ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Neuroscience Research

j ou rn a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / n e u r e s

Review article

Oscillotherapeutics – Time-targeted interventions in epilepsy and beyond

Yuichi Takeuchi

a,b,∗, Antal Berényi

a,c,d,∗aMTA-SZTE‘Momentum’OscillatoryNeuronalNetworksResearchGroup,DepartmentofPhysiology,UniversityofSzeged,Szeged,6720,Hungary

bDepartmentofNeuropharmacology,GraduateSchoolofPharmaceuticalSciences,NagoyaCityUniversity,Nagoya,467-8603,Japan

cHCEMM-SZTEMagnetotherapeuticsResearchGroup,UniversityofSzeged,Szeged,6720,Hungary

dNeuroscienceInstitute,NewYorkUniversity,NewYork,NY10016,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received27November2019 Receivedinrevisedform 18December2019 Accepted19December2019 Availableonline16January2020

Keywords:

Oscillation

Closed-loopintervention Transcranialelectricalstimulation Neuromodulation

Epilepsy

Psychiatricdisorders Oscillopathy Oscillotherapeutics

a b s t r a c t

Oscillatorybrainactivitiessupportmanyphysiologicalfunctionsfrommotorcontroltocognition.Disrup- tionsofthenormaloscillatorybrainactivitiesarecommonlyobservedinneurologicalandpsychiatric disordersincludingepilepsy,Parkinson’sdisease,Alzheimer’sdisease,schizophrenia,anxiety/trauma- relateddisorders,majordepressivedisorders,anddrugaddiction.Therefore,thesedisorderscanbe consideredascommonoscillationdefectsdespitehavingdistinctbehavioralmanifestationsandgenetic causes.Recenttechnicaladvancesofneuronalactivityrecordingandanalysishaveallowedustostudy thepathologicaloscillationsofeachdisorderasapossiblebiomarkerofsymptoms.Furthermore,recent advancesinbrainstimulationtechnologiesenabletime-andspace-targetedinterventionsofthepatho- logicaloscillations ofboth neurologicaldisorders and psychiatricdisorders aspossible targetsfor regulatingtheirsymptoms.

©2020PublishedbyElsevierB.V.

Contents

1. Introduction:oscillationsandneuronalactivitiesareself-organized...88

2. Oscillopathy–aphenomenologicaloverview ... 89

2.1. Epilepsy ... 89

2.2. Parkinson’sdisease...89

2.3. Alzheimer’sdisease...89

2.4. Schizophrenia...90

Abbreviations:6-OHDA,6-hydroxydopamine;AI,artificialintelligence;AD,Alzheimer’sdisease;AMY,amygdala;BDNF,brain-derivedneurotrophicfactor;CSFA,cross- spectralfactoranalysis;CSTC,corticostriatal-thalamocortical;DBS,deepbrainstimulation;DLPFC,dorsolateralprefrontalcortex;DMN,defaultmodenetwork;DSM-5, diagnosticandstatisticalmanualofmentaldisorders;DSP,digitalsignalprocessor;DRT,dopaminereplacementtherapy;ECN,executivecontrolnetwork;ECoG,elec- trocorticography;ECT,electroconvulsivetherapy;EEG,electroencephalography;FDA,foodanddrugadministration;fMRI,functionalmagneticresonanceimaging;FPGA, field-programmablegatearray;GAD,generalizedanxietydisorder;GPU,graphicalprocessingunit;HD-tACS,highdefinitiontranscranialalternatingcurrentstimulation;

HD-tDCS,highdefinitiontranscranialdirectcurrentstimulation;HPC,hippocampus;ICA,independentcomponentanalysis;IoT,internetofthings;ISP,intersectional- shortpulse;LFP,localfieldpotential;MAM,methylazoxymethanolacetate;MDD,majordepressivedisorder;MEG,magnetoencephalography;MS,medialseptum;MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine;NAc,nucleusaccumbens;PCA,principalcomponentanalysis;PCP,phencyclidine;PD,Parkinson’sdisease;PFC,prefrontal cortex;PTSD,posttraumaticstressdisorders;PTZ,pentylenetetrazole;PV,parvalbumine;REM,rapideyemovement;rTMS,repetitivetranscranialmagneticstimulation;SNc, substantianigraparscompacta;STN,subthalamicnucleus;SUDEP,suddenunexpecteddeathinepilepsy;tACS,transcranialalternatingcurrentstimulation;tDCS,transcranial directcurrentstimulation;TES,transcranialelectricalstimulation;tFUS,transcranialfocusedultrasoundstimulation;TI,temporalinterference;TMS,transcranialmagnetic stimulation.

∗Correspondingauthorsat:MTA-SZTE‘Momentum’OscillatoryNeuronalNetworksResearchGroup,DepartmentofPhysiology,UniversityofSzeged,Szeged,10Domsqr., 6720,Hungary.

E-mailaddresses:yuichi-takeuchi@umin.net(Y.Takeuchi),drberenyi@gmail.com(A.Berényi).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2020.01.002 0168-0102/©2020PublishedbyElsevierB.V.

2.5. Anxietyandtrauma-relateddisorders...90

2.6. Majordepressivedisorder...90

2.7. Drugaddiction ... 91

3. Mappingofoscillopathies...91

3.1. Animalmodels...91

3.1.1. Animalmodelsforepilepsy...91

3.1.2. AnimalmodelsforParkinson’sdisease...92

3.1.3. AnimalmodelsforAlzheimer’sdisease...92

3.1.4. Animalmodelsforschizophrenia...92

3.1.5. Animalmodelsforanxietyandtrauma-relateddisorders...93

3.1.6. Animalmodelsfordepressivedisorders...93

3.1.7. Animalmodelsfordrugaddiction...94

3.2. Neuralactivityrecordings...94

3.2.1. Foranimalresearch...94

3.2.2. Forclinicalpractice...94

3.3. Machinelearning-mediatedapproachesforanalysis...94

4. Oscillopathy–therealisticviewofpathologicaloscillatorystatesandastrategyforoscillotherapeutics...95

4.1. Bistableormultistablecircuitstates...95

4.1.1. Modellingconceptandexampleofseizuremodel ... 95

4.1.2. Generationofhypothesisandquantificationofcircuitstates...95

4.2. Stimulationstrategies...95

4.2.1. Open-loopinterventions...95

4.2.2. Closed-loopinterventions...95

4.2.3. Howtoeffectivelyintroduceordisturboscillatoryactivities...97

5. Oscillotherapeutics–embodimentfordistinctmodalities...97

5.1. Deepbrainstimulation...97

5.2. Transcranialelectricalstimulationtechnologies...97

5.2.1. Highdefinitiontranscranialdirectcurrentstimulation...98

5.2.2. Highdefinitiontranscranialalternatingcurrentstimulation...98

5.2.3. Temporalinterferencestimulation ... 98

5.2.4. Intersectionalshortpulsestimulation...99

5.3. Transcranialmagneticstimulation ... 99

5.4. Transcranialfocusedultrasonicstimulation...99

5.5. Optogenetics...99

6. Engineeringchallengesandfuturedirections...101

6.1. Recordingandrealtimeprocessingofpathologicaloscillations ... 101

6.2. Stimulation:preciselocalizationfortargetingaseizure(orsymptom)focusinthebrain...101

6.3. Deviceimplementation-miniaturization,powersupply,andIoTinthe5Gera...102

AuthorContributions...102

Acknowledgments...102

References...102

1. Introduction:oscillationsandneuronalactivitiesare self-organized

Incontextsoftheneurosciencefield,oscillationsarerhythmic neuronalactivities(Buzsáki,2006).Theyaretypicallymeasured asfluctuatingextracellularpotentialsbyusingelectroencephalog- raphy(EEG),electrocorticography(ECoG), intracraniallocalfield potential(LFP)or read outwithfunctional brainimaging tech- niquesormagnetoencephalography(MEG)eachofferingdifferent timeandspatialresolutions(HongandLieber,2019).Themajor source of oscillations is rhythmically synchronizing synaptic transmissions. The rhythmicity stems from network structures composedofdistinctcell-typesandthepopulationactivitiesinside thenetwork (Buzsákiet al.,2012).For example, at mesoscopic networklevels,inhibitoryneuronsareessentialtogenerateoscil- latorynetworkactivities;theinteractionsofexcitatorypyramidal and inhibitory basket neurons via their reciprocal connections generategammabandoscillationsandsharpwave-ripplesinthe hippocampus(HPC)(BuzsákiandWatson,2012;Starketal.,2014).

At macroscopic network levels (the interaction between brain regions),themedialseptum(MS,arhythmogenicbasalforebrain nucleus)externallyregulatesthetabandoscillationsintheHPC (Kangetal.,2017).Emergentoscillations(theextracellularelectri- calfield)thenorchestratesneuronalactivities(theephapticeffects)

(Anastassiouetal.,2011).Thus,oscillationsandneuronalactivi- tiesinthebrainareinterdependentandself-organized.Oscillations reflectfunctionalnetworkstates,andtheyaffectneuronalpopula- tionactivitiesinthenetwork.

Manystudieshaverevealedthatoscillatorybrainactivitiessup- portvariousbrainfunctionssuchasmotorcontrolandcognition includingspatialmemory(Girardeauetal.,2009),arbitraryrep- resentationalspaces(Agarwaletal.,2014;Solomonetal.,2019), sleep(Watsonand Buzsáki,2015), and emotions(Karalis etal., 2016;Likhtiketal.,2014)viatemporallycoordinatedinteractions betweenmultiplebrainregions(Bonnefondetal.,2017).Therefore, ifoscillationsaredisrupted(andtheneuronalactivityisconse- quently disrupted), normal brain functionsare supposed tobe disrupted.Ifoscillationsreflectbothnormalandpathologicalbrain states,theycouldbegoodbiomarkersofsymptomsorbehavioral phenotypesofneurologicalandpsychiatricdisorders.Oscillations arethedynamicsofmacroscopicneuronalcircuits,whichisthe closestto thebehavioural phenotypesin themultiple levelsof biologicalstructure(Fig.1)(Leuchteretal.,2015).Thus,itisnot surprisingthatmore-and-morestudiesshowthecoincidenceof thetemporalexpressionofpathologicaloscillationswiththatofthe abnormalbehavioralphenotypesofneurologicalandpsychological disorders(seeSection2);thesedisordersareconsideredas‘Oscil- lopathies’(Mathalon and Sohal, 2015). Pathological oscillations

Fig.1. Theconceptofoscillotherapeutics.

Abehaviorisgeneratedasaresultofbraindynamics.Braindynamicsaredeter- minedbyfactorsatvariouslevelsfromgenestomacroscopicnetworkactivityasa hierarchicalsystem.Themacroscopiccircuitlevelistheclosesttothebehaviorlevel.

Therefore,oscillation(whichreflectsthedynamicsofthemacroscopiccircuitlevel) supposestohaveaclosetemporalcorrelationto(andanevidentcausalrelationship to)behavioralphenotypes.Therearehugevariationsatboththegeneandsubcel- lularlevelsofneurologicalandpsychiatricdisorders.Incontrast,variationsinthe phenomenologyofneurologicalandpsychiatricdisordersatthemacroscopiccircuit level(oscillation)arerelativelyminor.Therefore,time-targetedpathologicaloscil- lationinterventionforneurologicalandpsychiatricdisorders(oscillotherapeutics) couldbeaneffectivestrategyforregulatingtheirbehavioralphenotypes.

possiblycomewithboth acorrelationanda causalrelationship withabnormalbrainstatesandfunctions.Ifthisisthecase,the pathologicaloscillationsmaybeatherapeuticinterventionormod- ulationtargetforthedisordersusingtherecentlyemergedtime- andspace-targetedbrainstimulationtechnologies(Berényietal., 2012;Vöröslakosetal.,2018).Wecallthisstrategy‘Oscillothera- peutics’.

In the following sections, we provide overviews on 1) the phenomenologyofoscillopathies,2)howwefindabnormalityin oscillationsinanimalmodelsandhumansubjects,3)howpatho- logicaloscillatorystates emergemechanically,a strategy forits intervention,4)theembodimentsofoscillotherapeuticsindistinct stimulationmodalities,and5)theengineeringchallengesoffuture clinicalapplicationsofoscillotherapeutics.

2. Oscillopathy–aphenomenologicaloverview

Oscillopathyisdefinedasaneurologicalorpsychiatricdisor- derinwhichabnormalityinoscillatorybrainactivitiesisobserved (Braunetal.,2018;BuzsákiandWatson,2012;MathalonandSohal, 2015).Wewillbrieflysummarizeabnormaloscillationsofknown oscillopathieswhichcanbetargetedbyinterventions.

2.1. Epilepsy

Epilepsyisaneurologicaldisordercharacterizedbyanenduring predispositiontogenerateepilepticseizures(Fisheretal.,2014).

Anepilepticseizureis atransientbehavioralchangethatmight carryobjective,overtsigns(e.g.convulsions)orsubjective,covert symptoms (e.g.loss of consciousness).These changes aremost probablycaused byabnormallysynchronousneuronalactivities inthebrain.Thesynchronizedneuronalactivityisquiteevident inEEGmeasurementsduringseizures(ictalperiod)andtheEEG synchronizationisconcomitantwithbehaviouralmanifestations suchas tonicandclonicconvulsions.Successfulpharmaceutical andsurgicaltreatments ofepilepsyconsistentlyreducethefre- quencyofelectrographicandbehaviouralseizures(Glauseretal., 2006;Liand Cook,2018).Furthermore,time-targetedinterven-

tion with the pathological neuronal oscillations of seizures or seizurepredictionssuppressesthebehaviouralmanifestation of seizures(Morrell,2011).Thisstronglysuggestsacausalrelation- shipbetweenthepathologicaloscillationofEEGmeasurementsand thesymptomsofepilepsy.Thus,epilepsyisatypicaloscillopathy.

2.2. Parkinson’sdisease

Parkinson’sdisease(PD)isaneurodegenerativediseasecharac- terizedbytremor,rigidity,bradykinesia,andposturalinstability withthe underlyingloss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons (Soileau and Chou, 2016). The pathological hallmark of PD is thefindingofproteinaggregatescontaining␣-synucleininneu- ronscalledLewy bodiesthroughout brain.SymptomsofPDare thoughtto becaused by the dysfunctionof the corticostriatal- thalamocortical(CSTC)loopduetodecreaseddopaminergictone.

Dopaminereplacementtherapy(DRT)istypicallyusedtoame- lioratetheassociatedmotordisturbances.Therearepathological oscillationsoftremor(4–7Hz),doubletremor(10Hz),andbeta (15–30Hz)frequenciesintheCSTCloopofPDpatients(Holtetal., 2019;Weinbergeretal.,2009)andanimalmodels(Deffainsand Bergman,2019; Heimeretal.,2006).Disruption ofpathological oscillationsbyDRT(Heimeretal.,2006),theinactivationofthe subthalamicnucleus(STN)(Wichmannetal.,1994),ordeepbrain stimulation(DBS) oftheSTN(Deuschletal., 2006)consistently decreasesthemotordisturbancesofPD.Thissuggestsacausalrela- tionshipbetweenthepathological oscillationsandsymptomsof PD(Bergmanetal.,2015).ThetargetoftheSTNstimulationmay bethecorticostriatalaxons(Gradinaruetal.,2009).Theintrinsic, slowlyoscillatingrestingnetworkactivity,measurablebyfMRI,is calleddefaultmodenetwork(DMN)(Raichle,2015).Thisnetwork mostlyconsistsofhub-likebrainstructuresincludingthemedial prefrontalcortex(PFC),theprecuneus,andtheposteriorcingulate cortex(Hagmannetal.,2008).InPDpatients,therearePDspe- cificchangesintheDMN(Delaveauetal.,2010;vanEimerenetal., 2009).ThesechangeswererestoredbyDRT(Delaveauetal.,2010) andpossiblywillalsoberestoredbyDBSinthefuture(Kringelbach etal.,2011).

2.3. Alzheimer’sdisease

Alzheimer’sdisease(AD) isa chronicneurodegenerative dis- easecharacterizedbywell-definedneurologicalfeatures:neuronal loss,neurofibrillarytangle,andsenileplaque.However,theclini- calmanifestationsofADasamajorneurocognitivedisorderare mainlypsychiatricwhichincludedementia,paranoia,depression andothercognitivedefects:theDiagnosticand StatisticalMan- ualofMentalDisorders(DSM-5)(AmericanPsychiatricAssociation, 2013).

OscillopathicendophenotypesofADareexploredmainlyphe- nomenologicallyyet,and aresummarizedbelow (Cassanietal., 2018):(1)Slowing.Thepowerspectrumshiftsfromhigh-frequency components (alpha, beta, and gamma) toward low-frequency components (delta and theta) that are commonly seen in the resting-stateEEGmeasurementsofADpatients(Jeong,2004).This shiftisproportional totheprogression ofADand isthoughtto appearduetothedecreaseofcholinergictones.(2)Reducedcom- plexity.Adecreaseinthecomplexityofthebrainelectricalactivity has been observed in AD patients (Jeong, 2004). (3) Decrease in synchronization. Synchronization between brain regions in AD patientsdecreases(Babiloniet al.,2016; Wen et al.,2015).

The synchronization was evaluated using the Pearson correla- tioncoefficient,magnitudecoherence,phasecoherence,Granger causality, phase synchrony, global field synchrony, and cross- frequency coupling. (4) Long-range, effective EEG connectivity (functionalcoupling)decreases(e.g.front-parietal,front-temporal)

(Babiloniet al.,2016).(5) Thedisruptionofdeltawavesduring slowwavesleep(Zott etal.,2018).Theseoscillopathicfeatures were also reported with MEG and fMRI studies (Engels et al., 2017;Greicius,2008).Amyloid-betaandtauproteinpathologies areatleastpartiallycausaltotheseoscillopathicfeaturesofAD becauseamyloid-betapeptidesandtauproteinsaffectexcitatory andinhibitorysynaptictransmissionsandtherebymemoryfunc- tionsinaconcentrationdependentmanner(Gulisanoetal.,2019;

Robersonand Mucke, 2006).Amyloid-beta peptides areknown todisrupt the excitatory/inhibitory balanceby interfering with GABAergicinterneuronsaswell(MablyandColgin,2018).

Furthermore,acuteapplicationofsolubleamyloid-betaalone canacutelyandreversiblydisruptsynchronizingslowwavesacross thecortex,thalamus and HPCduring non-rapideye movement (REM)sleep-likeanaesthetizedmice(Zottetal.,2018).Thereduc- tion in gamma oscillations in AD animal models is commonly observed(MablyandColgin,2018).Inversely,theartificialinduc- tionof gammaoscillationsin thebraindecreasesamyloid-beta depositions,preventsneuronalloss,andimprovescognitivefunc- tionsinADanimalmodels(Adaikkanetal.,2019;Iaccarinoetal., 2016;Martorelletal.,2019).Theintroductionofhigh-frequency oscillatoryactivityintothebrainviafornixDBSdecreasesamyloid- beta deposition in a rat AD model (Leplus et al., 2019) and improves cognitive functions in both AD animal models and patients(Mirzadehetal.,2016).

2.4. Schizophrenia

Schizophreniaisaseverepsychiatricillnesscharacterizedby positive symptomsincluding delusions, hallucinations, orpara- noia,andnegativesymptomsincludingalossofmotivation,apathy, asocialbehavior,lossofaffect,and pooruseandunderstanding ofspeech.Schizophreniapatientsalsohavecognitivesymptoms suchasimpairedworkingmemory,dissociatedthoughtprocesses, andimpairedexecutivefunction(Sontheimer,2015).Becauseof anabsenceofunequivocalbiomarkers,schizophreniaisdiagnosed entirely on the assessment of symptoms by a trained psychi- atric doctor who bases his or her judgment on a number of features described in DSM-5 (AmericanPsychiatric Association, 2013).Therefore,effortshavebeenmadetofindanappropriate biomarkerusingfunctionalbrainimagingtechniques,EEGandMEG recordingsetc.(Meyer-Lindenberg,2010).Forexample,fMRIstud- iesrevealedthatPFCactivitywasreducedinschizophreniapatients (Barchetal.,2001);thePFCgovernsexecutivefunction,taskinitia- tion,motivationaldrive,andworkingmemory.Reducedactivities havebeenreportedontheamygdala(AMY)andtheHPC(Meyer- Lindenberg,2010),whichcouldexplaintheflataffectofindividuals ofschizophrenia.Restingstatenetworkshavealsobeenchangedin schizophreniapatients(Alexander-Blochetal.,2012;Cabraletal., 2012).

Gammaoscillations typically resultfrom thefast, reciprocal interactions of excitatory glutamatergicneurons and inhibitory GABAergicneuronsinthebrain(BuzsákiandWang,2012).These oscillations are thought to support many cognitive functions includingworkingmemoryinthePFC(Benchenaneetal.,2011;

RouxandUhlhaas,2014).Studieshavefoundthatgammaoscilla- tionsweredisruptedinschizophreniapatients(Gonzalez-Burgos etal.,2015;SenkowskiandGallinat,2015)andthatthisgamma disruptioninthePFCpresumablyleadstodisruptedintra-PFCand PFC-HPCcommunications(MoranandHong,2011).Thedecreased gammaoscillations are mediated by hypofunctional GABAergic networks in the PFC (Lewis et al., 2012). This finding is sup- portedbyevidencethatthegeneexpressionof67-kDisoformof glutamicaciddecarboxylase,thekeyenzymeinGABAsynthesis, isreduced inthepost-mortem brainsof schizophreniapatients (Akbarian et al., 1995; Volk et al., 2000).It hasbeen reported

thatrepeatedtranscranialmagneticstimulation(rTMS)ofthedor- solateral prefrontalcortex (DLPFC) restoredgamma oscillations ofschizophreniapatientsand cognitivefunctionsconcomitantly (Farzan etal.,2012).Thisresultsuggestsa possiblecausalrela- tionshipbetweenthereductioninfrontalgammaoscillationand cognitivedeficitinschizophrenia(Pittman-Pollettaetal.,2015).

2.5. Anxietyandtrauma-relateddisorders

Generalizedanxietydisorder(GAD)andpost-traumaticstress disorders (PTSD) are characterizedby chronic and exaggerated anxietyandfear(AmericanPsychiatricAssociation,2013).Concep- tually,thesedisorderscanberelatedto(1)theovergeneralization ofperception,interpretation,andassessmentofinnocuousstimuli and(2)overexpressionofanxietyandfearresponses.Theformeris explainedbythedisruptionofthePFC,patternseparationofthe HPC,andintrinsic sensoryhyperactivityin theprimarysensory cortex.For example,restingEEGrecordingsfromPTSD patients revealedthattherewasdisruptedsensoryprocessingwithintrin- sicsensory hyperactivityinthevisualcortex(suppressed alpha power),decreasedbottom-upalphapower-mediatedinhibitionto thefrontalcortex,andincreasedfrontalgammaband(30–50Hz) poweractivatedbytheintrinsicsensation(Clancyetal.,2017).The lattercanbeexplainedbyenhancedneuralactivityinthenegative emotionnetworks.Forexample,Huangetal.(2014)foundhyper- activitiesintheAMY,theHPC,andtheinsularcortexinresting MEGrecordingsofPTSDpatients,whicharesupposedtopositively correlatewiththeirsymptoms.

Inaddition,Qiaoetal.(2017)foundstrongerfunctionalcon- nectivitywiththeAMY,insularcortex,putamen, thalamus,and posteriorcingulatecortex(whicharenegativeemotioncircuits) inrestingstatefMRIrecordingsofGADpatients.Incontrast,they foundthatweakerconnectionsinthefrontaland temporalcor- tices in GAD patients. Interestingly, they also found decreased effectiveconnectivity(Grangercausality)fromthefrontalcortexes tothe AMY and basal ganglia (Qiao et al., 2017), which is the top-downinhibitoryactivitycontrolofthesubcorticalnetworks.

TheMEGstudyalsoreportedthatthealpha(8–12Hz)activityof PTSDpatientsdecreasedintheDLPFCandventromedialPFC,and italsodecreasedthetop-downalphacausalityfromthesestruc- tures(Huangetal.,2014).OtherrestingstateEEGstudiessupport hypofunctionof thefrontalcortexes in GADand PTSD patients (Crostetal.,2008;Eidelman-Rothmanetal.,2016;Veltmeyeretal., 2006).RodentstudieshaveshowntheroleofthePFCinregulat- ingthelimbicsystemasatop-downcontroloffearexpressionand anxiety,whicharemediatedbythetaoralpharangefunctionalcou- plings(Dejeanetal.,2016;Karalisetal.,2016;Likhtiketal.,2014).

Therefore,on-demandmodulationofthetop-downcontrolmaybe effectiveforsupressingexcessiveanxietyandfearexpression.

2.6. Majordepressivedisorder

Majordepressivedisorder(MDD)isacommonandpersistent psychiatricdisordercharacterizedbyextremefeelingsofsadness andlowmooddisproportionatetoanypossiblecause(American PsychiatricAssociation,2013).MDDresultsin tremendoussoci- etalcosts(Greenbergetal.,2003).Intracranialelectrophysiological recordings from epilepsy patients indicate that mood can be decodedfrommulti-channelLFPrecordingsinthelimbicsystem, includingtheorbitofrontalcortex,thecingulatecortex,theAMY, theHPC,thesuperiorfrontalcortex,andthemiddlefrontalcortex (Reardon,2017;Sanietal.,2018).Vulnerabilitytostressandsus- ceptibilitytodepressionhavebeendecodedfrommulti-channel recordingsin thelimbicsysteminanimalmodelsofdepression (Hultmanetal.,2016,2018).These modelsindicatetheoscillo- pathicnatureofdepression.

TheoscillopathicfeaturesofMDDaresummarizedasfollows (Baskaranetal.,2012;Eidelman-Rothmanetal.,2016;Fitzgerald andWatson,2018):(1)elevatedalphabandactivityinthetem- poroparietalregion;(2)elevatedfrontalthetabandactivity;(3) alphafrontalasymmetry(lefthemispherichypoactivityandright hemispherichyperactivityrepresentedasalpha, theta,andbeta bandactivities);and (4)decreased gammabandactivity.These features relate to MDD symptoms and predict the effective- nessofpharmacologicaltreatmentusingtricyclicantidepressants andselectiveserotoninreuptakeinhibitorsandelectroconvulsive therapy (ECT).Thissuggests theirusefulnessas a biomarkerof depression disorder. In addition, fMRI studies suggest that the DMN,thecognitivecontrol network,and theaffective network werefunctionallyhyperconnectedindepressionpatients(Sheline et al., 2010).Functional decoupling of these networks by neu- romodulationtechniquesmayrelievedepressionsymptoms(Fox etal.,2012;Listonetal.,2014).

Furthermore,theremaybecausalrelationshipsbetweenoscil- lationdisturbancesanddepressionsymptoms.First,restorationof thefrontalalphasymmetryusinganodaltranscranialdirectcurrent stimulation(tDCS)ontheDLPFC(Looetal.,2012)andspecifically neurofeedback(Mennellaetal.,2017)improveddepressionsymp- toms.In addition,subanaestheticdoseof ketamine(0.5mg/kg) reduceddeltaoscillations(1–5Hz)andincreasedgammaoscilla- tions(45–85Hz)inthehumancortexand improveddepressive modeofpatients(Bermanetal.,2000;Hongetal.,2010).Further- more,highfrequency rTMSonthe leftDLPFCincreasedresting stategammaoscillationsinthefrontalcortexandimprovedthe depressedmoodinpatients(Nodaetal.,2017).Thesepathologi- caloscillationscanbetargetedusingmolecular(pharmacological), network(neuromodulation),andcognitive(behavioural)methods tointerrogatedepressionsymptoms(Leuchteretal.,2015).

2.7. Drugaddiction

Drug addiction (also known as substance usedisorder) is a chronically relapsing disorder characterized by persistent drug seeking and drug-taking behaviors despite significant negative physical,emotional,socialandoccupationalconsequences(Volkow andMorales,2015).Drugaddictionprogressesfromanimpulsive toacompulsiveintakeinacollapsedcyclethatconsistsofthree stages:(1)preoccupation/anticipation,(2)binge/intoxication,and (3)withdrawal/negativeaffect(Koob andVolkow,2010).Atthe beginning, the voluntary or impulsive intake induces euphoria during the binge/intoxication stage and positive reinforcement willdrivethenextintake.Afterestablishmentofmaladaptation (addictedstate),negativereinforcementcausedbyreliefofanxiety, stress,and/orrestlessnessduringabstinencewillbeadriveforfur- therintake(Volkowetal.,2016).Inthepreoccupation/anticipation stage,patientshaveacraving,andobsessiontogetdrugs.

Inaddictedbrains,manyneuroadaptationshappenfromepige- netictoneurocircuitlevels.Theseneuroadaptationscontributeto chronic,obsessivedrugintakebehaviorsandimpulsivedecision- makinginthepreoccupation/anticipationstage.Forexample,the neuralactivityofthePFCisreduced(hypofrontality)inaddicted patients(e.g.smokers)(GoldsteinandVolkow,2011;Zilverstand etal.,2018).Thisreducedactivitywouldpresumablybeacause ofimpulsivedecision-makingofaddictedpatients(Bechara,2005) becausethePFCgoverns analysis,prediction,andtheexecutive controlofrewardseekingbehaviors(KennerleyandWalton,2011).

AbnormalfrontalEEGmeasurementsduringtherestingstate arealsoobservedinopioidusers(Motlaghet al.,2017), alcohol abusers(Huang et al., 2018), tobacco smokers (Liet al., 2017), cannabisusers(Prashadetal.,2018),andpsychostimulantusers (Newtonetal.,2003),althoughtheirabnormalitiesaredependent ondrugmodalities(NewsonandThiagarajan,2019).Theoscillation

abnormalityinthefrontalcortexiscontextdependentaswell.For example,frontalasymmetry(leftlateralizationeffects,lessalpha oscillationinthelefthemisphere)occurredincocaineabusersin responsetolosingontheirchoiceofimmediatelargerewardsdur- ingtheIowagamblingtask(Balconietal.,2014).Thesedisrupted frontaloscillatoryactivitiesarealsorepresentedbythereduction ofthetop-downinhibitorycontrolcalledtheexecutivecontrolnet- work(ECN),which for examplecontrolsthedesire saliencefor drugs(Bechara,2005).TogetherwiththeDMNandthesaliencenet- work,thedecreasedECNactivityisagoodpredictorofthecravings ofchronictobaccosmokers(Lermanetal.,2014;Sutherlandetal., 2012).TherestorationoftheECNbyrTMSoftheleftDLPFCalle- viatednicotinecravingwithsignificantEEGpowerchanges(Pripfl etal.,2014).

Therefore, an obsessive drug taking habit driven by drug craving and impulsive decision-making during the preoccupa- tion/anticipation stage may be treated with non-invasive or invasivestimulation(Dandekaretal.,2018;Dianaetal.,2017),or cognitiveinterventions(Zilverstandetal.,2016)bymodulatingthe oscillatingnetworkswherethePFCiscentral.Negativereinforce- mentduringthewithdrawal/negativeaffectstage(whichcanbe mediatedbydeltaandgammabandactivitiesinthelimbicsys- temincludingthePFCandthenucleusaccumbens(NAc)(Dejean etal.,2013,2017))maybeintervenedbyDBSornon-invasivestim- ulation(Dandekaretal.,2018;Dianaetal.,2017).Positivevalence duringthebinge/intoxicationstage(whichispresumablymediated bydelta-bandactivityintheNAc(Wuetal.,2018))maybereplaced byDBSoftheNAcorthemedialforebrainbundle(Dandekaretal., 2018).Thesefactsindicatetheoscillopathicfeaturesofdrugaddic- tionandthepossibleapplicationsofoscillotherapeutics.

3. Mappingofoscillopathies

Appropriate animal models for each disease or disorderare requiredtofacilitatedevelopmentofoscillotherapeutics.Appro- priaterecordingtechniquesfortheoscillatingneuronalactivities ofanimalmodelsandhumansareindispensable,asareefficient analyticalmethods.Thus,hereweprovideanoverviewofhowthe pathologicaloscillationsofneurologicalandpsychiatricdisorders arerecordedanddetected(the‘diagnostic’inresearchandclinics).

3.1. Animalmodels

3.1.1. Animalmodelsforepilepsy

Animalmodelsforepilepsyresearcharethoroughlysumma- rizedin thebook ofPitk ¨anen etal.(2017).Briefly, theepilepsy modelsareclassifiedbyseizuretypes(generalizedorfocal,petit malorgrandmal),animalspecies(mice,rats,catsetc.),whether invitroorinvivo,whethergeneticoracquired,whetheracuteor chronic,andhoweachseizureisevoked(electrical,chemical,sen- soryinputs,spontaneousetc.).

Chronic spontaneous seizure modelsare typically employed forthedevelopmentoftime-targetedclosed-loopinterventions.

Tottering(tg)andStargazer(stg)mousestrainsareavailableto studyabsence(petitmal)seizureswithspike-and-wavedischarges.

These strainshave knownmutation onalphaand gammasub- unitsofvoltage-dependentcalciumchannels,respectively(Upton and Stratton, 2003).Two inbred strains are for example avail- ableforratexperiments:thegeneticabsenceepilepsyratsfrom Strasbourg(GAERS)andtheWistarAlbinoGlaxostrain(WAG/Rij) (CoenenandvanLuijtelaar,2003;Danoberetal.,1998).Thespike- and-wavedischargesareseeninordinaloutbredlaboratoryrats andeveninwild-caughtratsaswell(Tayloretal.,2019).Absence seizurescaninducedacutelybysystemicadministrationofasingle pharmacologicalcompound[4,5,6,7tetrahydroxyisoxazolo(4,5,c)

pyridine3-ol(THIP),lowdosepentylenetetrazole(PTZ),orgamma- hydroxybutyrate]inrats(Farielloand Golden,1987; Marescaux et al., 1984; Snead, 1988) and chronically by prepuberty sys- temicadministrationofAY-9944ormethylazoxymethanolacetate (MAM)-AYinrats(Cortezetal.,2002;Serbanescuetal.,2004).

ThesystemicinjectionofGABAAreceptorantagonists(e.g.PTZ, bicuculline,picrotoxin)caninduceacutegeneralized convulsion seizuresinrodents(Mackenzieetal.,2002;Veliseketal.,1992;

Velíˇskováetal.,1991).Thesystemicinjectionofglutamaterecep- toragonists (e.g.kainicacidandNMDA) ormuscarinicreceptor agonists(e.g.pilocarpine)canalsoinduceacute,generalized,con- vulsiveseizuresinrodents(Ben-Arietal.,1981;MareˇsandVeliˇsek, 1992;Turskietal.,1983).Inaddition,theinhalationofflurothylcan beused(Prichardetal.,1969),alongwithintracranialinjectionsof bicuculline,picrotoxin,kainicacidandotherdrugstoinduceacute convulsiveseizuresinrodents(Ben-Arietal.,1980;Sierra-Paredes andSierra-Marcu ˜no,1996;Velíˇskováetal.,1991).Achronicsponta- neous,limbicseizurerodentmodelcanbepreparedbytherepeated systemicinjectionofPTZ,kainicacid,orpilocarpine(Cain,1981;

Cavalheiroetal.,1991;Hellieretal.,1998),asingleintrahippocam- palinjectionofkainicacid(Braginetal.,1999),orrepeateddaily electricalstimulationofthelimbicstructure(e.g.theAMY,HPC) (Goddardetal.,1969;McIntyreandGilby,2009).Geneticmodels forspontaneousconvulsiveseizuresareavailablebothinmouse andratstrains(e.g.weavermice,NER/Kyorats)(Serikawaetal., 2015;UptonandStratton,2003).Auditorystimulationcaninduce- convulsiveseizuresinthegenericallyepilepsy-pronerats(GEPRs) andDBA/2mice(DeSarroetal.,2017).

3.1.2. AnimalmodelsforParkinson’sdisease

Animal models of PD are classified into neurotoxin models and genetic models (Gubellini and Kachidian, 2015). 6-OHDA (6-hydroxydopamine) and MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine)aretypicallyusedtomimic selectivelossof nigrostriataldopaminergicneuronsviamechanismbywhichmito- chondrialcomplexIisblocked(Tieu,2011).Bothneurotoxinsare usedinrodentandnon-humanprimateexperiments.

SystemicallyadministeredMPTPcaneasilycrossthebloodbrain barrierwhereas 6-OHDAshouldbestereotaxicallyinjectedinto thetargetbrainstructure(usuallythesubstantianigraparscom- pacta(SNc),themedialforebrainbundle,orthestriatum).6-OHDA andMPTPadministrationsleadtosignificantPD-likemotorsymp- tomsincludingakinesia, freezing, bradykinesia, musclerigidity, abnormalposture,stereotypyandtremorassociatedwithsignif- icantdegenerativelossofSNcdopaminergicneurons(Smeyneand Jackson-Lewis,2005).Neither6-OHDAnorMPTPadministration induces Lewy body-like inclusions withalpha-synuclein (Cenci etal.,2002).Importantly,boththe6-OHDArodentmodelandthe MPTP-treatedmonkeysexhibit pathological oscillationsintheir basalgangliaasfrequentlyobservedin humanpatients:tremor (4–7Hz),doubletremor(10Hz),andbeta(15–30Hz)(Deffainsand Bergman,2019;Heimeretal.,2006).Mutationsofcausalgenesor geneticriskfactorsofParkinson’sdiseasearemodelledinmiceand ratsincludingSNCA(alpha-synuclein),PRKN(parkin),PINK1(PTEN- inducedputativekinase1),DJ-1(PARK7)andLRRK2(leucine-rich repeatkinase2).Thesemodelsofferwaystostudypathologyas Lewy-bodylikeinclusions,buttheyexhibitonlymildmotorsymp- toms.Pathologicaloscillationsinthebasalgangliainthesegenetic modelshavenotbeenstudiedwellyet.

3.1.3. AnimalmodelsforAlzheimer’sdisease

MostADpatientsaresporadicandtherearesomeanimalmodels forsporadicADusingmetabolicandtraumaticbraininjury-induce damageetc.(Zhanget al.,2019).However,thevastmajority of currentADanimalmodelsaretransgenicrodents(mainly mice) andarebasedontheamyloidandtauhypotheses,andthegenet-

icsofthefamilialformofthedisease(MullaneandWilliams,2019).

Nearly170transgenic/knock-in/knock-outmodelsofADhavebeen developedtodate(ALZFORUMResearchModelsDatabase;https://

www.alzforum.org/research-models).Theyareprincipallyfocused onmutationsinAPP(Amyloidprecursorprotein),PSEN1(prese- nilin 1),MAPT (microtubule-associated protein tau), and Trem2 (Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2), and APOE (apolipoprotein E), as well as the transfection of the amyloid processingenzyme,BACE1 (Beta-Secretase1)(Götzetal.,2018;

MullaneandWilliams,2019).Themodelanimalshavesingleor multiplemutationsofthesegenes.Forexample,3×Tgmice,which haveAPPKM670671NL(Swedish),MARPTP301L,andPSEN1M146 Vtriplemutations,showamyloidbetaplaque,hyperphosphory- latedtau,andneurofibrillarytangleaspathologicalphenotypesand deficitsinworking,spatial,andfearconditioningmemory(Oddo etal.,2003).5×FADmicehavethreemutationsonAPP(Swedish, Florida, London) and two mutations onPSEN1, and theyshow amyloid-betaplaqueandmemorydeficitsassoonastwomonths old(Oakleyetal.,2006).Inthetaupathologymodel,rTg4510mice withMAPTP301Lmutationhaveneurofibrillarytangle,neuronal lossandmemorydeficitsasphenotypes(Santacruzetal.,2005).

TheoverexpressionofmutanthumanAPOE4protein(ariskfactor ofAD)inAPOE4-KImiceresultsinsignificantmemoryimpairment aswell(Sullivanetal.,2004).

Importantly,all these AD models(3×Tg,5 × FAD, rTg4510, APOE4-KI)consistentlyshowareductionofslowgammaoscillation intheCA1ofHPC(Boothetal.,2016;Gillespieetal.,2016;Iaccarino etal.,2016;Mablyetal.,2017),whichcontributestotheencoding andretrievalofmemory.CA1placecellrepresentationsofspace wereunstableinthesemiceandthedeficitsinslowoscillations intheHPCwereconcomitantwithspatialmemory.Surprisingly, theoptogeneticactivationofparvalbumine(PV)-interneuronsat slowgammafrequencies(or40Hzlightflickersensorystimula- tion)reducedamyloid-betadepositionsinthebrainandrestored cognitiveimpairmentoftheADmicemodel(Iaccarinoetal.,2016;

Martorelletal.,2019).

In the APP23 × PS45 mouse model (Busche et al., 2008), thecoherenceofslowwavesbetweendifferentcorticalregions, thethalamus, andtheHPC iscompletelydisrupted in thelight anesthesia condition (Zott et al., 2018). This resembles dis- rupted,slow-waveoscillationsduringnaturalnon-REMsleepinAD patients(Wineretal.,2019).Thecoherentslowwaveoscillations were transiently disrupted in wild-type mice by the applica- tionofsolubleamyloid-beta,whichsuggestsacausalrelationship betweenamyloid-betaandthepathologicaloscillationpatternin AD(Buscheetal.,2015).

3.1.4. Animalmodelsforschizophrenia

Animalmodelsofschizophreniamostlyfitintooneoffourdif- ferentinductioncategories:developmental,drug-induced,lesion orgeneticmanipulationmodels(Jonesetal.,2011).Examplesof neurodevelopmentalmodelsincludegestationalMAMinjections, bacterial or viral infections, and post-weaning social isolation;

pharmacologicalmodelsincludeamphetamine-inducedpsychosis, NMDA antagonist [phencyclidine (PCP), MK-801, ketamine)]- inducedpsychosis; lesionmodels include neonatalventralHPC lesion;geneticmodelsincludevariousknock-outormutantmodels ofschizophrenia susceptibilitygenes,someof whichwerevali- datedbygenome-wideassociationstudies(SchizophreniaWorking GroupofthePsychiatricGenomicsConsortium,2014).

Thesemodelsresemblevariouscognitivesymptomsfoundin schizophreniapatientsincludingdeficitsofsensorimotorgating, workingmemory, visio-spatialmemory, andobject recognition, aswellasdecreasedsocialinteraction,increasedlocomotion,and exaggeratedsensationetc.Themodelsalsoshowcellularorcir- cuit level alterations including decreased synaptic connections,

andspinedensities, thelossofprefrontalPV-positiveinterneu- rons, the loss of dendrites in cortical pyramidal neurons, and pathological oscillations (e.g. dysfunctional prefrontal gamma oscillations).Thepathological oscillationstiethecellularorcir- cuitlevelpathophysiologytoalterationsinlocalprocessingand large-scalecoordination,andinturnmayleadtocognitiveandper- ceptualdisturbancesobservedinschizophrenia(Pittman-Polletta etal.,2015;SenkowskiandGallinat,2015).

A number of schizophrenia-susceptibility genes have been identified on chromosome 22. These include DISC1(disrupted- in-schizophrenia1),NRG1(neuregulin1)anditsreceptorERBB4 (erb-b2receptortyrosinekinase4,erbB-4),andCOMT(catechol- O-methyltransferase). DISC1 is a synaptic protein that plays a crucialrole insynaptogenesis(BennettAO,2008).Mutationsor thefunctionaldisturbanceofDISC1leadtothedisruptionofPV- positive interneuron cytoarchitecture and hypofunction in the cortexandHPC,whichiscriticalfornormaloscillatoryactivityin thebrain(Koyamaetal.,2013;Nakaietal.,2014).NRG1andERBB4 arealsosynaptogenicschizophreniasusceptiblegenes(Meiand Xiong,2008).Theirdisruptionresultedinabnormalgammaoscil- lationsintheHPCanddisruptedfunctionalcouplingbetweenthe ventralHPCandNAc (Koyamaet al.,2013;Nasonet al.,2011).

Reduced dysbindin-1 (another synaptic protein from suscepti- blegeneDTNBP1(DickmanandDavis, 2009))isassociated with reducedphasicactivationofPV-positiveinterneuronsandreduced gammaoscillations(Carlsonetal.,2011).

Oneofthelargestriskfactorsforschizophreniaisthemicrodele- tion of chromosome 22q11.2 that wipes out up to 60 genes;

the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome results in facial abnormalities, heartdefects,andanumberofneuropsychiatricconditions(Jonas etal.,2014).Aquarterofthepatientsthat havethemicrodele- tion of this chromosome develop schizophrenia. Importantly, in the Df(16)A+/− mouse model of this micro delision, mice exhibited reduced PFC-HPC synchrony,represented by reduced phase-lockingofPFCneuronstoHPCthetaoscillationanddisrupted coherence across multiple frequency ranges (delta to gamma ranges)(Sigurdssonetal.,2010).

Aspharmacologicalmodels,NMDAreceptorblockerssuchas ketamineandPCPareknowntoinducedelusionsandhallucina- tionsinotherwisehealthysubjects(Krystaletal.,1994).Ketamine isknowntoattenuatebothbackgroundandsensoryevokedtheta powerintheCA3inmice.Itenhancesbothbackgroundandevoked gammapower,but itdecreasesrelative-inducedgammapower (Lazarewicz etal.,2010).Thissuggeststhat ketaminedecreases thesignal-to-noiseratioofgamma-bandactivityandpossiblyleads todisruptedpatternseparationfunctionintheCA3region,con- tributingitsdissociativefeeling.KetaminereducesNMDAreceptor functionpreferentiallyonPV-positiveinterneurons,whichimpairs HPCsynchrony,spatialrepresentations,andworkingmemoryin mice(Korotkovaetal.,2010).TheNMDAhypofunctionalsoreduces deltaandthetaactivityinthecortexandHPC(Kissetal.,2013).

Ketaminealsodisruptsthethetamodulationofgamma-bandactiv- ityand reducesnetworkresponsibility totheenvironmentin a computermodelofHPC(Neymotinetal.,2011).

Asa gene-environmentinteractionmodel,WISKET ratswere reportedasa selectivelybred linewithschizophrenia-like phe- notypes(reducedsensorimotorgating,hyperalgesia,andmemory deficit)afterpost-weaningsocialisolationandchronicketamine treatmentover 15 generations (Bükiet al., 2018).The WISKET ratsshowedincreasedtheta,alpha,andbeta-bandactivitiesand reducedgamma-bandactivitiesinECoGrecordings(Horvathetal., 2016).

3.1.5. Animalmodelsforanxietyandtrauma-relateddisorders Animalmodelsfor anxietyand trauma-relateddisorders are classifiedintofivemodels:experience-based,pharmacologic,phar-

macologicallesion,selectivelybredgenetic,andspecifictransgenic (Hoffman,2016).Examplesof experience-basedmodelsinclude fearconditioningandextinction,pre-weaningstress,andmater- naldeprivation.Pharmacologicmodelsincludeyohimbine(alpha-2 adrenergicreceptorantagonist),CCKtetrapeptide(CCK-4,ananx- iogenic neuropeptide),caffeine (adenosinereceptor antagonist), m-chlorophenylpiperazine (serotonin 5-HT2C receptor antago- nist), and FG7142 (benzodiazepine partial inverse antagonist).

Pharmacologicallesionmodelsincludethechronicinfusionofl- allylglycine(aninhibitorofglutamicaciddecarboxylase)intothe dorsomedial/perifornicalregionofthehypothalamus(DMH/PeF)in rats(JohnsonandShekhar,2012).Selectivelybredgeneticmodels includeRomanHighandLowAvoidancerats(Escorihuelaetal., 1999), Sardinian alcohol-preferringrats (Colombo et al., 1995), HighanxietybehaviorandLowanxietybehaviorrats(Yilmazer- Hanke et al., 2004), Floripa H and L rats (Ramos et al., 2003), Ultrasonicrats(BrunelliandHofer,2007),andHighanxietybehav- iormice(Erhardtetal.,2011).Specifictransgenicmodelsinclude 5-HTtransporterknockoutmice,brain-derivedneurotrophicfac- tor (BDNF) Val66Met mice, COMT and monoamine oxidase A deficient mice, 5-HT1A knockout mice, corticotropin-releasing hormone overexpression mice, and neuropeptide Y-knockout mice.

Theirendophenotypescan bemeasuredasstartlereactivity, behavioralinhibition(viatheopenfieldandelevatedplusmazes, as wellas the light/dark, social interaction, and punished con- flicttests),carbondioxidesensitivity(avoidanceofaCO2-enriched environment,exploratorybehaviorafterexposuretoCO2-enriched air,tidalrespiratoryvolumeduringexposuretoCO2-enrichedair), andfearover-generalization(discriminationofCS+andCS−stimuli afterfearconditioning).Recentstudieshaverevealedthatdistinct oscillatoryactivitiesinspecificPFC-AMY-HPCnetworksarerelated tobothfear/anxietyexpressionanditsregulations(C¸alıs¸kanand Stork,2019;Dejeanetal.,2016;Karalisetal.,2016;Likhtiketal., 2014).

3.1.6. Animalmodelsfordepressivedisorders

Animalmodelsfordepressivedisordersareclassifiedintofive models: experience-based, pharmacologic, lesion, genetic, and gene-environmentinteraction(Hoffman,2016).Experience-based models include learned helplessness, chronic adult stress (e.g.

overnight illumination, water or food restriction, tilting cages, social isolation or crowding etc.), early life stress (e.g. mater- nal separation), and social stress (e.g. chronic social defeat).

Pharmacological modelsincludewithdrawal frompsychostimu- lant use. Lesion modelsinclude bilateralolfactory bulbectomy.

Genetic models include selectively bred lines (e.g. the Rousen depressedmouseline,FlindersSensitiveLinerats,WisterKyoto rats, Fawn Hooded rats, SwLo/SwHi rats, cLH rat lines) (El Yacoubiet al.,2003; Hennand Vollmayr,2005; Overstreet and Wegener,2013;Rezvanietal.,2007;Willetal.,2003),andspe- cific transgenic lines (e.g. 5-HT transporter knock-outrats and mice, BDNF promoter IV-mutant mice, BDNF Met mice) (Chen etal.,2006;Sakataetal.,2010;Wisor etal.,2003).Theircogni- tive/behavioralphenotypessuchasanhedoniacanbemeasured using thesucrose preference test, conditionalplace preference, intracranialself-stimulation,variableprogressiveratioreinforce- ment, andresponse biasprobabilistic rewordtask; theycan be measuresasnegativeprocessingbiasusingincreasedreactivityto aversivestimuli,probabilisticreversallearning,andreactivityto emotionallyambiguouscues.Somephysiologicalendophenotypes (e.g.sleeppatternchanges)arerecapitulatedaswellintheserodent models.

Recently,stressvulnerabilityanddepressionsusceptibilitywere successfullydecodedfromlarge-scaleelectrophysiologicalrecord- ingsasdistinctoscillationpatternsinfreelymovingmice(Hultman

etal.,2018).Thespecificoscillationpatternsforthevulnerability and susceptibilityare consistentwiththeresults ofpharmaco- logical(interferonadministration)andearlylifestress(maternal separation).

3.1.7. Animalmodelsfordrugaddiction

Animal models for drug addiction can be classified into models for the three stages: preoccupation/anticipation, binge/intoxication,and withdrawal/negativeaffectstages (Koob andVolkow,2010).

Animalmodelsforthepreoccupation/anticipationstagefitinto two categories: extinction-based and abstinence-based relapse models(Venniro et al., 2016).Extinction-based relapse models includedrug-,cue-,context-,stress-,andwithdrawalstate-induced relapses (Alleweireldt et al., 2001; Shaham et al., 2003), reac- quisition(Boutonetal.,2012),andresurgence(Winterbauerand Bouton,2011).Abstinence-based relapsemodels include forced abstinenceanddrugcravingincubation(Fuchsetal.,2006),adverse consequences-imposedabstinence(Cooperetal.,2007),andvolun- taryabstinenceinducedbyintroducingnon-drugrewards(Caprioli etal.,2015).Inaddition,riskyandgamblingchoicetasksandthose withreward/aversionconflictscanbeusedtostudythepathologi- caloscillationsunderlyinginappropriate,impulsiveandexecutive decisionmakinginaddictedstates(Passeckeretal.,2019;Verharen etal.,2018).

Animalmodelsofthebinge/intoxicationstageconsistofintra- venousandoraldrugself-administration(AhmedandKoob,1998), intracranialself-stimulation(MarkouandKoob,1992),conditional placepreference(Sanchis-Seguraand Spanagel,2006), drugdis- crimination(Stolermanetal.,2011),andgeneticmodelsofhigh addictionsusceptibility(Quintanillaetal.,2006).Inaddition,the drugtakinginthepresenceofaversiveconsequencesmodelcanbe usedtofindpathologicaloscillationsgoverningcompulsivedrug takingbehavior(Vendruscoloetal.,2012).

Animalmodelsofthewithdrawal/negativeaffectstageinclude intracranialself-stimulation(rewarddecreases),conditionalplace aversion(Handetal.,1988),measuresofanxiety-likeresponses (e.g. the open field and elevated plus mazes), and drug self- administration with extended access or in dependent animals (Ahmedetal.,2000).

3.2. Neuralactivityrecordings 3.2.1. Foranimalresearch

Large-scalebraindynamicsrecordingsasLFPsareverypow- erfulfor investigatingoscillatoryactivitiesacrossmultiplebrain regions(HongandLieber,2019;Pesaranetal.,2018).Beyondsin- glesiterecordings,multi-siterecordingswithsiliconprobeshave allowedthegeometryofoscillatoryactivitiesinthebraintobe studied(WiseandNajafi,1991).Linear16–32chrecordingprobes havebeenusedtomaplayerspecificoscillationsforexamplein thecortex(Minlebaev etal., 2011).Recent CMOS-basedprobes (Neuropixel)enableupto960chhigh-densityrecordingsonasin- gleshank(Junetal.,2017).Multi-shanklinearsiliconprobes(e.g.

buz256)cancapturetwo-dimensionalspatiotemporalstructureof oscillationsinabrainregion(Agarwaletal.,2014;Berényietal., 2014).Forexample,Olivaetal.foundthatsharp-waverippleinthe CA2subregionprecedesthoseintheCA1andCA3subregionsinthe ratHPC(Olivaetal.,2016).

Theinsertionofmultiplesiliconprobesand/orwireelectrodes intodistinctbrainregionsallowedoscillatoryinteractionsbetween brainregionstobeexploredduringspatialnavigation(Fernández- Ruizetal.,2017),goal-directedbehaviors(FujisawaandBuzsáki, 2011),epilepticseizures(Berényietal.,2012),anxiogeniccondi- tions(Girardeauetal.,2017),depression(Hultmanetal.,2018), anddrugaddiction(Sjulsonetal.,2018).Matrixsiliconprobescan

beusedtoobtainhigh-densitythree-dimensionaloscillationactiv- itiesinthebrain(Riosetal.,2016),andflexiblemeshelectronics usedinsteadof rigidelectrodesenableyear-long stablerecord- ings(Hongetal.,2018).Two-dimensionalelectrodesonflexible polymersheetsenablepotentialrecordingsfromthecorticalsur- face(Khodagholy etal., 2015).Simultaneous recording ofbrain andotherphysiologicaloscillations(e.g.electrocardiogram,elec- tromyogram, and breathing) from freely-moving animals is an importanttechniquetostudypathophysiologicalrepresentations ofneuropsychiatricdisorders(Sasakietal.,2017).

3.2.2. Forclinicalpractice

Theinternational10–20or10–10EEGrecordingsystemsare widelyusedforstandarddiagnosisorstudyofavarietyofneu- ropsychiatricdisorders, includingepilepsy(Nuweret al.,1998).

OneoftheadvantagesofEEGrecordingsisitstimeresolution.This enablesfastoscillatoryactivitiestobeanalyzed(typically0.3–300 Hz).MEGrecordingshaveanevenhighertimeresolution(inmil- liseconds).Thefrequencyspectrumdensityineachrecordingsite andtherelationshipsbetweentherecordingsites(coherency,con- nectivity,causalityetc.)aretypicallyanalyzed.High-densityEEG recordings(64–256ch)increasespatialresolutionandallowsource imagingwithevensub-lobarprecision(Seeck etal.,2017).This enablesbetterspatialresolutionforseizurefocuspredictionwith tomography.fMRIrecordingsgivehigherspatialresolution(inmil- limeters)butlowertimeresolution(inseconds)comparedtoEEG recordings;theyprimarilyutilizetheblood-oxygen-leveldepen- dentcontrast,whichis complementarytoEEGrecordings.fMRI recordingscanbeusedtoinvestigateveryslowoscillatoryactivities withinandbetweenbrain regions.Invasiveelectrophysiological recordingsonorinthebrainarerequiredtofindtheseizurefocus muchmorepreciselyortheoptimallocationofDBSelectrodesin thebasalgangliaofPDpatients.

3.3. Machinelearning-mediatedapproachesforanalysis

Itischallengingtofinddiseaseordisorder-specificoscillation patternsinlarge-scaleneuronalactivitydata.Forexample,unsu- pervisedlearning techniqueshavebeenused tofindsignificant coherentresting-statefluctuationsandfunctionalconnectivityof resting-statefMRIdata(Khoslaetal.,2019).Unsupervisedmethods likeindependentcomponentanalysis(ICA)andprincipalcompo- nent analysis (PCA)decomposition are also used tofind latent variable models in fMRI data. Deep learning methods such as convolutionalneuralnetworksandfeedforwardneuralnetworks wereusedtosuccessfullydiscriminatethefMRIdataofADand schizophreniapatientsfromthoseofhealthycontrolpatientswith 96.85%and85.8%accuracy,respectively(Wenetal.,2018).These machinelearningmethodscanalsobeappliedforelectrophysi- ological datatofinddisease-specificoscillation patternsinEEG orintracranialLFPdatafromhumansandexperimentalanimals (Reardon,2017).However,ifthedisease-specificoscillationmodel is extractedby PCA,the modelis soabstract that it cannotbe interpretedwellenoughtodevelopaninterventionbasedonthe analysis.

Recently,Gallagherand otherssuccessfully developedanew modelingalgorithmformulti-regionLFPrecordings(cross-spectral factoranalysis,CSFA).Thisalgorithmbreakstheobservedsignal intofactorsdefinedbyuniquespatiotemporalspectralproperties (apowerorcross-spectraldensities)(Gallagheretal.,2017).The criticalthingisthatthefactorsareinterpretable.Combinedwith asupervised-learningalgorithm,CSFAhasrevealedsymptomspe- cificoscillationpatternsindepression(Hultmanetal.,2018).

4. Oscillopathy–therealisticviewofpathological oscillatorystatesandastrategyforoscillotherapeutics

Herewedescribethepathophysiologyofoscillopathieswithan emphasisonepilepsyasa systemof multistabledynamicoscil- latorystates.We alsoprovideaconceptualoverviewonhowto intervenewithpathological oscillationsfocusing onthecontrol ofepilepsyandepilepticseizuresinatime-targetedclosed-loop manner.

4.1. Bistableormultistablecircuitstates

4.1.1. Modellingconceptandexampleofseizuremodel

Epilepsyisanetworkdisorderwhichcanbecharacterizedby bistableormultistableoscillatorystates(e.g.interictaland ictal states)andthetransitions betweenthem (Kalitzin etal.,2019).

Circuit-state dynamics are determined by the stability of each stateandprobabilityoftransitionbetweenstableoscillatorystates, whicharesupposedtobeaffectedbythefollowingfactors:(1)net- workresonance,(2)resilience,(3)perturbation,sensoryinputs(e.g.

awell-timedpulseinput),(4)neuromodulatoryinputs,and(5)time spentinthestate(Changetal.,2018).

Stableoscillatorystatesincludeatleastnormal(interictal)and hypersynchronousictalstates.Thisconcepthasbeenvalidatedin invivoanimalandhumanrecordingsandinsilicomodellingstudies.

Forexample,thetafrequencyMSstimulationstabilizedoscillatory activityinthesepto-hippocampalaxisanddecreasedseizuresus- ceptibilitywhereasover20HzMSstimulationinducedtransition fromnormaltoictaloscillatorystateinrats(Fisher,2015;Miller etal.,1994).Modellingstudieshavesuccessfullyestablishedrealis- ticbehaviorsofepilepticnetworks,whichresemblenetworkstates including,normalstates,pre-ictalrecruitment,epilepticseizures, andpost-ictalsuppression(Baueretal.,2017;Jirsaetal.,2014).The seizuremodelscanrecapitulateoscillatorystatetransitionsinclud- ingtheonset,evolution,andterminationofepilepticseizures.They helptoexplainmechanismsunderlyingthestatetransitionsand theymayenableupcomingseizurestobepredicted.Theymayalso enablesecondarygeneralizationandpossiblysuddenunexpected deathinepilepsytobeexplained(Kuhlmannetal.,2018).Model- ingstudieshavealsoexplainedthepathologicaloscillationsofPD (Pavlidesetal.,2015;Shounoetal.,2017).

4.1.2. Generationofhypothesisandquantificationofcircuitstates Modellingstudiesarenotmerelyexplanatorytoolsbutalsoan instrumenttogenerateahypothesis.Theycanalsoprovideread- outsofotherwisecomplexstateindicators(Kalitzinetal.,2019).For example,CSFA(Gallagheretal.,2017),machinelearning-assisted modellingofmulti-siteoscillatorynetworks,hasrevealedprevi- ouslyunknownpathologicaloscillationsfordepression(Hultman etal.,2018).Inamultistatemodelstudy,theseizuresusceptibility ofaninstantaneousnetworkstatecanbereadoutasa’separatrix proximity’fortheclosenesstoictaltransition(Petkovetal.,2018).

Thisismeasureofinstantaneousdistancebetweenthecurrentnet- workstateandthethresholdfortheictal(hypersynchronousstate).

Usingthispossiblebiomarkerofseizuresusceptibility,epilepsyis consideredasastatewheretheaveragenetworkoscillatorystate isclosetotheictalthreshold.Physiciansorresearcherscanesti- matetheeffectivenessoftreatmentsornewinterventiontechnique withthisbiomarker.Thisstrategyisquiteeffectiveforpredicting upcomingseizures,andfordevelopinganewtherapeutictechnol- ogyinaverytime-efficientmanner.Seizuresusceptibilityisnot currentlytitrateddirectlybutestimatedbyseizureoccurrencefre- quency,whichistimeconsumingandhashighuncertaintydueto sparseness.CSFAcanbeusedinsteadtoinstantlyquantifyitonce thepathologicalpatternhasbeenmodelled;instantaneousamount

ofadisease-specificoscillationpatternisquantifiedasaspectral factorscore(Gallagheretal.,2017;Hultmanetal.,2018).

Giventhehypothesisandthequantitativemeasureofpatho- logicaloscillatorynetworkstates,thefollowingoscillotherapeutic strategieswouldbeeffectivetocontrolepilepticseizures:(1)intro- ducing oscillatory activity which resonates with and stabilizes non-seizurestates(e.g.thetaoscillationintheHPC),(2)reducing thenormaltoictaltransitionratebyreducingseizuresuscepti- bility,especiallyduringaseizurepredictionperiod,(3)inducing immediatetransitionfromictaltonormalstates byintroducing ahugeoscillatorydisturbanceonictalhypersynchronousoscilla- tions,(4)interveningtopreventoranyintermittentpathological oscillationswhichwouldinducemaladaptationinneuralnetworks.

Thesestrategiescouldbeeffectiveforinterveninginotheroscil- lopathieswithfastoscillatorystatetransitions,includingPDand possiblyforthepsychoticattackofschizophrenia,forimpulsive andaddicteddrugintake,andforanattackofPTSD.

For other oscillopathies withmuch slower underlying state transitions(e.g.GAD,depression,addictioncraving,andAD),long- lastingplasticchangesinoscillatingnetworkdynamicswouldbe requiredtobeinducedbyexternaloscillatoryinterventions.For example, on-demand deletion and the continuous introduction of oscillationsfornegativeand positive feelings mightimprove depressionsymptoms.

4.2. Stimulationstrategies

Pathologicaloscillationsareintervenedinanopen-orclosed- loop manner in terms of how the stimulation is temporally delivered.Intrinsicstructureoftheneuronalnetworkscanbeuti- lizedtomaximizetheeffectofstimulation.

4.2.1. Open-loopinterventions

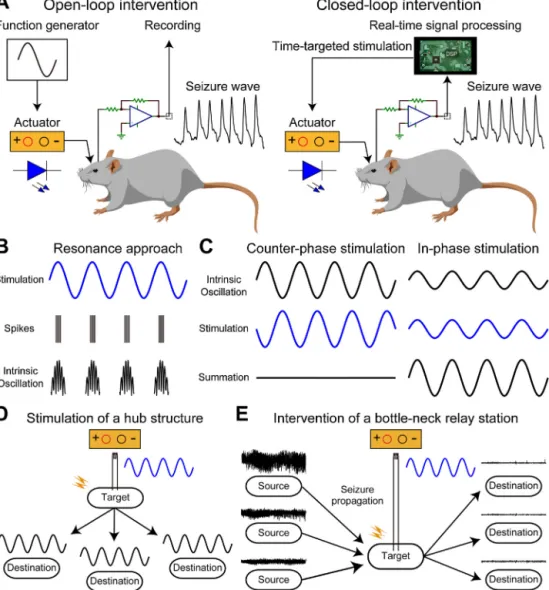

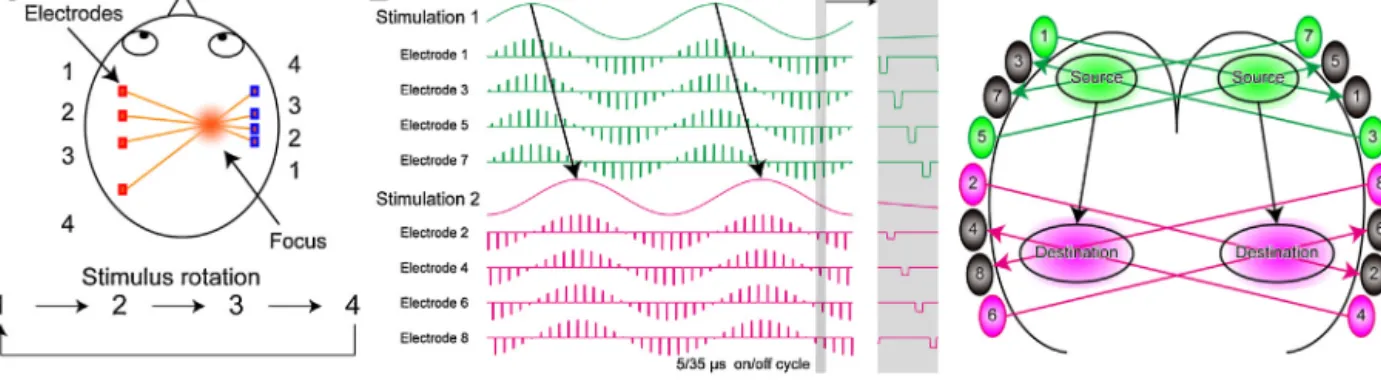

Open-loopinterventionintheoscillotherapeuticcontextmeans introductionofexternalstimulationwithoutthefeedbackofinter- nal oscillatory activity (Fig. 2A). The external stimuli can be a sinusoidalwaveformorpulsetrains.Theopen-loopintervention canbenon-invasive(e.g.transcranialelectricalstimulation:TES) orinvasive(e.g.DBS).Theopen-loopstimulationwithasinusoidal stimuluswaveformcaninteractwithongoingintrinsic network activitiesifappropriatestimulusintensityisprovided(Fig.2B).For example,transcraniallyappliedalternatingelectricalstimulation canmodifyandentrainthemembranepotentialsofcorticalneu- ronsinrats(Ozenetal.,2010).Furthermore,intenseTESat1Hz sinusoidalwavecanphase-specificallyenhancealpha-bandactiv- ityintheparietalcortexofhealthyhumansubjects(Vöröslakos etal.,2018).Ifproperlyapplied,theseresonanceapproachescan modulatethecognitivefunctionsofhumans(e.g.enhancementof memory)(Hanslmayretal.,2019;ReinhartandNguyen,2019).The continuousapplicationofhigh-frequencypulsetrainstotheSTN andtheanteriornucleusofthethalamus(conventionalDBS)suc- cessfullyimprovedsymptomsofPDanddrug-resistantepilepsy, respectively(Deuschletal.,2006;LiandCook,2018).However, open-loopinterventionsarelessflexibleintermsoftemporalstruc- turecomparedwithclosed-loopinterventions,whicharediscussed below.

4.2.2. Closed-loopinterventions

Closed-loopinterventionsforoscillotherapeuticsarebrainstim- ulationsbasedonintrinsicphysiologicalsignalfeedback(e.g.LFP, EEG)(Fig.2A).Thefeedbackinformationallowsthestimulationto betime-targetedandon-demandstimulation.Italsoavoidsover- stimulationandpreventsunwantedout-of-phaseinteractions.

Closed-loopstimulationcanreducethesideeffects ofexces- siveandunnecessarystimulusdelivery.Chronicstimulationina non-responsive,open-loopmannermaybeunnecessarilyexces-

Fig.2.Brainstimulationtechniquesforinterveningwithpathologicaloscillations.

(A)Schemasofopen-loopandclosed-loopinterventionswithepilepticseizures(pathologicaloscillation).Open-loopinterventionprovidespre-determinedstimuluswave- formswithoutprocessingrecordedbrainactivities(e.g.EEG).Recordedbrainactivitiesforclosed-loopinterventionareprocessedinrea-time,andtheparametersofstimulus waveforms(timing,intensity,frequencyetc.)aredeterminedonline.(B)Aschematicshowingofsinusoidalstimulationinanopen-loopmannerandthetypicalresponsesof neuralfiringandintrinsicoscillations.Neuralfirings(spikes)andintrinsicoscillationsareentrainedtotheexternallyappliedstimulusfrequency(resonanceapproach).(C) Conceptualexamplesofclosed-loopinterventionsforthedestructionandrestorationofintrinsicoscillations.Counter-phasestimulation(e.g.electricalstimulation)provides theoppositeeffectofintrinsicoscillationtodestroyanarbitraryoscillation.Incontrast,in-phasestimulationcanrestoredecreasedoscillationbyenhancingthesummation ofintrinsicoscillation.(D)Astimulationstrategyforprovidingawidespreadoscillatoryeffectexternallybystimulatingatargetbrainstructurethatprovidesdiffuseaxonal projectionswithfastsynaptictransmissions(e.g.themedialseptum).(E)Astimulationstrategyforinterveningwithahugeinternaloscillation(e.g.epilepticseizures).

Stimulationofabottleneckstructure(chokepoint)oftheinternaloscillationcaneffectivelyintervenewithit(e.g.theentorhinalcortex).

sive. Unnecessary stimulation can introduce adverse effects by disturbingphysiologicaloscillationsinthebrainbothbyspatialon andofftargeteffects.Forexample,chronicstimulationoftheHPC maydisruptnormalphysiologicaloscillationandtherebycognitive functionsincludinglearningandmemory.Continuousstrongelec- tricalstimulationonthescalpcanintroducepainsensationsvia peripheralnervestimulation.Inaddition,chronicelectricalstimu- lationofthelimbicstructures(includingtheHPCandAMY)could inducepro-seizure effects called kindling (McIntyre and Gilby, 2009).Importantly,anexcessivecontinuousstimuluscouldinduce acceleratedhabituationorreboundsymptomsinpatients(Pilitsis etal.,2008;Shihetal.,2013).PatientsinstructedtoturnonDBSin anon-demandmannerforessentialtremorhadlongereffectsthan open-loopcontinuousstimulation(Kronenbuergeretal.,2006).

Closed-loopstimulation couldintroduce much higher thera- peuticeffectsforneurologicalandpsychiatricdisorders.Thefirst closed-loopconfigurationis‘closed-loopresponsive’stimulation, inwhichpre-determinedstimuluspulsesaredeliveredonlywhen

thestimulusis necessary(on-demandstimulation).Inthis con- figuration, physiological signals are continuously monitoredto automaticallytriggerstimulation inanon-demandmanner.For on-demandcontrolof epilepticseizures,we have revealedthat transcranial applied electrical stimulation triggeredby electro- graphicallymonitoredseizurescaneffectivelyshortentheduration of petit malseizures in rats(Berényiet al., 2012).The closed- loopseizuresuppressionremainedeffectiveatleastformonths (KozákandBerényi,2017).Responsiveneurostimulation(theRNS system)isapprovedforhumanapplicationbytheU.S.Foodand Drug Administration (FDA) as an adjunctive therapy for medi- callyintractablepartialseizurepatients(Morrell,2011).Seizureor seizure-predictingneuronalactivityismonitoredviadepthand/or subduralstripleadsandelectricalstimulationisdeliveredthrough theseleadsinanon-demandmannerintheRNSsystem.Forexam- ple,HPCandcorticalactivitiesaremonitoredandintervenedvia the depthand strip leads, respectively. Closed-loop responsive stimulationcanbecontrolledbybehaviouraloscillationsaswell.