ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Labour Economics

journalhomepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/labeco

Job loss, disability insurance and health expenditure

Anikó Bíró

a,∗, Péter Elek

a,baCentre for Economic and Regional Studies, “Lendület ” Health and Population Research Group, Hungary

bEötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary

a r t i c le i n f o

JEL classification:

C23 I12 I38 J63 Keywords:

Administrative data Disability insurance Displacement Health expenditure

a b s t r a ct

Weanalysethecausaleffectofjoblossondisabilityinsuranceenrolmentonafive-yearhorizonandtheimplica- tionsonhealthexpenditure.UsingadministrativepaneldatafromHungary,wefollowindividualsdisplaceddue toamasslay-off andcomparetheirlabourforcestatustonon-laid-off individualswithsimilaremploymentand healthhistory.Accordingtoourestimates,beinglaidoff increasesthetransitionprobabilitytodisability1.5-fold (orby1.4%points)infouryears,andhalfoftheexcesstransitionsoccurwithinthefirstyear.Thefour-year mortalityrateincreases1.7-fold(orby0.4%point).

Totaloutpatient,inpatientandpharmaceuticalexpenditureincreasethreefoldwhenalaid-off individualtakesup disabilitybenefit,anddecreaseslightlyafterwards,butdonotreachthepre-disabilitylevels.Themediumterm increaseinhealthexpenditurecorrespondsto20−25%oftheadditionaldisabilitypayments.Detailedmedication datashowthatphysicalhealthshocks,thediagnosisofchronicphysicalconditions,suchashypertensionor diabetes,andthedeteriorationofmentalhealthallcontributetotheobservedsurgeinhealthexpenditure.

1. Introductionandrelatedliterature

Theaimsofthispaperaretwofold:toestimatetheextenttowhich jobdisplacementincreasesparticipationinsocialprogrammesforthe disabled,andtheimplicationsonhealthexpenditure.

Thehighshareofworking-ageindividualsreceivingdisabilityben- efitsisamajorsocialandeconomicprobleminmanydevelopedcoun- tries. Liebman(2015)documents a substantialincrease in the share ofdisabilityinsurancerecipientswithintheworking-agepopulationin theUnitedStates,risingfrom2.2%inthelate1970sto4.6%in2013.

Banksetal.(2015)reportforGreatBritainthatthenumberofdisabil- ityrecipientsmorethandoubledfromthe1970sto2013.Accordingto OECDstatistics,5.6%oftheworkingagepopulationinOECDcountries receiveddisabilitybenefitsin2007(themiddleofourexaminedperiod), withmuchhigherthanaverageratesinHungary(12%),Sweden,Nor- way,FinlandandtheNetherlands(8−11%)(OECD,2009,Figure4.1).

Tomaketheproblemmoresevere,veryfewrecipientsofdisabilityben- efitsreturntothelabourmarket.

Consequencesongovernmentexpendituresaresubstantial.Accord- ingto Eurostat(2019), spending on disabilitybenefits amountedto 1.9%ofGDPintheEuropeanUnion (EU27)in2007.InmostOECD countries these expenditures are much larger than expenditures on anyother income-replacement programmefor working-ageindividu- als(OECD,2009).Itis,thus,ofgreatpolicyimportancetounderstand andpotentiallyreducetheemployment-relatedchannelsof disability

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:biro.aniko@krtk.mta.hu(A.Bíró),elek.peter@krtk.mta.hu(P.Elek).

claims.Suchreductionscannotonlyincreasetheemploymentrateof theworking-agepopulation,butcanalsohavebeneficialeffectsonthe publichealthcarebudget– apreviouslyundocumentedaspect,whichis thefocusofouranalysis.

Weknowfrompreviousliteraturethatjoblosshasalastingnegative effectonfuturelabourmarketposition(BöheimandTaylor,2002;Elia- sonandStorrie,2006)andaparticularlyscarringeffectonconsecutive earnings(Arulampalam,2001;GregoryandJukes,2001;Jacobsonetal., 1993;Ruhm,1991;amongmanyothers).Also,disabilityinsurancere- cipiencyhasasubstantialworkdisincentiveeffectonthebeneficiaries (e.g.ChenandKlaauw,2008;FrenchandSong,2014;Maestasetal., 2013).However,lessisknownabouttheeffectofjoblossontheuptake ofsocialsecuritybenefits.

If eligible,a displacedworker can claimunemploymentbenefits.

However,oncethebenefitperiodexpires,theindividualeitherhasto returntoworkorneedstosecureothersocialsecuritybenefitsso as toreceive some incomeandmaintain socialinsurance status.It has beenshownthatunemploymentbenefitsanddisabilitybenefitsareto someextentsubstitutes(KoningandVuuren,2007;KoningandVuuren, 2010fortheNetherlands;Bratsbergetal.,2013forNorway),although Riphahn(1997)(usingdatafromGermany)rejectsthishypothesis.

Theavailabilityofdisabilitybenefitsislikelytoaffectlabourforce status after a job loss. Indeed, as Autor and Duggan (2003) point out,thecharacteristicsofthedisabilityinsurancesysteminfluencethe propensityoflabourforceexitforworkerswhofacedadverseshocks.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101856

Received17September2019;Receivedinrevisedform18May2020;Accepted20May2020 Availableonline23May2020

0927-5371/© 2020TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense.

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Themore generousthe disabilitybenefitis,themore likelyitis for workerstoexitthelabour market.Similarly, Regeetal.(2009)and Bratsberg et al. (2013) show for Norway that job loss significantly increases the risk of disability benefit uptake. Looking at the pe- riodoftheGreatRecession,bothMaestasetal.(2015)andJiménez- Martínetal. (2018)find thattherecession hadanincreasing effect on disability applications, but due to the increased rate of denials, there is no cleareffect on the stock of disability benefitrecipients.

Scharle(2008) shows on county-level datafrom Hungary that local labourmarketconditionsarecorrelatedwithdisabilityinsuranceclaims.

Inthefirstpartofthispaper,wecontributetothisliteraturebyes- timatingthecausaleffectofjoblossondisabilityinsuranceenrolment andanalysingthetime-varyingpatternsofthetransitionratesbasedon individual-leveladministrative datafromHungarybetween2003and 2011.Toovercometheendogeneityofjobloss,weexploitmasslay-offs andmatchlaid-off tonon-laid-off workerswithpropensityscorematch- ing.Wethenfollowindividualsinthematchedsampleandobtainthat joblossimpliesa1.5-fold(orby1.4%points)highertransitiontodis- abilityinsuranceinfouryears.Halfoftheexcesstransitionsoccurwithin thefirstyear,andthetransitionprobabilityreturnstothevalueinthe controlgroupafteraboutthreeyears.

Theincreaseduptakeofdisabilitybenefitsafterajoblossmaybe amoralhazardissue.Asevidenceforthis,GruberandKubik(1997), DugganandGruber(2014)show thatdisabilityinsuranceplanchar- acteristicsanddenialrateshavestrongereffectsonthelaboursupply ofthehealthier,moreableindividuals;Campolieti(2002)showsthat thegenerosityofthedisabilitybenefitsystemaffectstheprevalenceof hard-to-diagnoseconditionsamongtherecipients.Ontheotherhand, theincreasedtransitiontodisabilitymayalsostemfromgenuinehealth shocksassociatedwithunemployment.Indeed,wefindthatthefour- yearmortalityrateincreases1.7-fold(orby0.4%point)asaresultof thelay-off,suggestingthepresenceofgenuinehealthshocks.

Disentanglingthemoralhazardandthehealthshockchannelsisnot straightforward,evenifdataonhealthcareuseorhealthexpenditureis available,becausenon-employmentmayaffectthedemandforhealth servicesthroughvariouspathways.First,unemploymentandinactivity mayhavedirecthealtheffects,althoughtheliteratureonitismixed(see e.g.Browningetal.,2006andSchmitz,2011fornon-significantresults;

SchallerandStevens,2015fornegativeaverageeffectsandSchieleand Schmitz,2016fornegativeeffectsonthoseininitialbadhealth).Second, evenifhealthstatusisconstant,non-employmentmayreducehealth- careusebecauseofthedecreasedincentivesforhealthmaintenanceand possiblybecauseofachangeininsurancestatus.Kuhnetal.(2009)and SchallerandStevens(2015)findlittleevidenceforanoveralleffectof joblossonhealthcareuse,althoughthelatterpapershowsthatdoc- toralvisitsandprescriptiondrugusagedecreaseifthelostjobwasthe primarysourceofinsurance.

Specifically,theapplicationforandmaintenanceofdisabilitybenefit mayhaveprofound,time-varyingimpactonhealthcareuse.Atthetime oftheapplication,healthcareusemayincreasebecauseoftheexpanded incentivesforbeingdiagnosedwithvariouschronicconditions,andalso becauseoftheneedtocheckhealthstatusduringthereviewprocess.

Afterwards,receivingdisabilitybenefitmayreduceincentivesforhealth maintenance,thusloweringhealthcareuse.

Inthesecondpartofourpaper,weexaminethesechannels,i.e.we analysetherelationshipbetweenhealthexpenditure– anindicatorof healthcareuse– andtheuptakeofdisabilitybenefit.Ourfocusison thehealthspendingofindividualswhoclaimdisabilitybenefitaftera jobloss.Suchaninvestigationisnovelintheliterature.Onewouldex- pectthatbecomingadisabilitybeneficiaryisassociatedwithincreased healthspendingbothduetopoorhealth(i.e.disability)andtotheappli- cationprocess,althoughlittleisknownaboutthemagnitudesofhealth spendingarounddisabilityuptake.

Accordingtoourresults,claimingdisabilitybenefitafterbeinglaid off isassociatedwithafivefoldsurgeininpatientanda2.5-foldsurge inoutpatientandpharmaceuticalexpenditure.Althoughtheexpendi-

turedeclinesaftertheuptakeofthebenefit,itdoesnotreachitspre- disabilitylevel.Moredetaileddataonmedicationcategoriesshowthat, beyondphysicalhealthshocks,thediagnosisofchronicphysicalcondi- tions,suchashypertensionordiabetes,andthedeteriorationofmental healthallcontributetotheobservedsurgeinhealthexpenditure.Thus, theincreaseindisabilityinsuranceenrolmentafterajoblossisneither purelyamoralhazardissuenorexclusivelyaconsequenceofgenuine healthshocks.Theseresultsextendandpartlycontradictthefindingsof Regeetal.(2009),whoidentifythementalhealtheffectofjoblossas thekeydriveroftheincreaseindisabilitybenefituptake.

2. Institutionalbackground

2.1. Disability,unemploymentbenefitandold-agepension

Thefollowingbriefsummaryofthedisabilityinsurancesystemin HungaryisbasedonMISSOC(2018),OECD(2012)andScharle(2011). Disabilityinsuranceinitscurrentformwasintroducedin1983.As partofthesocialsecuritysystem,disabilitybenefitsarepaidfromthe publicbudget.Duringthefirstpartoftheanalysedperiod(upto2008), peoplewithatleast67%incapacityforworkcouldapplyfordisability pension.Theamountofthebenefitwasinfluencedbytheaveragewage beforedisability,theincapacityratioandthelengthoftheinsurancepe- riod.Thereplacementratetypicallyvariedbetween40−65%.Eligibility terminatedifthepensionerwasnolongerincapableofwork,orworked onaregularbasis,earninganincomecomparabletowhatcouldhave beenearnedinthespecificoccupationpriortobecomingdisabled.Dis- abilitypensionrecipiencycouldstartimmediatelyafterthetermination ofemployment,withoutacompulsorywaitingperiod.Theevaluation ofclaimswasrathergenerous.However,aspublicspendingondisabil- itybenefitssteadilyincreased,governmentsbegantoacknowledgethe needforreform.Asaresult,rehabilitationallowancewasintroducedin 2008.Itispaidtoapersonwitharequirednumberofserviceyearswho suffersfrom50−79%damagetohealth(comparabletothe67%inca- pacityforworkintheprevioussystem),isunabletopursueaformerjob butiscapableofrehabilitation.Itis20%moregenerousthandisability pensionbutmaybepaidonlyforthenecessaryperiodofrehabilitation andforamaximumofthreeyears.Recipientsoftheallowancehaveto participateinacomprehensiverehabilitationplandevisedbytheem- ploymentofficewithaviewtorecovertheirworkcapacity.Thosewho sufferfromatleast50%damagetohealth,butforwhomrehabilitation isnotproposed,canapplyfordisabilitypension.

Ourdatadoesnotallowtodistinguishbetweenthesetypesofben- efits,sowewillexaminethemjointlyunderthename‘disabilityben- efit’.AccordingtoONYF(2012),whiletheaveragemonthlyamounts ofrehabilitationallowanceanddisabilitypensionweresimilarin2011 (around73,000HUF ≈ 233EUR),therewere305thousanddisability pensionrecipients andonly 25thousandrehabilitationallowancere- cipients,outofthetotalpopulationofaround10millioninHungary.

Evenbetween 2008−2011,whenthetwoschemesexistedsimultane- ously,therewere2.5-foldmorenewdisabilitypensionersthannewre- habilitationallowancerecipients.

Anapplication fordisabilitybenefitisevaluated byacommittee, whichconsidersthesocialcircumstancesoftheapplicantaswellasthe medicalevidencefordisability.Socialcircumstances,suchasaccessto publictransportation,caringresponsibilities,characteristicsoftheso- cialnetworkallinfluencewhetherrehabilitationisrecommended.1The medicalevidenceisprovidedbythegeneralpractitioner(GP),basedon certificatesanddischarge notesissuedbyspecialists,andpossiblyby hospitals.Thus,theprocessrequirestheinvolvementofbothprimary careandsecondarycarephysicians.Thecommitteethenevaluatesthe

1TheevaluationprocessisregulatedindetailbyDecree7/2012.(II.14.) oftheHungarianMinistryofNationalResources.Duringouranalysisperiod (2003–2011),theredidnotexistasimilardetailedregulation.

rateofincapacityforworkbasedonthemedicalevidence.Asimilarpro- cessexistsforthereviewofeligibility,whichoccursevery1−5years (dependingontheconditionoftheapplicant).Thisimpliesthattheap- plicationforandreviewofdisabilitybothincreasehealthexpenditure.

Intheanalysedperiod,theapprovalrateofdisabilityinsuranceappli- cationswasaround30%(ONYF,2012).

The system of disability insurance was again reformed in 2011, mostlyduetothehighpublicpaymentson disabilitybenefits andto theallegedwidespreadabuseofthesystem.Thenew,stricterlegisla- tioncameintoeffectin2012,whichisoutsideourobservationperiod.

Sincethen,disabilitybenefitsarenolongerconsideredtobepartofthe pensionsystem,butratherasatypeofsicknessallowance.

Amajorriskofthesystemisthat, despitethescreeningofappli- cantsfordisabilitybenefits,individualsmightstillusethemasasub- stituteofunemploymentbenefits.Overtheanalysedperiod(between 2003−2011),Hungaryhadatwo-tierunemploymentinsurancescheme.

Unemploymentbenefitinthefirsttierdependedontheincometheyear beforeunemployment,andcouldbereceivedfor,at most,270 days.

Aftertheexhaustionofthefirsttierofunemploymentbenefits,theun- employedcouldreceiveaflatamountofunemploymentassistancefor anadditional3months.Afterwards,low-incomeindividualscouldclaim welfarebenefits.

Upon reaching old-age retirementage, disabilitybenefits arere- placedby old-agepension. Hungaryhasamandatory,pay-as-yougo pensionsystem, wherepensionsarebased onearningsbefore retire- ment,andeligibilityisconditionalon20yearsofservice.Intheanal- ysedperiod, themajorityofindividualsretiredatthestatutoryearly retirementage,whichwas60yearsformenandincreasedfrom57to 59yearsforwomen.(Formoredetailsonthepensionsystem,seeBíró andElek,2018.)

2.2. Healthcaresystem

TheHungarianhealthcaresystem isasingle-payer system,where servicesarefinancedfromcontributionsandstatesubsidies,adminis- teredbytheNationalHealthInsuranceFundAdministration(NHIFA).

Thevastmajorityofindividuals– theemployees,theunemployed,the pensionersandthoseonvariousbenefits– areautomaticallyinsured(in thecaseofemployees,theemployersareobligedtopaythesocialinsur- ancecontributionsforthem).Soastoremaininsured,inactivepeople notbelongingtoanyofthepreviouscategorieshavetopayamonthly feeforhealthinsurancecoverage,however,thosewithlowincomeare stillexemptfromthepaymentofthefee.Thus,inpractice,joblossand subsequentlabourmarkettransitionshavenoeffectonhealthinsurance status.

Themajorityofhealthcareservices,includingbothoutpatientand inpatientcare,donotrequireco-payments,althoughinformalpayments arecommonforawiderangeofservices(Gaáletal.,2006;Szendeand Culyer,2006).Thisimpliesforourstudythatanyobservedincreasein healthexpendituremightbecoupledwithanunobservedincreasein out-of-pocketinformalpayments.Also,peoplewillingtoprovideinfor- malpaymentsmightbeabletocollectthemedicalevidencefordisability benefitapplicationfasterorcansecuremorefavourablemedicalevalu- ations.Peoplemayoptforusingprivatecare(whichwascommononly incertainspecialties;e.g.indentalcareorgynecology,duringtheex- aminedperiod)whentheyhavetopayfeefortheservices.Userfees formedication dependon theamount of subsidiesfromthe NHIFA, whichvaries greatlyacross substances.Onaverage,patientshaveto coverslightlylessthanhalfofthepriceofamedication:therestispaid bythesocialsecurity.AmoredetailedoverviewofHungary’shealthcare systemisprovidedbyGaáletal.(2011).

3. Data

Theempiricalanalysisis basedon aunique administrative panel datasetfromHungary.Thedatacoverarandomhalfofthe5−74years-

oldpopulationin2003,whowerefolloweduntil2011.Itwascreated bylinkingadministrativedatafrom theHungariantaxauthority,the pensionandthehealthauthorities,amongothers.2Inthisresearch,we concentrateonthe35−54yearsoldagegroup,whichincludesmostof thetransitionstodisability,butexcludesthevastmajorityofold-age pensioners.Bycuttingthesampleatage54,wefocusonindividuals ofactiveageandexcludetheanalysisofthechoicebetweendisability benefitandold-agepension.

Weusevarioussegmentsofthedataset.Gender,yearofbirthandset- tlementofresidence(correspondingtoyear2003)arerecordedforeach individual. Thelabour marketandbenefitsegmentcontainsmonthly informationonwages,employment,pensionandotherbenefitstatus.

Therefore,wecantrackonamonthlybasiswhetheranindividualwas employed, was a pensioneror receivedunemployment,disability or otherbenefits.Occupation(ISCO)codesofemploymentspellsarecol- lectedforemployees.Levelofeducationisnotobservedbutcanbeap- proximatedforeachoccupationcode(andthusforeachindividual)as themedianeducationlevelofworkerswiththesameoccupationinthe LabourForceSurvey.

Basedonourdataset,employeesofthesamefirmcanbeidentified.

Thesectoroftheemployer(publicorprivate)isalsoobserved.Thesize ofthefirmcanbeapproximatedastwicethenumberofitsemployeesin thesample,althoughthisestimateisnotveryaccurateformicro-firms.

Fig.1showstheratesofthemostimportantbenefitsbygenderand age.Theemployment rate(notshown inthe figure)is60−70%for males oftheexaminedages.Theratioofdisabilitybenefitrecipients increasesheavilywithageandgoesabove10%amongthoseaged50 andabove,whileunemploymentbenefitisreceivedbyaround5%of thepopulation atallexamined ages.Theratioof old-agepensioners (notshown)isbelow3%,evenamongthoseaged50−54.

Inthemainanalysis,wewillfollowthelabourmarketoutcomesof workerswhowerelaidoff duringamasslay-off,whichweconsideras aninvoluntaryjobloss.Aneventisclassifiedasamasslay-off ifthesize ofthecompanydecreasesbyatleast30%inagivenmonth,remainsbe- low70%oftheoriginalsizethroughoutthefollowingyear,andnomore than15%ofitsemployeesmovetothesameemployer.Variousdefini- tionsofmasslay-off havebeenadvocatedintheliterature,with30%asa widelyusedcut-off (seeHandwerkerandMason,2012foranoverview, andJacobsonetal.,1993;SullivanandWachter,2009forspecificex- amples).Ourmasslay-off definitionincludescompanyclosuresaswell.

Sincethesizeofmicro-firmscannotbedeterminedpreciselyinour50%

sample,weexamineonlythemasslay-offsofcompanieswithatleast fiveemployeesinthedataset(i.e.atleasttenemployeesonaverage).

InAppendixC, wecheck therobustnessof ourresultstotheuse of20%and40%dismissalratesinthedefinitionofmasslay-off,andto twoalternativedefinitionsofjobloss– companyclosure(includingearly leavers)andtheofficialdefinitionofcollectiveredundancyinHungary.

Themainresultsarequalitativelyrobusttothesealternativedefinitions.

Wemakethefollowingsamplerestrictions.Wefocusonindividu- alsaged35−54years,whowerecontinuouslyemployedinthelastsix monthsbyafirmwithatleastten(estimated)employees,anddidnot receiveunemployment,disabilityormaternitybenefitsinthelastmonth ofemployment.Weconcentrateonyearsbetween2005−2009toensure thatwehaveatwo-yearlonghistoryandalsoatwo-yearlongfollow- upperiodforeachindividual.Altogetherweexamine28,169laid-off workers,outoftheapproximately1millionworkersaged35−54years.

DescriptivestatisticsareprovidedinTable1.

Healthexpenditureisobservedontheannuallevelinthedataset.

Wehaveinformationontheannualpublicspendingonspecialistout-

2ThelinkeddatasetisundertheownershipoftheCentralAdministrationof NationalPensionInsurance,theNationalHealthInsuranceFundAdministration (NHIFA),theEducationalAuthority,theNationalTaxandCustomsAdministra- tion,theNationalLabourOffice,andthePensionPaymentDirectorateofHun- gary.ThedatawasprocessedbytheInstituteofEconomics,CentreforEconomic andRegionalStudies(CERS).

Table1

Descriptivestatisticsoftheemployed,thematchedmasslay-off andmatchedcontrolsample.

Employed Mass lay-off Control

Standardized difference (matched) (matched)

Mean S.D. Mean S.D. Mean S.D. (matched) Year

2005 0.202 0.402 0.173 0.378 0.173 0.378 0.0%

2006 0.201 0.401 0.161 0.367 0.161 0.367 0.0%

2007 0.202 0.402 0.152 0.359 0.152 0.359 0.0%

2008 0.201 0.401 0.253 0.435 0.253 0.435 0.0%

2009 0.193 0.395 0.261 0.439 0.261 0.439 0.0%

Male 0.464 0.499 0.538 0.499 0.538 0.499 0.0%

Age group

35–39 0.247 0.431 0.257 0.437 0.261 0.439 -0.9%

40–44 0.232 0.422 0.231 0.422 0.229 0.420 0.5%

45–49 0.244 0.429 0.237 0.425 0.236 0.425 0.2%

50–54 0.277 0.448 0.275 0.446 0.274 0.446 0.2%

Region (2003)

C Hungary 0.289 0.453 0.285 0.452 0.284 0.451 0.3%

C Transdanubia 0.127 0.332 0.130 0.337 0.128 0.334 0.7%

W Transdanubia 0.116 0.32 0.111 0.314 0.109 0.312 0.5%

S Transdanubia 0.091 0.287 0.083 0.277 0.083 0.276 0.1%

N Hungary 0.118 0.322 0.138 0.345 0.141 0.348 -0.8%

N Great Plain 0.137 0.343 0.141 0.348 0.146 0.353 -1.3%

S Great Plain 0.123 0.328 0.111 0.314 0.108 0.311 0.7%

Settlement type (2003)

Budapest 0.164 0.37 0.153 0.360 0.152 0.359 0.4%

County-level town 0.217 0.412 0.187 0.390 0.188 0.391 -0.2%

Other town 0.321 0.467 0.326 0.469 0.326 0.469 -0.1%

Village 0.298 0.457 0.334 0.472 0.334 0.472 0.0%

Estimated level of education (based on occupation)

Primary 0.140 0.347 0.207 0.405 0.206 0.405 0.2%

Lower secondary 0.377 0.485 0.544 0.498 0.543 0.498 0.2%

Upper secondary 0.276 0.447 0.172 0.378 0.173 0.378 -0.2%

Tertiary 0.207 0.405 0.077 0.267 0.078 0.268 -0.4%

Firm characteristics

Size 4811 8970 209 554 182 522 5.0%

10–24 employees 0.121 0.326 0.214 0.410 0.229 0.420 -3.7%

25–49 employees 0.079 0.269 0.183 0.387 0.196 0.397 -3.2%

50–99 employees 0.089 0.284 0.181 0.385 0.190 0.392 -2.3%

100–249 employees 0.113 0.316 0.172 0.378 0.170 0.376 0.6%

250–4999 employees 0.308 0.462 0.214 0.410 0.187 0.390 6.8%

5000- employees 0.292 0.455 0.036 0.185 0.028 0.165 4.4%

Size 1 year ago if non-missing 3831 7632 220 576 181 565 6.9%

Size 2 years ago if non-missing 3038 6454 167 479 141 516 5.2%

Size 1 year ago non-missing 0.852 0.355 0.795 0.404 0.791 0.406 1.0%

Size 2 years ago non-missing 0.727 0.445 0.595 0.491 0.572 0.495 4.6%

Government sector 0.292 0.455 0.030 0.172 0.027 0.161 2.3%

Labour market history, number of months

Employment in prev. 12 months 11.87 0.71 11.59 1.21 11.58 1.24 0.6%

Employment in prev. 13–24 months 11.36 2.21 10.31 3.50 10.18 3.66 3.7%

Disability benefit in prev. 12 months 0.003 0.14 0.007 0.22 0.005 0.20 0.6%

Disability benefit in prev. 13–24 months 0.010 0.32 0.021 0.45 0.022 0.46 -0.2%

Unemployment in prev. 12 months 0.066 0.55 0.20 0.93 0.19 0.93 1.0%

Unemployment in prev. 13–24 months 0.20 1.20 0.55 1.91 0.55 1.92 -0.4%

Maternity in prev. 12 months 0.026 0.42 0.028 0.45 0.037 0.51 -1.9%

Maternity in prev. 13–24 months 0.099 0.98 0.11 1.07 0.14 1.19 -2.6%

Total wage in prev. 13–24 months, M HUF 2.05 4.15 1.30 1.60 1.27 1.48 1.8%

Health expenditure history, gender- and age-corrected percentiles

Outpatient, 1 year ago 47.5 30.1 45.1 31.5 45.2 31.0 -0.4%

Outpatient, 2 years ago 47.5 30.0 45.0 31.2 45.0 30.8 0.1%

Inpatient, 1 year ago 9.6 26.7 9.9 27.1 10.2 27.5 -1.3%

Inpatient, 2 years ago 9.6 26.7 9.6 26.7 9.8 27.0 -0.8%

Pharma, 1 year ago 46.7 31.2 43.6 32.2 43.2 32.0 1.2%

Pharma, 2 years ago 46.6 31.3 43.5 32.2 43.1 32.0 1.1%

Days of sick-leave in prev. 13–24 months 3.9 17.0 4.8 19.6 5.3 21.8 -2.3%

Number of observations ∗ 28,169 28,169

∗:No.ofindividuals:1,074,888.No.ofperson-months:38.4−38.9million,dependingonthevariable.Seetext forsamplerestrictions.S.D.:standarddeviation.Standardizeddifference:thedifferenceofmeansdividedbythe squarerootoftheaverageofthetwoindividualvariances.

Fig.1.Ratesofsomebenefitsbygenderandagegroup.

patientcareandinpatientcare,andontheannualpublicplusprivate (out-of-pocket,OOP)expenditureonprescribedpharmaceuticals.Alto- gether,wetrackaround60%oftotalhealthcareexpenditure(basedon theexpenditurecategoriesofGaáletal.,2011).Themostimportantex- cludeditemsareservicesprovidedbyGPs,andOOPpaymentsonnon- prescribedmedicationsandonmedicalservices.AlthoughGPcareis notcoveredbyourdata,totaloutpatientcareexpenditureisreasonably wellcapturedbecauseofthehighusageofoutpatientspecialistcarein Hungary(seeEleketal.,2015).AccordingtoGaáletal.(2011),public expenditureonoutpatientspecialistcareisalmosttwiceasmuchason primarycare,andmadeuparound17%ofspendingoncurativeservices andaround10%oftotalpublichealthcareexpenditureintheexamined period.In2009,thepercapitaannualnumberofoutpatientspecialist contactswas12.0inHungary,thethirdhighestinCentral-andSouth- Eastern-Europe,andhigherthaninanyWestern-Europeancountry.In anycase,sincecontactswithprimarycarephysiciansareneededfor referralstospecialistcareandfortheprovisionofmedicalcertificates fordisability,itisunlikelythatanobserveddisability-relatedincrease ofspecialistcareusewouldbecoupledwithareduceduseofprimary care.

Inadditiontooutpatient,inpatientandpharmaceuticalexpenditure, moredetailedmedicationdatathatprovidepharmaceuticalspendingon the3rdlevelATC(AnatomicalTherapeuticChemical)groupsarealso availableforyears2009−2011for42%oftheindividualsinthesample.3

3 ThismedicationdatasetoriginatesfromNHIFA,andwasprocessedbyCERS.

Thesampleisa50%randomsampleoftheHungarianpopulation,butitwas drawnindependentlyfromthebaselinesampleusedelsewhereinouranalysis.

Sincethebaselineandthemedicationdatadonothavethesame(anonymised) identifiers,weconductaprobabilisticmatchingbetweenthetwodatasets.First, wecreategender– monthlydateofbirth– districtofresidencecellsinboth datasets,withanaveragecellsizeofabout26people.Second,foreachindivid- ualinthebaselinesample,wesearchforapairinthemedicationsamplewho belongstothesamecell,andwhoseoutpatient,inpatientandpharmaceutical expendituresarethemostsimilartothoseinthebaselinedataset.(Theseexpen- ditureitemsareobservedinbothdatasetsfor2009−2011,albeitwithmeasure- menterror,sothereare9matchingvariables.)Similarityisdefinedbymaximis- ingthenumberofequalexpenditureitemsoutofthenon-zeroitemsduringthe threeyears;ifmorethanonepairisfoundthenthesumoftheabsolutediffer- encesofthecorresponding(non-equal)expenditureitemsisminimised;finally, onecandidateisrandomlypickedincaseofadraw.Thematchingisregarded

Forthesepeople,wewillexaminespecificallytheexpenditureoneight main1stlevelATCgroupsthataltogethermakeupmorethan90%of pharmaceuticalspending,andalsodrugcategoriesonthe3rdATClevel forfourmajordiseases(antidepressants,lipidmodifyingagents,antihy- pertensivesandantidiabetics).4

4. Methods

4.1. Treatment– controlcomparisons

Weexaminethemedium-termeffectofinvoluntaryjoblossontaking updisabilitybenefitandonotheroutcomes.Wecomparee.g.disability insuranceenrolmentoflaid-off workerstothosenon-laid-off workers whoweresimilarintheirmeasuredcharacteristicsatthetimeoflay- off.Similarityis defined intermsof thevariablesofTable 1,which includecalendartime,individualdemographiccharacteristics(gender, age,region, settlementtype),characteristicsof thecurrent job(firm size,occupation5),historyoflabourmarket andbenefitstatusin the last24months,historyofhealthexpenditureandsickleaveinthelast twocalendaryears(butnotinthecurrentyear)andthechangeofthe sizeoftheemployee’sfirminthelasttwoyears.

Since we do not observe health status directly, we can only use lagged health expenditure as a proxy for health. Bíró and Elek(2018)showusingthesamedatathathealthexpenditure,inpar- ticularpharmaceuticalexpenditure,isastrongpredictorofmortalityas farassixyearsahead,thuslikelycaptureshealthstatusreasonablywell.

Weincludetheone-andtwo-yearlaggedindicatorsofhealthspend- ingandsickleaveamongthesimilarityvariables.Inprinciple,ifthe masslay-off was precededbyworseningworkenvironment thenthe laggedhealthindicators couldalreadybeaffected. Thiswouldimply thatourestimatedeffectofmasslay-off ondisabilityinsuranceenrol- mentisalowerboundof thetrue effect.Ontheotherhand,thede-

appropriateifthenumberofequal,non-zeroexpenditureitemsislargerthan halfofthenumberofnon-zeroexpenditureitemsofapersoninthebaseline sample.Usingthisprocedure,wefindapairfor42%ofthebaselinesample, whichisclosetothetheoreticalmaximum(50%).

4SeethefootnoteofTable5orFig.5fortheprecisedefinitions.

5Adetailedoccupational(ISCO-based)classificationwith34items,notshown intheTable,isused.

scriptivestatisticsofTable1suggestthattheaveragehealthspending historyofthelaid-off individualsissimilartothatofthewholesample ofworkers,thusthereisnodirectevidencethatamasslay-off wouldbe precededbyincreasedhealthexpenditure.Inanycase,ourstrategyof focusingonmasslay-offshelpstoensurethesimilarityoflaid-off and non-laid-off individualsintermsofhealthstatusbecausemasslay-offs arelesshealth-dependentthanordinarylay-offs.

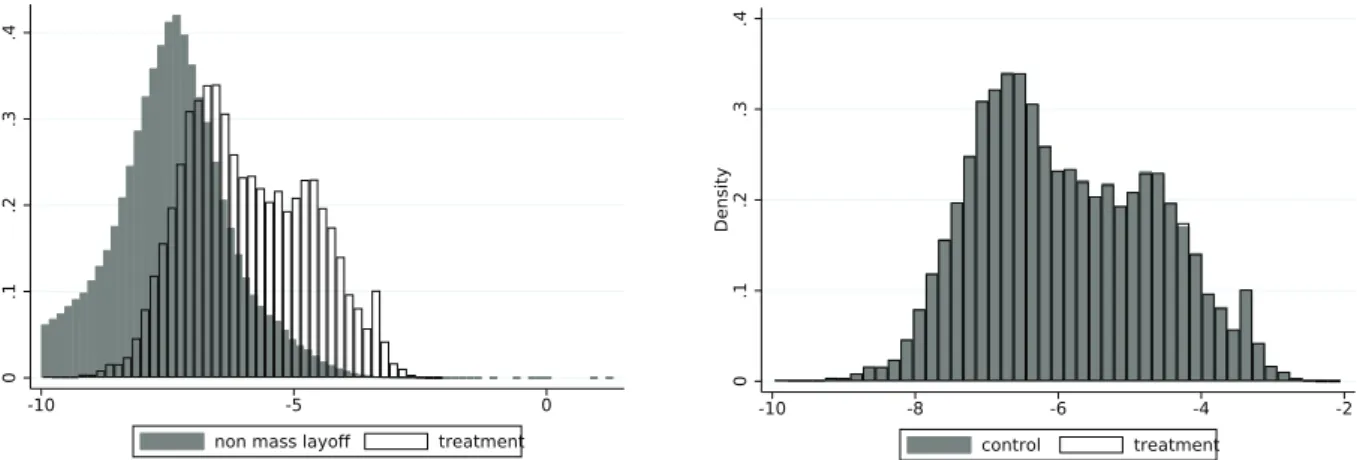

Weperform1:1nearestneighbourpropensityscorematching,ap- plyingalogitmodelwiththeabovesimilarityvariables.6Following,for example,Austin(2011),acaliperof0.2standarddeviationofthelogit scoreisenforcedtoexcludematchesthatarefarfromalaid-off worker intreatmentpropensity.7Exactmatchingisconductedongenderand monthlydate,andmatchingisperformedwithoutreplacementonthe individualbasis.Thatis,ifapersonbelongstothetreatedgrouporis chosenasacontrolobservation,thenshe/hecannotbeinthecontrol groupatanotherdate.However,thecontrolgroupmaycontainindi- vidualswhosefirmsareaffectedbymasslay-off butthemselvesarenot laidoff.

ThelastcolumnofTable1showsthatthelaid-off andthematched controlsample aresufficientlysimilar toeach other withrespect to theexaminedvariables,thestandardizeddifferences8beingbelow7%

(0.07)inallcases,lessthanthe0.10differencetreatedasanappropriate balanceinpropensityscorestudies(e.g.Austin,2009).Fig.A1intheAp- pendixalsoconfirmsthattheestimatedpropensityscoresarebalanced inthetreatment(laid-off)andthematchedcontrolgroup.

Afterfindingasuitablecontrolgroup,weshowgraphicallyhowthe ratioofdisabilitybenefitrecipients,thethree-monthtransitionproba- bilitytodisabilityaswellasotherlabourmarketoutcomesevolveinthe matchedlaid-off vs.controlsamples.Beyondagraphicalanalysis,wees- timatesimplelinearprobabilityandlogitmodelsofsomeoutcomesat 𝑡=24and𝑡=48monthsonthejointsampleofthelaid-off (treatment) andcontrolobservations,withthetreatmentdummyastheexplana- toryvariable.Here𝑡=0denotesthetimeofinclusionintothematched sample(whichisthetimeoflay-off inthetreatmentgroup).Following AbadieandSpiess(2019),intheregressionmodelsweestimatestandard errorsbyclusteringatthelevelofmatchedpairs.Thismethodprovides consistentstandarderrorestimatesifmatchingisdonewithoutreplace- ment,whichholdsinourcase.

Intheregressionmodelsweconcentrateonthreeoutcomevariables.

First,theprobabilitiesofbeingdisabledat𝑡=24andat𝑡=48months areanalysed.Second,toinvestigatewhethergenuinehealthshocksare present,welookatthetwo-andfour-yearmortalityrates.Third,based onthemedicationdataonATCcategories,wecomparetheratesofpeo- pleinthematchedlaid-off vs.controlsampleat𝑡=24and𝑡=48months whoaredisabilityinsurancerecipientsandatthesametimeusespecific drugcategories(i.e.weexaminejointprobabilities).Thisapproachfol- lowsRegeetal.(2009)andprovidesinsightintothetypesofdiseases thatleadtodisabilityinsuranceuptake.Alargerjointprobabilityinthe treatmentvs.thecontrolgroupindicatesthattheadditionaldisability pensionersduetojoblossconsumetheparticularmedicationcategory.

If,ontheotherhand,theratesinthetreatmentandcontrolgroupare similar,thatsuggestsno(orsmall)consumptionofthemedicationcat- egoryamongtheadditionaldisabilityrecipients.

Also,tomeasureheterogeneouslay-off effects, weestimatelinear probabilitymodelsoftheprobabilityofbeingdisabledattwoandfour

6 Usingmorethanonenearestneighbourwoulddecreasethevarianceofthe estimatesatthecostofincreasedbias(CaliendoandKopeinig,2008;Dehejiaand Wahba,2002).However,sincewehavealargesample,eventhe1:1matching yieldsreasonablypreciseestimates.

7 Thisadjustmentaffectsonly4%ofthetreatedsample;henceTable1does notdisplaydescriptivestatisticsseparatelyonthelaid-off andthematchedlaid- off sample.

8 Thestandardizeddifferenceisobtainedbydividingthemeandifferencewith thestandarddeviationofthevariables.Thelatterisapproximatedasthesquare rootoftheaverageofthetwoindividualvariances.

years,respectively,wherethelay-off dummyisinteractedwithindivid- ualcharacteristicssuchasgender,levelofeducation,agegroup,region specificunemploymentrate(measuredat𝑡=0)and– tocapturebase- linehealthstatus– thedummyforhospitalizationinthelastyearbefore 𝑡=0.

4.2. Eventstudyanalyses

Weinvestigate,witheventstudyanalyses,thetimepatternofhealth expenditureofdisplacedworkerswhobecamedisabledsometimeafter thejobloss. Weregress,in afixed-effects setting,theannualhealth expendituremeasuresontheyearselapsedsince(orbefore)theuptake ofdisabilitybenefitwithinthesampleoflaid-off individualsreceiving disabilitybenefit:

ℎ𝑖𝑠=𝜂0+∑

𝑘≠0

𝜂𝑘𝐷(𝑖𝑠𝑘)+𝑐𝑖+𝜉𝑠+𝑢𝑖𝑠, (1)

whereidenotestheindividual,sthecalendartimeinyears,his isan indicatorofhealthexpenditure,𝐷(𝑖𝑠𝑘)(−2≤𝑘≤2)isthetime(inyears) afterorbeforetheuptakeofdisabilitybenefit,𝜉s isthecalendaryear fixedeffect,cicapturesindividualfixedeffects(controllingforalltime- invariantindividualcharacteristicssuchasgenderorinitialhealthsta- tus)anduisdenotestheerrorterm.Theparameters𝜂kareofmaininter- est.

Weusevarioushealthexpenditureindicatorsasoutcomevariables.

First,wesimplyanalysethevaluesofthethreeexpenditurecategories (outpatient,inpatientandprescribedpharmaceuticalexpenditure).Sec- ond,duetothenon-negligiblefractionofzeroexpenditure(i.e.ofnot usingthegivencategoryofhealthcareatallinagivenyear)andtothe highskewnessoftheexpendituredistributions,weanalysetheproba- bilityofpositive(non-zero)healthexpenditureandthelogarithmofthe positive expenditureseparately, inatwo-part(hurdle)modelsetting, forthethree expenditureitems.Thehurdle modelallowsanexplicit distinctionbetweentheextensivemargin(zeroversusnon-zeroexpen- diture)andtheintensivemargin(amountofexpenditureifnon-zero),as widelyusedinhealtheconomics(seeDebandNorton,2018;Pohlmeier andUlrich,1995,amongmanyothers).Finally,weestimateEq.(1)with pharmaceuticalpurchasesbymedication(ATC)categoriesasoutcome variables.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptiveanalysis

Table1displaysdescriptivestatisticsofthegeneralemployedpop- ulation,of workersdisplacedinmasslay-offs, andof workersin the matchedcontrolsample.

AccordingtoTable1,masslay-offspeakedduringthefinancialcrisis in2008–2009,andaffectedmales,thelowereducatedandtheemploy- eesofsmallerfirmsdisproportionatelymoreoften.Furthermore,laid-off workersearnedonethirdlessandspentonemonthlessinemployment, 0.3monthmoreinunemploymentand0.9daymoreonsickleaveinthe 13–24monthsprecedingtheirdisplacementthanthegeneralemployed population.Ontheotherhand,thetwo-yearhealthexpenditurehistory isnotparticularlydifferentinthelaid-off andinthegeneralworking population,asmeasuredbyoutpatient,inpatientandpharmaceutical expenditurepercentiles.Thepercentileswerecalculatedaccordingto the(five-year)agegroup-andgender-specificexpendituredistributions (coveringbothworkersandnon-workers).9

Fig.2displaysthetimepatternofsomelabourforceindicatorsof thematchedlaid-off vs.controlworkers(disabilitybenefitrecipiencyis plottedonFig.3).Thepre-trendsofthetwogroupsareidentical,apart from theseverancepayeffectobserved in monthlywages oflaid-off

9Theaverageinpatientpercentileisaround10forbothgroupsbecauseofthe lowrateofhospitalisation.

Fig.2. Labourforceindicatorsaroundthetimeofmasslay-off.

Fig.3. Disabilitybenefitrecipiencyrates andthree-monthtransitionprobabilitiesin themasslay-off andcontrolgroupsaswell asthetreatment– controldifferences(with 95%confidenceintervals).

workersjustbeforethelay-off.Theemploymentratefallssubstantially atthetimeofmasslay-off andpartlyrevertsafterwards,whiletheun- employmentrateshowstheoppositepattern.Meanwhile,thestockof disabilitybenefitrecipientsincreasesmuchfasterafterthejoblossthan inthecontrolgroup(Fig.3).

5.2. Disabilitybenefits

ThetoprightplotinFig.3showsthatthedifferencebetweenthe disabilitybenefitrecipiencyrateinthemasslay-off andcontrolgroups increasesformorethanfouryearsintheobservationperiod.Table2 displaystheprobabilityofreceivingdisabilitybenefitspecificallyat𝑡= 24and𝑡=48months.Theratioofdisabilitybenefitrecipientsis2.3%

in thelaid-off and1.2%in thecontrolgroupaftertwoyears,hence thedifferenceis1.1%points,whichincreasesto1.4%pointsafterfour years.Inlinewiththesefigures,asimplelogitmodel,containingonly thelay-off dummygivesanoddsratioof1.97aftertwoyearsand1.49 afterfouryears.10 Theaveragemarginaleffectsfromthelogitmodels (notshownhere)arealmostidenticaltothelinearestimates.

Forthesakeofcomparison,weshowinTableB1intheAppendix thatmasslay-off decreasestheprobabilityofemploymentby13−17%

10ThesamplesizeissmallerthanreportedinTable1evenforthetwo-year horizonmodelbecausefuturedisabilitybenefitstatusismissinginsomecases duetoe.g.movingabroadordeath.

Table2

Effectofmasslay-off ontheprobabilityofreceivingdisabilitybenefittwoandfour yearslater.

Probability of receiving disability benefit

at 2 years at 4 years in (matched) control group 0.0121 0.0290 in (matched) laid-off group 0.0236 0.0426

difference (with S.E.) 0.0114 ∗∗∗ (0.0012) 0.0136 ∗∗∗ (0.0023) Logit model odds ratios on receving disability benefit

at 2 years at 4 years coeff. (OR) S.E. coeff. (OR) S.E.

mass lay-off 1.971 ∗∗∗ (0.136) 1.492 ∗∗∗ (0.102) constant 0.012 ∗∗∗ (0.001) 0.030 ∗∗∗ (0.002)

Number of observations 53,114 25,760

Withcluster-robuststandarderrors(S.E.),clusteringatthelevelofmatchedpairs.

∗∗∗p<0.01,∗∗p<0.05,∗p<0.1.

Table3

Linearprobabilitymodelswithcontrolsandinteractionsfortheeffectsofmasslay-off ontheprobabilityofreceivingdisabilitybenefittwoandfouryearslater.

Probability of receiving disability benefit at 2 years at 4 years

coeff. S.E. coeff. S.E.

Interaction of mass lay-off with

male 0.0017 (0.0024) 0.0061 (0.0047)

age group (baseline = 35–39 years)

- 40–44 year 0.0043 ∗ (0.0022) − 0.0034 (0.0046) - 45–49 year 0.0069 ∗∗∗ (0.0026) 0.0052 (0.0055) - 50–54 year 0.0180 ∗∗∗ (0.0033) 0.0288 ∗∗∗ (0.0062) education (baseline = primary)

- lower secondary − 0.0030 (0.0034) 0.0012 (0.0063) - upper secondary 0.0054 (0.0039) 0.0198 ∗∗∗ (0.0075)

- tertiary − 0.0023 (0.0043) 0.0110 (0.0089)

hospitalization in year before 𝑡 = 0 0.0278 ∗∗∗ (0.0062) 0.0225 ∗∗ (0.0105) region specific unemployment rate − 0.0225 (0.0295) 0.0899 (0.1070)

constant 0.0030 (0.0039) − 0.0116 (0.0090)

Main effects (differences in probabilities in the control group)

male 0.0012 (0.0014) − 0.0003 (0.0030)

age group (baseline = 35–39 years)

- 40–44 year 0.0024 ∗ (0.0012) 0.0129 ∗∗∗ (0.0031) - 45–49 year 0.0073 ∗∗∗ (0.0015) 0.0268 ∗∗∗ (0.0036) - 50–54 year 0.0199 ∗∗∗ (0.0019) 0.0390 ∗∗∗ (0.0038) education (baseline = primary)

- lower secondary −0 . 0054 ∗∗∗ (0.0020) −0 . 0129 ∗∗∗ (0.0044) - upper secondary −0 . 0111 ∗∗∗ (0.0021) −0 . 0278 ∗∗∗ (0.0047) - tertiary −0 . 0105 ∗∗∗ (0.0025) −0 . 0261 ∗∗∗ (0.0057) hospitalization in year before 𝑡 = 0 0.0228 ∗∗∗ (0.0035) 0.0365 ∗∗∗ (0.0066) region specific unemployment rate 0.0841 ∗∗∗ (0.0223) 0.1773 ∗∗ (0.0691) year at 𝑡 = 0 (baseline = 2005)

- 2006 −0 . 0059 ∗∗∗ (0.0022) −0 . 0057 ∗∗ (0.0029) - 2007 −0 . 0073 ∗∗∗ (0.0023) −0 . 0111 ∗∗∗ (0.0028)

- 2008 −0 . 0107 ∗∗∗ (0.0020)

- 2009 −0 . 0156 ∗∗∗ (0.0024)

constant 0.0093 ∗∗∗ (0.0027) 0.0135 ∗∗ (0.0060)

Number of observations 53,114 25,760

Cluster-robust standard errors (S.E.), clustering at the levelof matched pairs. ∗∗∗ p<0.01,∗∗p<0.05,∗p<0.1.

points andincreases theprobability of unemployment by3.7−5.3% pointsoverthetwo-andfour-yeartimehorizons,withnosignificant effectonthereceiptofmaternitybenefits.Joblossdecreasesnon-zero earningsby16−17%overthesetimespans,whichisinlinewithother resultsintheliterature(Jacobsonetal.,1993andStevens,1997,among others).

The bottom plots of Fig. 3 show the three-month transition probabilitiestodisabilityandthedifferencesbetweenthelaid-off and thecontrolgroup.The transitionprobabilityjumps highin thelaid- off groupaftertheexpiryofunemploymentbenefit(at6–12months),

whileitincreasesslowlyinthecontrolgroup.Thedifferenceoftransi- tionprobabilitiesisstatisticallysignificantlypositiveinthefirstthree yearsandreacheszeroafterwards.Overall,aroundhalfofthetotalex- cesstransitionsoffouryearsoccurwithinthefirstyear.11

Looking atthelinearprobabilitymodelwithheterogenouseffects inTable3,theinteractiontermsofindividualcharacteristicswithmass

11Comparedtothestockofdisabilitybenefitrecipients,thetransitionrateto theoppositedirectionisnegligible:onlyaround0.6%oftherecipientsreturn toworkandstopreceivingthebenefitinagivenyear.

Table4

Effectofmasslay-off onmortality.

Probability of death

within 2 years within 4 years in (matched) control group 0.0034 0.0049 in (matched) laid-off group 0.0056 0.0085

difference (with S.E.) 0.0022 ∗∗∗ (0.0006) 0.0036 ∗∗∗ (0.0010) Logit model odds ratios of death

within 2 years within 4 years coeff. (OR) S.E. coeff. (OR) S.E.

mass lay-off 1.639 ∗∗∗ (0.213) 1.738 ∗∗∗ (0.267) constant 0.0034 ∗∗∗ (0.0003) 0.0050 ∗∗∗ (0.0006)

Number of observations 56,338 27,344

Withcluster-robuststandarderrors(S.E.),clusteringatthelevelofmatchedpairs.

∗∗∗p<0.01,∗∗p<0.05,∗p<0.1.

Table5

Effectofmasslay-off onthejointprobabilityofdisabilitybenefitrecipiencyandtheusageofspecificmedi- cationcategoriestwoandfouryearslater.

2 years later

ATC A ATC B ATC C ATC J ATC L ATC M

control group 0.0040 0.0024 0.0042 0.0027 0.0007 0.0035

laid-off group 0.0087 0.0058 0.0105 0.0060 0.0007 0.0078

difference 0.0047 ∗∗∗ 0.0034 ∗∗∗ 0.0063 ∗∗∗ 0.0033 ∗∗∗ 0.0000 0.0043 ∗∗∗ (with S.E.) (0.0013) (0.0010) (0.0014) (0.0011) (0.0003) (0.0012) logit OR of lay-off 2.186 ∗∗∗ 2.469 ∗∗∗ 2.522 ∗∗∗ 2.227 ∗∗∗ 1.039 2.236 ∗∗∗ (with S.E.) (0.472) (0.677) (0.517) (0.577) (0.600) (0.514)

anti- lipid mod. anti- anti-

ATC N ATC R depressants agents hypertensives diabetics

control group 0.0038 0.0028 0.0021 0.0020 0.0040 0.0007

laid-off group 0.0072 0.0051 0.0037 0.0057 0.0097 0.0016

difference 0.0034 ∗∗∗ 0.0023 ∗∗ 0.0016 ∗ 0.0037 ∗∗∗ 0.0057 ∗∗∗ 0.0009 ∗ (with S.E.) (0.0012) (0.0010) (0.0009) (0.0010) (0.0013) (0.0006) logit OR of lay-off 1.883 ∗∗∗ 1.926 ∗∗ 1.775 ∗ 2.868 ∗∗∗ 2.449 ∗∗∗ 2.253 ∗ (with S.E.) (0.423) (0.536) (0.544) (0.839) (0.519) (1.113)

Number of observations 15,855

4 years later

ATC A ATC B ATC C ATC J ATC L ATC M

control group 0.0116 0.0096 0.0166 0.0094 0.0026 0.0119

laid-off group 0.0176 0.0142 0.0213 0.0127 0.0021 0.0164

difference 0.0060 ∗∗∗ 0.0047 ∗∗ 0.0047 ∗ 0.0033 ∗ -0.0004 0.0044 ∗∗ (with S.E.) (0.0022) (0.0020) (0.0025) (0.0019) (0.0009) (0.0022) logit OR of lay-off 1.525 ∗∗∗ 1.498 ∗∗ 1.292 ∗ 1.354 ∗ 0.824 1.375 ∗∗ (with S.E.) (0.242) (0.263) (0.178) (0.244) (0.320) (0.220)

anti- lipid mod. anti- anti-

ATC N ATC R depressants agents hypertensives diabetics

control group 0.0119 0.0063 0.0055 0.0090 0.0152 0.0027

laid-off group 0.0165 0.0109 0.0081 0.0100 0.0199 0.0035

difference 0.0046 ∗∗ 0.0046 ∗∗∗ 0.0026 ∗ 0.0010 0.0047 ∗ 0.0008 (with S.E.) (0.0022) (0.0017) (0.0015) (0.0018) (0.0024) (0.0010) logit OR of lay-off 1.390 ∗∗ 1.735 ∗∗∗ 1.485 ∗ 1.109 1.315 ∗ 1.289 (with S.E.) (0.222) (0.363) (0.343) (0.213) (0.189) (0.433)

Number of observations 11,548

Cluster-robuststandarderrors(S.E.),clusteringatthelevelofmatchedpairs

∗∗∗p<0.01,∗∗p<0.05,∗p<0.1.

ATCgroupdefinitions:A– alimentarytractandmetabolism;B– bloodandbloodformingorgans;C– cardiovascularsystem;J– antiinfectivesforsystemicuse;L– antineoplasticandimmunomodulatingagents;

M– musculo-skeletalsystem;N– nervoussystem;R– respiratorysystem.Antidepressants(psychoanaleptics):

N06;lipidmodifyingagentsC10;antihypertensives:C02-C03andC07-C09;antidiabetics:A10.

lay-off showthatjoblossincreasestheprobabilityofreceivingdisability benefitparticularlyamongindividualsaged45–54andamongthosein badhealth,asmeasuredbythedummyforhospitalisationintheyear precedingjobloss.Afteradjustingforthesedifferences,theinteraction termswithgender,educationlevelandmicro-regionalunemployment rate– aproxyforlocallabourmarketconditions– arestatisticallyin- significant.Theseresultsimplythatmasslay-off mightserveasanin- centivetoapplyfordisabilitybenefitamongolderindividualsandthose

inworsehealth.UsingtheterminologyofInderbitzinetal.(2016),the strongereffectofjoblossondisabilitybenefituptakeamongtheolder suggestsacomplementaritybetween(early)retirementanddisability benefits,i.e.thelattermightserveasanoptionforanearlyexitfrom thelabourforce.Itisalsopossiblethatjoblosshasastrongerhealthef- fectonthosewhowereinworsehealthpreviously,leadingtoastronger effectondisabilityenrolment.Weanalysetheunderlyinghealthmech- anismsinthenextsubsections.

Fig.4. EventstudyanalysisofhealthexpenditurearoundtheuptakeofdisabilitybenefitNotes:RegressionestimatesofEq.(1)areplotted.Numberofindividuals:

1,290;numberofperson-years:5,879.95%confidenceintervalsaredisplayed,basedoncluster-robuststandarderrors(clusteringontheindividuallevel).The averageexpenditureonoutpatientcare,inpatientcareanddrugsattime0are56,307and189thousandHUF,respectively.Theaverageusageratesofoutpatient care,inpatientcareanddrugsattime0are0.985,0.658and0.958,respectively.Theaveragelogarithmicvaluesofoutpatient,inpatientanddrugexpenditureat time0are10.66,12.78and11.26,respectively.

ThelowerpanelofTable3displaysthedifferencesofthebaseline, i.e.thenon-laid-off,disablementprobabilitiesbytheexplanatoryvari- ables.Theinteractiontermsshouldbeinterpretedinlightofthefactthat theolder,thelowereducated,thoseinbadhealthandthoselivingin higherunemploymentregionsaremorelikelytotransitiontodisability inthecontrolgroup.Hence,forinstance,locallabourmarketconditions haveanimpactuponthetransitiontodisability,butthisimpactdoes notseemtovarybytreatmentstatus(i.e.bybeinglaid-off ornot).

5.3. Mortalityandtheconsumptionofmedicationcategories

AccordingtoTable4,themortalityrateis0.56%inthelaid-off and 0.34%inthecontrolgroupwithintwoyearsafterthemasslay-off,hence theirdifferenceis0.22%point,whichincreasesto0.36%pointifwe lookatahorizonoffouryears.Inlinewiththesefigures,asimplelogit model,containingonlythelay-off dummygivesanoddsratioof1.64 withintwoyearsand1.74withinfouryears.Thus,ourresultssuggest thatjoblossindeedincreasestheriskofmortality.

Usingtheadditionalmedicationdata, Table5shows therates of peopleinthetreatmentandthecontrolgroupwhoaredisabledand alsoconsumevarioustypesofpharmaceuticalstwoand,respectively, fouryearsafterthelayoff,aswellasthetreatment– controldifferences.

Wealsopresenttheresultsofsimplelogitmodels,containingonlythe lay-off dummyasregressor.Aftertwoyears,theratesaresignificantly andsubstantiallylarger(generallytwiceaslarge)inthetreatmentthan inthecontrolgroupformostpharmaceuticalcategories.Theonlyex-

ceptionis thegroupof antineoplasticandimmunomodulatingagents (L),wheretheestimateddifferenceisessentiallyzero.Comparedtothe controllevel,theconsumptionprobability andoddsinthetreatment groupisparticularlylarge(around2.5-fold)fordrugsofthecardiovas- cularsystem(C),includinglipid-modifyingagentsandantihypertensive medications.Theestimatesarequalitativelysimilarafterfouryears,al- thoughstatisticallysignificantinfewercasesandtherelativeestimated effects(logitoddsratios)aresmaller.Theseresultssuggestthatbeyond physicalhealthshocksasevidencedbythelargermortalityrate,both the diagnosisof chronicphysical conditions(e.g. hypertension, high cholesterollevel,diabetes)andmentalhealthproblems(measuredby theconsumptionofantidepressants)contributetothehigheruptakeof disabilityinsuranceamongthelaid-off.Note,however,thatthefind- ingsshouldbeinterpretedwithsomeprecautionbecausethetreatment andthecontrolgroupareonlybalancedwithrespecttolaggedoverall pharmaceuticalexpenditureandnottolaggedexpenditureonspecific pharmaceuticalcategories,whichisavailableonlyfor2009–2011.

5.4. Healthexpenditure

Togaininsightintothetimepatternofhealthexpenditurearound disabilitybenefituptakeamongindividualswhobecomedisableddue toamasslay-off,Fig.4showstheestimated𝜂kparametersoftheevent studyregressionsofEq.(1).

Accordingtothefigure,allthreeexpenditurecategoriespeakinthe yearwhenindividualsfirstreceivedisabilitybenefit.Theabsolutein-

Fig.5. EventstudyanalysisofcategoriesofpharmaceuticalexpenditurearoundtheuptakeofdisabilitybenefitNotes:RegressionestimatesofEq.(1)areplotted.

95%confidenceintervalsaredisplayed,basedoncluster-robuststandarderrors(clusteringontheindividuallevel).DI:disabilityinsurance.ATCgroupdefinitions:

A– alimentarytractandmetabolism;B– bloodandbloodformingorgans;C– cardiovascularsystem;J– antiinfectivesforsystemicuse;L– antineoplasticand immunomodulatingagents;M– musculo-skeletalsystem;N– nervoussystem;R– respiratorysystem.Antidepressants(psychoanaleptics):N06;lipidmodifying agentsC10;antihypertensives:C02-C03andC07-C09;antidiabetics:A10.

creaseinspendingisthelargestoninpatientcare,followedbyspending ondrugsandthenonoutpatientcare.Overall,inpatientexpenditure increasesfivefold,andtheothertwocategoriesaround2.5-foldinthe twoyearsbefore disabilityinsuranceenrolment.Similarpatternscan beobservedfortheprobabilitiesofnon-zeroexpenditure(thepeakis strongestforinpatientcarewith33%points)andforthelogarithmsof non-zeroexpenditure.Afterclaimingthebenefit,allcategoriesofhealth expenditurestarttodeclinebutdonotreachtheirpre-disabilitylevels.

Fromthepeak,inpatientexpendituredecreasesthemost,whilephar- maceuticalexpendituretheleast.Altogether,theexpenditurecategories remain1.5−2.5timeshigherinthemediumtermcomparedtotwoyears priortoclaimingdisabilitybenefit.

Fig.4reflectsthathealthexpenditurealreadystartstoincrease1−2 yearsbeforedisabilityinsuranceenrolment.Nomatterifgenuinehealth shockslead todisabilityclaimsor thepropensitytoclaim disability benefitsdriveshealthcareuse,thecollectionofmedicalevidenceand theapplicationprocedureitselfrequiretime,whichexplainsthisphe- nomenon.

ThedescriptiveplotspresentedinFig.D3inAppendixDareinline withtheeventstudyregressionestimates.Irrespectivelyofhowmuch timepassedfromthelay-off untiltheuptakeofthedisabilitybenefit,the uptakeisassociatedwithraisedhealthexpenditure,whichdeclinesafter claimingthebenefitbutdoesnotfallbacktoitspre-disabilitylevels.At thesametime,wedonotobserveanoteworthypatternamongthecon- trolpairsofthelaid-off peoplewhobecomelaterdisabled;oramongthe

laid-off butnotdisabledindividuals.Fig.B2inAppendixBalsoshows thatmasslay-off ingeneral(includingnon-disabledlaid-off individuals) hasonlyasmall(negative)effectonhealthspending.

Finally,Fig.5showstheeventstudyestimatesforeight1stlevelATC categoriesandfourwidelyusedmedicationgroups.Roughlyinlinewith theresultsofTable5,thecategoriesonwhichexpendituresignificantly increases1−2yearsbeforedisabilitybenefituptakeandremainsele- vatedafterwardsaredrugsactingonthecardiovascularsystem(C)(in particularlipidmodifyingagentsandantihypertensives),onthenervous system(N)(inparticularantidepressants)andonalimentarytractand metabolism(A)(thatincludeantidiabetics).Changesintheothercate- goriesarenotsignificant.Althoughthiseventstudyanalysisdoesnot allowtheidentificationof thecausalrelationshipbetweenparticular illnessesanddisabilitybenefituptake,itstillprovidesinsightintothe mechanismsthatincreasehealthspendingaroundthetimeofclaiming thebenefit.Overall,itisnotpossibletoidentifyanarrowcategoryof conditionsthatcausethesurgeinhealthexpenditure,butthediagno- sisofchronicphysicalconditions,deteriorationinmentalhealthand physicalhealthshocksmightallbepotentialdrivingfactors.

6. Discussionandconclusions

Usingindividual-leveladministrativepaneldatafromHungary,we analysedtheeffectofjoblossondisabilitybenefituptakeanditsre- lationshipwith health expenditure, particularlywithexpenditure on