JournalofClinicalEpidemiologyxxx(xxxx)xxx

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Reporting quality of trial protocols improved for non-regulated interventions but not regulated interventions: A repeated cross-sectional

study

Szimonetta Lohner

a,b,∗, Dmitry Gryaznov

c, Belinda von Niederhäusern

d,e, Benjamin Speich

c,f, Benjamin Kasenda

c,g,h, Elena Ojeda-Ruiz

c,i, Stefan Schandelmaier

c,j, Dominik Mertz

j,

Ayodele Odutayo

f,k, Yuki Tomonaga

l, Alain Amstutz

c,m,n, Christiane Pauli-Magnus

d, Viktoria Gloy

c, Karin Bischoff

o,p, Katharina Wollmann

o,p, Laura Rehner

o,q,

Joerg J Meerpohl

o,p, Alain Nordmann

c, Katharina Klatte

d, Nilabh Ghosh

r, Ala Taji Heravi

c, Jacqueline Wong

j, Ngai Chow

j, Patrick Jiho Hong

j,s, Kimberly McCord

c,

Sirintip Sricharoenchai

c, Jason W. Busse

j,t, Arnav Agarwal

u,j, Ramon Saccilotto

c, Matthias Schwenkglenks

l,v, Giusi Moffa

c,w, Lars G. Hemkens

c,x,y, Sally Hopewell

f, Erik von

Elm

z, Anette Blümle

A,1, Matthias Briel

c,j,1aCochraneHungary,ClinicalCentreoftheUniversityofPécs,MedicalSchool,UniversityofPécs,Pécs,Hungary

bDepartmentofPublicHealthMedicine,MedicalSchool,UniversityofPécs,Pécs,Hungary

cDepartmentofClinicalResearch,BaselInstituteforClinicalEpidemiologyandBiostatistics,UniversityHospitalBaselandUniversityofBasel,Basel, Switzerland

dDepartmentofClinicalResearch,ClinicalTrialUnit,UniversityHospitalBaselandUniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

eRochePharmaAG,Grenzach-Wyhlen,Germany

fCentreforStatisticsinMedicine,NuffieldDepartmentofOrthopaedics,RheumatologyandMusculoskeletalSciences,UniversityofOxford,Oxford, UnitedKingdom

gDepartmentofMedicalOncology,UniversityHospitalBasel,Basel,Switzerland

hiOMEDICOAG,Research&Development,Freiburg,Germany

iInfantaElenaUniversityHospital,PreventiveMedicineDepartment,Madrid,Spain

jDepartmentofHealthResearchMethods,Evidence,andImpact,McMasterUniversity,Hamilton,Canada

kAppliedHealthResearchCentre,LiKaShingKnowledgeInstituteofStMichael’sHospital,Toronto,Canada

Competing interests: All authors have completedtheUnified Competing Interest form (availableon requestfrom thecorresponding author)and declare: BvN is currently employed by RochePharma AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany. BKis currently employed by iOMEDICO AG, Freiburg, GermanyandreportspersonalfeesfromRoche,Riemser,andAstellas, outsidethesubmittedwork.Allotherauthorsdeclarenofinancialrelationships withanyorganizationthatmighthaveaninterestinthesubmittedworkandnootherrelationshipsoractivitiesthatcouldappeartohaveinfluencedthe submittedwork.

Funding: Thestudywas supportedbytheSwissFederalOfficeofPublicHealth.Thefunder hadnoroleinthestudydesign,datacollectionand analysis, decisionto publish,or preparationof thismanuscript. BSwassupported byan AdvancedPostdoc.Mobilitygrantfrom theSwissNational ScienceFoundation(P300PB_177933).SLwassupportedbytheAlexandervonHumboldtFoundation,GermanyduringherresearchstayattheInstitute for Evidence in Medicine, University ofFreiburg, Germany and iscurrently supported by theJánosBolyai Research Scholarship ofthe Hungarian AcademyofSciencesforSL(BO/00498/17/5). AAreceiveshissalarythroughagrantfromtheMD–PhD programmeoftheSwissNationalScience Foundation(grantnumber323530_177576).

Authors’contributions:AO,SH,EvE,BK,andMBdesignedthemainstudy.SLdesignedthepresentsubstudy.RSdevelopedtheweb-toolfordata extractions.DG,BvN,BS,andMBcoordinateddataextractionfromprotocols. DGperformedstatisticalanalyses. SLandMBwrotethefirstdraftof themanuscript.DG,BvN,BS,BK,EOR,AB,StS,DM,YT,AA,CPM,VG,KB,KKu,LR,SL,JJM,AN,KKl,NG,ATH,JW,NC,PJHH,KMC,SiS, JWB,ArA, MS,LH,SH,EvEand MBwere involvedindatacollection andcritically revisedthemanuscript.Allauthors approvedthefinalversion beforesubmission.

Transparency declaration:MBasthethemanuscript’sguarantoraffirmsthatthemanuscript isanhonest, accurate,and transparentaccountof the studybeingreported;thatnoimportantaspectsofthestudyhavebeenomitted;andthatanydiscrepanciesfromthestudyashavebeenexplained.

Ethicsapprovalandconsenttoparticipate:Allparticipatingethicscommitteeswereprojectpartners.

Patientandpublicinvolvementstatement:Itwasnotappropriatetoinvolvepatientsorthepublicinthedesign,conduct,reporting,ordissemination plansofourresearch.

Disseminationdeclaration:Disseminationofresultstopatientorganisationsisnotapplicable.

1 sharedlastauthorship.

∗Correspondingauthor.faxno.+3672536395;telno.+3672501500 E-mailaddress:lohner.szimonetta@pte.hu(S.Lohner).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.05.011

0895-4356/© 2021TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierInc.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Epidemiology,BiostatisticsandPreventionInstitute,UniversityofZurich,Zurich,Switzerland

mSwissTropicalandPublicHealthInstitute,UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

nDepartmentofInfectiousDiseasesandHospitalEpidemiology,UniversityHospitalBasel,Basel,Switzerland

oInstituteforEvidenceinMedicine,MedicalCenter– UniversityofFreiburg,FacultyofMedicine,UniversityofFreiburg,Freiburg,Germany

pCochraneGermany,CochraneGermanyFoundation,Freiburg,Germany

qDepartmentofEpidemiologyandCommunityHealth,InstituteforCommunityMedicine,UniversityMedicineGreifswald,Greifswald,Germany

rDepartmentofNeurosurgeryandDepartmentofBiomedicine,UniversityHospitalBasel,UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

sDepartmentofAnesthesiologyandPainMedicine,UniversityofToronto,Toronto,Canada

tDepartmentofAnesthesia,McMasterUniversity,Hamilton,Canada

uDepartmentofMedicine,UniversityofToronto,Toronto,ON,Canada

vInstituteofPharmaceuticalMedicine(ECPM),UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

wDepartmentofMathematicsandComputerScience,UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

xMeta-ResearchInnovationCenteratStanford(METRICS),StanfordUniversity,Stanford,USA

yMeta-ResearchInnovationCenterBerlin(METRIC-B),BerlinInstituteofHealth,Berlin,Germany

xCochraneSwitzerland,CentreforPrimaryCareandPublicHealth(Unisanté),UniversityofLausanne,Lausanne,Switzerland

AClinicalTrialsUnit,MedicalCenter– UniversityofFreiburg,FacultyofMedicine,UniversityofFreiburg,Freiburg,Germany Received10February2021;Receivedinrevisedform6May2021;Accepted12May2021;Availableonlinexxx

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the adherence of randomised controlled trial (RCT) protocols evaluating non-regulated interventions (including dietary interventions, surgical procedures, behavioural and lifestyle interventions, and exercise programmes)in comparison withregulatedinterventions tothe StandardProtocolItems:RecommendationsforInterventionalTrials(SPIRIT)2013Statement.

Methods: Weconductedarepeatedcross-sectionalinvestigationinarandomsampleofRCTprotocolsapprovedin2012(n=257) or 2016(n = 292)by researchethics committeesin Switzerland,Germany, or Canada. Weinvestigated the proportionof accurately reportedSPIRIT checklistitemsinprotocolsof trialswithnon-regulatedas comparedtoregulatedinterventions.

Results: Overall, 131 (24%)oftrialprotocols testednon-regulated interventions. In 2012,the medianproportionof SPIRITitems reportedintheseprotocols(59%,interquartilerange[IQR],53%-69%)waslowerthaninprotocolswithregulatedinterventions(median, 74%, IQR, 66%-80%). In 2016, the reporting quality of protocols with non-regulated interventions (median, 75%, IQR, 62%-83%) improvedtothe levelofregulatedinterventionprotocols,whichhad notchangedonaverage.

Conclusions: Reporting of RCT protocols evaluating non-regulated interventions improved between 2012 and 2016, al- though remained suboptimal. SPIRIT recommendations need to be further endorsed by researchers, ethics committees, fund- ing agencies, and journals to optimize reporting of RCT protocols. © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Inc.

Thisisanopen accessarticleunderthe CCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Keywords:Clinicaltrialprotocol;Randomizedcontrolledtrials;Dietaryinterventions;Surgicalprocedures;Behaviouralandlifestyleinterventions;

Reportingguidelines

What is new?

• There was an improvement in adherence of trial protocolsof non-regulatedintervention trialstothe SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommenda- tions for Interventional Trials) recommendations between 2012 and 2016; their reporting quality reached the level of regulated trials in 2016 but still remainedsuboptimal.

• Adescriptivetitle identifyingthe study design,de- tailsondatacollection,plansonaDataMonitoring Committee,access todata,anddetailson ancillary carewere identified as the worst reportedprotocol elementsin non-regulatedtrials in2016.

• The improvements and remaining deficiencies of trial protocols of non-regulated interventions were similar across types of intervention (surgical, di- etary,behavioural, exercise).

1. Introduction

Trials of regulated interventions, such as drugs, bio- logics, or medical devices, must adhere to regulations of responsible authorities (e.g. European Medicines Agency, Swissmedic) [1-4]. Regulators promote completeness and transparency of protocols and prospective registration in atrial register.However,trials assessingnon-regulatedin- terventions, such as dietary interventions, surgical proce-

S.Lohneretal./JournalofClinicalEpidemiologyxxx(xxxx)xxx 3

dures, behavioural and lifestyle interventions, or exercise programmes, are not subject to oversight by regulatory agencies.

Althoughrecommendationshavebeendevelopedforthe design, conduct andreporting of trials withnon-regulated interventions[5,6],studyreports of thesetrials oftenlack importantstudy information,such asfinalsample size[7], age[8],or healthstatusof participants[8],andadherence to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statement isgenerallypoor [8-12].

Careful writing of aclinical trial protocol is important forallinvolvedstakeholders,i.e.researchers,ethicsreview boards,funders, journal editorsandpatients [13], because this document describes the planned research steps and methods in a comprehensive manner. The SPIRIT 2013 Statement(StandardProtocolItems: Recommendationsfor InterventionalTrials),achecklistof aminimalsetofitems tobereportedinaprotocol,wasdevelopedtoimprovethe reporting quality of study protocols [14]. Empirical evi- dence on the impact of the SPIRIT recommendations on the quality of trial protocolswith non-regulated interven- tions is lacking.

The aim of the present study was toassess the extent to which RCT protocols with non-regulated interventions adheredtotheSPIRITrecommendationsin2012and2016, thatis,beforeandaftertheSPIRITrecommendationswere published.Further, we comparedadherencetotheSPIRIT checklist [15] between trial protocols with non-regulated as compared toregulated interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocolselection and inclusion criteria

The present study isoneof the add-on projects of Ad- herencetoSPIritRecommendations-Switzerland,Canada, and Germany (ASPIRE-SCAGE) Study. A detailed de- scription of the methodology,including eligibility criteria, process of protocol selection, data extraction, and addi- tional objectives addressed in add-on studies has previ- ously been published [16]. In brief, the ASPIRE-SCAGE investigated adherence of protocols approved by research ethicscommitteesinSwitzerland,Germany,orCanadabe- fore(2012)andafter (2016)thepublicationofthe SPIRIT guidelines in 2013. Protocols were eligible if they de- scribed an RCT of a health care intervention in patients.

We excluded pilot studies, trials enrolling healthy volun- teers, animalstudies,studiesbased ontissuesamples, and studieswithaquasi-random methodof allocation.Results of ASPIRE-SCAGE will be published separately. Origi- nally, we had planned to additionally include protocols from UK research ethics committees in this subproject, but delaysin accessingprotocols from2016 rendered this not feasible [16].

In the present study we categorised the protocols in- cluded in ASPIRE-SCAGE as follows: 1) drug, 2) bio-

logical, 3) device, 4) dietary supplement, 5) surgery, 6) behavioural,7) exercise, or 8) other non-regulated.

2.2. Dataextraction

From each eligible trial protocol, we extracted main study characteristics and information on the adherence to the SPIRIT checklist [15]. Data extractors assessed whether each item and sub-item of the SPIRIT checklist was reported among eligible trials, either as ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Not applicable’.

Data were extracted by two independent extractors, using web-based software developed for data collection (www.squiekero.org). All extractors signed confidentiality agreementsbeforestartingdataextraction.Toreduceinter- extractor variability in interpreting individual questions, each of the extractors received personaltraining provided byoneoftheprojectleaders(DG,BvN,MB)andextracted the first protocols witha project leader as the second ex- tractor.Thesoftwareenabledcomparisonofextracteddata from two extractors and the discussion of discrepancies before makingaconsensualfinal decision.

2.3. Dataanalysis

WeexpressedadherenceoftrialprotocolstoSPIRITby allocatingascorebetweenzeroandonetoeachof the 33 SPIRITitemsandsummingupthesescores.Eachprotocol was able to reach a total score (hereafter referred to as SPIRITadherencescore)betweenzeroand33points,with higher scores designatingbetter SPIRITadherence[16].

In case of SPIRIT items consisting of a single vari- able,we assigned onepoint if the answer to the question aboutthevariablewas“Yes” or“Notapplicable” andzero pointsif the answer was “No” (dichotomization). In case of composite SPIRIT checklist items with two or more questions(sub-items),weappliedanapproach,whichgave equalcredittoallsub-items(withdichotomizationonsub- item level). The ratio calculated by dividing the number of fulfilled sub-items and the total number of sub-items wasallocatedasascoretothesecomposite SPIRITitems.

Thismeans, for example, that an itemconsisting of three sub-itemsreceived0.66 pointsincasetwosub-items were fulfilled,while onesub-item remained unfulfilled [16].

WecalculatedoveralltrialadherencetoSPIRITfordif- ferent intervention categories (drugs, biologicals, devices, dietarysupplements,surgicalinterventions,behaviouralin- terventionsandexercise)astheproportionofSPIRITitems adhered to per protocol. Adherence to individual SPIRIT checklist items was calculated as the proportion of trial protocols adhering to a given item. In case of composite items – to give equal credit to each of the sub-items – mean proportionswere calculated.

We used descriptive statistical methods to compare characteristics of all intervention categories (drugs, bio- logicals, devices, dietary supplements, surgical interven-

tions, behavioural interventions and exercise). We con- ductedthreemultivariableanalysesusingabetaregression model [17] to examine whether and how the adherence ofregulated andnon-regulated trialprotocolschangedbe- tween 2012 and 2016. The proportion of SPIRIT items adhered toper protocolwas the dependent variable in all three regression analyses. In the first analysis we used all trial protocols from 2012 and included the following independent variables: regulation status, planned sample size, centre status (single vs multiple), sponsorship, re- ported logistic or methodological support from a clinical trial unit (CTU) or contract research organisation (CRO).

In the second analysis we used all protocols from 2016 withthesamesetof independentvariables.Inathirdanal- ysiswe specificallyinvestigated apotentialinteractionbe- tweenyearofapproval(2012or 2016)andregulation sta- tus, by including a corresponding interaction term in the regressionmodel. An additionalmultivariable betaregres- sionanalysiswasrestrictedtonon-regulatedtrialprotocols torevealthefactorsthatpotentiallyinfluencetheadherence of non-regulatedintervention trialprotocols toSPIRIT.

We used R version 3.6.1 for data analysis. We per- formed all statistical testing at the significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

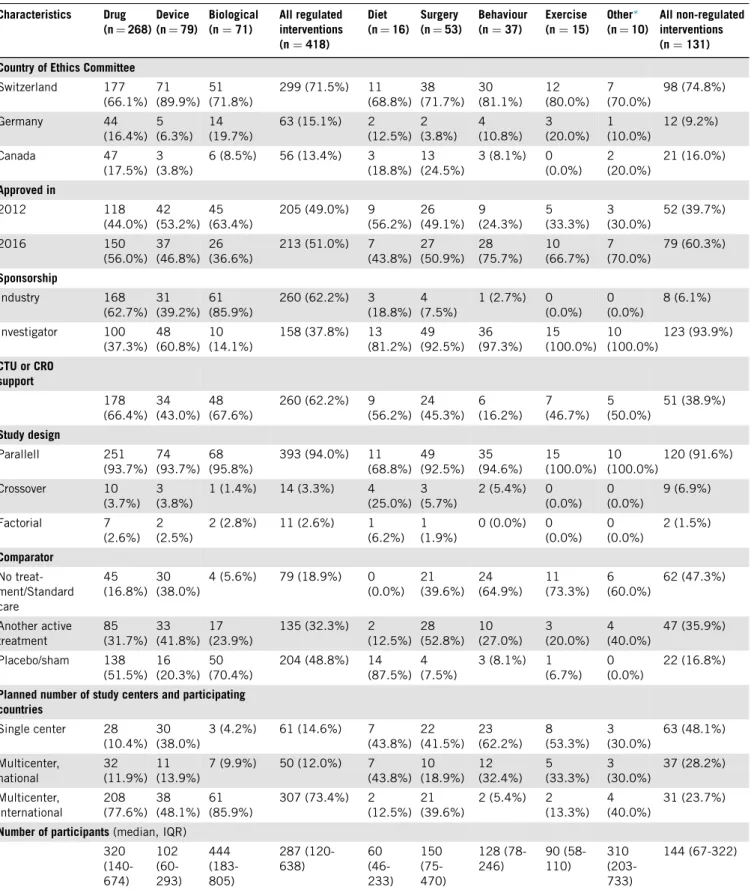

We included 549 trial protocols in our analysis; 257 from 2012 and 292 from 2016. Out of these protocols, 418(76%)describedatrialwitharegulatedand131(24%) atrial with a non-regulated intervention. Wesummarized main characteristics of the included trial protocols inTa- ble1.Non-regulated interventiontrialsmost ofteninvesti- gated surgical procedures (40.5%)or behavioural/lifestyle interventions (28.2%), while protocols with a dietary (12.2%) or exercise intervention (11.5%) were less com- mon in our sample. As the comparator, non-regulated trial protocols most often had no treatment/standard care (47.3%) or another active treatment (35.9%) rather than placebo (16.8%). Most of the non-regulated trial proto- cols reported non-industry sponsorship (93.9%), and sup- portfromaCTU/CROwaslesscommonlymentionedthan inprotocolsof regulatedinterventions (38.9%vs.62.2%).

Plannedsample sizes were lowerfor non-regulated proto- colsthanprotocolsofregulated interventiontrials(median numberof participantswas 144 vs. 287).

Table 2 provides information on the adherence to the SPIRITchecklist for RCTprotocolsofbothregulated and non-regulated interventions.The reporting quality of pro- tocols with regulated interventions had, on average, not changedsubstantiallyfrom 2012to2016 (medianof 74%

versus77%of the SPIRITitemswere adheredtoper pro- tocol,respectively), while we observedfor protocols with non-regulatedinterventionsasubstantialimprovement(me- dianof59%versus75%oftheSPIRITitemswereadhered toperprotocol,in2012and2016,respectively).Wefound

improvements from 2012 to2016 in all non-regulatedin- tervention subcategories with levels of SPIRIT adherence atbaseline rangingfrom 53% to65% (Table 2).

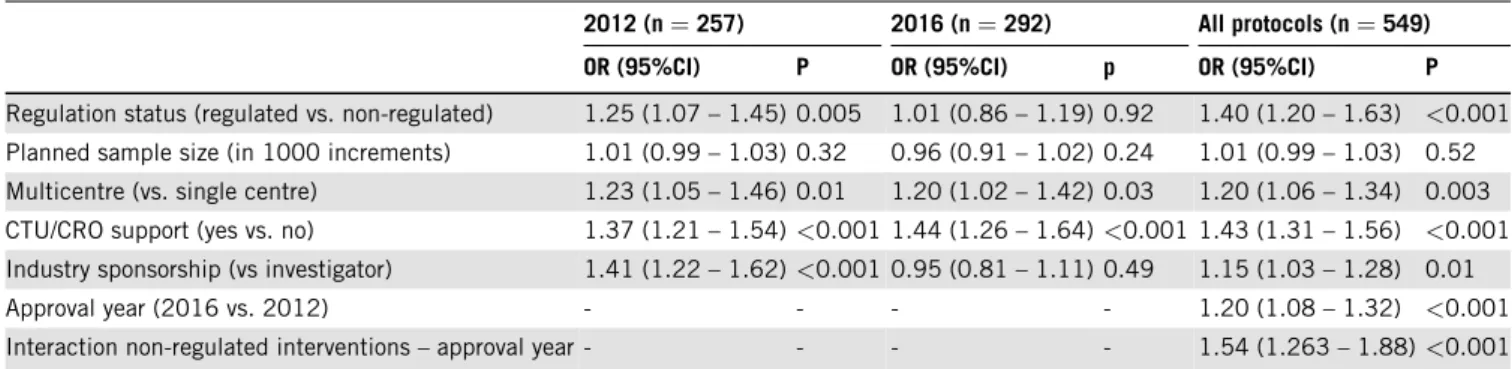

Non-regulated status was identified as an independent predictor of non-adherencein 2012(odds ratio 1.25, 95%

confidence interval 1.07 to 1.45), but not in 2016 (odds ratio 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.86 to 1.19) (Ta- ble 3).This selectiveimprovementof protocols withnon- regulated interventions (subgroup effect) is also reflected inthesignificantinteractiontermbetweeninterventionreg- ulation status and protocol approval year in the third re- gression model inTable 3.

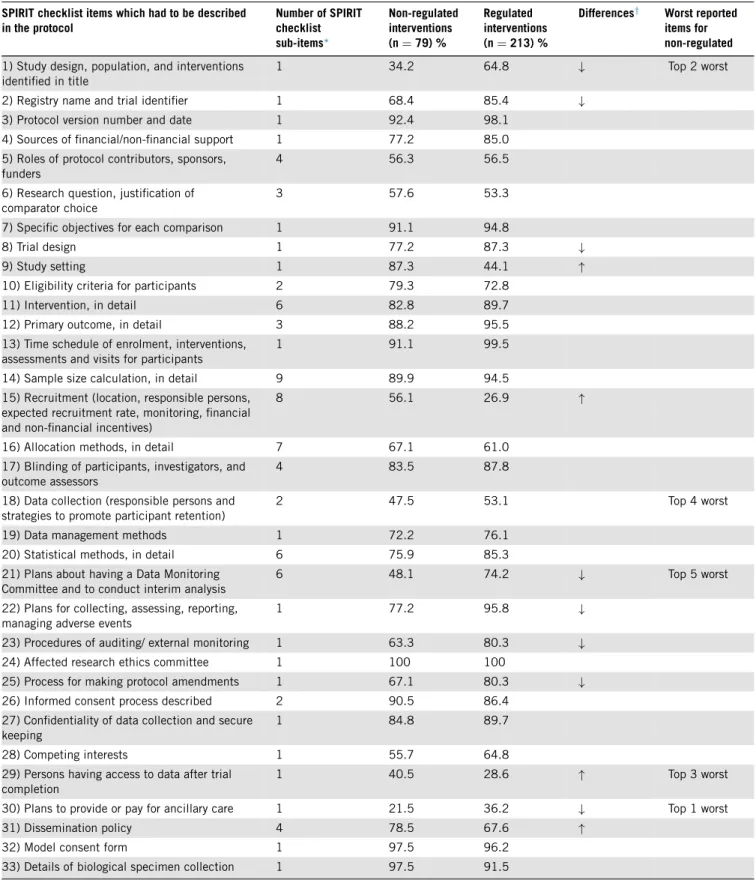

The protocolelements withover 10% difference inthe proportion of SPIRIT adherence between regulated and non-regulatedtrials in2016were: (1)details onstudy de- sign inthetitle, (2)providingtrial registrationdetails, (3) description of trial design, (4) plans about a Data Mon- itoring Committee, (5) monitoring harms, (6) ways for auditing study conduct, (7) process for making protocol amendments, and(8) provisionsfor ancillary care.Details on study setting,recruitment, access to data, and dissem- ination policy were better reported for trials with non- regulated interventions than for the regulated ones (Ta- ble 4). Details on ancillary care,adescriptive title identi- fyingstudydesign,detailsonaccesstodata,datacollection methods,andplansonaDataMonitoringCommitteewere identified as the five least reported SPIRITitems in2016 (Table 4).

Multivariable regression model in protocols evaluating non-regulated interventions showed that more recent ap- proval (2016) and CTU/CRO support were independent predictors of better adherence to SPIRIT, while planned samplesize,thetypeofnon-regulatedintervention(dietary, surgery, behaviour,exercise, other), andbeing amulticen- treorsinglecentrestudy werenot(SupplementaryTable 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary ofprincipal findings

We found an improvement in the completeness of re- porting of protocolsfor trials evaluating non-regulatedin- terventions between 2012 and 2016. Although reporting quality in2016 remained suboptimal, it basically reached the level of protocols of regulated interventions, which did not change over time. We saw this improvement not only overall, but in all investigated subcategories of non- regulated interventions,withthe smallestimprovement for protocols evaluating dietary interventions, and the most pronounced improvement for protocols of exercise pro- grammes.SpecificSPIRITitems withparticularlypoorre- porting (all <50% adherence) were description of study design intitle,detailson datacollection,plansabout hav- ingaDataMonitoringCommittee,detailsonaccesstodata aftertrialcompletion,andplansaboutancillarycare.Apart

S.Lohneretal./JournalofClinicalEpidemiologyxxx(xxxx)xxx 5

Table1.Characteristicsofinvestigatedrandomizedcontrolledtrialprotocols Characteristics Drug

(n=268) Device (n=79)

Biological (n=71)

Allregulated interventions (n=418)

Diet (n=16)

Surgery (n=53)

Behaviour (n=37)

Exercise (n=15)

Other∗ (n=10)

Allnon-regulated interventions (n=131) CountryofEthicsCommittee

Switzerland 177 (66.1%)

71 (89.9%)

51 (71.8%)

299(71.5%) 11 (68.8%)

38 (71.7%)

30 (81.1%)

12 (80.0%)

7 (70.0%)

98(74.8%)

Germany 44

(16.4%) 5 (6.3%)

14 (19.7%)

63(15.1%) 2 (12.5%)

2 (3.8%)

4 (10.8%)

3 (20.0%)

1 (10.0%)

12(9.2%)

Canada 47

(17.5%) 3 (3.8%)

6(8.5%) 56(13.4%) 3 (18.8%)

13 (24.5%)

3(8.1%) 0 (0.0%)

2 (20.0%)

21(16.0%)

Approvedin

2012 118

(44.0%) 42 (53.2%)

45 (63.4%)

205(49.0%) 9 (56.2%)

26 (49.1%)

9 (24.3%)

5 (33.3%)

3 (30.0%)

52(39.7%)

2016 150

(56.0%) 37 (46.8%)

26 (36.6%)

213(51.0%) 7 (43.8%)

27 (50.9%)

28 (75.7%)

10 (66.7%)

7 (70.0%)

79(60.3%)

Sponsorship

Industry 168

(62.7%) 31 (39.2%)

61 (85.9%)

260(62.2%) 3 (18.8%)

4 (7.5%)

1(2.7%) 0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

8(6.1%)

Investigator 100 (37.3%)

48 (60.8%)

10 (14.1%)

158(37.8%) 13 (81.2%)

49 (92.5%)

36 (97.3%)

15 (100.0%)

10 (100.0%)

123(93.9%)

CTUorCRO support

178 (66.4%)

34 (43.0%)

48 (67.6%)

260(62.2%) 9 (56.2%)

24 (45.3%)

6 (16.2%)

7 (46.7%)

5 (50.0%)

51(38.9%)

Studydesign

Parallell 251

(93.7%) 74 (93.7%)

68 (95.8%)

393(94.0%) 11 (68.8%)

49 (92.5%)

35 (94.6%)

15 (100.0%)

10 (100.0%)

120(91.6%)

Crossover 10

(3.7%) 3 (3.8%)

1(1.4%) 14(3.3%) 4 (25.0%)

3 (5.7%)

2(5.4%) 0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

9(6.9%)

Factorial 7

(2.6%) 2 (2.5%)

2(2.8%) 11(2.6%) 1 (6.2%)

1 (1.9%)

0(0.0%) 0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

2(1.5%)

Comparator Notreat- ment/Standard care

45 (16.8%)

30 (38.0%)

4(5.6%) 79(18.9%) 0 (0.0%)

21 (39.6%)

24 (64.9%)

11 (73.3%)

6 (60.0%)

62(47.3%)

Anotheractive treatment

85 (31.7%)

33 (41.8%)

17 (23.9%)

135(32.3%) 2 (12.5%)

28 (52.8%)

10 (27.0%)

3 (20.0%)

4 (40.0%)

47(35.9%)

Placebo/sham 138 (51.5%)

16 (20.3%)

50 (70.4%)

204(48.8%) 14 (87.5%)

4 (7.5%)

3(8.1%) 1 (6.7%)

0 (0.0%)

22(16.8%)

Plannednumberofstudycentersandparticipating countries

Singlecenter 28 (10.4%)

30 (38.0%)

3(4.2%) 61(14.6%) 7 (43.8%)

22 (41.5%)

23 (62.2%)

8 (53.3%)

3 (30.0%)

63(48.1%)

Multicenter, national

32 (11.9%)

11 (13.9%)

7(9.9%) 50(12.0%) 7 (43.8%)

10 (18.9%)

12 (32.4%)

5 (33.3%)

3 (30.0%)

37(28.2%)

Multicenter, international

208 (77.6%)

38 (48.1%)

61 (85.9%)

307(73.4%) 2 (12.5%)

21 (39.6%)

2(5.4%) 2 (13.3%)

4 (40.0%)

31(23.7%)

Numberofparticipants(median,IQR) 320

(140- 674)

102 (60- 293)

444 (183- 805)

287(120- 638)

60 (46- 233)

150 (75- 470)

128(78- 246)

90(58- 110)

310 (203- 733)

144(67-322)

Abbreviations:CTU,clinicaltrialsunit;CRO,contractresearchorganisation;IQR,interquartilerange.

Whennotindicatedotherwise,dataareexpressedastotalnumber(percentagewithinthecorrespondinggroup).

∗Othertrialprotocolsthatincludedanytypeofnon-regulatedintervention,whichwewerenotabletoclassifytothefourpre-definednon- regulatedcategories(e.g.interventionwithageriatricevaluationtool;intermittentvs.continuousoxygensaturationmonitoring;coldexposurevs.

roomtemperature).

Table2.OverallprotocoladherencetoSPIRITaccordingtointerventioncategory Yearof

approval

Drug (n=268)

Device (n=79)

Biological (n=71)

Allregulated interventions (n=418)

Diet (n=16)

Surgery (n=53)

Behaviour (n=37)

Exercise (n=15)

Other‡ (n=10)

All

non-regulated interventions (n=131) 2012 SPIRIT

adher- ence scores median (IQR)∗

24.5 (22.8- 26.2)

21.83 (18.9- 25.1)

25.2 (23.8- 26.9)

24.4(21.9- 26.3)

21.5 (19.0- 25.3)

19.6 (17.8- 23.0)

18.8 (15.9- 20.5)

18.3 (16.5- 19.5)

17.3 (14.8- 20.8)

19.4(17.5- 22.9)

Median% (IQR)†

74 (69-79)

66 (57-76)

76 (72-82)

74(66-80) 65 (58-77)

60 (54-70)

57 (48-62)

56 (50-59)

53 (45-63)

59(53-69)

2016 SPIRIT adher- ence scores, median (IQR)

25.3 (23.4- 27.1)

23.9 (21.2- 26.3)

25.8 (23.6- 26.6)

25.3(23.0- 27.0)

22.5 (15.5- 26.1)

24.5 (20.2- 26.8)

25.5 (22.3- 27.5)

26.6 (22.3- 271)

24.08 (21.8- 28.5)

24.6(20.5- 27.3)

Median% (IQR)

77 (71-82)

72 (64-80)

78 (72-81)

77(70-82) 68 (47-79)

74 (61-81)

77 (68-84)

81 (68-83)

73 (66-87)

75(62-83)

Abbreviation:IQR,interquartilerange.

∗Spiritadherence scoresare expressedas median(IQR)foreachinterventioncategory. Eachsingleprotocolwasable toreachaSPIRIT adherencescorebetweenzeroand33points(i.e.weallocatedascorebetweenzeroandoneforeachofthe33SPIRITchecklistitems),with higherscoresindicatinggreaterSPIRITadherence.

†%meansthemedianpercentofSPIRITitemsthatwereadheredtoperprotocol.

‡Othertrialprotocolsthatincludedanytypeofnon-regulatedintervention,whichwewerenotabletoclassifytothefourpre-definednon- regulatedcategories(e.g.interventionwithageriatricevaluationtool;intermittentvs.continuousoxygensaturationmonitoring;coldexposurevs.

roomtemperature).

Table3.Multivariableregressionanalysesfortheyears2012,2016andforallincludedstudyprotocolsforpotentialpredictorsofSPIRITadherence 2012(n=257) 2016(n=292) Allprotocols(n=549)

OR(95%CI) P OR(95%CI) p OR(95%CI) P

Regulationstatus(regulatedvs.non-regulated) 1.25(1.07– 1.45)0.005 1.01(0.86– 1.19)0.92 1.40(1.20– 1.63) <0.001 Plannedsamplesize(in1000increments) 1.01(0.99– 1.03)0.32 0.96(0.91– 1.02)0.24 1.01(0.99– 1.03) 0.52 Multicentre(vs.singlecentre) 1.23(1.05– 1.46)0.01 1.20(1.02– 1.42)0.03 1.20(1.06– 1.34) 0.003 CTU/CROsupport(yesvs.no) 1.37(1.21– 1.54)<0.0011.44(1.26– 1.64)<0.0011.43(1.31– 1.56) <0.001 Industrysponsorship(vsinvestigator) 1.41(1.22– 1.62)<0.0010.95(0.81– 1.11)0.49 1.15(1.03– 1.28) 0.01

Approvalyear(2016vs.2012) - - - - 1.20(1.08– 1.32) <0.001

Interactionnon-regulatedinterventions– approvalyear- - - - 1.54(1.263– 1.88)<0.001 Abbreviations:CI,confidenceinterval;CRO,contractresearchorganisation;CTU,clinicaltrialsunit;OR,oddsratio.

fromtheapprovalyear, reportedCTU/CROsupportinthe protocol was an independent predictor of better protocol reportingqualityintrialswithnon-regulatedinterventions.

Adherence was worse than in regulated trials for report- ing the study design in the title, trial registration details, study design, plans about a Data Monitoring Committee, about collecting details on harms, about auditing, about the process for making protocol amendments, and about provideor payforancillary care.Reportingwasbetterfor details on study setting, recruitment, access to data, and disseminationpolicy.

4.2.Strengths and weaknesses ofthe study

Strengths of ourstudy includefull access toRCT pro- tocolsandtheirassociateddocumentsfromresearchethics

committeesinthreecountries.IncludedRCTsconsistofall or arandomsample of approved protocolsata participat- ing research ethics committee. During data extraction we followedarigorousprocesswithpilot-testingofextraction forms and calibration exercises among all data extractors participatinginthe projecttominimize inter-extractordif- ferences. More than 95% of included protocols approved in2012andover80%ofprotocolsapprovedin2016were extractedandassessed bytwo independent reviewers.

It was a limitation of our study that, whereas all re- search ethic committees from Switzerland participated, only aconvenience sample of one ethics committee from Germany(Freiburg)andonefromCanada(Hamilton)took part. Thereby, Swiss protocols are overrepresented in our sample and we could not conduct meaningful sub-group analysesaccording to country. Accordingly, we cannot be

S.Lohneretal./JournalofClinicalEpidemiologyxxx(xxxx)xxx 7

Table4.AdherencetoindividualSPIRITchecklistitemsin2016 SPIRITchecklistitemswhichhadtobedescribed

intheprotocol

NumberofSPIRIT checklist sub-items∗

Non-regulated interventions (n=79)%

Regulated interventions (n=213)%

Differences† Worstreported itemsfor non-regulated 1)Studydesign,population,andinterventions

identifiedintitle

1 34.2 64.8 ↓ Top2worst

2)Registrynameandtrialidentifier 1 68.4 85.4 ↓

3)Protocolversionnumberanddate 1 92.4 98.1

4)Sourcesoffinancial/non-financialsupport 1 77.2 85.0 5)Rolesofprotocolcontributors,sponsors,

funders

4 56.3 56.5

6)Researchquestion,justificationof comparatorchoice

3 57.6 53.3

7)Specificobjectivesforeachcomparison 1 91.1 94.8

8)Trialdesign 1 77.2 87.3 ↓

9)Studysetting 1 87.3 44.1 ↑

10)Eligibilitycriteriaforparticipants 2 79.3 72.8

11)Intervention,indetail 6 82.8 89.7

12)Primaryoutcome,indetail 3 88.2 95.5

13)Timescheduleofenrolment,interventions, assessmentsandvisitsforparticipants

1 91.1 99.5

14)Samplesizecalculation,indetail 9 89.9 94.5

15)Recruitment(location,responsiblepersons, expectedrecruitmentrate,monitoring,financial andnon-financialincentives)

8 56.1 26.9 ↑

16)Allocationmethods,indetail 7 67.1 61.0

17)Blindingofparticipants,investigators,and outcomeassessors

4 83.5 87.8

18)Datacollection(responsiblepersonsand strategiestopromoteparticipantretention)

2 47.5 53.1 Top4worst

19)Datamanagementmethods 1 72.2 76.1

20)Statisticalmethods,indetail 6 75.9 85.3

21)PlansabouthavingaDataMonitoring Committeeandtoconductinterimanalysis

6 48.1 74.2 ↓ Top5worst

22)Plansforcollecting,assessing,reporting, managingadverseevents

1 77.2 95.8 ↓

23)Proceduresofauditing/externalmonitoring 1 63.3 80.3 ↓

24)Affectedresearchethicscommittee 1 100 100

25)Processformakingprotocolamendments 1 67.1 80.3 ↓

26)Informedconsentprocessdescribed 2 90.5 86.4

27)Confidentialityofdatacollectionandsecure keeping

1 84.8 89.7

28)Competinginterests 1 55.7 64.8

29)Personshavingaccesstodataaftertrial completion

1 40.5 28.6 ↑ Top3worst

30)Planstoprovideorpayforancillarycare 1 21.5 36.2 ↓ Top1worst

31)Disseminationpolicy 4 78.5 67.6 ↑

32)Modelconsentform 1 97.5 96.2

33)Detailsofbiologicalspecimencollection 1 97.5 91.5

∗Foritemswithmorethanonesub-item,themeanproportionofprotocolsadheringtothesub-itemsofthegivenSPIRITitem(%)wascalculated

† ↓indicatesSPIRITitemswhereadherencewas≥10%worseincaseofnon-regulatedascomparedtoregulatedinterventions,while↑indicates thatadherencefornon-regulatedinterventionprotocolswas≥10%betterthanforregulatedprotocols;Top1-5worstindicatethosefiveSPIRIT items,whichnon-regulatedprotocolswerelesslikelytoadhereto.