Anikó Báti

RENEWAL PROGRAMME FOR SCHOOL FOOD IN HUNGARY

(Báti, Anikó PhD is a senior research fellow in Hungarian Academy of Sciences Research Centre for the Humanities Institute of Ethnology since 2009. Her current fieldwork of interest include questions concerning recent foodways, lifestyle, and the eating habits. She is leader of the interdisciplinary research group focused on school canteens is Hungary. The project supported by National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary. bati.aniko@gmail.com)

Childhood obesity is a major public health challenge today.1 Cultural and economic differences influence the type and quality of school lunches provided for children throughout Europe.

School lunch makes a substantial contribution to children’s total energy and nutritional intake.

Therefore, there are efforts being made amongst governments, schools and parents, to improve the nutritional value of school lunches.

In my paper I give a brief overview of the role of public catering for children (aged 3–

6; 6–14 in kindergarten and in elementary school) in the food culture in Hungary, with special emphasis placed on the regulation governing the operation of the system, changes currently being made, and problems still to be solved. I seek an answer to the question of whether school meals can become a model contributing to the spread of healthy eating habits. What opportunities and obstacles are there for this in Hungary today? The sources I have used for my paper are the findings of international and Hungarian surveys by health and nutrition authorities, as well as my own fieldwork on the topic. I carried out a two-year micro study in a kindergarten and in a school in Budapest’s 20th district and in the kitchen of the catering firm supplying the meals. I also involved the parents in this exercise and I examined everyday nutrition in some of the families. The questions I raised in my research were principally directed at factors influencing eating habits that are given less attention in national surveys.2

1 Childhood obesity prevalence in Hungary, 2009-2010 (From: WHO 2014):

7 years old boys 25.1% overweight (including obesity); 14.2% obese 7 years old girls 28.2% overweight (including obesity); 11.3% obese

2 In previous studies of school cafeterias, which focused primarily on foods and their nutritional consistency, there was little room for social science research in the quest for solutions. Anikó Báti conducted ethnographic fieldwork- based research in Budapest. The foodways research approach – which focused on eating, personal preferences, and the school-and family-dining habits of children – sought answers to questions that were hitherto absent from nutrition research because of their methods and objectives. Following the publication of the research results, the district government incorporated the latest evidence and recommendations into the reform of the planned cafeteria programme. In the school studied, both the maintainer and the parents took more interest in the cafeteria and started

Since 2006, WHO Europe offers a tool to develop corresponding school nutrition programmes.3 In 2011, the Hungarian Chief Medical Officer developed recommendations for age-relevant nutritional requirements. Previously, there had not been any uniform requirement of this nature in Hungary, and the raw materials that could be used were not strictly regulated, nor were there rules formulated concerning the daily cost of food per capita. As a result, the standard of school meals varied widely depending on the type of settlement, in both towns and villages.

Nationwide surveys by the competent authorities (e.g. National Institute of Food and Nutrition) revealed a dramatic nutritional situation in children’s public catering in Hungary: e.g. very high levels of salt and sugar in the food provided, and little consumption of vegetables, fruit and fish.

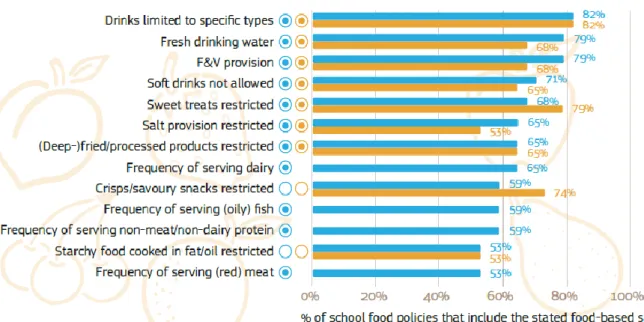

Local governments launched several programmes to reform school cafeteria meals.4 These efforts have become a nationwide programme,5 and school meal programmes are now also strongly supported by the government. In 2014, a mandatory regulation was introduced6 governing the operation of school meal services based on EU guidelines.7 The regulation is largely food-based, but it also contains a few nutritional rules (e.g. concerning energy, salt, sugar, fats, and calcium content). The regulation prescribes the number of meals, the size of portions, and the frequency of particular contents over 10-day periods. It restricts or bans certain foods and drinks. The regulation specifies that the weekly menu is to be published in advance and must display the main nutrition facts and any allergens that the food contains. The aim of the regulation is to reduce the level of nutritional risk factors in public catering.

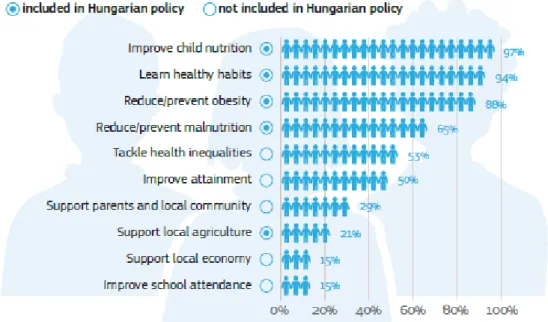

In 2014 the European Union summed up the public catering strategies of individual member countries8 and took steps for the reform of the nutritional impact of these strategies. It can be said that all member countries recognised the importance of the provision of balanced

a kind of dialogue about it. Thus, it became the first Hungarian applied ethnographic foodways research regarding public catering for children.

3 WHO Europe school nutrition programmes, 2006.

4 Surveys by the National Institute of Food and Nutrition: Országos 2008; 2009; 2013; 2017.

5The programmes focus mainly on very young children’s eating habits, and programmes focusing on teenagers have not been carried out in Hungary. As opposed to the Hungarian situation, in the United Kingdom, for example, there are many results based on research projects, which show the preferences of teenagers and young people related to socio-economic boundaries. See e.g. with other references: Wendy, J. W. et al. 2018, pp. 195–

206; Rachel L. T. et al. 2017, pp. 95–104.; Matalas, A. et al. 2012, pp. 237–245.

6 Mandatory Regulation: 37/2014. (IV. 30.) EMMI Rendelet.

7 European countries have created policy frameworks to govern these practices. A systematic assessment of national school food policies across the European Union plus Norway and Switzerland (n = 30 countries) was carried out. The survey revealed that all 30 countries currently have a school-food policy in place; a total of 34 relevant policies were identified, 18 of which were mandatory and the remaining 16 voluntary. Source:

https://www.eufic.org/en/healthy-living/article/school-lunch-standards-in-europe, retrieved 18.07.2018.

8 Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann, Kardakis, Wollgast et al. 2014, See more:

https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/.../lbna26651enn.p, retrieved 18.07.2018.

nutrition for children for the promotion of health, and in order to achieve this they regulated public catering. These measures were closely linked to the EU’s action plan on child obesity.9 When compared to the situation in Europe, Hungary’s regulation on public catering regulates the range of foods for consumption in quite a complex, mandatory and autonomous way. As a result, kindergarten and school meals now include dishes that are most appropriate for the needs of the different age groups and that ensure the healthy development of the children.

In conjunction with the regulation, a collection of recipes has been compiled and further training in this connection for workers in public catering has also been launched.

Fig. 1: Schoolfood policy objectives in Hungary in 2014 (Source: European Commission:

School Food Policy Country Factsheets Hungary, 2015).

9 See more: European Commission (2007).

Fig 2: Food-based standards in Hungary in 2014 (Source: European Commission: School Food Policy Country Factsheets Hungary, 2015).

However, there are also long-standing problems in the operation of public catering in Hungary that are not addressed by the public catering regulation in this form. These problems have a negative influence on the current view of school cafeterias (e.g. they are still a bad memory for the parents of today’s children), and, consequently, the regulation is less able to act as a model in shaping everyday eating habits in schools. In practice, there is a lot of waste, an indication that children do not like the foods served.

What are these still unsolved problems? I shall mention only a few of these as revealed by my investigation conducted in Budapest, using an ethnological approach,10 and I shall also briefly touch on the history of school cafeterias. In the second half of the 20th century, in the wake of political, economic and social changes in Hungary, the organisation of households also underwent change, as the two-earner family model became the predominant form in both towns and villages. From 1949 onwards, the state took over part of the provision of everyday care for children from families, as part of socialist social-policy measures. In kindergartens and schools, besides teaching, the provision of meals was also organised and made easily accessible for all.

Over the past decades around half of the 3–18 years age group regularly used this service.

(However, the remainder continued to have lunch at home or took sandwiches to school.)

10 See: Báti 2014, pp. 201–259.

The funds available for catering for children in kindergartens and schools were always very limited. This meant that, for the most part, the meals provided for lunch comprised soup and a main course high in carbohydrates with much use being made of potatoes and pasta, while the morning and afternoon snacks were based on bread. Few fresh vegetables, fruit or white meat, were served. Over a long period, there was no change in the recipes used. A recipe book was published for school cafeteria meals using cheap ingredients. As a result, not only the choice of dishes, but also their taste, was more or less the same everywhere. Consumers came to associate these foods and tastes with cafeterias. Some dishes, such as tomato soup, pasta with potatoes, or meat risotto, are still widely regarded as school cafeteria food, today. In many cases, the kitchen staff were untrained, they were paid low wages, and they received little recognition for their work. In most institutions, menus were not supervised by dieticians, and children ate the same food as adults. The cutlery, dishes and trays used in the cafeterias were cheap, mass- produced products, that became worn very quickly and, because of the way the dishes were washed, exuded a characteristic “cafeteria smell”. (That smell was the first thing mentioned by practically all my informants when recalling their memories of childhood school meals.) The extent to which this form of cafeteria became a model in Hungary was that it stressed the importance of regular daily meals and contributed to the spread of new dishes, such as vegetables in brown sauce.

After 1990, following the change of the political system the task of providing public catering for children, together with the kindergartens and schools, as well as the responsibility for kindergartens and schools themselves was transferred from the state to local authorities.

Then in 2014, the state, as the financing body, took back the funding of the schools but not the task of operating school cafeterias. This division created a serious problem, both for jurisdictions and budgetary matters. As was the situation in the past, the local authorities still cover only part of the costs of operating the school cafeterias as most parents have to pay for meals. Exceptions are made for the socially needy and large families, who are entitled to free meals in the institution even outside school hours – during the summer holidays, for example.

The standard of the catering services provided varies widely from one settlement to another, in both towns and villages depending on the resources available. There is no uniform minimum funding to cover the costs of meals in kindergartens and schools. The local authorities either have the lunches cooked in kitchens that they operate or they have a contract with private entrepreneurs to do so. Only a minority of the staff working in the kitchens are qualified for the type of work they perform. For technical reasons, only a few places are able to provide for special dietary needs, such as gluten-free meals.

In the larger towns and cities, communication between the school, the children, the parents, and the firms providing the service, is minimal. Complaints or feedback about the food often do not reach those concerned with its provision. The situation is better in the smaller villages where the local community also has control, has some an influence on the operation of the cafeteria. In such places, thanks to the direct contact existing among villagers, it is easier to manage operation of the school cafeteria by involving local farms.

From the viewpoint of children eating at the cafeterias, one of the key problems is the limited amount of time available for the meal.11 While surveys have found, that in European practice, lunchtime ranges from 35‒75 minutes, the corresponding figure in Hungary to date has generally been 15‒30 minutes. This is only the length of the break between two classes.

And most of that time is spent standing in a queue, leaving little more than a few minutes for the actual meal. The school cafeterias are generally crowded. But because of the limited space and the class schedule this is the only way schools can organise meals. Many children decide to leave out the soup from the two-course menu offered for lunch or to eat only a small part of the food, so that they can finish on time. This is one of the reasons why there is a lot of waste.

Figs. 3–4: Children standing in a queue during lunchtime in the school canteen (Photo: Anikó Báti, Budapest, 2013).

11 Regarding the importance of the time available for the meal, see e.g., Bhatt 2014, pp. 656–676.

Fig. 5: Catering for children aged 3–6 years in a kindergarten (Photo: Anikó Báti, Budapest, 2014).

Catering for children aged 3–6 years in kindergarten is much better than the situation in the schools. The children are more willing to eat the same foods and there is less waste. The secret of this success is that healthy nutrition occupies an important place in the teaching programme.12 Children learn the basics of gardening through play, taste the produce in the kindergarten and while on excursions. During the daily sessions they learn to eat properly with a knife and a fork, and how to set the table. However, these basic skills and knowledge are soon lost when they begin school where meals and food hardly appear at all as part of the teaching programme. Nor does the way the cafeteria is used favour continuation of the processes begun in the kindergarten. Only a very few schools have a training kitchen where children could learn to cook as the preparation of food is not part of the school curriculum. The cafeteria can only help to make children conscious consumers if the processes begun in the kindergarten are successfully integrated into the school curriculum.13

As I observed the home, family-made meals of children who eat in the schools I was struck by how little information parents have about the cafeteria meals. They do not ask their children about the meals and they do not follow the school menus. The families I examined generally eat an evening meal together on weekdays, not all families serve cooked food and, when planning meals, they do not take into account what the children eat at school. At the same time, the accustomed tastes brought from home, basically determine children’s attitudes to cafeteria dishes in school. In compliance with the regulation, cafeterias strive to reduce salt

12 On food socialisation see: Arnaiz 2009, pp. 191–215.; Mikkelsen 2013, pp. 412–415.; 2014, pp. 1191–1193.;

Haden 2006, pp. 265–274. On the notion of foodscape used to describe our food envioments and which impact food choice, see: Mikkelsen 2011, pp. 209-216; Barbro et al. 2009, pp. 25–51; Brembeck, Barbo 2010. pp. 797–

818.; Morgan, Sonnino 2008.

13 National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition published a website about the canteens to give parents, teachers, and the staff, a share in information and news, recipe and so on. See https://merokanal.hu/

retrieved 10.1.2019.

consumption for example. This means that the foods lack the tastes which children are accustomed to at home, and they find the cafeteria meals insipid. In the absence of suitable communication about and information on the situation from the shool, neither the parents nor the children are able to accept this innovation. Practically all parents wrap a mid-morning snack for their children (a sandwich, baked goods), even if the child eats at the cafeteria, and, strangely, the children also take a drink with them from home because even access to drinking water is not solved in many schools.

These few examples are perhaps sufficient to show that public catering in schools in Hungary in its present form is unable to act as a model representing the basic principles of healthy nutrition. For that to happen, among other matters, the theoretical and practical aspects of nutrition should be better incorporated into school education, as has already been achieved in the kindergartens. In order to map the functional problems of cafeterias as reflected in family eating habits, and to elaborate, formulate solutions for the above issues, my research team, composed of ethnologists and dieticians, has begun a four-year interdisciplinary research project on the matter.

Across Europe, school lunch nutritional standards are the basis for improving nutritional intake of all school children. However, this will only be successful if pupils like, and choose to eat, these meals – this is an aspect that has been largely neglected in the development of school meals until now. Therefore, children are now being involved from the very start of foodservice planning, including taste-testing. Parents, too, are encouraged to be involved in school meal policies.14 Changes to the dining environment can also improve food choices, reduce queuing times, and support social interaction. Importantly, a focus on school meals should be part of a whole school approach to health promotion.

References Printed

Arnaiz, Mabel Gracia :“Learning to Eat. Establishing Dietic Normality in the Treatment of Eating Disorders”. Food, Culture & Society 12(2), 2009, pp. 191–215.

Barbro, Johanson (et al.): “Nordic Children’s Foodscapes.” Food, Culture & Society 1 (2009), pp. 25–51.

Brembeck, Helene ‒ Barbo, Johanson: “Foodscapes and Children’s Bodies.” Culture Unbound. Journal of Current Cultural Research. 2010. Vol. 2. 797-818.

14See: Kalafa 2011.

It is funny way to demonstrate the school food to children is a book of poems: Lackfi 2014.

Haden, Roger: ‘„Pandora’s Lunchbox” on Esthetic Education, Children, and Food.’

Food, Culture & Society 9(3) 2006, pp. 265–274.

Kalafa, Amy: Lunch Wars. How to Start a School Food Revolution and Win the Battle for Our Children’s Health. Penguin: New York, 2011.

Lackfi, János: Paradicsomleves betűtésztával. Etetős versek a menzáról Megyeri Annamária tálalásában. (“Tomato soup with pasta. Poems about school food with illustrations served by Megyeri, Annamária”). Betűtészta Kiadó: Budapest, 2014.

Matalas, Antonia-Leda – Lazarou, Chrystalleni – B. Panagiotakos, Demosthenes: “Meal Habits of Schoolchildren: Associations with Socio-Economic Factors.” In: Patricia Lysaght (ed.): Time for Food. Everyday Food and Changing Meal Habits in Global Perspective. Ĺbo Akademi University Press: Ĺbo, 2012. pp. 237–245.

Mikkelsen, Bent Egbert: “Images of foodscapes: Introduction to foodscepe studies and their application in the study of healthy eating out-of-home enviroments.” Public Health. 131(5), 2011, pp. 209-216.

Mikkelsen, Bent Egbert: “Can Healthy Eating at School be Considered a Human Right?” In:

Helena Röcklinsberg – Per Sandin (eds): The Ethics of Comsumption: The Citizen, the Market and the Law. Wageningen Academic Publisers: Wageningen, 2013, pp. 412–415.

Mikkelsen, Bent Egbert: “School – a Multitude of Opportunities for Promoting Healthier Eating.” Public Health Nutrition 17(6), 2014, pp. 1191–1193.

Morgan, Kevin – Sonnino, Roberta: The School Food Revolution. Public Food and the Challange of Sustainable Development. Eartscan, Taylor & Francis Group: London, 2008 Tyrell, Rachel L. et al.: Food environments of young people linking individual behaviour to environmental context. Journal of Public Health, 39(1), 2017, pp. 95-104.

Wendy J Wills et al.: “The Socio-Economic Boundaries Shaping Young People’s Lunchtime Food Practices on a Schoolday.” Children and Society 32, 2018. pp. 195-206.

Internet

Báti Anikó: “Paradicsomlevestől a fürjtojásig. A gyermekétkeztetés néprajzi vizsgálata budapesti példa nyomán” (“An Ethnogrphic Study on Children’s Nutrition in Budapest”).

Ethno-Lore 2014, pp. 201–259. See https://nti.btk.mta.hu/hu/evkonyv/131-ethno-lore-xxxi- 2014, retrieved 2.1.2019.

Bhatt, Rachana: “‘Timing is Everything’”. The Impacted School Lunch Length on Children’s Body Weight. Southern Economic Journal 80(3), 2014, pp. 656–676. See

http://www.jstor.org./stable/23809645, retrieved 23.01.2018.

European Commission: “White Paper on a Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity Related Health Issues”. OOPEC. 2007. See

http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/nutrition_wp_en.pd f, retrieved 18.7.2018.

European Commission: “School Food Policy Country Factsheets Hungary”. Joint Research Centre. 2015. See https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/jrc-school-food-policy-factsheet- hungary_en.pdf, retrieved: 31. 7. 2018.

Mandatory Regulation: 37/2014. (IV. 30.) „EMMI Rendelet”.

http://net.jogtar.hu/jr/gen/hjegy_doc.cgi?docid=A1400037.EMM (retrieved: 31. 07. 2018.) National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition: See https://merokanal.hu/

retrieved 10. 1. 2019.

“Országos helyzetkép az óvodai közétkeztetésről 2009” (“Nationwide School Lunch in Kindergartens Overview 2009”). See http://oeti.hu/download/ovoda2009.pdf, retrieved: 31.

07. 2018.

“Országos helyzetkép az óvodai közétkeztetésről 2013”. (“Nationwide School Lunch in Kindergartens Overview 2013”). See http://oeti.hu/download/ovoda2013.pdf, retrieved 31. 7.

2018.

“Országos iskolai MENZA körkép 2008” (“Nationwide School Lunch Overview 2008”). See http://oeti.hu/download/menza2008.pdf, retrieved: 31. 07. 2018.

“Országos iskolai MENZA körkép 2013” (“Nationwide School Lunch Overview 2013”). See http://oeti.hu/download/menza2013.pdf, retrieved: 31. 7. 2018.

“Országos iskolai MENZA körkép 2017” (“Nationwide School Lunch Overview 2017”). See www.ogyei.gov.hu/.../Orszagos%20iskolai%20MENZA%20körkep%202017%20web, retrieved: 31. 7. 2018.

Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann, S. ‒ Kardakis, T. ‒ Wollgast, J. et al.: “Mapping of National School Food Policies across the EU28 Plus Norway and Switzerland”. JRC Science and Policy Reports. Luxembourg, European Commission, 2014. See

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/lbna26651enn.pdf, retrieved 18.7.2018.

“WHO Europe school nutrition programmes, 2006.” See: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health- topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/publications/guidance-and-tools/school-age-children-and- adolescents/food-and-nutrition-policy-for-schools-a-tool-for-the-development-of-school- nutrition-programmes-in-the-who-european-region retrieved 10. 1. 2019.

“WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative”. WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014. See http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/258781/COSI-report- round-1-and-2_final-for-web.pdf, retrieved 18.7.2018.