Katalin N. Kollár Gabriella Pajor

Vera Piros Mónika Somogyi

Éva Jármi Emese Vágó

Ferenc ze

Copyright © 2014 Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, Pedagógiai és Pszichológiai Kar, Pszichológiai Intézet, Iskolapszichológia Tanszék

Chapters by authors

1. Katalin N. Kollár: School psychology – theoretical issues and practical consequences

2. Gabriella Pajor: Results and implications of current researches in the field of social psychology at school 3. Gabriella Pajor: Current issues and problem areas of educational psychology

4. Vera Piros: Development of psychical functions in learning

5. Mónika Somogyi: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Forth UK and Hungarian Edition - WISC-IV Demonstration 6. Vera Piros – Emese Vágó: Methodology of learning

7. Éva Jármi: Learning disabilities

8. Katalin N. Kollár: Consultation – case studies 9. Emese Vágó: Studying school organizations

TÁMOP 4.1.2.A/1-11/1-2011-0018

Table of Contents

1. School psychology ... 1

1.1. First steps to the emergence of school psychology ... 1

1.2. Environmental factors in the progress of school psychology ... 1

1.3. What does school psychology mean? ... 2

1.4. Conceptual issues in school psychology ... 4

1.5. Whom school psychologists have to work with? ... 5

What is the division of labour among the different professions? ... 5

Level of prevention ... 5

Level of intervention ... 6

Is the focus of school psychology on special groups or on all school children? ... 7

Working with individual persons or with groups? ... 8

Organisation of services in school psychology – independent or in-school service? ... 8

Who is the client of school psychologists? ... 9

1.6. School psychology in Hungary ... 9

First steps in school psychology ... 9

Number of school psychologists ... 10

Concept and regulation in 2014 ... 13

1.7. References ... 14

2. Results and implications of current researches in the field of social psychology at school ... 15

2.1. The role of the social context in personality development ... 15

2.2. Social support and achievement ... 16

2.3. Bullying as a social phenomenon: the role of peer support ... 18

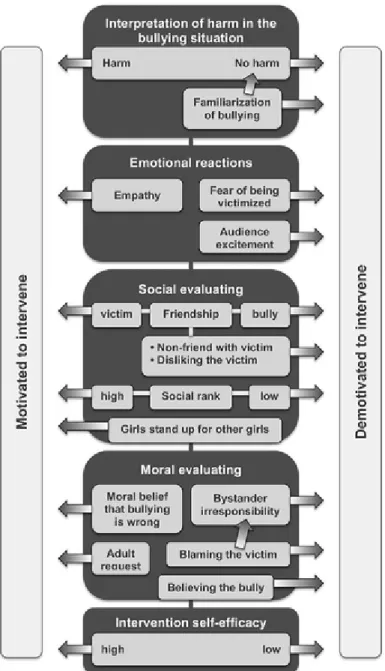

2.4. Bystanders' role in the act of bullying ... 20

2.5. Interpretation of harm in the bullying situation ... 23

2.6. Emotional reactions ... 24

2.7. Social evaluating ... 24

2.8. Moral evaluating ... 25

2.9. Intervention Self-Efficacy ... 25

2.10. Summary ... 26

3. Current issues and problem areas of educational psychology ... 27

3.1. Introduction ... 27

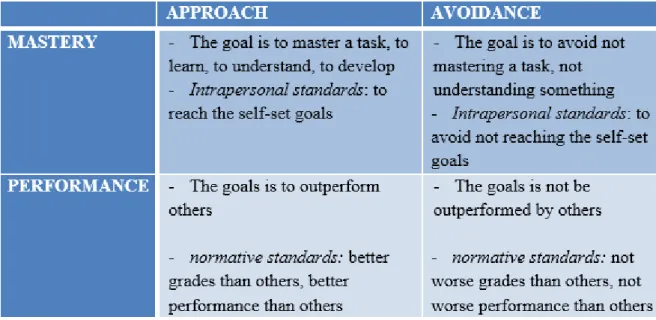

3.2. Theories of achievement motivation that dominate current researches in the field of educational psychology ... 27

Self-Determination Theory ... 27

Achievement Goal Theory ... 31

3.3. Activity ... 37

4. Development of psychical functions in learning ... 39

4.1. Methods of prevention ... 39

4.2. Assessment of learning disabilities ... 39

4.3. Games which develop physical functions ... 44

4.4. Secondary problems of students with LD. ... 44

4.5. Methods and possibilities of intervention ... 45

5. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Forth UK and Hungarian Edition ... 49

6. Methodology of learning ... 50

6.1. Students' attitudes to learning ... 50

6.2. Development of basic psychical functions in learning ... 51

6.3. Games to develop cognitive functions ... 54

Warm-ups, ice-breakers ... 54

Developing attention and memory ... 55

6.4. Complex techniques and strategies of learning ... 56

6.5. An example of effective learning technique - Mind map ... 57

6.6. Learning styles ... 59

7. Learning disabilities ... 60

7.1. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ... 60

DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD ... 60

Evaluation process ... 61

Overdiagnosis ... 61

Epidemiology ... 61

Etiology ... 62

Acquired brain lesions and ADHD ... 62

Neuroanatomy ... 62

Conceptualizations of ADHD ... 63

Primary (?) cognitive deficits in ADHD ... 63

EF-tests ... 63

Two prefrontal networks ... 66

Sonuga-Barke: dual-pathway model ... 68

Therapy ... 69

Medication ... 69

Behavioral therapy ... 69

Frequently used objectives for ADHD children ... 69

7.2. Developmental Dysphasia ... 69

Speech (vs. language) impairment ... 69

Specific Language Impairment (SLI) or Developmental Dysphasia ... 70

Symptoms ... 70

Late talkers vs. SLI ... 71

Developmental delay or disorder ... 72

Debate over nonverbal ability ... 72

Epidemiology and Etiology ... 72

Educational impact of SLI ... 73

Assessment ... 73

Intervention ... 74

7.3. Developmental Dysgraphia ... 75

Definition ... 75

Interdependence of transcription and generation ... 75

Symptoms ... 76

Subtypes ... 77

Handwriting ... 77

Spelling ... 78

Composition ... 78

DG independent disorder? ... 78

Epidemiology and Etiology ... 78

Assessment ... 79

Treatment of handwriting difficulties ... 79

Treatment of spelling difficulties ... 81

Developing composition skills ... 82

Accomodations ... 82

More tips... ... 82

7.4. Developmental Dyslexia ... 83

Definition ... 83

Pseudodyslexia ... 84

Spelling deficit in DL ... 84

Epidemiology ... 85

Ethiology ... 85

Warning signs (4-8 years) ... 86

Warning signs (Grades 3-8) ... 87

Common reading errors ... 88

Fundamental Skills Necessary for Proficient Phonologic Processing ... 89

Subtypes of DL ... 89

Core cognitive processes ... 90

Other DL-theories ... 92

Assessment ... 92

Intervention ... 93

Prevention ... 94

7.5. Developmental Dyscalculia ... 94

Dyscalculia is not trouble with math ... 94

Epidemiology ... 95

Definition of DC ... 95

Concept of numerosity ... 95

Biologically primary quantitative abilities (GEARY) ... 96

Biologically secondary number, counting, and arithmetic competencies ... 97

Conceptualistions of DC ... 98

Mental number line ... 98

Four-step developmental model of numerical cognition (Von ASTER and SHALEV) ... 99

Subtypes of DC ... 100

MiniMath test ... 100

Principles of MiniMath test ... 100

Measuring basic number skills ... 100

Interventions ... 101

Classroom Instruction ... 101

Tutorial Interventions ... 102

The Number Race ... 102

8. Consultation – case studies ... 103

8.1. Description of the problems – case studies ... 103

Case 1. András ... 103

Case 2. Zsuzsa ... 104

Case 3. Eszter ... 104

Case 4. Gábor ... 105

Case 5. The "broken" class ... 106

8.2. Questions for analysing case-studies ... 106

9. Studying school organizations ... 109

1. School psychology

Theoretical issues and practical consequences

1.1. First steps to the emergence of school psychology

School psychology is a relatively young field of psychology. However, the first representative was Cyrile Burt working as school psychologist from 1905 in the USA, so we can say with pride that this field has a hundred years history. It is useful to study the events of the international history of this field because there are many similarities or parallel phenomena in it.

In the development of school psychology roughly three main periods can be identified. The first step was the assessment of cognitive abilities. This was the main field of activity in the first half of the 20th century. In the next period emphasis was on individual treatment of pupils, in many cases this meant psychotherapy. Recently school psychology is defined as a more complex job with a larger scope of activities. Psychologists work not only with pupils but with teachers, other school workers and parents too. The field of their interest is not only a learning problem or individual emotional, motivational or behaviour problems but social problems, class management and mental health as well.

1.2. Environmental factors in the progress of school psychology

There are several external events inspiring the development of school psychology. It happened several times that a demand of the school system or of the society on the whole on the one hand, and a new chance of the profession on the other hand met. Let us see these examples!

The first step in the development of school psychology was the assessment of intelligence. The construction of the Simon-Binet intelligence test for children allowed the selection of the below average intellectual achievement. At the beginning of the 20th century the attendance of school became compulsory and the demand for the achievement prediction heightened.

One other example of the need for school psychology dates back to France in the 20s and 30s of the last century for two reasons (Marc 1977)1. The first reason for the establishment of the vocational guidance service was that many young people were soldiers in the first word war, and returning to the civil life they needed help to find a profession. At the beginning the advisors were only experts of the labour market, but in the first National Vocational Guidance Centre counsellors were psychologists too, among them very famous personalities like Piéron and Wallon. The other event that facilitated the development was the economic crisis in 1929-1933.

As a further inspiration the Langevin-Wallon plan in France in 1947 can be mentioned. This educational reform was designed by the developmental psychologist Henri Wallon. In this document of educational reform the necessity of school psychologists in all schools was declared. The first step of the development in school psychological service in France was mainly due to this educational reform.

1Marc, P. (1977): Les Psychologes dans l'Institution Scolaire, Coll."Paidaqides", Le Centurion, Paris

Our fourth example is the grand expansion of child psychotherapy on the field of school psychology after the 2th world war in the USA (Bardon, Bennet 1974)2. This was fostered by the Mental Health Movement and the rising of emotional and behavioural difficulties among schoolchildren.

1.3. What does school psychology mean?

How can we define school psychology, and why is it necessary to define the topics of this field? Studying the history of school psychology we can consider that the definition of this field has changed from time to time and there are different concepts behind these definitions.

Common feature of the definition is to deal with educational questions, but the detailed scope of duties have changed from time to time and differentiate in different states. In our time there are common trends, however, there is no solid definition for the required tasks in this field.

Guillemard (1982)3 at the beginning of the 1980s described three main directions in the French school psychology: psycho-educational, clinical and socioeconomic direction.

1. The psycho-educational direction

The main idea of this direction is accepted by almost all school psychologists. Their main task is to help schoolchildren adaptation to school, but this adaptation has to be mutual, school has to change too. To help children psychologists assess abilities and discover the reasons of learning difficulties. Their contribution to designing individual development plans and consultation with teachers on educational questions is as important as the efficacy of teacher training.

2. Clinical direction

School psychologists working based on this conception focus on the individual problems of pupils. They are open to personality problems and treat their clients with individual methods like drawing therapy or play therapy. They use only a few tests prefer projective tests as T.A.T. or Rorschach. They are more interested in personality problems and less in learning difficulties or other problems concerning school. They are sometimes called psychotherapist and some of them also agree with this title, however school is not suitable for realizing psychotherapeutic attitude. The need for individual counselling or therapy is extended not only in France but all over the world, but in France a network of child guidance clinics was lacking. So we can understand their orientation toward individual problems of pupils.

3. Psychosocial direction

In the beginning this direction was relatively new, but Guillemard predicted it to spread, and he was right.

In this approach attention extend from individual problems to the whole psychosocial environment. There were two main streams within this direction. The first one was mainly a sociological approach, inspired by the investigations of Bourdieu and Passeron. The main problem in the focus was failure at school. The main reason for this problem proved to be economic and social disadvantage. Representatives of this stream believe that school reform is the adequate solution to this problem.

2Bardon, J.I., Benett V. C. (1974): School psychology. Prentice Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

3Guillemard, J. C. (1982): Les psychologues á l'école. Collection Information Permanente, Press Universitaires de France, Paris.

The other stream focuses on the interaction between individuals and their environment. The starting point of this ecological conception can be traced back to Kurt Lewins' environmental concept. Analysis of micro- and macro environments of a schoolchild helps psychologists to understand his problem and find solutions.

Their attention reaches the social network of a child like family members and other important persons, and the communicational network too.

In the United States Ysseldyke, Reynolds and Weinberg (1984)4 identified 16 domains of school psychology:

"classroom management, classroom organisation and social structure, interpersonal communication and consultation, basic academic skills, basic life skills, affective/social skills, parent involvement, systems development and planning, personal development, individual differences in development and learning, school- community relations, instruction, legal, ethical, and professional issues, assessment, multicultural concerns, and research and evaluation." (Saigh, Oakland 1989 p. 233.)5

The definition of school psychology is in these days is still an open question. Merrell, Ervin, and Peacock (2012)6 in their book School Psychology for the 21st Century cite two definitions.

American National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) describes school psychology focusing on the outcomes or working areas, partnership and requirements of qualification:

"School psychologists help children and youth succeed academically, socially, behaviourally, and emotionally.

They collaborate with educators, parents, and other professionals to create safe, healthy, and supportive learning environments that strengthen connection between home, school, and community for all students.

School psychologists are highly trained in both psychology and education, competing a minimum of a specialist-level degree program (at least 60 graduate semester hours that includes a year-long supervised internship. This training emphasizes preparation in mental health and educational interventions, child development, learning, behaviour, motivation, curriculum and instruction, assessment, consultation, collaboration, school law, and systems. School psychologist must be certificated and/or licenced by the state in which they work. They also may be nationally certificated by the National School Psychology Certification Board (NSCB). The National Association of School Psychologists sets ethical and training standards for practice and service delivery. (NASP, 2010d, paragraphs 1 and 2.)" (Merrell, Ervin, Peacock 2012, p. 2.) From this definition we can assess two characteristics of the modern approach. On one hand, working areas of school psychology are wide. On the other hand, there are general standards of requirements but there are differences between the requirements among different states in the USA too. In the latest years average level of qualification has become higher, percent of school psychologists having PhD. degree extended, 75% are nondoctoral persons (www.apa.org).

To some extent different definition is given by the Division of School Psychology of American Psychological Association (APA). It focuses more on concrete tasks of school psychologists:

4Ysseldyke, J. E., Reynolds, M. C, Weinberg R. A. (1984): School psychology: A blueprint for training and practice. Minneapolis: National School Psychology Inservice Training Network.

5Oakland, Th. D. (1989): School Psychology in the United States of America. In: Saigh, P. A., Oakland, Th.: International Perspectives on Psychology in the Schools. LEA Hillsdale, New York 223-237. pp.

6Merrell, K. W., Ervin, R. A., Peacock, G. G. (2012): School Psychology for the 21st Century. Foundations and Practice. The Guilford Press New York, London

"School Psychology is a general practice and health service provider specialty of professional psychology that is concerned with the science and practice of psychology with children, youth, families; learners of all ages; and the schooling process. The basic education and training of school psychologists prepares them to provide a range of psychological diagnosis, assessment, intervention, prevention, health promotion, and program development and evaluation services with a special focus on the developmental processes of children and youth within the context of schools, families and other systems.

School psychologists are prepared to intervene at the individual and system level, and develop, implement, ad evaluate preventive programs. In these efforts, they conduct ecologically valid assessments and intervene to promote positive learning environments within which children and youth from diverse backgrounds to ensure that all have equal access to effective educational and psychological services that promote healthy development."

(www. apa.org /ed/graduate/specialize/school.aspx, cited by Merrell, Ervin, Peacock 2012, p. 2-3.)

In this definition we can observe the main characteristics of modern approach in school psychology. This leads us to the conceptual issues of school psychology.

1.4. Conceptual issues in school psychology

Direct or indirect intervention

One of the basic questions of school psychological service is the strategy of problem solving. Traditionally school psychology was defined as a direct service. School psychologists assessed pupils’ characteristics – cognitive achievement, individual traits to identify their problems and find proper methods of intervention or counselling. From different reasons this approach alone was not satisfying. Direct and indirect service delivery together foster children’s wellbeing and an effective educational environment.

Direct service

• early identification

• assessment

• psychoeducational program planning

• intervention

• follow-up Indirect service

• prevention

• consultation

• training, education, supervision

• administration

• research

(Reynolds, Gutkin, Elliott, Witt 1984 after Standards for Credentialing in School Psychology)7

7Reynolds, C. R., Gutkin, T. B.; Elliott, S. N.; Witt, J. C. (1984): School Psychology: Essentials of Theory and Practice. New York, Wiley.

Hilldale, New Jersey. LEA.

1.5. Whom school psychologists have to work with?

In direct service delivery school psychologists work with schoolchildren individually, with small groups of them or with classes. In this case there are also differences in age level of pupils. In many cases school psychologists work with preschool children too, because early identification and early development of cognitive abilities, linguistic competences or a correction of behaviour problems have particular importance.

An example for this early intervention is France where 92 percent of children and almost all children at age 4 or above attend pre-elementary school (Guillemard 1989)8. Early assessment and early identification help to develop special educational programs for these children and school psychologists often contribute in this program planning.

In contrast, in the United Sates minority of school psychologists work with preschool children, only5 % in 1989 (Oakland 1989).

In many cases there is no balanced psychological service, service is not equally available for all age groups. It depends not only on the conception influencing the service delivery but also on available other specialists.

What is the division of labour among the different professions?

This is much more a practical question, however, it has bearing with theoretical questions too. We can find expressive examples for the influence of the presence or shortage of related fields.

In France from the third decade of the 20th century vocation guidance service was available, and the development of this service was dynamic. There was progress in school psychology too, but there was a division of working places. School psychologists worked in kindergarten and elementary schools and vocational counsellors worked in high schools. From the formerly mentioned Langevin-Wallon plan the progress in school psychology and school psychological service became dynamic, but the division of work remained (Guillemard 1982).

Another related field is school counselling. In many country one of the main tasks of school psychologists is counselling, but in USA school psychologists and counsellors work at the same schools. Average ratio of school counsellors to students in about 1:500, and the school psychologist/student ratio about 1:1500 (Fagan, Wise 20079, Merrell, Ervin, Peacock 2012).

Level of prevention

Caplan (1970)10 designed the frequently cited model of three levels of prevention.

Primary prevention aims at all schoolchildren, school psychologists' goal is to protect help pupils' healthy and harmonic development.

Secondary prevention deals with students with problems, learning difficulties, behaviour problems etc. Early identification and developmental courses are usual methods at this level.

8Guillemard, J. C. (1989) School Psychology in France. In: Saigh, P. A., Oakland, Th.: International Perspectives on Psychology in the Schools. LEA Hillsdale, New York 35-50. pp.

9Fagan T. K., Wise, P. S. (2007): School psychology: Past, present and future (3rd ed.). Bethesda, MA: National Association of School Psychologists.

10Caplan, G. (1970): The Theory and practice of mental health consultation. New York: Basic Books.

Tertiary preventions’ goal is to reduce secondary symptoms of problem children. Teachers and parents require help when problems occur. Generally there is pressure on school psychologists to deal with actual problems but primary prevention could be prospectively more effective. This model is useful in school psychology but for the use of methods of primary prevention school psychologist have to focus on supportive activity. Primary prevention deals not only with students but with school staff too.

Level of intervention

Traditionally school psychologists work with individual students. The reciprocal determinism model described by Bandura (Reynolds, Gutkin, Elliott, Witt 1984) emphasizes the importance of environmental factors.

According to this model it is useful to work with other significant persons as parents, teachers or friends of the client. But in some cases problem solving is effective only on system level. If we consider repeated problems, as bullying or frequent failure at school, it is necessary to make changes on the system level: group organization, teaching methods etc.

Ester Cole and Jane A. Siegel edited the book Effective Consultation in School Psychology (Cole, Siegel 2003)11. Figure 1 is constructed based on their model for psychological service in school. They categorised the case studies presented in their volume with the help of three categories: the level of prevention, clients of the service and direct or indirect service.

11Cole, E., Siegel, J. A. (eds. 2003): Effective Consultation in School Psychology. 2. eds. Hogrefe and Huber, Göttingen

Figure 1.

Is the focus of school psychology on special groups or on all school children?

This question is strongly connected to the previous question, the choice between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. In the last thirty years integration of handicapped students in schools in Western countries is a general tendency and a consciously undertaken goal of the educational systems. This is a challenge for teachers, who are in many cases little prepared for this task. For this reason school psychologists have to deal with problems of integration, but the setting of concrete tasks determine methods as consultation with teachers of handicapped children, or improving their social integration by organizing psychological activities for the whole class can be effective. In some cases direct support to the integrated pupils is also necessary, but the ratio of direct and indirect events is determinant.

Similar problem is the focus of school psychologists’ activity between below average, average and above average pupils. Gifted children get frequently less attention, however, above average abilities can be the final reason of behaviour problems, low motivation or other difficulties if teaching methods are not enough differential.

Working with individual persons or with groups?

Many individual problems of schoolchildren are effectively treated by counselling. For example many students in the last school year need help in vocational choice. Students with similar problems could be helped not only individually, but vocational guidance can be realised in group too, and there are other advantages of these groups out of time saving for psychologist. Group members in similar situation can offer support to each other, and a training in group has possibilities for developing interpersonal skills too.

Organisation of services in school psychology – independent or in-school service?

School psychologists work at school, however, there are two main types of organisations. In some cases school psychologists belong to the school, their principal is the school director, and in other cases school psychologists belong to an independent organisation, a child guidance clinic or an independent school psychological board.

Belonging to one school means that the school psychologist is part of the school staff. The school psychologist is easily available for teachers and pupils, and he/she is integrated in the everyday life of the school. The main difficulty of this model is isolation. Many school psychologists miss contact with other colleagues and need a supervisor.

In France school psychologists work at school, alone as psychologist but in a team called G.A.P.P. (Groupe d'Aide Pscho-Pedagogique) Psycho-pedagogic Aid Group. In these groups three experts work together, one school psychologist, one specialist of psychoeducation and one expert of psychomotor development.

In other cases school psychologists are located in service centres, like a child guidance clinic or a pedagogic board. They work regularly with the same schools, for example in the USA typically with two or three schools, but their relationship with schools is less close than in the one psychologist-one school model. Psychologists profit from this organisational model: the advantages of team work with colleagues and the professional independence. This independence is particularly important in the conflicts discussed in the next section.

Organisation of psychological services is connected to the psychologist/student ratio. In all over the world need for school psychological service is higher than the realised service. However the strategy of the establishment of the service is important. Having a shortage in school psychological service means not only that psychologists can finish fewer tasks in one school but some tasks cannot be realised at all. For example for effective consultation with teachers the trustful relationship among partners is required. If the school psychologist spends only short time pro week in a school and teachers have no chance to make acquaintance with him/her, they will rarely ask for a consultation.

On the other hand in any case (learning or behaviour problems, etc.) the first step is assessment. If there is not enough time, there could be "well-diagnosed" but unattended students, because for the next step we need time not only in the case of direct intervention but in any cases.

There is a minimum of psychologist/student rata that can work effectively, therefore if there is not enough source for a service in all schools (and this is the fact in many countries) it is more effective to establish service in the more problematic schools or problem areas (economic or ethnic problems) and establish the whole system step-by-step.

Who is the client of school psychologists?

Our last dilemma can be discussed from two aspects (Reynolds, Gutkin, Elliott, Witt 1984). One aspect is the extent of clients. According to the conception of reciprocal determinism model or a psychoecological approach clients of school psychologists are not only students in all age groups from age 2 or 3 until the end of schooling but other persons involved in the educational system – teachers, parents, other members of the school staff.

At system level school psychologists have to collaborate with agencies out of school and work with the whole school in system level too.

The proportion of the time spent for different tasks and different clients depend on different local factors too (Reynolds, Gutkin, Elliott, Witt 1984).

1. Concept of the psychologist or of the service where he/she works about school psychology 2. Competences provided by the training of psychologist

3. The school psychologist's idea of preventive mental health 4. Legal mandates (law, licence)

5. Financial questions (what are priorities in this workplace, in some cases the psychologist is financed by tenders for special tasks)

The other aspect of this question is much more challenging. There are real dilemmas when there is conflict of interest of different clients at school. The individual child's need differentiate frequently from classmates, he/

she needs special attention, extra patience from the teacher, but it requires adaptation from other classmates. In some cases the school as a whole has other interest than the individual child. Not only in the case of a problem child causing problems for the whole school, but in the case of a gifted child too. Talented children bring glory for their teachers or for the whole school, too. If the development of this student would be better in some other special school, their interests are in conflict too. School psychologists have to deal with these dilemmas, too.

1.6. School psychology in Hungary

First steps in school psychology

After some sporadic use of school psychologists in the 1970s and 1980s years the first step to the establishment of school psychological service was a pilot program lad by the Educational and Social Psychological Department of Eötvös Loránd University. The main question tested in this one year program was the usefulness of different methods of school psychology in Hungarian schools. The conception built on these experiences had four characteristics (P.Balogh, Szitó 1987)12.

It was a one school-one school psychologist model. Psychologists belonged to a certain school, directed by headmasters. Schools size was typically about 500 Student/school. School psychologists were helped from the beginning by a national organisation (Országos Iskolapszichológiai Módszertani Bázis / National Methodological Basis for School Psychology) operating at the Eötvös Loránd University, and for five years by another Basis, The Methodological Basis for School Psychology of South Lowland at the University of Szeged.

12P. Balogh Katalin, Szitó Imre (1987): Az iskolapszichológia néhány alapkérdése. Iskolapszichológia 1. ELTE Iskolapszichológiai Módszertani Bázis

The conception for school psychology was the preference of primary prevention. For this they used early identification and educative programs for mental health (preventive program on drug and alcohol, training for the improvement of group cohesion and development of competences of communication, etc.).

Among indirect methods first of all consultation was used instead of direct counselling with pupils with learning or behaviour problems. In direct service group methods were preferred. The overall conception was effectiveness for the improvement of academic performance and mental health of as many pupils as possible.

Psychotherapy was not task of school psychologists. In Hungary a network was established where psychotherapists worked. This network has not been equally available, in big cities there are child guidance services where children with emotional or mental problems would be sent, but in smaller towns child guidance services are missing, too.

Regulation of school psychological services did not exist until 2011. There was only a declaration of the Ministry of Education in 1989 (Hunyady, Templom eds. 1989)13 as an official document on school psychology.

It described the definition of this field of psychology and the principles mentioned before.

In the last 28 years there has been a slow but significant development in this field inspired by different influential factors. First, work places have been financed by the ministry of education. There was no law describing nor regulating school psychology before, however, the National Law of Education have permitted the employment of school psychologists in schools and afterwards in child guidance services, too.

From the 90s of the last century there has been a specialization in school psychology at MA level, and nowadays the MA specialisation is on counselling and school psychology. From the beginning of the employment of school psychologists there has been a two year long post gradual course, it is required for specialists working independently in schools.

Number of school psychologists

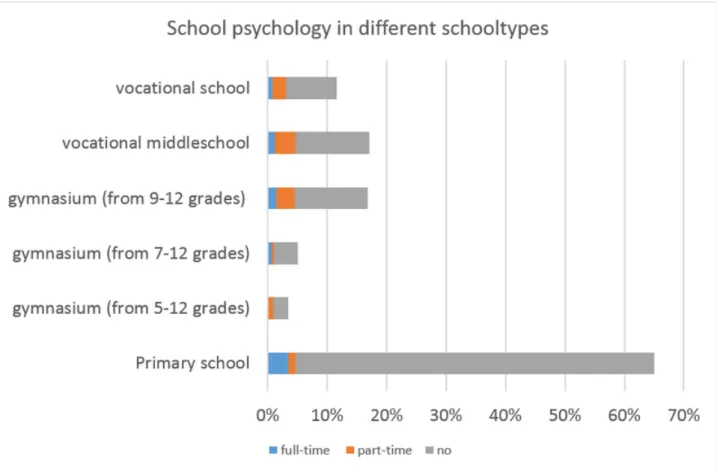

School psychologists work in schools and in kindergartens too. Majority of schools have no school psychologist at all, but the profession is well known among teachers. In Figure 2 the proportion of schools having school psychological service in year 2012 is presented.

Figure 2. Schools having school psychological service in Hungary in year 2012

School psychologist work only in 20% of schools, but in many cases there is shortage in schools having part- time service, because in the last years in many schools a school psychological service has been opened but it means only a few hours per week. Psychologists work full time only in 4% of schools. We have discussed the problem of part time service earlier.

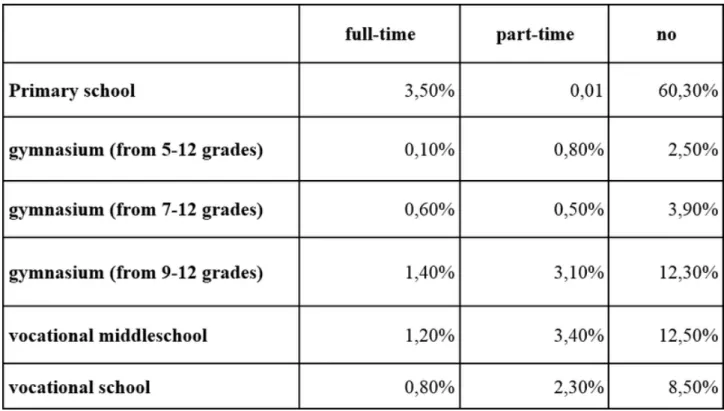

In Figure 3 we can consider the difference between different types of schools. It is natural that there are differences but the problem presented on Figure 3 is the direction of this difference. On one hand, the positive tendency is that vocational schools and vocational middle schools have more psychologists. Among gymnasiums the relatively better provided schools are the stronger ones. In Hungary school system is selective, and we can consider that in primary schools the shortage in school psychological service is higher.

Figure 3. School psychological services in different types of school The best provided schools are middle schools.

Among gymnasiums the types 5. to 12. and gymnasiums from 7. to 12. grades are in better situation because in these types the proportion of schools having school psychological service is higher (Figure 4)

Figure 4. School psychological services in different types of school There are differences between the different regions of Hungary, (Figure 5).

Figure 5. School psychological services in different regions of Hungary

The situation is better in three university centres, in Budapest, South-Transdanubium and North-Lowland, and school psychological services are missing in the regions where there is no possibility to graduate in psychology.

Concept and regulation in 2014

In the last two years regulation of the school system and of the psychological and special pedagogical services has changed. Regulation has become unified. Public schools and special services belong to the same centralised organisation (Klebersberg Center) and all educational districts will have a special service.

This reform is very large and we are only at the beginning. One of the most important goals is to balance the differences among district areas of Hungary.

According to this regulation school psychologists belong to schools, but until schools will have school psychologists – schools with more than 1000 students a fulltime specialist, schools between 500-1000 pupils a half time psychologist, and smaller schools a psychologist/1000 students, same schools in the neighbourhood - psychologists working in the special services can work in schools as school psychologists.

Conception of the tasks and the working methods have not much changed, only some additional tasks have become required.

One of the most significant developments is the declaration of compulsory employment in large schools. The National Law of Education prescribe the employment of a half-time psychologist for 500 pupils. The realisation of this ratio of 1 psychologist/ 1000 pupils has for instance financial limits, employment is prescribed only in schools larger than 500 pupils, but this is certainly the first step to a country-wide network.

The tasks declared in the afore mentioned law are personality development of pupils, mental health promotion and support of educational work.

Laws referring to school psychologists are available here in original version [http://pszichologia.elte.hu/

eltetamop412A1/scpsy/I_regulations_nurseryandschoolpsychology.pdf]

In details:

1. support for teachers

2. direct service to pupils individually or in groups for integration and healthy social relationship, for successful learning at school, and reducing psychical or mental problems (for example anxiety in connection with school achievement)

3. early identification and assessment (abilities, social relations, motivation, behavioural difficulties, learning problems) – first of all in first grade, then in grades 1. 5. 9. and early identification at age 5.

4. mental hygiene and primary prevention in health promotion, mental health support, conflict management, antibullying intervention

5. counselling in crisis and delegation to psychotherapy 6. taking care of gifted children

7. vocational guidance

8. education and spreading psychological culture

Clients of school psychologists are children alone or in group, teachers and parents.

Cooperation with other specialists and with colleagues in special services is required.

For professional support a coordinator – a team leader – works in special services, who is a professional leader of school psychologists working in their district.

It would be early to weigh the benefits or difficulties of this reform, but we hope that after twenty-eight years school psychology is getting closer to arriving one day in every school.

1.7. References

Bardon, J.I., Benett V. C. (1974): School psychology. Prentice Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Caplan, G. (1970): The Theory and practice of mental health consultation. New York: Basic Books.

Cole, E., Siegel, J. A. (eds. 2003): Effective Consultation in School Psychology. 2. eds. Hogrefe and Huber, Göttingen.

Fagan T. K., Wise, P. S. (2007): School psychology: Past, present and future (3rd ed.). Bethesda, MA: National Association of School Psychologists.

Gutkin,T.B.; Curtis,M.J. (1982): The handbook of school psychology. New York, Wiley.

Guillemard, J. C. (1982): Les psychologues á l'école. Collection Information Permanente, Press Universitaires de France, Paris.

Guillemard, J. C. (1989) School Psychology in France. In: Saigh, P. A., Oakland, Th.: International Perspectives on Psychology in the Schools. LEA Hillsdale, New York 35-50. pp.

Hunyady György; Templom Jánosné (szerk. 1989): Pszichológus az iskolában = Iskolapszichológus.

Továbbképzési füzetek 3. ELTE.

Marc, P. (1977): Les Psychologes dans l’Institution Scolaire, Coll."Paidaqides", Le Centurion, Paris

Merrell, K. W., Ervin, R. A., Peacock, G. G. (2012): School Psychology for the 21st Century. Foundations and Practice. The Guilford Press New York, London

Oakland, Th. D. (1989): School Psychology in the United States of America. In: Saigh, P. A., Oakland, Th.:

International Perspectives on Psychology in the Schools. LEA Hillsdale, New York 223-237. pp.

P. Balogh Katalin, Szitó Imre (1987): Az iskolapszichológia néhány alapkérdése. Iskolapszichológia 1. ELTE Iskolapszichológiai Módszertani Bázis

Reynolds, C. R., Gutkin, T. B.; Elliott, S. N.; Witt, J. C. (1984): School Psychology: Essentials of Theory and Practice. New York, Wiley. Hilldale, New Jersey. LEA.

Ysseldyke, J. E., Reynolds, M. C, Weinberg R. A. (1984): School psychology: A blueprint for training and practice. Minneapolis: National School Psychology Inservice Training Network.

www.ispaweb.org

2. Results and implications of current researches in the field of social psychology at school

During the development of an individual, environment and personality interact with each other, and the result of this interaction is a unique system of motives, goals, emotions, behaviours, etc. These can change with time and place, as the context changes too. The most important factors of the environment are definitely the others with whom the individual interacts directly: first the members of the family, then teachers, peers, and colleagues. In this chapter first we take a look at school as a social context in general, then we take a closer look at the classroom and the importance of belonging in that particular context, and finally we turn to the problem of bullying.

2.1. The role of the social context in personality development

People grow up in various social settings that shape their behaviour, emotions, thinking through the ways they interpret and perceive these different contexts. By adolescence children have had many favourable and unfavourable experiences in terms of the support family members, teachers and peers have provided, influencing their emotional, social, cognitive development. Social support "summarizes information that one is cared for, esteemed and valued, and part of a network of communications and mutual obligations" (Vedder et al, 2005)1. Social support contributes to well-being, what is more, perceived availability of it is a better predictor of well-being than actual support given. In school context social support is important as well, because it leads to school adjustment, motivation, cooperation (Vedder et al, 2005).

Students differ in the social support they need. For example in a concrete learning situation, those students for whom performance is very important are more satisfied when they can show how well they have done without any help. In these learning situations help may indicate low competence (see attribution theory), that is why some students object to help while doing school tasks. Those students, who consider social support as important and perceive that support in school, will be satisfied with the school environment. However, those students, who do not feel that they are supported, although they need it, will report low well-being (Vedder et al, 2005).

Based on assessment and the management of learning, educational situations can be characterized as competitive, cooperative, and individualistic. Students evaluate themselves through their successes and failures, and also from other information that the environment can provide. In a competitive environment, where rewards are limited, social comparison is more present. The role of peers is highlighted, because the students' self esteem depends on how he or she performs relative to the others. An individualistic context forces the student to focus on him or herself, every student can be successful regardless of the others' performance.

In a cooperative classroom students depend on each other in their successes, failures, development. They are forced to work together, they are forced to view each other as partners, pals. The performance of the whole group influences the individuals' self-evaluation.

If you think back on your school experience, in what kinds of context have you had the chance to study (competitive, cooperative, individualistic)? How did it/them influence your achievement, well-being, friendships?

1VEDDER, P., BOEKARERTS, M., SEEGERS, G. (2005). Perceived social support andwell being in school; the role of students' ethnicity.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 269–278.

The educational context influences what pieces of information affect the students' self-esteem. Success is evaluated relative to the social context. In a competition the same performance is valued more than in a non- competitive situation, since it is labelled as a triumph, a victory. In case of a failure the situation is similar, since devaluation is more obvious, compared with the situation where the student performs weaker than usual. In a cooperative context all students-regardless of their usual achievement-are satisfied or dissatisfied with group performance. Competition creates a context in which students differ strongly in their perception of each other, and also how they are perceived by others. For example teachers's evaluation is more extreme regarding high and low achievers in a competitive classroom than in a cooperative classroom (Ames, 1984)2.

Empirical studies show that the changes of the educational context (from starting school at 6 or 7 until leaving the system as young adults) do not adapt to the developmental changes of students. According to Eccles and Midgley (1989)3 this lack of stage-environment fit peaks in adolescence, when students change school and they go to either middle school or junior high school. The authors highlight some elements that cause this lack of fit between personality development and social and educational context. One such factor is the above mentioned emphasis on competition and social comparison, although as student get deeper into adolescence their need to focus on the self, to understand their own personality, to investigate their identity increases. The educational context offers limited opportunities to decide and choose, although the need for autonomy increases. Also, Eccles and Midgley draw attention to social network that surrounds students: peers disappear with a school change, relationship with teachers becomes more official and less intimate than it was during the first school years.

Although Eccles and Midgley regard competition as a negative context both for the individual and the group, today competition's judgement is less one-sided. One of the most important functions of competition is motivation. Still, it is true that one of the factors that determine classroom climate is the way differences between students are handled. If competition leads to the preference of some students over the others, it can cause interpersonal conflicts beyond the personal. The norms that are connected to competition can build as well as ruin the community in the classroom. If the competition is solely about triumphing over the others, that will certainly lead to conflicts among classmates. If competition is used as a method to help each student in their development, it is more likely to preserve good relationships.

2.2. Social support and achievement

Carol Goodenow (1993)4 studied the connection between motivation and social support in early adolescence.

Exploring social support, intrinsic motivation and expectations and values concerning efficacy, she found that perceived teacher support was the strongest predictor of expectations, and expectations were the strongest predictors of intrinsic motivation. No relationship between peer support and efficacy was found. General social support was found to be better predictor of good achievement than intrinsic motivation. This latter result is especially important because the literature on motivation in education without exception agrees on the unique role of intrinsic motivation in effective learning.

2AMES, C. (1984): Competitive, cooperative and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive-motivational analysis. In: Ames, R. E., Ames, C. (eds.): Research on Motivation in Education. Student Motivation. Vol. 1. Academic Press. 177-207.

3ECCLES, J. S., MIDGLEY, C. (1989): Stage-environment fit: developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. In: Ames, C., Ames, R. (eds.): Research on Motivation in Education. Goals and Cognitions. Vol. 3. Academic Press. 139-186.

4GOODENOW, C. (1993): Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: relationships to motivation and achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 1. 21-43.

Patrick et al (2007)5 studied the role of perceived peer and teacher support in mastery motivation, self-efficacy.

Goodenow's results suggest that when students feel the emotional support of their teachers, they get more engaged and are willing to put more effort into learning. It is logical that teacher support increases students' motivation, but what about peers?

In what ways have your classmates, friends, peers supported your learning in school?

From the changes that take place in the development around adolescence it is important to highlight that around the age of 9-10 children rely more and more on their peers, and relationships with adults begin to be more spacing. Therefore perceived peer support can also have an effect on school performance and achievement.

Patrick et al (2007) presumed that by increasing self-esteem and reducing anxiety peers help engagement in school work, and as a consequence of that, success in school. Although the authors do not mention, it is important to take norms and values into consideration. Peers can only have such an effect if in that particular context learning, effort and knowledge are positively valued. In case the norms are against learning, peer support leads to the avoidance of school work.

Kathryn Wentzel (1998)6 presumed that social support has a role in adaptation to school, because it helps students to overcome negative effects of stressful experiences (for example it is much less stressful to give an answer in front of the whole class in a supporting environment), so social support leads to an optimal general functioning. In her study, Wentzel found that teacher support is an independent positive predictor of interest toward school, and interest toward the subject. Peer support predicts only pro-social goal setting (this result can be very important when it comes to bullying intervention programs). Parent and peer support have indirect negative effect on interest through distress. It means that the lack of parent and peer support causes so much stress for the individual that he or she loses interest in school work, which leads to maladaptive behaviours.

Still, teacher support may compensate that effect by promoting engagement for students, as Wentzel (1997)7 found this result in an earlier research. In general, adolescents perceive parents as more important providers of social support than either teachers or peers, but in an educational situation the teachers' role is more important, both with respect to academic achievement and well-being (Vedder et al, 2005)

Lisa Legault (2006)8 and her colleagues studied the question of social support from another perspective.

They asked why students are unmotivated in school. They studied the relationships among different variables:

amotivation, academic performance, self-esteem, teacher-, parent-, peer support, attachment. They have found that lack of attachment to peers, teachers and especially parents is associated with amotivation due to lack of values. Amotivation is in negative relationship with all kinds of social support. Legault and her colleagues suggest that there should be a shift toward studying emotional support, because their research showed that teacher support has an effect on competency, parent and peer support unfold their effects through attachment.

Vedder, Boekaerts, and Seegers (2005), on the other hand, have found that teacher emotional support was important predictor of school adjustment for both Dutch and Turkish/Moroccan students.

5PATRICK, H., ALLISON, M., KAPLAN, A. (2007): Early adolescents' perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 1, 83-98.

6WENTZEL, K. R. (1998): Social relationships and motivation in middle school: the role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 2, 202-209.

7WENTZEL, K. R. (1997): Student motivation in middle school: the role of perceived pedagogical caring. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 411-419.

8LEGAULT, L., GREEN-DEMERS, I., PELLETIER, L. (2006): Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 3, 567-582.

So far we have seen that the social context in school is important in at least two ways. On the one hand school is a place where achievement is sought, and the social context is also the context of learning. Therefore it is important to understand how the environment that is shaped both by teachers and the students themselves affects achievement, which is the most evident measure of school adaptation. Here we have seen how competitive, individualistic, and cooperative environments form performance and self-esteem. Also, we have seen how developmental changes and school changes divert, causing a problem of stage-environment fit in adolescence.

On the other hand, studies showed that support from parents, teachers and peers help a more adaptive functioning in school. Without social support students do not even try to achieve, therefore their chances for success decrease greatly. In the next part of this chapter we take a closer look at peer support through a phenomenon that is unfortunately prevalent in nearly all school classrooms (Smith and Brain, 2000)9, and that is bullying.

2.3. Bullying as a social phenomenon: the role of peer support

School is not only a place of the kind of peer support where students help each other in their studies and support each other when somebody is in trouble, but also a place of the kind of peer support where students assist each other in harming others. Often students laugh together at (and not with) one or more classmates, often they exclude one or more classmates from the community, often they participate actively or passively in causing physical or psychological harm to someone. Literature considers peer aggression bullying when three characteristics can be associated with the act: intentionality, harm, unequal power relations. It means that an aggressive action against another student is only considered bullying, when the aggressor intends to harm the other, who is weaker in one way or another (physically weaker, lonely, etc.).

See video: Defeat the Label Anti-Bullying [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o7nxbULcaH4]

Researchers tend to approach the phenomenon of bullying from the perspective of the personality and from the perspective of group mechanisms. Before we turn to our main topic and explore the social aspect of bullying, let us consider some aspects of personality. Students often become victims of bullying because they have some external traits that make them different from the others: too fat, too slim, wears glasses, has red hair, etc. The problem with these external characteristics is that they cannot be generalized, because the most important traits that may make a student a victim are internal traits. Victims are socially isolated, have low self-esteem, are more anxious, cautious, sensitive, and have difficulties with communication. They long to be accepted and be loved.

Bullies have a high need for dominance, low empathy, are impulsive and have low self-control. Social power is very important for bullies they feel satisfaction when they see the victim suffer (Olweus, 1993)10. Bystanders belong to different types, basically they have three different attitudes to bullying: some of them support- actively or passively-the aggressor, some support the victim, and some do not care about it. The characteristics of the bully-supporter bystanders are similar to the bullies, they also have high need for social power. The characteristics of the victim-supporter bystanders are high empathy and secure attachment with mothers (Nickerson, Mele and Princciotta, 2008)11.

9SMITH, P. K., and BRAIN, P. F. (2000). Bullying in schools: Lessons from two decades of research. Aggressive Behavior, 26(1), 1–9.

10OLWEUS, D. (1993): Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell, Cambridge, MA.

11NICKERSON, A. B., MELE, D., PRINCIOTTA, D. (2008). Attachment and empathy as predictors of roles as defenders or outsiders in bullying interactions. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 687-703.

Characteristics of personality are only pieces of information with respect to understanding the phenomenon of bullying. According to Salmivalli, Lappalainen and Lagerspetz (1998)12 a preadolescent's behaviour in a bullying situation is more like his or her peers than his or her previous behaviour in similar context. Several empirical studies confirmed peer role in bullying (see Gini, 2006)13, and at least six different roles can be taken up by those participating in it: victim, bully, bully reinforce, bully assistant, defender of the victim, outsider.

Salmivalli, Huttunen, and Lagerspetz (1997) have found that group behaviour has a strong influence on an individual1s behaviour in a bullying situation. Research on attitude towards bullying has revealed that generally students disapprove of bullies and sympathize with victims. However, unfortunately as children grow older and reach adolescence, their attitude changes in a more pro-bullying direction (Gini, 2006). Fortunately, in the last decade hundreds of campaigns address the problem of bullying, with the direct and articulated aim of drawing attention to and highlighting the issue.

See video: Cyberbullying PSA [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpQuyW_hISA]

Another social aspect of bullying is intergroup conflict. In order to understand this aspect of bullying, we need to turn back to Tajfel's social identity theory, which proposes that individuals' behaviours, attitudes towards, and perceptions of in-group and out-group members derive from their desire to belong to a superior group in order to enhance their self-esteem. Obviously this leads to a preference of the in-group and the members of the out-group are seen as different, and may be discriminated against. Group members are likely to develop discriminating attitudes, when their identification with the in-group is strong, when the in-group has norms encouraging out-group bullying, when they think their status is increased by out-group derogation, and when they believe that they are threatened by the out-group (Gini, 2006).

12SALMIVALLI, C., LAPPALAINEN, M., and LAGERSPETZ, K. (1998). Stability and change of behavior in connection with bullying in schools: A two-year follow-up. Aggressive Behavior, 24(3), 205-218.

13GINI, G. (2006) Bullying as a social process: The role of group membership in students' perception of inter-group aggression at school.

Journal of School Psychology, 44, 51-65.

Gini (2006) explored in a qualitative study perceptions of a physical bullying episode involving their own class against another. Students (average age: 12) consistently preferred the in-group against the out-group, attributed more blame and punishment to the out-group, regardless of the teacher's presence. The author concluded that preadolescents are more affected by inter-group dynamics than contextual factors when they are participants in a conflict which involves bullying.

2.4. Bystanders' role in the act of bullying

Through socialization, children learn different patterns of behaviour. They learn how to express feelings, how to react to others' behaviour, how to get into contact with others, and so on. One important mechanism to learn is imitation: they observe the social environment and then imitate what they see. In this process the social environment plays very important role: parents, sisters, brothers, neighbours, friends, teachers, peers, and all the important persons are models who influence attitudes, behaviours, feelings. Besides socially favourable behaviours, aggressive and antisocial behaviours are also subject to social influence, among others, peer influence. Literature on peer selection suggests that aggressive children and adolescence not only influence, therefore encourage each other, but also choose each other as friends (Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta, 2011)14. Thomas and Bierman (2006)15 have found that long lasting exposure to high levels of classroom aggression predicts future aggressive behaviour.

At this point the question may arise: what about those children who do not show aggressive behaviour but are part of the peer group, that is, they are also members of the class. How do they influence aggression within the group? This is a question that literature on bullying started focusing on in the last decade. Bullying

"involves incidents that are witnessed by large audiences of normative peers" (p. 669, Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta, 2011), who do not participate in the act, but indirectly must influence it one way or another.

Bystanders may support the bully, agree with the aggressive behaviour, they may object or reprove of it, or they may be totally indifferent about it. The important task is to explore how these attitudes influence bullies and victims. As Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta (2011) argue, unfortunately not many empirical researches have been done to explore how witnesses or bystanders actually affect bullying, although models of bullying intervention address the idea that it is important to change bystanders' behaviour. Especially classroom-level intervention programs focus on bystanders.

Salmivalli and colleagues (1996)16 identified different participant roles besides bullies and victims in the bullying process. Assistants of bullies are those students who actually join the ringleaders, take an active role. Reinforcers support the bullies, provide positive feedback, like cheering, laughing, clapping. Outsiders withdraw from the situation, they seem to be indifferent about it. Defenders take sides with the victims, show empathy or make steps to protect or support the victims.

De Rosier and colleagues (1994)17 observing 7 and 9-year-old boy groups have found that when members of the group sided with the victim, the level of teasing, verbal disagreements increased. Pepler and colleagues

14SALMIVALLI, C., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behaviour in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 668-676.

15THOMAS, D., and BIERMAN, K. (2006). The impact of classroom aggression on the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 471–487.

16SALMIVALLI, C., LAGERSPETZ, K. M. J., BJORQVIST, K., OSTERMAN, K. ÉS KAUKIAINEN, A. (1996): Bullying as a groupprocess: Participant roles and their relations to social status within group. Aggressive Behavior, 22. 1–15.

17DEROSIER, M. E., CILLESEN, A. H. N., COIE, J. D., DODGE, K. A. (1994). Group social context and children's aggressive behaviour.

Child Development, 65, 1068-79.

(Craig and Pepler, 1997)18 have done observational studies and found that from the instances when victims were provided support 57% were effective at putting an end to bullying within 10 seconds.

The bystanders' behaviour can function as social rewards or punishments for the bullies. What is more, often bullies select the right place for the attacks, because they want to increase the chance of demonstrating their power, and also show and ensure their prestige within the group. Bandura's social cognitive learning theory (1973) explains this phenomenon by stating that bullies learn to anticipate such rewarding consequences of their behaviour, which leads to the repetition of it more and more often. In contrast, if the bullies are challenged again and again by facing bystanders supporting and protecting victims in the bullying, that will lead to the end of bullying, because bullies experience that this is not the right way to reach social power, status and prestige.

The issue of bystander effect is important, because of several potential reasons. On the one hand, their behaviour is probably easier to change than that of the bullies. On the other hand, if bystanders are encouraged to support the victim, the social rewards associated with bullying would consequently decrease, or diminish. Yet, it is not clear how these group and interpersonal dynamics work (Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta, 2011).

One of the first, if not the first, studies to explore the association between reinforcing and bullying was done by Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta in 2007. Eventually they have collected data from 77 schools, 388 classrooms, 7257 students (grades 3-5, ages 9-11) in Finland. Students filled out Internet-based questionnaires measuring self-reported bullying, bystanders' behaviours, antibullying attitudes and empathy toward victims.

They have found that the frequency of bullying in a classroom was negatively associated with defending and positively associated with reinforcing. There was a difference in the magnitude of the effects of bystander behaviour. The study revealed that bullies are more sensitive to the positive feedback provided by their supporters than to the negative feedback provided by the supporters of the victims. However, the authors indicate that this difference may be due to the ways of supporting victims, since there were items in the questionnaire that referred to such defending behaviours as comforting the victim. Some protecting behaviours are not salient and bullies may not be aware of them. Another reason for the difference may be that the reinforcers are not merely peers but also friends, and feedback from them is even more significant. Also, the authors emphasize that defenders, even if their influence is less effective on bullies, have a very important role in indicating that the victim is not alone, which is more favourable than experiencing rejection from the whole class (Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta, 2011).

The most important implication of the above presented study is that intervention programs should just as well focus on whole groups, especially classes, as individual bullies and victims. Supporter bystanders should be encouraged to use salient forms of protection to make bullies aware of the fact that victims are not alone. Based on the results, reducing reinforcement is most likely to lead to a decrease in bullying in the classrooms. There already is evidence that intervention programs aiming at reducing reinforcing behaviour, enhancing empathy and self-efficacy to defend are successful when whole classes are involved (Frey et al., 2009)19.

Much has been told about why children become bullies, why they become victims, but less research has been done on why bystanders decide to defend the victim (Thornberg et al., 2012)20. From the perspective of social psychology and group dynamics it is much easier to explain why bystanders reinforce the bullies. If the bullies

18CRAIG, W., PEPELER, D. (1997). Observations of bullying and victimization in the schoolyard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 13, 41-59.

19FREY, K. S., HIRSCHSTEIN, M. K., EDSTRÖM, L. V, SNELL, J. L. (2009). Observed reductions in school bullying, nonbullying aggression, and destructive bystander behavior: A longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 466–481.

20THORNBERG, R., TENENBAUM, L., VARJAS, K., MEYERS, J., JUNGERT, T., and VANEGAS, G. (2012). Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: to intervene or not to intervene? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13 (3), 247-252.