FINANCIAL CRISIS AND THE CHANGE

IN THE PRACTICE OF APPLYING COMMON CHARGE COSTS

TAXATION AND THE CRISIS

Slowly we are nearing the end of the economic crisis that evolved in 2008, and today we are able to soberly sum up the experiences and draw the consequences. To do this the saying incites: “Who does not learn from history has to live through the events repeatedly.”

The European Union – despite the well palpable prognostics – was surprised by the world economic crisis. At the beginning it was not easy to even diagnose the cri- sis: some saw the temporary functioning problems of the financial sector in a geo- graphical location, others believed to be able to keep the market tendencies under control by intensified interventions on a governmental level, however in no small number there were those who saw behind the phenomena and identified the mal- function of the international network of institutions as a result of the activity of the multinational companies in contrast to that of the governments, which were limit- ed to operate within national borders. Today we know well that the situation is even more complex and we are the contemporaries of a modernization process, a change resulting in the relocation of economic centre of gravity and one preparing for the reform of the institutional system, in parallel.

The problems at first were referring to the repeated misfunctioning of the mon- etary system, however, the permanent shakiness of corporate financing did not leave the competitive sector untouched either. As a consequence, the symptoms of over-production crisis became identifiable (see the case of the automotive indus- try). The contradiction between production and demand were sensed in the fall- back of foreign trade relations, though contradictions between the solvent demand exceeded by product supply also appeared on domestic markets in a short time.

Initial steps taken for the recovery of balance were targeted at first to curb produc- tion (stopping of conveyor belts, forced holidays, shortened working hours), fol- The global financial crisis has not left the members of the EU untouched.

Financial results have significantly dropped, businesses were folded in great numbers, the rate of employment decreased, social tension got fortified, and so did the national deficits in the budget in the majority of the countries. The decisive members of the community reacted fairly quickly to the challenges of the global economic crisis, and among the steps taken there were simultane- ously ones to boost the economy and others to lower the expenses of the expen- diture. The author examines what role was given to the steps in taxation poli- cy as indirect regulating tools, and that how the decisions brought touch upon the previously issued harmonization strategy.

lowed by cutbacks, to be followed in a very short time by social tension. All this was topped by – including the Euro – the hectic movement of exchange rates.

International organisations – like the European Union – in the beginning were quiet observers of the developments, and, regarding the fact that the effects of the crisis were first appearing within the frames of national economies, these govern- ments were the first to indentify the need for immediate action – their solutions being similarly of national character. Several countries – over-censoring the EU reg- ulations for support – saw the solution in the state-level furtherance (see: upgrading of capital stock) and the artificial vivification of demand. In order to achieve this

Source: EUROSTAT database, calculations of author

Figure 2. State income and expenditure in ratio with GDP in the EU27 countries, in 2008 Source: European Commission - Interim forecast February 2010

Figure 1. Real GDP growth rate in the EU countries (percentage change on previous year)

taxes on consumption were toned down (see: UK), or the extension of state support for purchases (see: Germany).

For other countries – due to previously agglomerated indebtedness and various other reasons – this tool was not available, moreover, as a result of the deteriorating financial results and dwindled revenue income they were forced to introduce robust steps in cutting back expenditure as a whole (see figure 2).

As a natural consequence, the relinquishing from taxes, and the increase of the state support against budget, budget deficit and with their accumulation state debts scampered. Relatively quickly it became obvious that the effects on fiscal policy are far from being temporary, and can be handled within national frames for a transito- ry period only.

The majority of the EU member states launched the modernization of the com- mon charge cost systems a long time before, however, whereas the earlier pro- grammes were based on concepts “rooted in recognition”, those corrections aiming at extenuating the negative effects of the economic crisis can rather be considered as ones based on short term considerations brought under pressure.

The concepts evolving from the second part of the 90s, based on recognition and aiming at the modernization of the taxation system were in the first place serving the idea of giving an impetus to economic outputs, and a more even distribution of burdens (to reorganize tax burden from those with lower incomes onto those with- in the higher income bracket), and the steps very strongly identical can be put into 6 groups[Sanford 1993]:

a) the depression of increasing tax avoidance(wickets) and tax fraud; and the expectable improvement of tax morals;

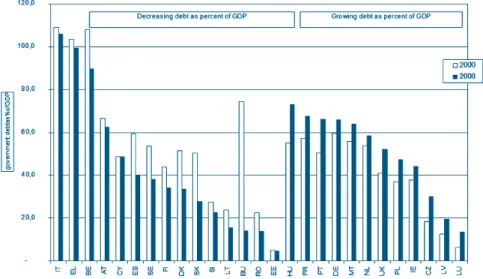

Source: EUROSTAT database, calculations of author

Figure 3. The changes in the consolidated debt amount related to GDP in the countries of EU27

b) the mitigation of the relatively high taxation rates, which have a counter effect on justice, regarding that those in the higher income bracket can more easily avoid taxes through a better knowledge of the regulations;

c) through a revision of the tasks placed on the state the desire was to limit the size of the public sector(see the gradual increase of tax and revenue income measured in relation to GDP);

d) it was planned to ensure the distorting effect of inflationthrough the 'mainte- nance' of the levels of taxes, regarding the fact that inflation, prevailing in a wide range has the objectionable consequence that un-indexed (valorised) tax systems re-group incomes in favour of the state (budget);

e) due to internationalisation of players in the economythe individual countries have to comply with global trends and when formulating the characteristic fea- tures of the functioning of their tax system, countries have to consider prac- tices of other states;

f) in the interest of the development of relations within the community and the minimization of effects curbing the market – besides respecting the national sovereignty – regulations of common charge costs have to be placed on an identical theoretical basis, or rather in the case of taxes on international ship- ments the pace of harmonization has to be speeded up.

The concepts that evolved from the mid-90’s were based on the idea that in cases when major changes take place in the structure of the economy, in the inter-relation of the branches of production, in the methods of production and marketing and in consumption, agglomeration and the employment structure of the population, then the basic components of the central economic regulatory system – within this the focal points of common charge costs, tax bases and measures and the rules of pro- cedure – have also got to be modified.

However, any change taking place in the system of common charges is the source of endless clashes of interest, regarding that the functioning of taxation systems touches upon several theoretical questions, and it can result in a basic rearrange- ment in the positions of players in the market. The pros and cons concerning mod- ernisation can be grouped into categories based on their symptoms:

Those on the side of social optimum, who observe the practice of changing the common charge cost system from the point of view of all concerned and not subdued to partial interest;

The one built upon political philosophy – to vindicate political ambitions and/or increasing chances at times of elections;

Ambitions concentrating on rent seeking, which typically represent partial inte- rests and are of ad hoc nature – and disregard contexts of the macro economy.

Posteriorly evaluating one has to state that those concepts for the modernisation of the taxations system that were based on recognition – within them opinions urging the ones related to community harmonisation – did not receive the necessary sup- port, and as a result, instead of the sonorous reforms we had to be satisfied with cor- rectional steps on a much smaller scale, which had far less significant effect on a social and economic level.

In the lack of social and economic support corrections to a minor scale took place in the majority of the countries of the EU-27, which, on the whole did not

reach the critical mass, and to which the tax burden calculated in ratio of the GDP, or the distribution of the burden could have been modified in merit. The conse- quences are widely known: the stagnation of economic results, the deterioration of employment rates, stronger social tensions, the existence of deficits in the budget jeopardizing the pact on stability and development and the lurch of the common money.

The world economic crisis in 2008 – comparable to an earthquake(which can be called by various names depending on one's temperament, as the crisis of financ- ing, monetary crisis, economic crisis, crisis of modernisation, crisis of model) has resulted a basically new situation in public policy, and has not left the common charge cost system untouched either:

1. Decrease of GDP, deteriorated results, termination of companies, cessation of workplaces, decrease in national incomes;

2. The mitigation of the negative influence of the economic crisis on a state level induced intervention on that level – which, in the lack of own resources – went together with the mobilization of external sources. This, however, naturally resulted in the growth of internal and external debts;

3. Debt is protracted taxthat has to be paid back following stabilisation, in other words the tax policy in the years following stabilisation and the level of tax bur- den measured in relation to the GDP move along a pre-determined direction (the tax burden of today, in lack of agreement between the generations – can- not be shifted over to the forthcoming generations).

All in all, in the securing of the balance of the state budget tax and revenue incomes were valorised, and against the hoped mitigation of common charge costs – due to regulations brought under pressure – it is a relatively and permanently high level that will prevail. This does not mean though that a structural modification in the tax and revenue charges cannot take place, on the contrary, this is point-blank desirable, but the burden as a whole – until the catching-up with the growth trend before the economic crisis – can hardly be lessened.

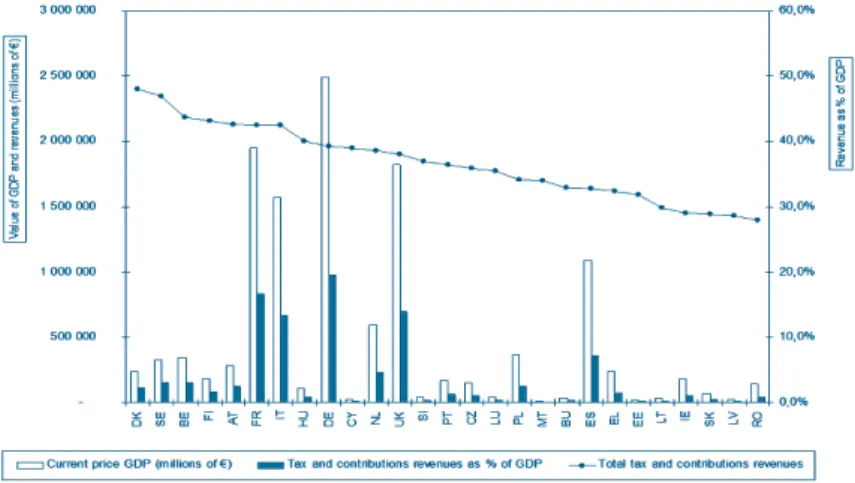

Source: EUROSTAT database, calculations of author

Figure 4. Tax and revenue income in relation with the GDP in 2008

The size of tax and revenue burden is usually measured in a percentage ratio to the GDP, so based on the average of several years – we can differentiate countries with high, average and low tax burden.

a) Countries in the high revenue bracket: Denmark (48.0%); Sweden (46.9%);

Belgium (43.7%); Finland (43.1%); Austria (42.6%); France (42.5%); Italy (42.5%)

b) Countries in the average revenue bracket: Hungary (40.1%); Germany (39.3%);

Cyprus (39.0%); Netherlands (38.5%); United Kingdom (38.0%); Slovenia (37.0%); Portugal (36.5%); Czech Republic (35.8%)

c) Countries in the low revenue bracket: Poland (34.1%); Malta (34.0%); Bulgaria (32.9%); Spain (32.8%); Greece (32.3%); Estonia (31.8%); Lithuania (29.8%);

Ireland (29.0%); Slovakia (28.8%); Latvia (28.6%); Romania (27.9%).

The tax and revenue burden measured in percentage ratio to the GDP is a telling figure, but it does not represent how much each country's budget depends on the realisation of the tax and revenue income. This area is revealed by the ratio of the tax and revenue income within the budget incomes, and this also indicates how much a nation – without the changes in the expenditure side – can change the rates of tax and revenue with no consequences to follow.

Based on the figures of 2008 – depending on the ratio of the tax and revenue income within the budget incomes – the EU27 countries can be categorized in sev- eral groups:

a) Countries strongly dependant on tax and revenue income are those, where within all budget income their ratio is 90% or more (see: Italy, Germany, The United Kingdom, Cyprus, Belgium, Slovakia, Spain);

Source: EUROSTAT database, calculations of author

Figure 5. The ratio of tax and revenue income in all state budget income in the EU27 countries in 2008

b) Countries dependant on tax and revenue income to a medium levelare those where within all budget income their ratio ranges between 85–90% (see:

Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovenia, Denmark, Romania, France, Poland and Estonia);

c) Countries relatively less depending on tax and revenue income are those where their ratio within all budget income does not reach 85% (see: Sweden, Malta, Portugal, Bulgaria, Ireland, the Netherlands, Latvia, Finland and Greece).

The figures in 2008 – as a whole – show that in nearly two thirds of the EU coun- tries the budget execution is strongly related to the tax and revenue income, that is, the effectiveness of the common charge cost system very important* The efficiency of operation depends on a lot on the conditions. Such is, among other things the index of tax and revenue burden in relation to GDP, the quality of services provid- ed by the state, the size of international relationships, the calculability of the legal environment, the practice of voluntary compliance etc.

For handling the deficit in the budget there are more than one methods in theo- ry: one of them is to keep the tax and revenue burden as percent of the GDP on a high level; another – through exploiting the possibilities hidden in international co- operation – is the improvement of the efficiency of common charge systems; the third is the gradual inflating of the budget deficit. None of the methods are perfect, or rather none of them promise a spectacular result in the short run.

*The author deals with the measuring of effectiveness of common charge cost systems in his study pub- lished in Public Finance Quarterly, 2010/1.

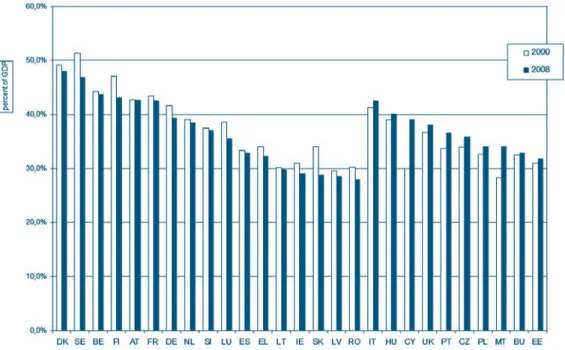

Source: EUROSTAT database, calculations of author

Figure 6. Shift of Tax to GDP ratio between 2000 and 2008 in the EU-27 countries

From the point of view of creating the optimal level of common charge costs the countries of the EU 27 squirm in the trap of “Catch 22”: on one hand, in the interest of improving competitiveness in the market for companies the deductions in ratio with the GDP should be reduced, but it contradicts with the deficit developing in the budget, and the duties in debt service. Naturally, another solution could be the curbing of state expenditure but this would not result in a spectacular cut back of debts and the narrowing down over again of prosperity services (the derogation of acquired rights) could go together with unpredictable social effects.

Based on Figure 6it can be stated that in years 2000–2008 in nearly two thirds of the EU27 countries the level of tax and revenue burden was remitted, whereas in somewhat more than one third it increased. Regarding the fact that in the “old mem- ber countries” providing nearly four fifth of the economic performance the modifi- cation in tax and revenue burdens was relatively insignificant, on the whole the average tax burden in the countries of the EU27 was hardly modified. In order to realistically qualify the situation it has to be disclosed that the tax burden in the main competitor countries, the United States and Japan is lower by 10–11 percent- age point and that of China, the new competitor that strives to acquire the market positions is 20 percentage points lower than in the countries of the EU27. In other words it means that for the countries in the EU to remain a competitor on the mar- ket solutions are a requirement to boost integration performances, and to ease the burdens in general for the competing sector.

CORRECTIONS TOUCHING UPON THE TAX AND REVENUE SYSTEM IN THE COUNTRIES OF THE EU27

The main pursuits of those programmes aiming at correcting the tax and revenue system due to the economic crisis in 2008 as a forcing circumstance (which basical- ly are of structural nature and leave the tax and revenue burden related to the GDP untouched) can be summarized in the following:

The modification of the structural characteristics of tax and revenue burdens within the taxation system (see VAT, green taxes) and also the expansion of the role of indirect taxes;

The broadening of the basisfor personal and company income tax;

In the case of private individuals it is for inciting productivity and for compa- nies to fortify the ability to attract and keep capital the lowering of keys in income taxes;

A gradual decrease in the tax and revenue burdens on labour in order to improve international marketing abilities and indices of employment;

The simplification of tax proceduresand decreasing of administrational burdens;

The improvement in the efficiency of the operation of the tax administration, to minimize the gap between the taxes collected and achievable.

Above the general characteristics it is worth to present some of the efforts of indi- vidual member countries reflecting special features:

a) Germanydeserves special attention, as preceding the turn of the millennium a 7-year programme for economic expansion has been elaborated with a sched-

ule to completely modernize the tax system with an annual breakdown of the period. Within this frame the PIT marginal keys are mitigated (from 53% to 42%

and from 25,9% to 15%) and those of the social tax (from 40% to 25% and later to 15%), and the cutting back of the burden on labour. The 38% property tax was ceased and the modernization of autonomous taxation was launched.

Against the positive changes huge debate was generated on the introduction of taxation on portfolio-investment (10%), that of compulsory minimal tax for companies, the generalisation of tax on capital income, and the increase of the normal key of 16% of VAT to 19%, together with the initiative role in the spread- ing of green taxes;

b) Spainis widely known as a country with low taxes, and within this the level of direct taxes lower than the EU-average has a decisive role. The changes touch- ing upon the system of common charge costs have two directions: on one side they relate to income taxation (the increase in the number of tax bands, at the same time the widening of the sphere of allowances, in social taxation the less- ening of company burdens; on the other side the increasing of the normal 16%

VAT key to 18%. As from an international point of view a remarkable step is the decentralisation of state administration, and in harmony with this the modifi- cation of the ratio of regional levels in taxes (the local proportion of receiving the income tax rate is 33% out of PIT; 35% out of general income tax and 40%

out of VAT); just as well as an also courageous step as it looks is the legal guar- antee for these ratios;

c) Ireland– the system of common charge costs – earlier the most dynamically growing and most inventive country in the community – is undergoing an end- less transformation. The Irish economy earlier belonged to those with a low taxation (12.5% of social tax, the large preferentialism of the processing indus- try and the wide application of allowances of offshore nature), however, in par- allel with the deterioration of budget indicators strict measures were brought.

The normal VAT rate was increased by 0.5%, and the upper rate of PIT was raised from 41% to 46%. In order to improve the budget balance further mea- sures to curb expenditure were brought to light, such as the limitation of expenses in the public sphere by 5–15%, the retirement age was lifted to 66 years and decision was made to stop large scale investment projects;

d) Sweden's characteristics differ from those of other EU-members in various ways. Due to the 1991 taxation reform upgraded at the turn of the millennium the consumption taxes and those on labour are the highest among the mem- bers, and a dynamic growth can be seen in the tax burden on capital incomes in the past few years. As a consequence of all these the welfare society is encumbered with significant tension (the high level service cannot be financed from the income from contributions, however, tax burdens cannot be further increased without risking the competitiveness ), meanwhile the secur- ing of conditions for sustainable development require further investments. The now shaping changes in taxation – referring to the need for competitiveness – count on the curbing of burdens on employers and instead compensation will take place by the further lifting of taxation on activities representing environ- mental hazard and the higher contributions paid by employees.

e) Franceis in the middle of a battle on two fronts, because the improvement of competitiveness would require the mitigation of burdens on companies, how- ever, the increasing deficit in the budget indicates the need for further increas- ing taxes. In the years between 1995 and 2000 the incomes were more and more drained, social tax received a surtax of 10%, and the VAT rate was lifted temporarily from 18.6% to 20.6%. Within the French economic system a tax modernisation programme expanded for several years was accepted after the millennium. Its major elements are: the normal rate to VAT was reduced to 19.6% (in compensation revenue tax became higher), the tax burden on labour was decreased (with special regard to the low income band and those with the highest qualifications). As a result of the economic crisis new reform pro- grammes have been launched (in the first place to ease the burden on enter- prises), burden on live labour has been released, and in order to fortify willing- ness in enterprises the system of local taxation was corrected.

f) The Netherlandshas a somewhat lower tax burden in comparison to the coun- tries in the EU15, therefore the changes introduced following 2008 mean smaller corrections as against a comprehensive modernisation scheme. The changing of the PIT and the social contributions was aimed at the easing of tax burden (the lowering of the keys to the highest tax bands and the broad- ening of the tax-free band), and the lowering of the social tax key from 35%

to 30%. An increase of the normal VAT rate from 17.5% to 19%, the increase in the property tax behoving local administrations, and – alike in other coun- tries – the higher environment related taxes however have a counter-effect to the earlier.

g) Greececontinues with a practice completely different from the previous exam- ples, that is, from the point of view of the functioning of the common charge system can be considered as ‘still waters’. The tax burdening in ratio with the GDP – ranges between 32–33% on an average of the past few years, despite the fact that from among the member countries the deficit in the budget is the highest, or rather the consolidated debt amounts to the value of the annual GDP. One does not need special courage to express that this will not remain tenable in the long run, and the planned steps for 2010 – namely the reduction on health insurance expenses by 10%, the freezing of salaries above 2 000 euros for public servants, the introduction of taxation on capital income and the introduction of tax on property with high value – will be sufficient only for symptomatic treatment.

The overview of national reforms is far from complete, but it characterizes the steps for correction – often even of opposing directions. The hind thoughts remain not questioning the philosophy of a unified market, but it is hardly disputable that the actual steps made are based on short term concepts and serve national interest in the first place.

Meanwhile a growing number of experts give voice to the opinion that without the nearing of tax and contributions systems, operating as a tool for co-operation, the relations among the member states will take unwanted direction, and what is more, without moving towards fiscal federation the monetary federation can be endangered, too. Based on all these and the discretion of strategic interests the

member countries should, in the form of bi- and multilateral adjustments, take steps towards a gradual harmonisation of common charge system regulations.

COMMUNITY LEVEL TAX HARMONISATION – BICKERING APPROACH

The content of the reforms formulating within the national frames are deeply touched upon by the community programmesjust as well, despite the many unde- cided questions. It is by no means all the same whether a federative organisation will be created with the participation of the member states or the other organisational theory, the federation of national communities will operate. Serious changes can derive from the fact how many members the monetary union can enlarge to, or rather whether this union can be followed by a fiscal federation. If yes, then in the interest of the operability of the fiscal federation a fastened tax harmonisation will be unavoidable, moreover, in this case not only the structural composition of the tax systems (the unionisation of the pretences of common charge varying from 42 and 240 at the moment) but the definition of tax bases on identical theoretical back- ground has to be prepared.

Table 1. List of VAT rates applied in the Member States, 2009

Source: European Commission (Situation on July 1, 2009)

Member States Super Reduced Rate Reduced Rates Standard Rate Parking Rate

Belgium – 6/12 21 12

Bulgaria – 7 20 –

Czech Republic – 9 19 –

Denmark – 25 25 –

Germany – 7 19 –

Estonia – 9 20 –

Greece 4.5 9 19 –

Spain 4 7 16 –

France 2.1 5.5 19.6 –

Ireland 4.8 13.5 21.5 13.5

Italy 4 10 20 –

Cyprus – 5/8 15 –

Latvia – 10 21 –

Lithuania – 5/9 21 –

Luxemburg 3 6/12 15 12

Hungary – 5/18 25 –

Malta – 5 18 –

Netherlands – 6 19 –

Austria – 10 20 12

Poland 3 7 22 –

Portugal – 5/12 20 12

Romania – 9 19 –

Slovenia – 8.5 20 –

Slovakia – 10 19 –

Finland – 8/17 22 –

Sweden – 6/12 25 –

United Kingdom – 5 15 –

It is well known that the EU does not have income deriving from direct taxes, or rather the gross value of income rightful for the community, is a fraction in percent- age of the gross GDP figure in the EU27 countries. (As indicated earlier, on the level of member countries national budgets can possess 44–46% of the GDP, at the same time the budget of the European Union, in relation to the gross GDP amount of the members remains under 1.00%.) The contradiction is even larger if we consider that the member countries delegate an increasing number of tasks and duties to the EU, and intend to finance them to a lesser extent.

In preparation for the new budgetary cycle (2014–2020) contradicting concepts are being born among the EU member states:

The representatives of countries being in the position of net payersrepresent a standpoint where the duty of paying 1.00% of the total GNP value should be reduced;

At the same time those representing the support for deepening integration would find the increase of the contribution necessary, and they say that the duty of paying 1.00% of the total GNP should be increased by multiplying it with 1.5–to 2 in several stages.

It is almost beyond dispute that the EU has arrived to a crossroads. In case the com- munity considers the Treaty of Lisbon as still prevailing and wishes to close up to the leading countries of the world economy, then it has to speed up economic growth, has to improve the competitiveness of market players, has got to care for increasing the number of workplaces and must not relinquish the gradual falling into line of underdeveloped regions.Within the realisation of community targets a major role has to be played by the operational tax and revenue systems functioning as indirect regulators, and when modernising them attention must be paid to let them serve both community and national interests in parallel.

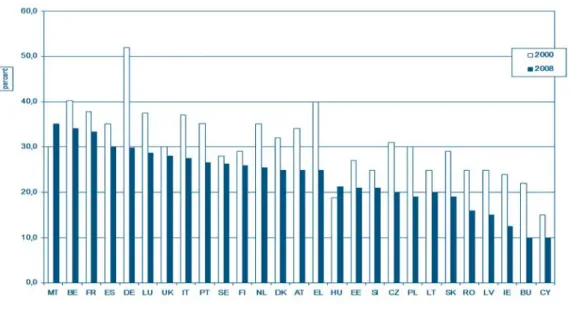

Source: EUROSTAT database

Figure 7. The changes of corporate tax rates between 2000 and 2008 in the EU-27 countries

The modernisation process of common charge costs formulates serious chal- lengesfor the community as well as for the individual members:

The ratio between tax income as against the GDP is high, and in comparison to other competitors the indices related to the labour force are especially dis- advantageous (see: employers’ burden on labour income, or rather the deduc- tions touching on employees);

If the EU intends to fully validate the principles of freedom then the difficulties curbing the functioning of unified market have to be completely removed(see:

the differences of taxation in tax base, tax levels and regulations of proceed- ings), and instead of fortifying internal competition external competitiveness has to be improved;

The acclimatisation of Euro as common currency and thus the enlargement of the Euro-zone has created a new situation from a number of aspects, among them the direct commensurability of such indicators as economic perfor- mance, profitability indices and tax burdens(see: the strengthening of efforts to minimise the differentiating effect of deviances from average);

The operation of companies bridging over national borders makes it obvious, that the individual countries are able to protect their interests against globali- sation exclusively through the improvement of international co-operation and the unifying approach of regulations on taxation.

The ‘demand for harmonisation’ appeared as early as in the Treaty of Rome for a community level common charging, however, its full implementation can be the result of an organic development alone. Today the vindication of national indepen- dence and responsibility are in the forefront of interest, but the first signs of needs for harmonisation have appeared and are being fortified. Proposals concerning changes hardly touch upon the current cycle, however, the preliminary skirmish for the shaping of strategic goals, the prioritised community programmes and the mechanism of financing for the budget period 2014–2020 have already begun.

a) It has to be worded as a demand for the new budget period that the system of goals and appliances be harmonised, in other words a financial background has to be created for the backing of community level programmes – one that is tailor-made for the feasibility requirements. This can partly be implemented by the raising of the membership payment responsibilities, partly by establishing a new type of tax based on a community decision and serving community pur- poses and partly, through the fortification of international co-operation, by the improvement of the efficiency of common charge systems;

b) The VAT system belongs to the so called harmonised forms of common charg- ing, however, as a result of the “budget interest” of individual member states a final agreement could not be reached. The new harmonisation has to include normal and preferential taxation categories, a more determining approach of taxation rates, the theory of paying VAT (see: switching over to accounting in the country of origin), and the regulations of operation. The fine-tuning of reg- ulation originates from the need that the different VAT rates have different influence on prices, which creates a difference in the competitiveness of the products and services (see Figure 6).A further contradiction is that based on the VAT calculation system of the country of destination the VAT to be paid

after the purchased product/service is calculated with the VAT rate of the coun- try of destination and be paid into that country's budget. Without a levelling mechanism it is especially disadvantageous for the exporting countries, but at the same time makes the defining of the VAT base of the “consumer country”, serving as the basis for the community payment, also irrelevant.

c) Changes in merit has to be reached in the taxation of companies organised on a network principle, stepping over national borders, with this improving the transparency of common charges, the tax base being calculated on unified principles, lessening the administrational burdens, and with the strengthening of the control-mechanism narrowing down the possibility of income and cost transferring (see Figure 7). The basic principles have been shaped, now it is the turn to put it in practice.

d) Labour force mobility in the EU27 countries has significantly grown, which goes together with the more urging need of community level harmonisation of social security systems. Old regulations are sufficient for the judgement of paying contribution fees and rights for services to an ever smaller degree. It is especially true for the practice of payment of pension contributions (in some countries the pension contribution paid in one’s active working life is exempt from PIT, whereas old age pension is subject to PIT, in other countries the sit- uation is the other way round), which can reach final settlement through the harmonisation of procedural regulations alone.

If we seriously intend to enjoy the benefits stemming in integration, then very con- sequently we have to stand up against the phenomena jeopardizing the effective operation of the unified market, or rather in order to let the advantages be enforced the operational principles of the tax and contribution system ensuring 90% of the budget incomes have to be harmonised. It has to be identified that safeguarding against the processes of globalisation, or protecting interests successfully against multinational companies developing on a network basis stepping over national bor- ders can only be achieved by strengthening co-operation among member states. It is high time to be confronted by the fact that the fortification of international co- operation is not a sacrifice, on the contrary: it is a national interest.

REFERENCE

Sanford, C. T. (1993): Successful Tax Reform, Bath: Fiscal Publications