FOREIGN CURRENCY LENDING IN HUNGARY

A LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF FOREIGN CURRENCY LENDING

Edited by Dr. Balázs Bodzási

FOREIGN CURRENCY LENDING IN HUNGARY

A LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF FOREIGN CURRENCY LENDING

Edited by Dr. Balázs Bodzási

Corvinus University of Budapest Budapest, 2019

The studies published in this volume summarise the results of the research carried out within the framework of the Financial and

Economic Center of Corvinus University of Budapest.

Edited by Dr. Balázs Bodzási

Publishing Coordinator:

Krisztina Székely

ISBN 978-963-503-777-3 ISBN 978-963-503-778-0 (e-book)

The publication of the volume was supported by the Ministry of Justice

Ministry of Finance

Publisher: Corvinus University of Budapest Budapest, 2019

Printed by Komáromi Nyomda és Kiadó Kft.

Manager: János Ferenc Kovács managing director

Szerkesztette: Dévényi Kinga

Szerzők: Csicsmann László

(Bevezető)Dévényi Kinga

(Iszlám)Farkas Mária Ildikó

(Japán)Lehoczki Bernadett

(Latin-Amerika)Matura Tamás

(Kína)Renner Zsuzsanna

(India)Sz. Bíró Zoltán

(Oroszország)Szombathy Zoltán

(Afrika)Zsinka László

(Nyugat-Európa, Észak-Amerika)Zsom Dóra

(Judaizmus)Térképek: Varga Ágnes

Tördelés: Jeney László

A kötetben szereplő domborzati térképek a Maps for Free (https://maps-for-free.com/) szabad felhasználású térképek, a többi térkép az ArcGIS for Desktop 10.0 szoftverben elérhető Shaded Relief alaptérkép felhasználásával készültek.

Lektor: Rostoványi Zsolt

ISBN 978-963-503-690-5

(nyomtatott könyv)ISBN 978-963-503-691-2

(on-line)Borítókép: Google Earth, 2018.

A képfelvételeket készítette: Bagi Judit, Csicsmann László, Dévényi Kinga, Farkas Mária Ildikó, Iványi L. Máté, Muhammad Hafiz, Pór Andrea, Renner Zsuzsanna,

Sárközy Miklós, Szombathy Zoltán, Tóth Erika. A szabad felhasználású képek forrását lásd az egyes illusztrációknál. Külön köszönet az MTA Könyvtár Keleti Gyűjteményének

a kéziratos oldalak felhasználásának engedélyezéséért.

Kiadó: Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem

A kötet megjelentetését és az alapjául szolgáló kutatást a Magyar Nemzeti Bank támogatta.

CONTENT

Preface 7

Balogh László:

The fifteen years of foreign currency loans in Hungary

(Launch, management and international background) 9

Becsei András:

It’s all about timing – On the conversion of foreign currency based loans 29 Berlinger Edina:

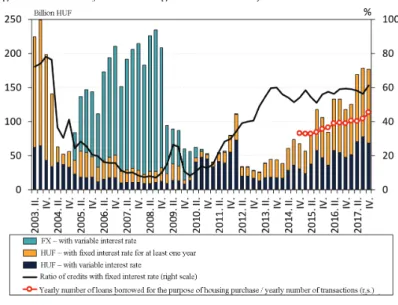

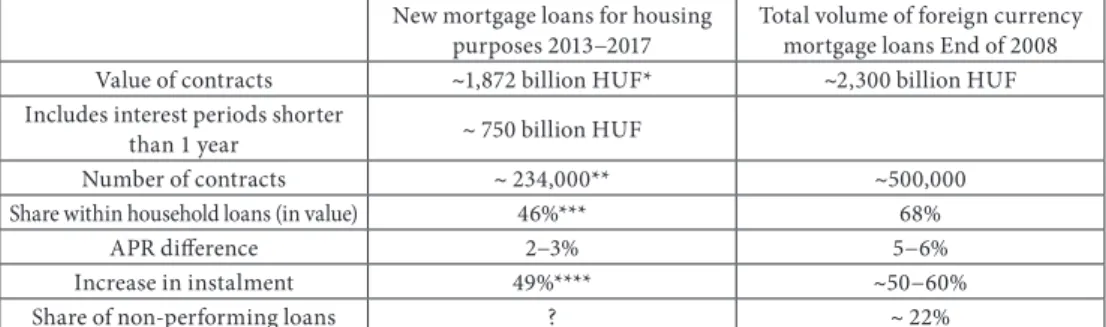

The risks of variable interest rates: A case study of mortgage lending

in Hungary from 2004 to 2018 35

Bodzási Balázs

Legislative steps in Hungary to address issues connected

with foreign currency-based consumer loans 55

Dancsik Bálint – Fábián Gergely – Fellner Zita:

The conditions for the emergence of foreign currency lending

– causes and effects 91

Dancsik Bálint – Fábián Gergely – Fellner Zita:

Beyond finances: why do non-performing households not pay? 117 Dömötör Barbara:

The Hungarian ”Big Short”. Rational and irrational reasons for

the spread of foreign currency loans 141

Korba Szabolcs:

Retail foreign currency lending and the economic crisis –

juridical experiences 157

Kuti Szilvia:

The consequences of the dramatic spread of transactions connected

to foreign currency lending in the daily life of notaries and the ’reparation’ 209 Lajer Zsolt:

Experiences of defendants in lawsuits related to foreign currency loans 245 Landgraf Erik:

Legal experiences of retail foreign currency lending 2004-2010 271

Martonovics Bernadett:

Examination of enforcement issues related to consumer credit agreements 305 Rezessy Gergely:

The property market and macroeconomic factors of foreign exchange

lending, as well as its comparison to the current credit cycle 323 Tebeli Izabella:

Increased focus on financial consumer protection in stressful situations

caused by foreign currency loans 347

Vezekényi Ursula:

On the legal issues and lessons learned from litigation related to consumer

currency-based lending 373

Walter György:

The development of corporate and project foreign currency loans

and their risk in Hungary 405

Zsolnai Alíz:

Lending in foreign currency from the regulator’s aspect 421

Appendices 437

PREFACE

During the 19th and 20th century, the Hungarian society experienced many upheavals.

There is one substantial common element in these historically traumatic changes: all of them were affecting the approach of Hungarian society towards property.

As a result of the Revolution and Freedom Fight of 1848-1849 feudal ownership was abolished and civil private ownership was born. The fact that development of civil society and modern private ownership could only take place under the Austrian rule was one tragic event of Hungarian history in the 19th century. This also gives an explanation to the impact of Austrian private law that lasts to this day.

Although after World War I, this development was already within the framework of an independent Hungarian state, however the Hungarian state that became independent again was a country with a significantly mutilated area and economically converging to bankruptcy in 1920. Another historical tragedy was the development of the communist dictatorship and the almost total abolishment of private property after World War II.

The own property of the Hungarian population was practically limited to properties that provides for housing. It is no coincidence therefore, that Hungarian society has developed a very close link towards residential real estate and the agricultural land following the traditions of the former archaic peasant society. The consequence of the above is the high percentage of homeowners in Hungary, which is also outstanding in European comparison.

Hungarian people have always preferred wholly owned apartments against renting a home. This only has been intensified after the change of regime, when private property was once again recognized.

As the demand of the people for owning real estate property has remained unchanged for decades, the political leadership had to take it into account both after 1945 and after the change of regime. Means by which the housing stock could be increased and the desire of the Hungarian people to own apartments could be met were necessary to be found.

This has become a traditional tool for state-supported housing loans. It has already appeared in socialism, and, became a popular tool again after the economic recession of the 1990s at the turn of the millennium, by which the number of new housing constructions has risen over 40,000 again. This demand and tendency had to be taken into account by the governments after the political change in 2002. However, a decision of switching from domestic retail lending to foreign currency lending was made, instead of state support, for various reasons. This volume intends to present, inter alia, the consequences of this step.

In Hungary, retail currency lending has become one of the major economic, legal and partly social problems of the 2000s. Many studies, articles and volumes have already dealt with the causes and consequences of its development and spread. I would like to refer to only one of those works: a multi-authored volume of studies edited by Professor Csaba Lentner in 2015 (The Great Handbook of Foreign Currency Lending, National Public and School Publisher, Budapest, 2015).

A similar, multi-authored work is now in the hands of the Reader. In the background of the idea of publishing such a volume was the fact that by 2018 the crisis caused by foreign

currency lending was largely over, most of the issues raised were resolved. Naturally, there are still pending trials before domestic and European judicial forums and, unfortunately, there are still enforcement procedures related to foreign currency loans.

Part of the society was seriously affected by the drastic weakening of the forint exchange rate, after 2008 and for some the significant rise in real estate prices in recent years has not solved their problems with foreign currency loans.

However, the situation of many debtors has been resolved and nothing could demonstrate better that this crisis is behind the country, from the point of view of the national economy, than the fact that retail mortgage lending has begun to show huge growth rates again for years. This means forint loans, of course. At the same time, however this also carries potential risks, therefore it is worth summing up the lessons learned from foreign currency lending.

The volume comprises the work of eighteen authors. As an editor, I found it important to compile an authorship that involves both economists and lawyers. I was looking for "witnesses’

who came into direct contact with this "banking product" from banking or a regulatory or a legislative point of view. On the one hand, these are professionals who have seen how retail currency lending was spreading and becoming a threat to the entire Hungarian economy, directly from the beginning of the 2000s, and on the other hand, professionals who had an active role in the legislation when dealing with this issue, after 2010 and 2014.

I would like to use this opportunity to express my gratitude for your work.

The volume is quite colorful: many authors, multiple points of view. As an editor, I obviously do not agree with all the positions, but I considered it important to try to capture these differing opinions. Let us show what these professionals thought about the events of 8-10 years ago, in 2018.

Whoever was right will be determined by the Reader or the events of the coming years.

Capturing a decisive segment of the last 15 years period of the Hungarian history in a scholarly and objective manner as far as possible, is what was important to me. Hopefully this goal has been achieved.

Budapest, 7 May 2019

Dr. Balázs Bodzási editor

Deputy State Secretary, Ministry of Finance

THE FIFTEEN YEARS OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE LOANS IN HUNGARY

(LAUNCH, MANAGEMENT

AND INTERNATIONAL BACKGROUND)

1. International outlook, genesis

Foreign currency lending is not an unknown phenomenon either in Europe or outside Europe.

Some examples of foreign currency lending were already known before the European currency loan crisis, both in the developed world (Australia) and in developing countries (Mexico). The reason why foreign currency lending is attractive is quite simple: the interest rate difference between the national currency and the foreign currency is so large that a loan denominated in a foreign currency seems to be more favourable to the borrower (and the key word here is seems) than the same loan in the national currency. This phenomenon is usually coupled with higher inflation in the home country, while the inflation rate in the country of the foreign currency is relatively low. The trap is the prevailing exchange rate risk associated with the foreign currency, particularly for longer-term loans.

In Europe, the FX loans first emerged in Austria in the mid-1990s, mainly in areas of the country near the Swiss border. Austrian commercial banks found that local residents (and entrepreneurs) were happy to drive 15−20 km to a bank on the Swiss side of the border to take out a loan in Swiss francs (CHF), rather than in Austria in the local currency, due to the 1.5 per cent to 2 per cent in- terest rate difference. In response to this competitive challenge, some Austrian credit institutions included Swiss franc loans in their credit product portfolio. The product soon became available all over Austria and quickly became popular; in 2005 around 30 per cent of the total residential loan portfolio already consisted of this type of loan. This was the beginnings of one of the most dangerous

“financial time bombs” of the 21st century, which later caused major problems in the Central Eastern European region, even becoming a systemic risk factor in some countries, primarily in Hungary.

How can it be explained how foreign currency lending in the 21st century, started in Central and Eastern Europe, expanded at such an extremely fast pace? This was basically caused by three factors:

a. The establishment of foreign, typically Austrian and Italian banks in the Central and Eastern European market as part of the local privatisation process;

b. high inflation and high interest rates in the transforming Central and Eastern European region converging with the Western European economies;

c. in some cases, a spectacular offensive tool of foreign controlled banks to increase their residential market share in the banking sector, as opposed to local banks with poor FX resources.

Figure 1: Share of foreign banks in EU Member States (June 2011)

Source: Consolidated Banking Data, Statistical Data Warehouse, ECB

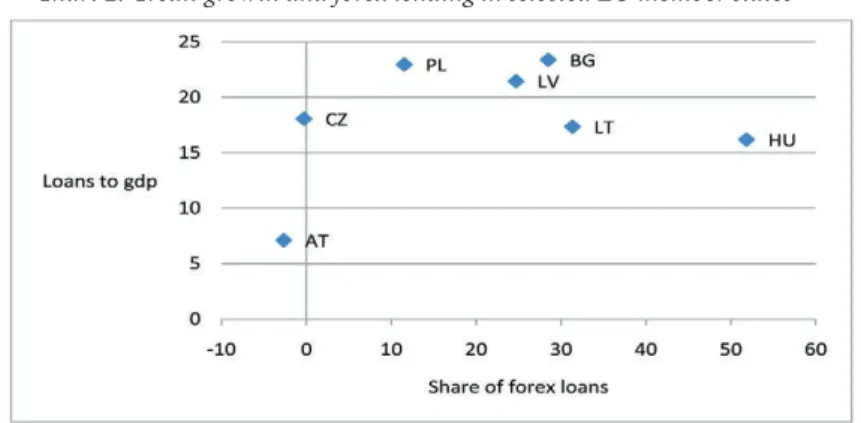

Following the Central and Eastern European privatisation process in the 1990s, a consequence of the establishment of Western European banks in these markets was that, after taking up their positions in corporate lending, they sought to expand their activities to the residential segment as well. For these foreign banks, the most spectacular method of market share acquisition (from the perspective of the banks) from the 2000s was residential foreign currency lending denominated in FX. This was mainly due to the fact that foreign parent institutions had an abundance of resources and liquidity in FX, which they happily shared with their Central and Eastern European subsidiaries. Affiliate banks were able to use those FX resources in the residential segment with a very high margin, and they were able to acquire significant parts of the market even from the best-known local players (OTP, or Pekao in Poland) since the local players were not in a good position in respect to their FX funding potential. This was true for Poland, Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria, Serbia and Hun- gary. This phenomenon is clearly demonstrated by the capital flow to the banking sector of these countries at the time. There is a clear correlation between the credit expansion of the 2000s and the amount of capital inflow.

Chart 2: Credit growth and forex lending in selected EU member states

Source: Balance Sheet Items, ESA95, Statistical Data Warehouse, ECB

Figure 3: Forex borrowing of households and non-financial corporations in EU Member States (February 2011)

Source: ECB, ESRB

Foreign currency lending is not specific to Hungary but is a typical phenomenon of the entire Central and Eastern European region, including Austria. However, albeit to a lesser extent, foreign currency lending also emerged in countries that did not adopt the euro such as Denmark and Sweden.

A distinction must be made between residential and corporate foreign currency lending.

Through the export of goods or services, many companies can generate regular income in foreign currencies, so the repayment of a loan in a foreign currency is less problematic for them as part of their standard business operations. In contrast to this, the overwhelming majority of the population generate their income in local currency, but their liabilities may still be denominated in a foreign currency. Closely related to this fact is that a change in the exchange rate risk increases both monthly payments and the total amount of remaining debt. While some companies are able to properly handle this kind of exchange rate risk, ordinary people are typically not prepared for it.

The specificity of the Hungarian situation is that the volume and proportion of residential foreign currency lending (more precisely, its disproportionateness) was so high that it initially led to a systemic financial risk, and then to a societal risk. At a professional and decision-making forum of the ESRB (European Systemic Risk Board − European System of Financial Supervision), I described the situation as follows: “In Hungary FX lending has become a systemic risk issue, but it has continued to slowly grow into a public policy question”. The ESRB agreed with this opinion in every respect.

So the Hungarian specificity was that the proportion, volume and rate of growth of foreign currency lending were extremely high compared to any other European country, which not only became a risk in the banking system but also a general societal issue.

The expectations in many countries of the region before EU accession are rarely talked about now, but they were an important factor in the 2000s, and in many countries there were also political promises in anticipation of imminently joining the euro zone. This actually took place in Slovenia and Slovakia, then, a short period later, in the Baltic States, but it did not happen in Hungary and Romania. However, the approach of banks and the expectations of the population may have been rational by offering and taking loans for 15 to 20 years in the hope that the country would adopt the euro within a few years.

Note, however, that this argument would have been valid only if the currency of the loans had been the euro, rather than CHF. Nevertheless, it seems to be clear that foreign currency lending has not led to any significant and long-term problems in countries that have since joined the euro zone.

Foreign currency lending, which has become widespread in the Central and Eastern European region, has some common features in these countries: foreign currency lending emerged as a phenomenon in every country where loans with more favourable interest rates could be provided due to the interest rate difference between the national and foreign currencies. It is safe to say that the main driver of foreign currency lending was the significant difference between the interest rates of the two currencies.

Another conclusion to be drawn is that the business environment, the legal framework, and the different cultures of financial institutions could in some cases result in solutions with less damaging consequences. This might be the reason for the different weight, proportion and extent of problems of foreign currency lending from one country to another. In saying this, I have no wish to down play the problems of foreign currency lending in Poland, Croatia or Romania, but, precisely due to some specific factors, its extent and severity was far from that in Hungary at the time when the 2008 financial crisis broke out.

2. The macroeconomic environment in Hungary and other factors leading to foreign currency lending

Following the change of government in 2002, there were two fundamentally new, almost unexpected, dramatic macroeconomic developments: the budget deficit, which had been decreasing dynamically until then and was already close to the 3 per cent level, increased considerably, reaching 7 per cent, and then 9 per cent. The high budget deficit led to serious inflationary pressures. The National Bank of Hungary (hereinafter MNB), which had just shifted to a system of inflationary targeting, was forced to increase the key interest rate from 6.5 per cent to 12.5 per cent within a short space of time. Obviously, this base rate increase of 600 basis points had a direct and drastic impact on the private housing HUF loans granted by commercial banks. Almost in parallel with that, the Medgyessy Government abolished the interest rate subsidies on housing loans, introduced by the first Orbán Government.1

Figure 4: Budget balance and current account

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Central Bank of Hungary

Thus, as a result of the increase in the base rate and, almost simultaneously, the abolishment by the Medgyessy Government of the interest-rate subsidy mechanisms introduced by the previous Government, the actual level of the interest rates of long-term (HUF) loans for housing construction increased to 15-18 per cent. It was obviously not a rational decision for potential loan recipients to become indebted for 10 to 15 years or even longer at this interest rate.

A vacuum was created in the market as banks could not provide loans in HUF at a lower inte- rest rate, but no one wanted to become indebted at this interest rate for 15 to 20 years. This was the

1 Two housing subsidy programmes were running during the Orbán Government: interest rate subsidies on loans financed with mortgage deeds and additional interest rate subsidies. Without describing the system in detail, let me just point out that the maximum interest to be paid by the borrower fell to 6 per cent in autumn 2001. The sytem was succesful: Banks provided mortgage loans amounting to 493 billion HUF in 2002 and as much as 825 billion HUF in 2003.

vacuum that was filled by foreign, mainly Austrian, banks already present in the domestic market from 2003 or 2004, which introduced euro- (EUR) and Swiss franc- (CHF) denominated loans into the domestic retail market. The nominal interest rate of such foreign currency loans was 3-5 per cent.

At that time, there was abundant liquidity in Western Europe, and it seemed to be an exciting and attractive idea for bank managements to bring the CHF product, already tried and tested in Austria, to the Central and Eastern European region, where the western margin could almost be doubled. This was another method for them to take advantage of the opportunity of profit maximisation offered by the abundance of liquidity.

Prior to the emergence of foreign currency loans, OTP dominated the Hungarian market for private housing loans. Together with cooperative savings banks, OTP had a market share of nearly 80 per cent. Unexpensive funding in contrast to foreign banks, OTP and cooperative savings banks did not have a cheap source of foreign currency for the introduction of EUR and/or CHF products. This means foreign banks wanted to take advantage of the situation created by additional inadequate economic policies not only for profit maximisation, but also to acquire an actual market share. This could help them to reduce the market share of Hungarian banks, and thus gain a larger segment of the Hungarian market for themselves.

And they succeeded: Following the introduction of CHF products, by 2007, the combined market share of ERSTE, Raiffeisen, Unicredit (Bank Austria) and other foreign banks (e.g.

CIB) increased spectacularly, mainly was funding of OTP. Although, after a while, OTP was forced to enter the competition with CHF products, foreign resources were much more expensive for them than for their foreign-owned competitors.

Figures 6 and 7 perfectly illustrate that foreign banks used the vacuum created by the extremely high interest rates of HUF mortgage loans quite deliberately and aggressively to actively increase their market share by providing CHF-denominated loans. Between 2003 and 2010, their loan portfolio increased nine-fold, and the amount of CHF-denominated loans rose from zero to HUF 3,200 billion. Simultaneously, the market share of foreign-owned banks in the market of residential loans increased from approx. 28 per cent to almost 60 per cent during the same period.

Figure 5: Expansion of foreign banks on the Hungarian household loan market (billion HUF)

Figure 6: Share of foreign banks on the Hungarian household loan market

Because the sale of CHF credit products was extremely profitable for banks, it took place amidst ever fiercer competition. Furthermore, foreign currency-denominated cre- dit products were increasingly sold through the intermediation of credit agents, often very aggressively. Due to short-term profit interests and high commissions, the sale of credit products was not only aggressive, but also often coupled with misleading, or even deceptive, sales practices. Therefore, CHF mortgage loans were taken out by a large number of people even if they did not really need them. Moreover, those who actually needed such loans for housing purposes could hardly find anything else in the product portfolio of banks in 2005 other than CHF-denominated mortgage loans. Lending conditions were gradually eased, and the loan-to-value ratio required by banks became increasingly lower, while the rules covering borrowers’ income became increasingly lax, and in some cases were even abolished altogether. Worthy of note is a well-known advertisement by one of the commercial banks.

The bank’s advertisement stated: "… We do not care how much you earn, we are only interested in the value of your property!" The methods of irresponsible lending by banks at that time could hardly be better illustrated.

The profit level of mortgage loan products for housing purposes was so high that the affected banks soon entered the market with their Swiss franc-denominated home equity loans as well. This new credit product was used by many borrowers to buy consumer goods or to travel abroad. The aggressive and misleading sale of bank loans tempted consumers, who otherwise did not want this type of loan, even more aggressively to pledge their residential properties, and on a CHF basis.

Looking back, the question seems to be justified: where were the risk managers of banks? How could the internal risk management rules of that time allow bank managers to approve such loans under the principle of prudent lending? The absurdity of the issue is also illustrated by the fact that the mortgage loan, which had been used for decades as a product for the purchase of residential properties, was transformed into a credit product for luxury or premium consumption. As early as 2008, 70 per cent of residential mortgage loans were already being used for consumer goods. This clearly indicates the degree and irresponsibility of competition between banks in the residential market and the extent to which borrowers were unprepared and deceived when they pledged their residential properties for premium consumer items or any other purpose not related to housing.

Furthermore, the CHF schemes developed in the field of car financing, which had been used in Hungary since the late 1990s, also posed serious prudential and consumer risks. In international practice, car financing typically requires an own risk of 30-50 per cent, and the loan for the remaining amount is provided for 3 or a maximum of 5 years. Hungary was first characterised by car loans without an own risk, and then those were provided for 7-10 years. This scheme can hardly be regarded as prudent from a financial point of view because an 8- 10 year-old vehicle cannot provide realistic coverage due to its loss of value over time.

3. Regulatory issues, response from the authorities, or the lack of it

During the period concerned, between 2004 and 2009, there was practically no action by the authorities, regulation or supervisory intervention whatsoever in Hungary in favour of consumers. As a rare example, the 2003 Annual Report of the Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority (HFSA) drew attention to the prospective risks of foreign currency lending, which was insignificant at the time (3 per cent) but had alarming dynamics.

However, the political response was clear: In the first half of 2004, the HFSA was transformed through an infamous act called Lex Szász, and the entire management of the financial supervisory authority was dismissed. The independence of the supervisory authority, previously guaranteed by law, was circumvented by abolishing the position of the president in the authority and creating a new decision-making body (the Supervisory Board). Unlike its predecessor, the new supervisory authority is a declared government agency, reporting quarterly to the Minister of Finance, who is also entitled to provide guidance to the financial supervisory organisation.

Today, there is extensive literature on the reasons why the state, i.e. the HFSA, the MNB and the Ministry of Finance, did not intervene between 2004 and 2010, and why they did not keep the dynamically expanding market of private housing foreign currency lending under control. Several questions have been raised, such as: why they did not require more stringent risk management and stronger financial consumer protection, and why did they not incorporate adequate income and coverage standards into the system to control the huge volume of risk?

The responses of the actors of the time are mostly limited to claiming that neither the supervisory authority nor the MNB had the legal means to stop or ameliorate the process.

This is, of course, only the partial truth. Nothing actually prevented the Government from setting more stringent coverage requirements or prescribing stricter checks of income in financial legislation. The supervisory authority could have set a higher capital requirement for this type of loan, making such loans more expensive and more prudent. The MNB, on the other hand, could have specified standards for the mandatory reserves of banks. However, such measures were not implemented. I will come back to the reasons later.

The alleged lack of means can be refuted with the abolishment of yen loans. In addition to EUR and CHF, Japanese yen-denominated mortgage loans also emerged, mainly in the product range of two banks. The Japanese yen was at that time characterised by significant

volatility, as well as by rapid and abrupt exchange rate fluctuations, so the response threshold of the MNB experts and the supervisory authority had already been reached by this phenomenon. A few months after the introduction of the product, the banks concerned discontinued the disbursement of yen-denominated mortgage loans in response to the (non- legal) joint action of the supervisory authority and the MNB. This fact also indicates that, if there had been sufficient recognition and will after 2004, the MNB and the HFSA could have easily decelerated the rapid proliferation of CHF loans and could have applied the brakes at any time. As we know today, they did not.

The question therefore arises, what could the reason for the “laissez-faire, laissez-passer”

approach adopted and maintained until 2009. When seeking an answer to this, the start- ing point should be the fact that the performance of the Hungarian economy at the time of the rise of foreign currency loans was miserable: From 2006, economic growth had started to slow down sharply. This fall was so drastic that GDP grew by only 0.4 percent in 2007 and 0.9 per cent in 2008. At that time, there was still no sign of a crisis in Europe; quite the opposite: the money market sentiment was buoyant, there was an abundance of money in the markets, and world trade was soaring. Even the slightest deceleration of the domestic credit market, which was still growing rapidly, could have had a boomerang effect, mainly in the construction industry. In that period, the Hungarian construction industry − precisely as a result of dynamic lending − produced 35 to 40 thousand new homes annually. The deceleration of lending would clearly have led to an almost immediate fall in GDP growth, which was already quite low. Obviously, because the crisis emerging in autumn 2008 had not been anticipated by anyone in Hungary (and even those who anticipated it said that, “only the side wind of the crisis of the west will affect Hungary”), all the decision-makers wanted to keep GDP stable. Therefore, there was not the slightest intention to decelerate, or even to exercise stronger control over domestic foreign currency lending, which was growing dynamically and posed increasing risks.

Another dilemma also needs to be mentioned. It is frequently asked why the Hungarian population became indebted in CHF. Or, more precisely: why Hungarian banks granted their loans in CHF (and not in EUR)? The answer on the behalf of banks is clear: due to the different levels of inflation, CHF loans could be sold at a nominal interest rate of 1.5-2 per cent below that of the same loan in EUR. Obviously, this seemed to represent a more attractive option for those borrowing housing loans. Fierce market competition and the all-important pressure to increase market share forced banks and credit intermediaries to exploit even the slightest short- term advantage. The Hungarian economy was linked to the euro and the euro zone in myriad ways already by the 2000s, and until 2006 political actors also continued to make promises that the euro would soon be introduced. It was precisely after the huge budget deficit of over 9 per cent in 2006 that the then president of the MNB declared at a conference in Vienna that Hungary had little chance of joining the euro zone before 2014.2 There were countries such as Croatia, where banks, and the public, adopted a more rational approach, and, in addition

2 Of course, Zsigmond Járai, the then president of the MNB, did not anticipate the imminent financial crisis and the resulting crisis of the euro-zone, which lasted for many years.

to CHF lending, EUR lending was also significant. The irrationality of CHF lending is also illustrated by the fact that, although the MNB had considerable foreign exchange reserves at that time, the reserves mainly consisted of EUR and, to a lesser extent, USD. However, they contained no CHF at all. In other words, the MNB actually failed to provide coverage for a serious exchange rate risk in the event of an emergency.

From time to time, the question is raised in the media, and partly also in the literature:

What is the root cause of the possibility of foreign currency lending in Hungary? The first Orbán Government is often blamed for allowing the emergence of foreign currency loans by closing the foreign exchange liberalisation process and abolishing the last restrictions by law. But the reality is quite different.

When joining the OECD in 1996, Hungary undertook, with a few exceptions, to fully liberalise the regulation of foreign exchange operations by 2001. At the time of the OECD accession in 1996, Hungarian commitments were legally proclaimed by the National As- sembly. Hungary was also obliged to take this foreign exchange liberalisation measure due to its imminent EU accession. This resulted in the annulment of the previous foreign exchange act in 2001, which automatically enabled a number of foreign exchange operations, including the provision of residential foreign currency loans.

The elimination of previous legal constraints led to the same degree of liberalisation of current and capital operations as in other EU and OECD Member States. Accordingly, it would not have been possible to either prohibit or prescribe a separate licence for foreign currency lending due to both OECD and EU regulations. It is no coincidence that the problem of foreign currency lending was by far not limited to Hungary in the 2010s, since several other EU Member States were also affected. This does not of course mean that it would have been impossible to decelerate, or even stop, the proliferation of foreign currency lending by various prudential and other means when the volume of foreign currency loans and the associated risks reached a level that was already dangerous for the national economy.

4. Some Hungarian peculiarities of foreign currency loan contracts

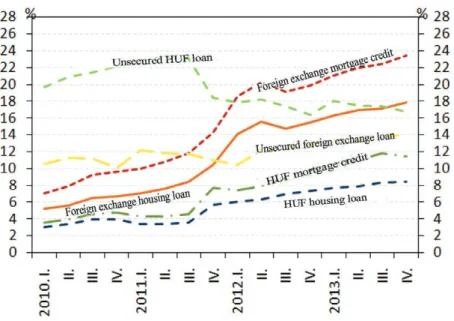

One of the peculiarities of contracts related to foreign currency-denominated mortgage loans was that they allowed banks to alter interest rates and other charges unilaterally. This feature increased the dominance of banks in an already highly asymmetric bank-customer relationship. As a result, on the one hand, consumers (households) were exposed to an increase in payment due to exchange rate fluctuations, and, on the other hand, to a unilateral modification of contractual terms by banks. Several unilateral increases in interest rates also played a significant role in the increase of payments in the case of long-term mortgage loans.

In 2005 to 2006, clients already typically took out loans above an annual percentage rate (APR) of 6-7 per cent. This included a surcharge of about 5 per cent by banks compared to the CHF reference rate (CHF LIBOR). In the case of contracts already signed, banks unilaterally increased the APR by another 2 per cent to 8-9 percent during the crisis, thus significantly increasing monthly payments.

Figure 7: Annual percentage rate (APR) of a typical Swiss franc-based mortgage loan in different scenarios

Source: MNB (Central Bank of Hungary)

Another peculiarity of Hungarian foreign currency lending was that banks used different selling and buying rates of exchange for the disbursement and for the repayment of loans.

This can also be explained by the dominant position of banks. As a result, the banks realised some additional exchange gain when the loan was repaid by the borrower. They were allowed to do so until the end of 2010. However, in autumn 2010, the new Government prohibited this practice, requiring banks to use the medium rate.3

5. Recognising the problem, moving towards solutions

It was only after the outbreak of the crisis in 2008 that decision-makers first recognised the close connection between the problem of foreign currency lending and the crisis of the economy, more specifically a significant increase in unemployment and changes in the situation of borrowers (e.g. job losses). All this represented a serious credit or repayment risk, a part of which had already been realised. For reasons already mentioned above, the payments borrowers had to make were constantly increasing, just like the difference between foreign exchange rates, and banks used higher and higher interest rates (surcharges). An increasing number of borrowers were unable to pay the ever-increasing monthly payments, because the incomes of their families also fell significantly. This was the time when policy- makers actually directly faced the enormous risk of foreign currency lending accumulated over the years, as well as the serious challenges to families, which resulted in a spectacular increase in the rate of problematic loans and, even more, non-performing loans. Non- performing loans represent a problem for banks, or even the entire banking system, as they require special provisions, which significantly lower their profit levels.

3 In contrast, in Serbia only the medium rate could be used for both the provision and the repayment of the loan.

Problems gradually became more than just banking difficulties. Within a very short space of time, non-paying families fell into a situation where mortgage enforcement, or even eviction, already posed a real threat to them. The more such individual, family problems there were, the more obvious it was that all this would lead to social tensions, which needed to be handled by the authorities in some way.

In 2009, it was recognised that there was no institution or authority in Hungary that could take legitimate action for the protection of financial consumers in order to handle the vulnerability of consumers created by foreign currency loans. Basically, the legislative bodies authorised the Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority by providing a legislative mandate for prudential supervision and the supervision of financial market processes (market surveillance). Until the outbreak of the crisis, supervisory authorities were traditionally responsible for the stability of the financial system and institutions. At that time, such bodies did not have express authority over financial consumer protection in Europe. It was the crisis that led to a situation where financial supervisory authorities received a role in consumer protection. Hungary was one of the first European countries where this change took place.

In 2009, the Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority was completely reorganised, new legislation was passed, the former management left the organisation, and, with one-person management, the supervisory authority now had a President again instead of a collective decision-making body. This decision in itself indicates that the then Government implicitly admitted the operational inability, incapability and incompetence of the former Supervisory Council with respect to recognising and managing the risks of foreign currency lending in a timely manner.

Thus, from 1 January 2010, the Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority was granted consumer protection powers. This was an essential measure for the authority to start to address the issue of foreign currency lending, already affecting the entire sector, and to mitigate the problems of consumers and the population. All of this enabled the authority, sooner or later, to manage the systemic risk, already present at that time, in some form or other.

6. The measures of the new Government, the problems of foreign currency loans from 2010

One of the first measures of the second Orbán Government, established in 2010, was to replace the management of HFSA and to appoint a dedicated Vice President in charge of specific financial consumer protection issues. The first strategic task of the supervisory authority was the assessment of problems and the preparation of short- and longer-term proposals to mitigate the situation. A separate directorate was formed to manage and process consumer protection issues, to examine individual submissions already reaching a magnitude of tens of thousands, and to find solutions. The existing legal framework also had to be examined in the same way. One of the key questions was where brakes had to be applied in the legal environment in effect at that time.

One of the first measures of the Orbán Government was to de facto ban residential mortgage loans. This was not a complete ban de jure as those natural persons who had regular income in

a foreign currency and whose monthly income was at least fifteen times the monthly payment were still entitled to take out foreign currency loans. This condition was of course so strict that only very few private individuals had access to foreign currency loans, and the act actually put an end to the disbursement of new foreign currency loans in Hungary in the summer of 2010.

Incidentally, a total ban would also not have been possible because Hungarian legislation is based on the EU Directive on consumer credit.4 Of course, the prohibition of the provision of new foreign currency loans did not solve the problem in itself, but at least prevented further growth in the volume of loans.

Upon a proposal of the supervisory authority, further legislation was adopted in 2010.5 According to the new law, in the future only the medium rate could be used for the calculation of payments. In addition, the law reduced the prepayment charge, or maximised the charge at that reduced level. The law prescribed a free-of-charge procedure for borrowers able to make a final repayment or a higher-amount prepayment on their loans. As another important element of the law, credit institutions were limited in unilaterally amending their contracts. In this respect, the law stipulated that the credit institution was no longer allowed to change the contract unilaterally to the disadvantage of the borrower. This could only be done in a way that was beneficial to the consumer. Furthermore, borrowers in dire straits were allowed, on a single occasion, to request the extension of their credit contracts for a maximum of five years. The creditor could not deny such a request, and the amendment of the contract was free.

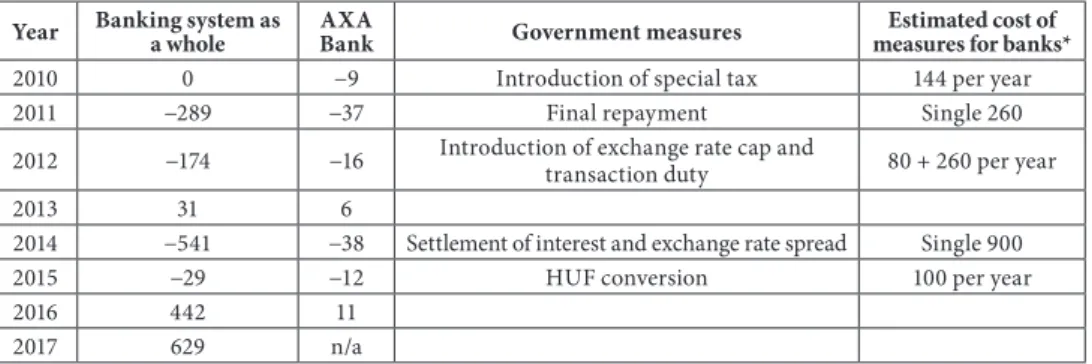

Subsequently, the Government and the National Assembly adopted further measures to mitigate the problem for foreign currency borrowers. In autumn 2011, the final repayment of foreign currency loans was allowed under very favourable conditions. Within a few months, approx. 170 thousand borrowers had exploited this opportunity. The debt thus released was about HUF 370 billion, while the total amount repaid was HUF 1,355 billion. As a benefit for borrowers, it was possible to repay Swiss franc-based debts at a rate of HUF 180, instead of the official CHF exchange rate of around HUF 250. In the case of euro-denominated loans, the foreign currency loan could be repaid at a rate of HUF/EUR 250, while a discounted rate of HUF/JPY 2 was used for Japanese yen. Banks could deduct up to 30 per cent of their resulting losses from the bank tax.

The average amount of repaid loans was HUF 5.8 million, based on the fixed final repayment rate.

Anyone could opt to make a final repayment by 30 December 2011. The availability of coverage for final repayment had to be confirmed by 30 January 2012, and the loan had to be settled by 28 February 2012 at the latest. The measure was all in all successful, significantly reducing both the number of foreign currency borrowers and the volume of foreign currency loans. Nevertheless, it was only a single step in the management of all the problems. On 30 September 2011, there were 750 thousand foreign currency mortgage loan borrowers, compared to only 560 thousand on 31 March 2012. The volume of foreign currency mortgage loans decreased from HUF 5,600 billion on 30 September 2011 to HUF 4,245 billion.

4 Directive 2008/48/EC on consumer credit agreements, transposed into Hungarian law by Act CLXII of 2009 on consumer credit.

5 See Act XCVI of 2010 on the amendment of certain finance-related acts in order to support consumers in a difficult situation due to taking out housing loans (promulgated on 28 October 2010)

A so-called “exchange rate cap” was introduced in September 2011 to mitigate the effects of exchange rate fluctuations. The exchange rate cap was aimed at temporarily dampening the effects of exchange rate fluctuations, so the repayment exchange rate for foreign currency- denominated mortgage loans was fixed for five years. This fixed exchange rate was HUF/CHF 180 for Swiss franc-denominated loans, HUF/EUR 250 for euro-denominated ones, and HUF/

JPY 2.5 for loans denominated in Japanese yen. Borrowers who opted in were also granted debt relief. The interest part of the deferred debts of clients choosing the exchange rate cap was taken on by banks and the state budget at 50−50 per cent. Clients choosing the exchange rate cap were exempted from the payment of interest amounting to approx. HUF 60 billion. About 186 thousand foreign currency borrowers had entered into such contracts by the end of 2014.

According to the legal regulation, after the 5-year fixed period of the exchange rate cap, a further limit was used to protect consumers when including in the payment the amount accumulated as a result of the exchange rate cap, recorded in a separate account. Pursuant to this limitation, the payment could not be increased by more than 15 per cent. In terms of figures, 15 per cent of the average payment (approx. HUF 56 thousand) was not more than HUF 8,400 per month.

In addition, the Government protected borrowers in the most difficult situations with an extraordinary eviction moratorium in effect until 16 September 2015, preventing the auctioning of their residential properties and the loss of borrowers’ homes.

As a result of another government measure, the National Asset Management Company was launched in 2012. The National Asset Management Company was established to help the socially most deprived borrowers. They purchased the property of borrowers for the state, but the erstwhile borrowers could still remain in the property as tenants for rents much lower than the market price. In addition, the creditor banks released the borrowers’ outstanding debts from mortgage loans. The National Asset Management Programme was based on a joint effort by the Hungarian state and the banks. The state supported the purchase of homes with substantial budgetary resources, while banks put up with losing a significant part of the affected loans to support the programme. The amount of rent was regulated by a government decree on a mandatory basis. The law also guaranteed the right of repurchase: Borrowers were entitled to repurchase their homes if their financial situation improved. The borrower was able to apply for an interest subsidy for housing loans to repurchase his or her home.

The programme was originally planned for three years, but was later extended: The National Asset Management Company purchased 25 thousand homes by the end of 2014. By the end of 2018, 36 thousand residential properties had actually been taken over by the asset manager, so approx. 150 thousand people were affected by this kind of state aid. Based on authorisation by the Government, the National Asset Management Company had accepted offers for the purchase of more than 42 thousand properties by 31 May 2018, and financial settlement with the borrowers was still partly in progress at the end of 2018.

7. The complete phase-out of foreign currency loans and settlement with banks

Despite a number of Government measures providing a great deal of help to borrowers, in 2014 it was already obvious that a comprehensive solution had to be found to settle the situation of foreign currency borrowers both definitively and reassuringly. The solution had to simultaneously provide an opportunity to the banking system to break out of an endless spiral. The increasing number of non-performing loans severely worsened the profitability of the banks and lowered their lending capacity. This was to the detriment of the real economy.

The solution had to be based on insight into an extremely complex legal framework, and the room for flexibility had to be clarified. Furthermore, legislative changes to a large number of civil law contracts raised questions regarding constitutionality, and the reliance of consumer credit regulations on EU legislation also had to be taken into consideration.

In addition to legal complications, some fundamental economic policy issues also came up. It was only possible to even consider the HUF conversion of foreign currency loans in a healthy banking system, with stable macroeconomic foundations, proper equilibrium indicators, and much lower HUF interest rates than at the time of taking out the loan. The inadequate timing of settlements and the phase-out of foreign currency loans could even have been harmful to borrowers.

Therefore, the decisions of the Constitutional Court of 28 February 2013 and 24 March 2014 represented a true milestone. Based on the interpretation of the Constitutional Court, the National Assembly could exceptionally change the content of civil law contracts if the borrowers’ homes were at risk or in the event of an abuse of a dominant position by credit institutions. Furthermore, on 30 April 2014 the European Court of Justice decided (because of the involvement of the relevant EU Directive) that Hungarian courts were also entitled to investigate the unfairness of foreign currency loan contracts. Subsequently, in its uniformity decision of 16 June 2014, the Curia declared that the legal answer to the question raised by many in thousands of lawsuits was that the exchange rate proliferation was unfair in all foreign currency loan contracts. The Curia also concluded that, in the absence of proof to the contrary, the unilateral contract amendments for residential loans by banks did not meet the requirements of fairness.

The decision of the Curia in June 2014 gave a legal opportunity to the National Assembly to provide a comprehensive solution to the problem. The decision of the Curia created a special situation: hundreds of thousands of borrowers felt encouraged to sue based on the uniformity decision, in the hope of sure success. However, such a large number of legal actions would have completely paralysed the Hungarian judicial system, and the plaintiffs would have had remedy only after many years. The Government therefore decided that the issue should be dealt with and resolved at a legislative level, and the act adopted in July 2014, based on the uniformity decision of the Curia, declared the nullity of the contractual clause on the application of the exchange rate proliferation and made a presumption regarding the unfairness of clauses on unilateral contract amendment.6

6 Act XXXVIII of 2014 on the resolution of questions relating to the uniformity decision of the Curia regarding consumer loan agreements of financial institutions.

During 2015, banks were required by law to settle accounts for the refund of overpayments due to the unfair exchange rate proliferation and unilateral contract amendments with those clients who had taken out a foreign currency loan with them. In the course of the settlement process, banks sent out 2.1 million letters and the refunded, credited amount came to nearly HUF 750 billion. This resulted in a significant reduction of burden for households.

The amount to be repaid fell considerably, and the amount of outstanding principal also decreased, resulting in a 25 per cent reduction in monthly payments.

The repayment obligation of clients was further reduced by the fact that, from 1 February 2015, fair interest rates had to be restored for all loan contracts affected by the settlement process, which typically meant the restoration of the interest rates applied when the contract had been signed.

8. HUF conversion of mortgage loans

The settlement process, the reduction in outstanding principal achieved through the act, and the lower payments would only have been useful for the population in the long term if the exchange rate risk still present in the new situation was eliminated. This was the purpose of the act on the HUF conversion of loans.7 The act, which entered into force on 1 February 2015, ensured the conversion of both mortgage loans for housing purposes and home equity loans. The banks converted the loans of nearly 500 thousand borrowers into HUF. It was important that the conversion should take place at market rates, in accordance with the decision of the Curia.

According to preliminary estimates, the amount of foreign currency that had to be converted into HUF was around EUR 9 billion. The question arose as to how to prevent the conversion of this large amount of money from causing serious disruption in the market, and how to keep the exchange rate stable. To avoid speculation, the exchange rates to be applied for conversion were fixed on 7 November 2014: HUF/CHF 256.47 (the average of the period elapsed since the Curia decision of 16 June 2014), HUF/EUR 309.97 and HUF/JPY 2.163 (official MNB exchange rate of 7 November 2014). Based on its agreement with commercial banks, the MNB provided the necessary foreign currency at the expense of its own reserves to ensure the conversion took place in a professional manner, without market disruption.

The HUF conversion protected the population from further significant burdens. The conversion was performed at the exchange rate fixed in November 2014, but the HUF/CHF exchange rate was already significantly higher at the beginning of 2015, because the Swiss National Bank unexpectedly abolished the CHF/EUR exchange rate cap (CHF/EUR 1.20) in the second half of January 2015.

The positive effects of the HUF conversion of mortgage loans were already visible in the short term: As a result of the exchange rate fixing at the end of December, immediately preceding the HUF conversion, the dramatic weakening of the HUF against the CHF in mid-January 2015 no longer exacerbated the payment burdens of mortgage borrowers and the risk exposure of banks.

Therefore, the significant national economic risks associated with residential loans were not realised.

7 Act LXXVII of 2014 on settling certain issues related to the conversion of the currency of certain consumer loan agreements and to the rules governing interest rates

Croatia and Poland were not in such a favourable position. In both countries, indebtedness in foreign currencies, mainly in Swiss francs, was also causing serious difficulties, but the resolution to the problems of foreign currency borrowers did not progress as far as in Hunga- ry. In Poland, payments for Swiss franc borrowers increased by more than 15 per cent, and in Croatia by nearly 10 per cent, compared to the amount payable a year before. Without the HUF conversion, the debts of citizens would have increased by approx. HUF 400 billion in Hungary too. This would have meant more than 10 per cent higher payments on average.

9. HUF conversion of other consumer loans

Residential foreign currency loans other than mortgage loans continued to be associated with an exchange rate risk. The appreciation of the Swiss franc in January 2015 raised the burden on borrowers with foreign currency-denominated consumer loans. Therefore, after the HUF conversion of foreign currency mortgage loans, the Government looked for a solution for the HUF conversion of remaining car and personal loans as well. Although the volume of such loans (HUF 305 billion) was significantly lower than that of mortgage loans, a large number of households were affected as the number of contracts exceeded 240 thousand.

On 22 September 2015, the National Assembly adopted an act regulating the HUF conversion of foreign currency-denominated car and consumer loans, which affected about 200 thousand contracts.8 The banks and the state both took over half of the burden caused by the difference between the exchange rate used for mortgage loans in November 2014 and the exchange rate in August 2015 (HUF 15 billion each).

This measure resulted in payments of about 10-11 per cent lower. However, borrowers no longer faced exchange rate fluctuations and unpredictable monthly repayments.

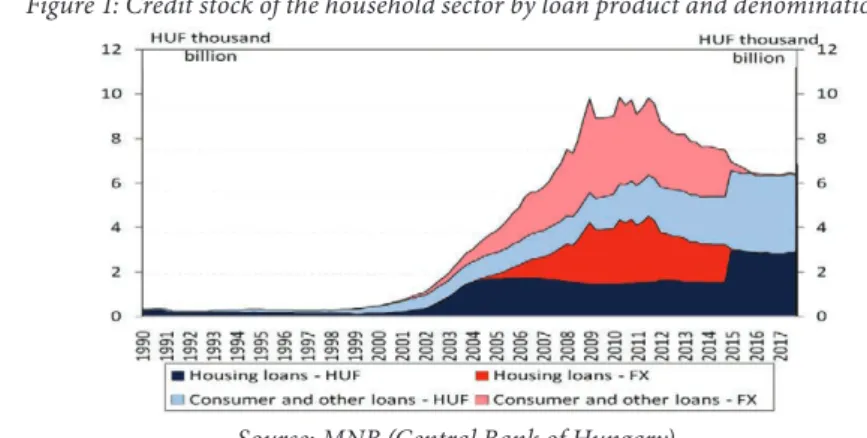

As a result of these Government measures, residential foreign currency loans were virtually phased out completely in Hungary by 2016. This is also reflected in the statistics, as the share of foreign currency loans within the total volume of residential loans reached 71 per cent by 2009, while it dropped to less than 1 per cent by the beginning of 2016.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Piotr J. SZPUNAR - Adam GLOGOWSKI: Lending in foreign currencies as a systemic risk Macroprudential Commentaries, ESRB, Issue: No:4, December 2012. ECB, Frankfurt

2. Ch. BEER - S. ONGENA - M. PETER: Borrowing in Foreign Currency: Austrian Households as Carry Traders, Österreichische Nationalbank, 2009, Vienna

3. BALOG Ádám-NAGY Márton: A bankok erőfölénye a devizahiteles problémában (MNB honlap)

4. BALOGH László: A banki hitelezés dinamikája Magyarországon. Előadás Világgazdaság-konferencia - 2010. december 2.

5. BALOGH László: A devizahitelezéssel összefüggő kérdések felügyeleti szemszögből. Előadás, Pécsi Pénzügyi Napok, 2011.

8 Act CXLV of 2015 on resolving issues concerning the HUF conversion of receivables arising from certain consumer loan contracts.

ANNEX

Background tables

Amount of housing loans granted in the reference period (in HUF million)

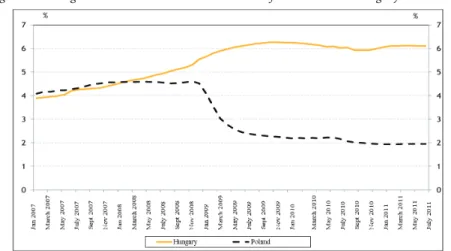

The development of the average interest rates on foreign currency mortgage loans for housing purposes for new and existing contracts in Poland, Hungary and Romania (source: MNB)

Interest rate of loans denominated in forints, euros and Swiss francs

Trends in interest rates

Average interest rates of bank loans and Interest of forint- and Swiss franc-based housing loans deposits denominated in forints compared to the target base rate of the Swiss Central Bank

Source: MNB, Central Bank of Hungary Source : MNB, Central Bank of Hungary

Vice-President

Hungarian Banking Association

IT’S ALL ABOUT TIMING – ON THE CONVERSION OF

FOREIGN CURRENCY BASED LOANS

The government and the Hungarian Banking Association signed the agreement on the conversion into forints of foreign currency based household mortgage loans on 9 November 2014. This was followed on 25 November 2014 by the adoption by Parliament of Act LXXVII of 2014 on the settlement of issues related to the conversion of the currency of certain consumer loan agreements and rules regarding interest (the so-called Settlement Act). Pursuant to the Settlement Act, the financial institutions were required to convert foreign currency-based loan agreements until 31 March 2015. When defining the monthly instalments however, as of 1 January 2015, they were required to apply the fixed exchange rate determined in legislation (EUR: 308.97 HUF, CHF: 256.47 HUF, JPY: 2.163 HUF).

This overview will evaluate regulatory measures necessary to ensure the conversion into forints of the foreign currency based loans by examining the timing and the method of conversion as well as comparing the Hungarian experience with that of other countries of the region.

1. The Timing of Conversion

When assessing legislative intervention targeting the conversion of foreign currency based loans, it is appropriate to identify the legal and economic conditions without which the measures could not have been successfully implemented. In doing so, one should also consider when these conditions emerged.

1. 1. Legal environment

• Civil Law Uniformity Decisions 6/2013 (‘6/2013 PJE’) and 2/2014 (‘2/2014 PJE’) of the Curia offered clear guidance on the treatment of the exchange rate margin and of the unilateral amendment of contracts. They served as a key reference for legislation that eventually paved the way to conversion.

• Parliament followed up Decision 2/2014 PJE by adopting Act XXXVIII of 2014 on settling certain issues relating to the uniformity decision of the Curia in respect of consumer loan contracts entered into with financial institutions and later Act XL of 2014 on the rules of settlement regulated in Act XXXVIII of 2014 on settling certain issues relating to the uniformity decision of the Curia in respect of the consumer loan contracts entered into by financial institutions, and certain other provisions.

• Additionally, Decision 6/2013 PJE of the Curia also held that the fact itself that the exchange rate changes burden the debtor in exchange for the more favourable interest rate does not render the foreign currency based loan contract arrangement unlawful, obviously immoral, usurious or sham, nor is the contract aimed at impossible services.

This was also confirmed by Decision 2/2014 PJE which stated that the clause of a foreign currency based loan contract which stipulates that the risk of foreign exchange rate shall be taken without restrictions by the consumer – in exchange for a favourable interest rate – forms part of the main subject matter of the contract, therefore, as a main rule, its unfairness is exempt from assessment. The decisions passed down by the Curia with regard to exchange rate risks had clarified that conversion was to take place at market rates prior to the adoption of the Settlement Act.

1. 2. Economic environment

• By the end of 2014 the National Bank of Hungary (‘MNB’) was able to provide sufficient foreign currency for the purposes of conversion into forints owing to a favourable constellation of the volume of foreign currency based mortgage loans (EUR 9 billion), the foreign reserves of the MNB (EUR 35-37 billion) and short term external debts (EUR 21 billion). Whereas in previous years the foreign currency reserves were at the same level (from 2010 EUR 35+/- 4 billion), the volume of foreign currency based loans was larger (peaking at EUR 19 billion) and the short-term external debt higher (between 2010-2012-ben EUR 35-38 billion).

• The initiative could only succeed if it could be ensured that conversion into forints would not entail the increase of instalments for the customers. Reasonably, the total cost in forints could not exceed the total cost in foreign currency before conversion. As a result of the interest rate reduction cycle, the 7% base rate applicable in the summer of 2012 dropped to 2.1% by the autumn of 2014, which was closely followed by the decrease of the 3-month BUBOR. Owing to the decline of BUBOR to 2.1%, the gap between the cost of borrowing funds in forints and Swiss francs diminished significantly, the banks did no longer need to face further considerable losses after write-offs associated with settlement made in accordance with Act XL of 2014.

With the hindsight of four years, we can state that the timing of the conversion as well as the legal and economic conditions were ideal as all the ingredients had come together by the end of 2014 to implement the measures with success. As for timing, it should be stressed that the conversion of loans into forints applied from 1 January 2015 protected the customers and the financial sector from the hardly foreseeable negative economic consequences of the 2015 exchange rate shock.

2. Conversion: Its Impact on Customers, the Banking Sector and the National Economy

Economic actors believe that the conversion of foreign currency based loans into forints represented one of the most impressive measures taken by the central bank and the government, moreover both the design and the implementation were correct. The benefits of conversion are enjoyed by customers owing to smaller burdens, by the banking sector owing to the mitigation of credit risk and to the strengthening of financial stability as well as by the national economy through its reduced vulnerability.1

1 On the impact of conversion see: KOVÁCS Levente: Pénzügyi szektor a bizalmatlanság árnyékában. In: KO- VÁCS Levente – SIPOS József (ed.): Ciklusváltó évek, párhuzamos életrajzok. Arcképek a magyar pénzügyi szektorból, 2014-2016. Magyar Bankszövetség, Budapest, 2017. 16.

2. 1. MNB’s foreign currency sale program prevented the further weakening of the forint

The MNB realized that the required amount of foreign currency (EUR ~9 billion) could not be obtained through market transactions as that could have evere repercussions on the forint’s exchange rate. According to a study published by the experts of the MNB2, a depreciation of 30% could have been projected based on data from 2008.

To avoid this, the central bank sold foreign currency from its reserves in the value of EUR 9 billion to banks by carrying out coordinated tenders in the fourth quarter of 2014 and in January 2015. Out of this amount, around EUR 8 billion was linked to conversion (the banks were trying to hedge the net position resulting from the difference between the receivables amounting to EUR 9 billion and an impairment loss of EUR 1 billion) and EUR 1 billion was due to capital reduction resulting from settlement. The banks were required to hedge against the EUR/CHF exchange rate risk, this however did not cause any problems owing to the far broader EUR/CHF market.

The MNB took into account that the various market actors achieved closed currency positions with different methods. While some of the banks held foreign currency deposits within the balance sheet, other financial institutions used off-balance sheet swap transactions to finance their foreign currency loans. Whereas the central bank provided the first group with a facility (in a value of HUF 601 billion) that was conditional upon reducing short- term debts, those entering a swap transaction were granted a longer-term unconditional instrument in the total value of 2,216 billion forints.

2. 2. The conversion performed at the end of 2014 protected debtors from the exchange rate shock of early 2015, and the decreasing BUBOR favoured customers

• On 15 January 2015 the Swiss Central Bank abandoned the 1.2 EUR/CHF exchange rate cap, which resulted in the considerable appreciation of the Swiss franc. As opposed to the exchange rate of 256.47 CHF/HUF applied at the time of the conversion, the exchange rate exceeded even 320 CHF/HUF on 18 January 2015. Although the Swiss franc has weakened somewhat since then, the CHF/HUF exchange rate has not once moved below the 256.47 rate used for conversion. The ~285 CHF/HUF exchange rate valid at the time of writing the present review is still 11% higher than the fixed conversion exchange rate.

• In early 2015 the instalment of the average CHF mortgage loan transaction of 6.5 million forints was HUF 62,000 following settlement and conversion. Had conversion not been implemented, an average customer would have been confronted with a nearly 20% higher instalment amounting to HUF 73,000 due to the strengthening of the Swiss franc. Whereas the 3-month BUBOR stood at 2.1% at the time of the conversion, it ranged between 2-30 basis points in 2018. As a result, the HUF 62,000 instalment of the average customer was reduced to HUF 56,000 (-10%). Without conversion, the

2 KOLOZSI Pál Péter - BANAI Ádám - VONNÁK Balázs: A lakossági deviza-jelzáloghitelek kivezetése: időzítés és keretrendszer. Hitelintézeti Szemle, 2015. 3. sz. 60-87.