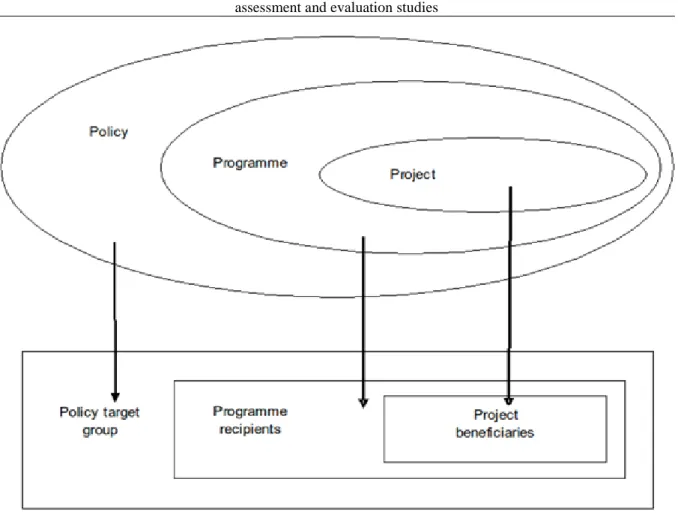

From projects to policies. The research design of evaluation and impact assessment projects depend strongly on the nature and the aggregation level of the examined intervention. The methods used for policy evaluation are substantially different from those methods that are used for project evaluation or those applied in regulatory impact assessment exercises. The concept of programme is wider than that of a project, and the concept of policy is wider than that of a programme. [bib_1]

The following classification of small business development policy measures helps to clarify these differences.

• Individual regulations may directly and indirectly influence the performance of small businesses. An example of an individual regulation supporting SMEs is a law on penalising late payment in supplier-buyer relations.

Such a measure, if implemented properly, creates equal opportunity for subcontractors, which in most of the cases are smaller companies than their clients.

• Wider families of regulative measures may also serve the needs of small businesses. Examples of such interventions are offered in deregulation campaigns, regulatory simplification reforms or legal harmonisation measures which may reduce the transaction costs of small enterprises when doing business.

• Individual projects have become the most widespread building blocks of aid delivery. Non-governmental agencies, governments and international donor organisations finance or co-finance tens of thousands of projects yearly involving training, consultancy, credit provision, direct non-returnable financing of SMEs, institution development or infrastructure development.

• Programmes are smaller or larger aggregates of more or less homogenous projects serving similar purposes.

The aggregate of projects affecting a specific sector, or having identical objectives can be called a programme. In SME development a typical programme is the provision of micro-credits, consisting of several thousands of smaller individual projects, each of them facilitating the start-up or investment activities of a particular beneficiary SME.

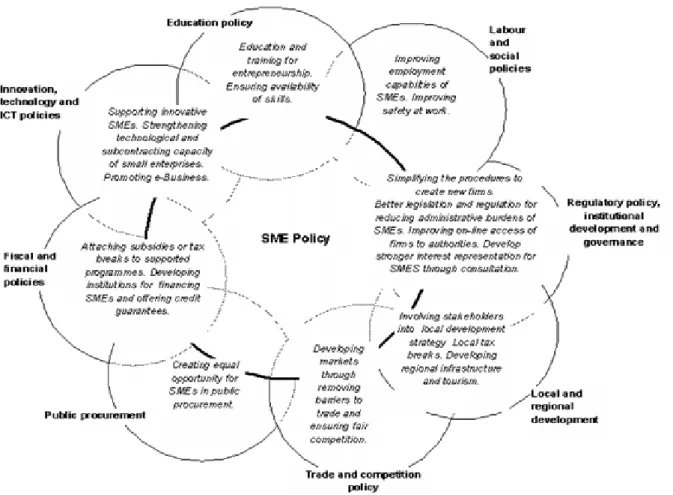

• Policies are the joint aggregates of the above mentioned types of measures on the national, regional or local level. In particular, SME development policies are strongly interrelated with other policy fields. Policies are built up from subsidised projects and programmes and frequently the delivery of policies is supported by legal measures and the respective institutional development as well. Policies are more than a simple sum of programmes, because they are characterised by higher level strategies, involving aims and priorities of a more abstract nature than those of the individual projects or programmes.

Target group. Policies, programmes and projects are implemented on behalf of a certain target population. In the particular case of SME development the target population can be selected as a well defined subgroup of small businesses, such as start-ups, potential subcontractors, innovative firms, companies in lagging behind settlements, etc. In case of support programmes these firms are also called eligible or final beneficiary companies. Alternatively, in case of indirect support the members of the target group are intermediary organisations such as government agencies, financial intermediaries or business development service providers.

Figure 1. The interrelationship between policy, programme, project and their target groups

Typology of consequences of policy interventions. Impact assessments may focus on specific types of impacts.

• Economic impact assessments highlight the impact of the examined intervention on companies in general, or on winners and losers among bigger and smaller companies, moreover consumers and government budgets.

• Social impact assessments focus on those impacts of decisions that affect certain social groups, such as women, minorities, unemployed people or immigrants, entrepreneurial stakeholders or the social stratification in general.

• Environmental impact assessments are revealing the impacts of a decision on the environment-friendly behaviour of various stakeholders on the pollution of air, water or soil, on the level of noise or vibration, or on waste management strategies of companies, households or institutions.

Impact assessments and evaluations can be applied before the intervention (ex-ante) or after the measure (ex post). Ex-ante analyses should deliver estimates about the expected future feasibility features, outcomes and consequences of a yet non-realised intervention.

Opinions, ratings, indicators. The success or failure of policy interventions is judged (a) by their outcomes and (b) by attributing these outcomes to the necessary resource inputs, e.g. subsidies or efforts. The attained outcomes may be interpreted in terms of resource inputs or of previously intended outcomes.

Impact assessors and evaluators make an extensive use of project indicators which can be used as empirical bases for formulating statements about causal relationship and ratings ranging from „highly satisfactory" to

„unsatisfactory". Indicators should have the following properties: (a) indicators are relevant if they are expressing the major properties of the program being evaluated (b) indicators are reliable if they are biased with as little measurement error as possible. Moreover, (c) it should be possible to obtain the data necessary for the computation of the indicator.

Quantitative characteristics. In most cases inputs and outcomes are measured by quantitative indicators. The use of quantitative indicators enhances the objectiveness of evaluations. In many cases a double set of measurements is needed „before" and „after" the implementation of the assessed intervention. However, the

Specific considerations and analyses are needed to attribute the changes to the assessed policies. Such indicators may refer (a) either to the final beneficiary SMEs by showing the improvement in terms of turnover or productivity or (b) to the regions in which the beneficiary SMEs work, by showing the impact in terms of poverty reduction or unemployment, or (c) to the intermediary organisations that deliver the intervention for the final beneficiary SMEs: in case of microcredit organisations such indicators may show the proportion of SMEs repaying their debt in time.

Qualitative characteristics. In many cases the outcomes of interventions can be measured only on a qualitative level. The report of an expert commission on entrepreneurial culture may consist of qualitative statements, since this phenomenon is hardly quantifiable. Qualitative rating is frequently the result of a comparative effort, e.g.

the impact of an assessed regulation can be rated as a success if its outcomes are better than the outcomes of a previous attempt to regulate this field. Or, a reform of the SME support system may be rated by the stakeholders as worse than the analogous interventions implemented in a neighbouring country.

The components of research design. A research design is a plan that shows how the researcher expects to use his/her evidence to make inferences. Research designs are composed of the following four major factors:

1. the research question 2. the underlying theory

3. the data and the sampling strategy for collecting the data 4. the use of data in order to make inferences. 1

In order to compile a theoretically well founded systematisation of the underlying methodologies of evaluation and impact assessment studies, it is useful to recognise these activities as applied research projects and to classify them according to their research designs. The rest of this chapter classifies analyses and compares the genres of impact assessment and evaluation by using the above mentioned four parameters of research design.

2. Components of research design

2.1. The research question

2.1.1. Research questions of impact assessments

It is the research question of the investigation that defines the differences between the genres of evaluation and impact assessment. While in case of evaluation one searches for the value of some policy intervention in relation to criteria defined earlier, in case of impact assessment the task is to reveal for some causal explanation about the expected impacts of a set of measures.

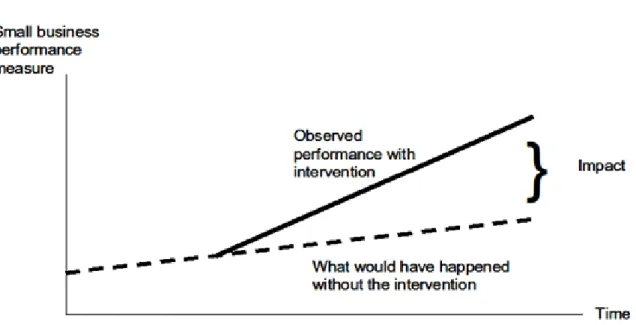

Impact assessments are analyses, explanations about the expected results and consequences of certain social- political interventions, policies and measures, based on empirical evidence. Therefore the research question of an impact assessment is always related to the existence and intensity of causal relations. In other words, impact assessors must demonstrate that the observed changes can be attributed to the measures examined or at least that these measures have contributed to them.

The definition of impact. Social researchers have, in connection with impact assessment, increasingly emphasised the requirement that impact assessments should apply the conceptual framework of causality as defined by social sciences. 2, 3 A researcher is justified to claim that a change that has occurred within the circle of affected enterprises is the consequence of a certain measure, if he or she clarifies first, what is regarded as a change and what are the key variables measuring this change. Theoretically, an inference about the existence of an impact of an intervention can be made only by comparing two scenarios: (a) the one in which the assessed measure was taken and (b) another scenario in which the measure was not taken. 4 One of these scenarios cannot

1 [King-Keohane-Verba 1994]

2 [Moksony 1999]

3 [Bartus and others 2005]

4 The previous sentence applies for the case of ex post impact assessment only. In case of ex ante impact assessment future tense must be applied: in this case (a) the scenario in which the measure will not be taken is compared with the scenario in which the measure will be taken.

be observed, and therefore it is called the counterfactual scenario. In some cases the impact of an intervention is measurable: this is the difference between the values of a key outcome indicator expressing change under the two scenarios.

Probabilistic impacts. The notion of impact can also be defined in probabilistic settings in the following manner: a cause raises the probability of an event, and the increase of this probability is the impact.

• In the framework of SME development policy this approach can be exemplified in the following interpretation: small enterprise development initiatives have positive impact to the extent that their implementation raise the probability of certain previously defined aims being attained among SMEs of the target group.

Complex structures of causes and impacts. In more complex settings causes and impacts can build up inter- dependent and interwoven structures. An example for such structure is the causal chain (the so-called "domino effect"). Another example for such inter-dependent causal structure is when a cause leads to the desired impact only if some other condition is also met (i.e. another cause, which alone could not trigger the desired impact) also occurs.

• An example for the ―causal chain" structure is the chain of non-payment, i.e. when each firm within a group of companies owes money to the previous one, and the bankruptcy of one company may trigger the failure of all other companies that follow this firm in the line of non-payment.

• An example for a more complex causal structure in SME development is the joint effect of a soft loan scheme and a credit guarantee scheme. The establishment of a soft loan scheme for start-up companies can facilitate the financing of these companies only if an affordable credit guarantee scheme is established as well.

The fundamental problem of impact assessment. Every impact assessment must cope with the basic problem of causal inference. Since the outcomes under the counterfactual (hypothetical) scenario are not observable, the comparison of the two sets of outcomes under the two scenarios cannot be based on a solid empirical basis. This leads to the so-called fundamental problem of causal inference, i.e. that causality is not directly observable.

However, a series of impact assessment methods have been developed to make indirect inferences to causality.

Examples of impact assessment research questions. The basic research question of impact assessments appears explicitly in the methodological apparatus of many impact assessments conducted about small business development measures.

• Research designs involving control groups may attempt to respond to research questions which tackle the difference between changes that have occurred in the beneficiary group and the control group. Example:

• Did the competitiveness of subsidy receiving beneficiary companies improve, in comparison with other, comparable, similar applicant companies that have not received subsidies?

• In case of research designs where no such control group can be constructed, the members of the target group can be asked about the difference between the observed and the counterfactual scenario. Examples:

• What would have happened to your firm if you had not received the subsidy?

What difference would it have made to your company, if you had received the required support?

You have hired two new employees since having received the subsidy: did you employ them as a consequence of having received the subsidy?

The government plans to introduce this regulation: will this be advantageous to your company or rather disadvantageous? Why?

2.1.2. Research questions of evaluations

Evaluation is a systematic determination of value, merit, and worth of interventions by using previously defined criteria or standards. Therefore the basic research question to be answered by evaluators is, whether the examined policy, programme or project is (or was, or will turn out to be) good or bad according to some criteria of success. Evaluators are expected to give their opinion about these interventions and in most evaluation cultures this opinion should be summarised in numerical ratings. Evaluators should judge the success or failure

those of other factors, and should find ways to improve the programme through a modification of current operations.

Evaluations are supposed to deliver expert opinions and the corresponding ratings about the success or failure of interventions, about the positive and negative characteristics of laws and enforcing organisations, about the advantages and disadvantages of aid delivery regimes.

Evaluations are prepared not only in order to establish the impact of policies and programmes. Such studies inform decision makers and taxpayers about the allocation of public funds. Evaluations may facilitate the improvements in the design and administration of programmes if these reports are used as feedback into current policy making and stimulate informed debate.

Impact assessments as part of evaluations. Evaluations of policies, programmes or projects are frequently revealing causal relations between interventions and outcomes. However, evaluators are expected not only to name the consequences and assess the extent of the expected impacts but also to evaluate these impacts whether they are satisfactory or not. Evaluation reports should answer not only the question of whether interventions or treatments work, but also a wide range of questions about when, how, under what circumstances the impacts occur, and what lessons can be learned from this particular intervention. And besides naming, assessing and evaluating impacts, evaluations must give an account of the relevance, efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of the examined intervention.

In order to account for this complexity, the genre of impact evaluation or impact assessment has been complemented by the methods of process evaluation as well. While the methods of impact evaluation are identical with those of impact assessment, process evaluation is a form of monitoring designed to determine whether the measures under the policy have been delivered as intended to the targeted recipients. Process evaluation (also known as implementation assessment) can be based on an analysis of the attitudes and behaviour of beneficiaries as they interact with the donor organisation or with the intermediary organisation during their involvement in the programme. 5

Process evaluations. In many cases impacts are not the priority focus of the evaluation project, rather the major aim of the researchers is to qualify the design and the process of aid delivery, e.g. the administrative and client service work of the intermediary institutions on behalf of the beneficiaries.

Examples of research questions of evaluations. The basic research question of evaluations appears in the methodological apparatus of many evaluations devoted to small business development measures. These questions are directly or indirectly concerned with the evaluation criteria against which the measure has to be assessed.

• Relevance . You have financed from the subsidy a new technology which you have recently introduced in your firm: do you consider this an innovation?

• Efficiency . Why were the results of your project delivered with such a big delay?

• Effectiveness . Have the training materials of the subsidised course been published on the Internet?

• Impact . Who else is going to profit from the subsidised project besides your company?

• Sustainability . The development of the Enterprise Resource Programme IT system of your company has been co-financed by the donor organisation. What kind of contractual guarantees has your company received from the contractor software developer?

The fundamental problem of evaluation is that it inevitably leads to normative statements. Evaluation judgments explicitly or implicitly involve statements about which aims, strategies, project designs or outcomes are good or bad, which operations are right or wrong. 6 Since project and programme evaluation is regarded as an exercise in applied social science, and evaluators arrive to value statements, it raises the issue of value in social science. 7 The main question connected with value statements is to what extent these can be verified of falsified. However, in case of project and programme evaluation, the findings are expressed in form of so-called

5 [Purdon – Lessof – Woodfield – Bryson 2001]

6[House 1999]

7 [Szántó 1992]

instrumental statements, which qualify certain lines of actions according to whether they are suitable to reach some previously defined aims or not. Such statements are combinations of norms and scientific statements and can be supported (if not proven) with the help of empirical data and with the application of a valid inference mechanism.

The opinions, conclusions and recommendations of evaluators influence decisions either (a) by affirming and encouraging certain procedures or outcomes for policies, regulations, projects programmes, or (b) by defining other procedures or outcomes as anomalies, discouraging policy makers to take these directions. Although evaluators increasingly use a wide range of data and a large apparatus of descriptive models and explanations to justify their judgments, however, a certain risk of arriving at subjectively or even emotionally influenced opinions still remains. Evaluation scores express normative judgments and it is nearly impossible to create universal, rationally applicable standards for all domains of evaluated activities. In principle there is no way to attain a perfectly rational falsification or proof for evaluation findings.

2.2. The underlying theory: impact mechanism of SME development measures

2.2.1. The difficulties of a theoretical approach

Evaluations and impact assessments rely either explicitly or implicitly on certain underlying substantive principles, on social, economic and political theories. These theories may be explained in text or can be stated in form of a quantitative model. Researchers promoting the method of so-called „theory-based evaluation (TBE)"

maintain that it is not sufficient to assess the impacts of a programme by proving that certain outcomes can be attributed to the program: rather, evaluators must be able to explore and explain how and why these measures have lead to success or failure. Theory-based evaluations explain the mechanisms of the determining or causal factors judged important for success, and how they might interact. The results of a theory-based evaluation should be converted into ―lessons learnt" and recommendations, moreover, the design and implementation of the programme should take into consideration the revealed underlying impact mechanisms. Based on these insights, it can then be decided which steps should be monitored as the programme develops. 8

While the aims of SME development are analogous to the aims of other fields of local, regional or national development policies, the instruments of this policy field, the professional content of policy interventions on behalf of small businesses covers a wide range of heterogeneous activities. Major examples of policy instruments are as follows:

• Creating an enterprise-friendly regulatory framework.

• Setting up, closing down, or reforming public agencies in order to offer up-to-date services for enterprises.

• Setting up loan guarantee schemes

• Programmes to encourage young disadvantaged individuals to start businesses.

• Programmes to encourage graduates to start businesses.

• Creating of Science Parks, small business incubators and promoting links between universities and SMEs.

• Granting tax relief for business angels 9.

• Enhancing investment and innovation readiness of SME owners.

• Encouraging SMEs to export.

• Subsidising new technology based firms.

• Subsidising management training.

8 [WB 2004]

9A business angel is an informal investor, usually a successful entrepreneur, who is willing to invest in high-risk, high-growth firms at a very early stage, and adds value by supplying hands-on business advice as well.

investing or relocating to these areas.

• Developing regional clusters and local innovation systems.

• Promoting rural entrepreneurship.

• Promoting business networking.

• Promoting Enterprise Zones.

There is a wide body of available theories to explain the role of public policies in SME development. Evaluators apply certain financial models in order to describe the decrease of transaction costs for SMEs as a result of certain policy interventions. 10 In other cases evaluators of institution development projects may apply general principles of organisational sociology in order to explain the impacts of these interventions (e.g. of decentralisations or regionalisations) on SMEs. Theories about the dissemination pattern of innovations can be applied in order to explain the spreading of e-business or e-government applications among small enterprises.

However, it would be nearly impossible to apply uniform, standard theoretic principles for modelling the impact mechanisms of all types of policy interventions on behalf of SMEs.

2.2.2. Understanding how SME development measures function

In spite of the lack of a widely accepted theory of SME development, experts responsible for the planning of small business policies, moreover the evaluators and impact assessors of these measures invariably apply certain general laws and principles of development economics.

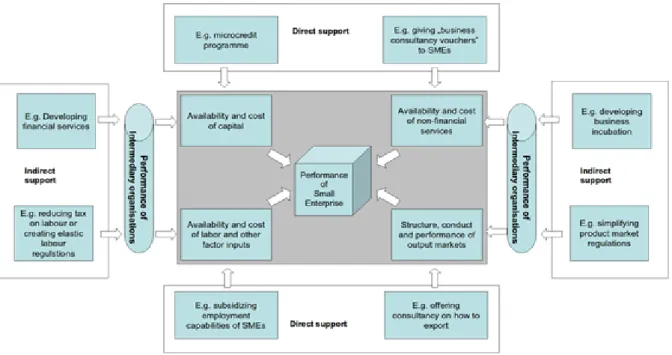

The performance of small enterprises depends on a wide range of factors. These factors can be classified according to the following system 11:

• the availability and cost of financial resources such as credits and venture capital,

• the availability and cost of non-financial business development services,

• the availability and cost of factor inputs such as labour, technology, knowledge and some locally scarce natural resources (e.g. water or energy), and

• the access to the markets of the outputs of companies (including product or service markets).

Impact mechanisms of SME development measures. Policy makers make use of the fact that the availability and the costs associated with the use of the above mentioned factors may be influenced by support policies and by reforming the legal and regulatory environment. In order to influence the development of SMEs through the above four factors, donor organisations have implemented the following types of initiatives or approaches:

• Developing financial services. This approach involves debt and equity financing which is facilitated through offering credit lines to intermediaries such as financial institutions; financial services are developed by subsidised consulting and training, and some subsidy schemes facilitate direct investment into small enterprises. Donors choosing this approach support banks, leasing organisations, credit guarantee services and other financial organisations such as local microcredit delivery organisations in order to support SMEs in an indirect manner. The impact of these interventions is exerted through the reduction of the costs of investments made by SMEs.

• Facilitating the delivery of business development services. This approach involves the direct delivery or the subsidisation of consulting, training, management or marketing services on behalf of SMEs. The access to business development services may be facilitated by grants and vouchers offered for SMEs. Donors choosing this approach support consultancies as intermediaries to develop the respective services in order to support SMEs in an indirect manner. The impact of these interventions is exerted through an increased use of business development services by SMEs.

10 [Kállay 2005]

11[Oldsman – Hallberg 2002]

• Improving the business environment. This approach involves the simplification of business regulations, reinforcing property rights and the enforcement of contracts, fighting corruption, improving the policies responsible for labour, trade and taxes. Donors choosing this approach support government agencies, professional associations and non-profit organisations in order to support SMEs in an indirect manner. The impact of these interventions is exerted through the reduction of the transaction costs of doing business, the costs of entering and expanding new markets for SMEs.

Intermediaries . Indirect programmes supporting the SME sector involve also a wide range of intermediary organisations.

• Government agencies. Support to SMEs is often provided indirectly by seeking to improve the regional and local business environment in which SMEs operate, and such programmes may target local and regional governments in order to reach the final beneficiary small businesses. Programmes aiming at simplifying the regulative and administrative environment of companies must first reach the central, the subordinated and the decentralised government agencies by re-organising them, developing their e-government capabilities and training their employees.

• Financial intermediaries. Programmes granting preferential credits for small companies must first motivate banks and train bank employees. Micro-credit programmes are delivered through several types of intermediaries such as banks, professional associations or local small business development foundations. The delivery of preferential credit schemes are frequently accompanied by establishing and subsidising loan guarantee organisations. Loan guarantee schemes are preferred instruments used by governments to intervene in the credit markets.

• Business development service providers. Some programmes aim at developing the capacity of SMEs to become subcontractors of multinationals. The resulting projects involve a wide range of technical consultants, such as engineering companies. Other programmes developing the e-commerce capabilities of SMEs are delivered with the help of software consultancy companies.

Figure 2. Schematic impact mechanism of SME interventions 12

2.3. The type of data to be collected

Evaluations and impact assessments are empirically based efforts. Research designs are thoroughly influenced by the choice of information sources, by the availability of data and by the strategy of collecting the necessary data.

12Own compilation, based on [Oldsman – Hallberg 2002].

2.3.1. Qualitative studies

In most research situations the access to qualitative data is easier and cheaper than to perform a questionnaire based quantitative survey among beneficiary companies. In case of studies are based on qualitative data, inference is based on the analysis of aid delivery documents, on interviews made with owners and managers of affected companies, with officials of regulatory agencies, or conducted with project managers of the aid delivery process. Causal inference is frequently based on the comparison of ―cases", i.e. on the secondary analysis of previous studies made in comparable countries where the same interventions have not been taken, or by analysing the effects of previous comparable interventions in the same country or in other regions. Quite frequently, qualitative studies made by international organisations compare countries: in such cases the implementation and reception of similar or analogous interventions – e.g. subsidy schemes, regulatory reforms, campaigns, etc. – is being compared. In qualitative studies the issue of sampling arises as the proper selection of (a) cases to compare, (b) documents to analyse and (c) interview subjects to visit.

Interviewing some representative members of the target group. Most impact assessment studies rely on a small scale sample of in-depth interviews made at companies affected by the examined policies. Sampling strategy as a rule is restricted to having a quota of at least one or two company of each type in the sample. For example, researchers may collect interviews from companies of various sizes, sectors and legal forms, and firms working in various regions and settlement types should also be represented. The collected empirical material contains important information about company characteristics, strategies and behaviour, about the awareness of companies of the examined policy intervention and their responses to the examined measures, about the opinions of experts and stakeholders about the institutions responsible for SME development. The results of these in-depth interviews are then contrasted with each other, classified by explanatory variables and aggregated. Inference to causal statements is made by asking the interviewed experts, regulators and enterprises about the counterfactual: what is their opinion about ―What would happen (or what would have happened) if the intervention did not take place (had not taken place)". While this method is relatively cheap, flexible and feasible, it can be easily biased by subjectivity or by lack of skills on the side of the interviewers.

2.3.2. Sampling strategies for quantitative impact evaluation

Quantitative impact assessments are prepared with the ambition to make statistically reliable statements about the relation of the cause (i.e. the policy intervention) and its consequences: about their impact exerted on companies. These efforts are always based on business surveys.

The sampling strategy of rigorous quantitative impact assessments of SME development measures consists of the following stages: (a) statistically defining the enterprise population that is the target group of the measure (b) selecting a sample of enterprises affected by the measure and (c) selecting a comparable sample of other companies, that have not been exposed to the measures. If possible, data collection from "treatment" and

―control" companies is repeated both before and after the intervention – this is called a ―before-after design".

The literature of this body of policy research often uses the language of experimental design used for medical research: the companies exposed to the intervention are called the ―treatment group" and a comparable group of companies that has not been exposed to the intervention is called the ―control group". In such studies the statistical inferences result in impact statements that refer to the ―treatment group", but these statements are on based on a comparison between the ―treatment group" and the ―control group".

However, due to lack of data, lack of resources or because of ethical reasons, it is not always possible to involve a control group into these research efforts. In such cases the inference about the causal relationship (i.e. the connection between the measure and its impacts) is weaker.

The following sampling strategies have been routinely applied in quantitative impact assessment designs. These designs have been ordered by the decreasing reliability of the causal explanations that can be based on them. On the upper end of this scale, the random selection of both the treatment group and the control group is considered to yield the most credible impact statements. The other extreme is when there is no control group at all: although such a sampling strategy is perfectly justifiable in case of descriptive studies, but any inference to impacts or causal relations can be made only if it is strongly reinforced by additional qualitative information which has been gathered independently from the quantitative data collected by the survey.

(1) Random assignment. This experimental design is used to measure the observed results of the intervention by comparing (a) a random selection of enterprises having been exposed to the intervention with (b) a random selection of enterprises not having been exposed to it. This sampling strategy is the so-called ―randomist"

approach. Although this approach leads to impact statements that have very high reliability, there are some

ethical, methodological and feasibility considerations against its use. Since regulations and subsidies have well defined target groups, it is not feasible or not ethical to experiment with companies by randomly choosing a

―treatment" and a ―control" group. Researchers are not in the position to decide, by way of random choice, which enterprises should receive subsidies or which companies should be exempted from the force of a regulation.

(2) Matched control group. In this case the control group is not randomly selected, but is constructed to be as similar as possible to the group affected by the intervention. Similarity is attained by selecting a control sample of companies of which the composition by size, sector, region and other important explanatory variables are identical with that of the affected group.

• In most cases this is ensured by using company quotas according to some previously selected explanatory variables such as sector, size and region.

• Another approach to matching is called ―matched area comparison design". In this case the outcomes in the pilot area – i.e. where the intervention is introduced – are compared with a control group that is chosen by picking enterprises of another, comparable, possibly similar area (e.g. region) where the intervention is not implemented.

• In more sophisticated cases a better match can be achieved by computing the so-called ―propensity scores".

Propensity score is the conditional probability that a company will be supported (―treated"), given the set of its values on the explanatory variables. Each company in the supported (―treated") group is matched to a subject that has a similar propensity score in the untreated group. The control group consists of the non- beneficiary companies selected by this method.

(3) Treatment group and control group selected by convenience . In the practice of SME development policy evaluation, company samples are very often determined by the willingness or capability of companies to respond to the questions of evaluators.

Examples of this approach are those research designs where the responses of a group of responding beneficiary companies are compared to the responses of those applicants who were applying unsuccessfully to the same subsidy scheme. This research design is somewhat biased for two reasons. (a) Voluntary respondents do not necessarily represent properly the target group. (b) Companies that have applied to the subsidy but were rejected by the selection committee have performed weaker during the application process and are not comparable to the beneficiary group. Consequently, by aggregating their responses the researchers cannot directly respond to the counterfactual question ―What would have happened without the intervention?" 13

(4) Research design without control group . In many situations of SME research interviews are made with - or questionnaires are collected from - only the companies affected by the intervention. In other words, the research design involves no control group. Certain causal statements with weaker reliability can be formulated even in such cases, by comparing internal sub-groups of the target group. This type of inference can be facilitated by the following sampling strategy: a sample with the possibly highest variability should be compiled. A high variability can be attained if the sample includes companies from various sectors, regions, size classes and levels of exposure to the (planned) intervention. 14

For example, let’s suppose that some previous qualitative information supports the hypothesis that the positive impact of the examined intervention is proportional to the size of the beneficiary company. If the empirical findings show that the expected positive changes do not occur among small companies, but do occur among medium sized enterprises, and even more so among bigger companies, then this might be interpreted as a reinforcement of the hypothesis.

2.3.3. Compromises and pitfalls in sampling

The range of data to be collected depends strongly on the financial resources available for the evaluation or impact assessment project. Research projects can save significant costs by applying weaker principles to sampling strategy. Such compromises might be unavoidable, but in such cases the report must (a) unanimously point out the lower reliability of the causal statements that it has arrived at and (b) should refer to the direction of the possible bias. The following methodological pitfall demonstrates how poor sampling can lead to biased impact statements.

13 E.g. Case Study C in this document.

14 E.g. Case Study A in this document.

the members of the target group of the intervention. This mistake is committed if the researcher examines the change that was brought about by a previously implemented intervention only in that group of companies in which the positive effect of the intervention was able to exert its influence.

Table 2.1. Box 1.

Example of selection on the dependent variable Bankruptcy regulations in Hungary

An example of bankruptcy research should illustrate the consequences of selecting the sample on the dependent variable. In the early 1990s in Hungary the transformation crisis has lead to an unusually high number of indebted companies. Long chains of non-payments have evolved, whereby each company in the chain was indebted to the next one. One of the causes of this anomaly was that the country lacked a well functioning bankruptcy law. Consequently a series of laws and regulations were issued with the aim of ensuring orderly bankruptcy procedures, giving chances of recovery to the indebted companies, but at the same time defining fair rules of liquidation in order to assure that the creditors – their clients, the state, other companies and banks - will be compensated by the assets of the indebted companies.

Two years later an evaluation was made about the interventions implemented in favour of those companies that got into troubles. The evaluation was based on a survey among surviving companies and among companies being still under liquidation procedure at the time of the survey. Only a handful of those companies were included in the sample that have been already liquidated between the bankruptcy regulations and the survey date. The reason for this omission was that at this time only a few managers could be reached who were able to speak about the liquidated companies.

The evaluation report clarified that (a) the sample of the survey had been selected on several of the dependent variables, i.e. the survival of companies and the length of the liquidation procedure; (b) the impact statements were somewhat biased, because the results of the examination could not be generalised to the full population of enterprises that were under the impact of the law.

The consequences of the lack of quantitative data. Researchers preparing quantitative impact assessment studies always face resource and the data constraints: surveys are expensive and data obtained from official statistics are in most cases outdated or irrelevant. In most research situations the group of enterprises affected by the examined intervention constitutes an aggregate of very specific character which does not correspond to any one of the widely used statistical categories of economic sectors, company size classes or geographic regions. For this reason, many researchers are compelled to adopt ad hoc methods by combining the use of qualitative data with the available quantitative data obtained from statistical offices, by doing a secondary analysis of previous surveys and by doing interviews by using a project-specific questionnaire.

In most cases it is the lack of available data that reduces the applicability of quantitative evaluation research methods 15 rather limited in their actual working practice. Due to a chronic lack of statistical data, impact assessments and evaluations related to the entrepreneurial sector do, in practice, depend on document analysis, on administrative and company interviews which are complemented by business surveys and by official statistical data in favourable cases only. Most guidelines of existing impact assessment and evaluation cultures do not count on the availability of relevant time series or survey data.

2.4. The use of data in order to make inferences

2.4.1. Qualitative approach: comparing causal and evaluative inference

Inference in qualitative impact studies. Qualitative impact studies make causal inferences by comparing detail- rich descriptions of carefully selected cases according to some previously defined sets of criteria.

The cases which offer themselves for comparison may be of the following types. In comparative qualitative research the researchers come to conclusions about impact mechanisms by studying various comparable items:

15 [Mohr 1995]