www.elsevier.com/locate/euroneuro

REVIEW

Live fast, die young? A review on the

developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan

Barbara Franke

a,b,∗, Giorgia Michelini

c, Philip Asherson

c, Tobias Banaschewski

d, Andrea Bilbow

e,f, Jan K. Buitelaar

g, Bru Cormand

h,i,j,k, Stephen V. Faraone

l,m, Ylva Ginsberg

n,o, Jan Haavik

m,p, Jonna Kuntsi

c, Henrik Larsson

n,o,

Klaus-Peter Lesch

q,r,s, J. Antoni Ramos-Quiroga

t,u,v,w, János M. Réthelyi

x,y, Marta Ribases

t,u,v, Andreas Reif

zaDepartmentofHumanGenetics,DondersInstituteforBrain,CognitionandBehaviour,Radboud UniversityMedicalCenter,Nijmegen,TheNetherlands

bDepartmentofPsychiatry,DondersInstituteforBrain,CognitionandBehaviour,RadboudUniversity MedicalCenter,Nijmegen,TheNetherlands

cKing’sCollegeLondon,InstituteofPsychiatry,Psychology&Neuroscience,Social,Genetic&

DevelopmentalPsychiatryCentre,London,UK

dDepartmentofChildandAdolescentPsychiatryandPsychotherapy,CentralInstituteofMentalHealth, MedicalFacultyMannheim,UniversityofHeidelberg,Mannheim,Germany

eAttentionDeficitDisorderInformationandSupportService(ADDISS),Edgware,UK

fADHD-Europe,Brussels,Belgium

gRadboudUniversityMedicalCenter,DondersInstituteforBrain,CognitionandBehaviour,Department ofCognitiveNeuroscience,Nijmegen,TheNetherlands

hDepartmentofGenetics,MicrobiologyandStatistics,FacultyofBiology,UniversitatdeBarcelona, Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

iCentrodeInvestigaciónBiomédicaenReddeEnfermedadesRaras(CIBERER),InstitutodeSaludCarlos III,Spain

jInstitutdeBiomedicinadelaUniversitatdeBarcelona(IBUB),Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

kInstitutdeRecercaSantJoandeDéu(IR-SJD),EspluguesdeLlobregat,Catalonia,Spain

lDepartmentsofPsychiatryandofNeuroscienceandPhysiology,StateUniversityofNewYorkUpstate MedicalUniversity,NewYork,USA

mK.G.JebsenCentreforNeuropsychiatricDisorders,DepartmentofBiomedicine,UniversityofBergen, Bergen,Norway

nDepartmentofMedicalEpidemiologyandBiostatistics,KarolinskaInstitutet,Stockholm,Sweden

∗Corresponding authorat:DepartmentofHumanGenetics,DondersInstituteforBrain,CognitionandBehaviour,RadboudUniversity MedicalCenter,6500HBNijmegen,TheNetherlands.

E-mailaddress:Barbara.Franke@radboudumc.nl(B.Franke).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.001

0924-977X/©2018RadboudUniversityMedicalCenter.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

oDepartmentofClinicalNeuroscience,CentreforPsychiatryResearch,KarolinskaInstitutet,Stockholm, Sweden

pDivisionofPsychiatry,HaukelandUniversityHospital,Bergen,Norway

qDivisionofMolecularPsychiatry,CenterofMentalHealth,UniversityofWürzburg,Würzburg,Germany

rLaboratoryofPsychiatricNeurobiology,InstituteofMolecularMedicine,I.M.SechenovFirstMoscow StateMedicalUniversity,Moscow,Russia

sDepartmentofTranslationalNeuroscience,SchoolforMentalHealthandNeuroscience(MHeNS), MaastrichtUniversity,Maastricht,TheNetherlands

tDepartmentofPsychiatry,HospitalUniversitariValld’Hebron,Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

uPsychiatricGeneticsUnit,Valld’HebronResearchInstitute(VHIR),Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

vBiomedicalNetworkResearchCentreonMentalHealth(CIBERSAM),Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

wDepartmentofPsychiatryandLegalMedicine,UniversitatAutònomadeBarcelona,Barcelona, Catalonia,Spain

xDepartmentofPsychiatryandPsychotherapy,SemmelweisUniversity,Budapest,Hungary

yMTA-SENAP-BMolecularPsychiatryResearchGroup,HungarianAcademyofSciences,Budapest, Hungary

zDepartmentofPsychiatry,PsychosomaticMedicineandPsychotherapy,UniversityHospitalFrankfurt, FrankfurtamMain,Germany

Received 19November2017;receivedinrevisedform25June2018;accepted7August2018

KEYWORDS Developmental trajectory;

Treatment;

Comorbidity;

Cognitiveimpairment;

Genetics;

Adult-onsetADHD

Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivitydisorder(ADHD)ishighlyheritableandthemostcommonneu- rodevelopmental disorderinchildhood.Inrecentdecades,ithasbeenappreciatedthatina substantialnumberofcasesthedisorderdoesnotremitinpuberty,butpersistsintoadulthood.

Bothinchildhoodandadulthood,ADHDischaracterisedbysubstantialcomorbidityincluding substanceuse,depression,anxiety,andaccidents.However,courseandsymptomsofthedisor- derandthecomorbiditiesmayfluctuateandchangeovertime,andevenageofonsetinchild- hoodhasrecentlybeenquestioned.Availableevidencetodateispoorandlargelyinconsistent withregardtothepredictorsofpersistenceversusremittance.Likewise,thedevelopmentof comorbiddisorderscannotbeforeseenearlyon,hamperingpreventivemeasures.Thesefacts callforalifespanperspectiveonADHDfromchildhoodtooldage.Inthisselectivereview,we summarisecurrentknowledgeofthelong-termcourseofADHD,withanemphasisonclinical symptomandcognitivetrajectories,treatmenteffectsoverthelifespan,andthedevelopment ofcomorbidities.Also,wesummarisecurrentknowledgeandimportantunresolvedissueson biologicalfactorsunderlyingdifferentADHD trajectories.We concludethataseverelackof knowledgeonlifespanaspectsinADHDstillexists fornearlyevery aspectreviewed.Ween- couragelarge-scaleresearcheffortstoovercomethoseknowledgegapsthroughappropriately granularlongitudinalstudies.

© 2018 Radboud University Medical Center. Published by Elsevier B.V.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

1. Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neu- rodevelopmental condition that typically starts during childhoodor early adolescenceandis thoughttofollow a trait-like course. The clinical disorder is defined by age- inappropriate levels of inattention and/or hyperactivity- impulsivity interfering with normal development, or functioning,ofaperson.AlthoughADHDcarriesthestigma of being a consequence of modern lifestyle, the first mentioning of the syndrome dates back to the late 18th century(Faraone etal., 2015).Historically,ADHD wasde- scribedmainlyinschool-ageboys(Still,2006).Later,itwas

recognised that many girls have similar problems – yet often remain unrecognised and, consequently, undiag- nosed.Duringthepastdecades,ithasbeen demonstrated that ADHD is common in all countries studied (Fayyad etal.,2017;Polanczyk etal.,2014),andthat itseriously affectstheproductivity,lifeexpectancy,andqualityoflife throughout thelifespan of patients(Erskine etal., 2013).

Importantly, it took until the late 20th century before it couldconvincinglybeshownthatADHDalsoexistsinadults, and that continuity exists from childhood to adulthood (Woodetal.,1976)callingforalifespanperspectiveonthe

disorder,embracingclinicalcourseandpresentationaswell asaccordingresearchontheunderlyingneurobiology.

As discussedindetailinthisreview,theclinicalpresen- tationofADHDisveryheterogeneous,withawidespectrum ofseverityandsymptomsthatpartiallyoverlapwithother conditions.Infact,ADHDsymptomscanbeobservedtran- sientlynotonlyinpsychiatricdisorders,butalsoinsomatic diseases and physiological states,such as after sleep de- privation or during over-exhaustion (Poirier etal., 2016).

This complexclinical picture has led toa need todefine core diagnosticattributes of ADHD,such asage of onset, continuityofsymptomsandtheirappearanceundervarious circumstances,symptomcounts,andexclusioncriteria.Al- though thediagnostic criteriahave been revised multiple times, thecore clinicaldescription ofADHD hasremained essentiallyunchangedduringseveraldecades.Inthelatest version of theDiagnostic andStatistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),itissimplystatedthat“ADHDbeginsin childhood” and thatitoften manifestsitselfin pre-school age(APA,2013).Thisapparentsimplificationdoesnotimply thateverypersonwithADHDwillhaveanidenticalclinical picture,orthatimpairmentislinearlydependentonsymp- tomcountsorageofonset.

Unfortunately, the fields of research on childhood and adulthoodADHDhaveoperatedinrelativeisolation,mainly due to a historical hiatus between child/adolescent and adultpsychiatry.However,theneedforalifespanperspec- tiveisbecomingincreasinglyapparent,andisenhancedby thevoicesofpatientsandtheirrepresentatives(seee.g.the Textboxbelow).Inthisreview,wepresentselectedlitera- ture tosummarisethecurrent knowledgeonADHDfroma developmental,lifespan perspective. Preventivemeasures aswellasage-specificdiagnosticsandinterventionsrequire knowledgeaboutthehighlydynamicchangesinADHDpre- sentation fromchildhoodtoadulthood, andour reviewof the current state of knowledgeis intended toprovide re- searchersandclinicianswithanoverviewonthetrajectory ofthisdisorder.Wefocusonphenotypicchangesacrossthe lifespan, ageofonsetissues(alsocoveringtherecentdis- cussiononadultonsetADHD),lifespanaspectsofcomorbid- ity, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, as well as aspects of disease outcome with and without treatment.Inaddition,wesummariseknowledgeoncogni- tiveandneuroimagingchangesduringlifewiththedisorder and touchonlifespan aspectsin thestudy of geneticand environmentalriskfactorsforthedisorderaswellasthein- terplayofthosetwo.Subsequenttothesereviews,wepoint outexistingknowledgegapsandidentifyneedsforfurther research.

Textbox. Thepatientperspective– contributedbyAndreaBil- bow,PresidentofADHD-EuropeandFounderandChiefExec- utiveoftheAttentionDeficitDisorderInformationandSupport Service(ADDISS)

Despiteconsiderableadvancesinourunderstandingof ADHD, patients still experience significant problems gainingaccesstothesupportandtreatmenttheyneed.

Service usergroupsareestablishedinmost European countries. One of these groups, ADHD-Europe (http:

//www.adhdeurope.eu), aims to advance the rights

of, and advocate on every level throughout Europe, forpeopleaffectedbyADHDandcomorbidconditions, helpingthemreachtheirfull potential.ADHD-Europe playsacriticalrolein promotingawareness ofADHD andevidence-basedtreatments,facilitatetheefforts ofnationalandregionalADHDsupportgroups,andad- vocatetoEuropeanInstitutionsforthedeliveryofap- propriateservicesforchildren,adolescents,andadults withADHD.

Currently, the experience of service users is that theyareoftendirectedtowards servicesthatdo not recognisethespecificproblemsrelatedtoADHD.This isaparticularproblemforadultswithADHD,although thequalityandavailabilityofchildservicesalsovaries considerably across different countries and regions.

Patients often feel there is nowhere to go for help withADHD-relatedproblems. Inmostcases,adultso- cialcare does not yet cater for ADHD. At the same time,old age,learning disability, and mental health teamsoftendonotconsiderADHDasamentalhealth problem,whichthenfallsbetweenthecracks,withno service provision available. The lack of supportcon- tributes topeople with ADHD experiencing more se- vereproblemswithage.Whenfacedwithchallenges, they may feel overwhelmed and develop or exacer- batecomorbid problems suchasanxiety,depression, anddruguse,whichthencomplicateADHD.Muchmore workaroundsocialcareandsupportisrequired.

Evenwheretherearehealth-careservicesforADHD, theapproachisoftentousedrugsalonewithoutpro- vidingthe additionalpsychosocialsupportthat is re- quired.Inmostcases,itisnotenoughtojustseesome- one and give a prescription. Health-care profession- alsneedtoconsidertheenvironmentalcircumstances ofeachindividual,andcliniciansneedtothink“what morecanIdofor thatperson”.Practicalsupportcan come in many ways, but the key is to have a single personcoordinatingthetreatmentpackage– onewho isawareofthe individualcircumstancesanddifficul- tiesfacedby peoplebeingtreated forADHDandcan providepracticalsupportasrequired.

Medicationisviewedasanessentialtooltoensure thatothersupportsbecomeeffective.However,medi- cationoftendoesnotfullycontrolallofthesymptoms ofADHD,andmostimportantly,does notbuildskills.

Organisationalskillscanimprovewithmedication– be- ingless distractedandmoreabletostay ontaskand getthingsdone– butpeoplestillneeddailylifeskills.

Forexample, someone may remain overwhelmed by tasks suchas howto tidy up a room,how or organ- iseandcomplete paperwork,andhowtoplanahead forthesuccessfulcompletionoftasksandideas.

Scaffolding and support for people with ADHD is complexandspecialised.Oneoftheproblemsisthat support is often offered for short periods, such as 3 months, but then they are on your own. Lifelong scaffolding and supportmay be required. To fillthe gap in service provision, a considerable amount of necessary practical and psychosocial support is cur- rentlyprovidedbythevoluntarysector.Oneapproach

advocatedbyADHD-Europeistoinvestinthevoluntary sectortoprovidethesupportservicesrequired,rather thanrelyongood-will ofpatientsupportgroups.This isparticularly importantasthe roleofthe voluntary sector is limited in whattheycan do due tolack of funding.

2. Phenotype of ADHD across the lifespan – course and changes in presentation over time

ADHD is defined asa persistent, trans-situational pattern ofinattentionand/orhyperactivity-impulsivitythatisinap- propriate to thedevelopmental stage andinterferes with functioningordevelopment(APA,2013).Importantly,ADHD symptomsassuchdonotreflectamanifestationofopposi- tionalbehaviour,defiance,hostility,orfailuretounderstand tasksorinstructions,althoughsuchproblemsareoftenseen toaccompanyADHD.Meta-analysisoflongitudinalfollow-up studiesofchildrenwithADHDsuggeststhatatleast15%con- tinuetomeetfulldiagnosticcriteriaforADHDbytheageof 25years,andafurther50%meetcriteriafor ADHDinpar- tial remission,withpersistenceof subthresholdsymptoms still causing impairment (Faraone et al., 2006). However, thereisconsiderable heterogeneity inthoseestimates, as e.g.morerecentestimatesofpersistenceintoyoungadult- hood for children and adolescentsdiagnosed withDSM-IV combinedtypeADHDinEuropearemuchhigher(upto80%) (Cheungetal.,2015a;vanLieshoutetal.,2016b),perhaps reflecting the severityof cases included in these studies, and/ortheuseofinformant-ratherthanself-ratings.

Prevalence rates for ADHD in children range around 6.5% (Polanczyk et al., 2007). Estimates for adults vary widelyacrossstudies,butaveragearound2.5–3.4%inmeta- analysis(Fayyad etal.,2007; Simonetal., 2009).Fayyad etal.(2017)citeestimatesrangingbetween1.4and3.6%.

Such variation is almost certainly due to methodological differencesin thewaythediagnosticcriteriaareapplied, including the childhood onset of symptoms, the methods to capture the 18 behavioural symptoms used to define the condition, and the application of impairment criteria (Willcutt,2012).Definitionsofimpairmentareaparticular issue,becauseADHDsymptomsareknowntobecontinually distributedthroughoutthepopulation,withnoclearsepara- tionbetweenthosewithandwithoutADHD(Mulliganetal., 2008). The disorder is therefore defined by high levelsof symptomswhentheyinterferewithorreducethequalityof social,academic,oroccupationalfunctioning(NICE,2013).

This might also at least in part underlie the discrepancy between cross-sectional, epidemiological studies showing adult ADHD prevalence rates almost as high as childhood prevalence rates (Fayyad et al., 2017), and longitudinal samples that suggest adult prevalence rates to be much lower(Faraoneetal.,2015).

Characteristic changes occur in the profile of ADHD symptoms throughout development. Very young children aremore likelytodisplay externalisingsymptomssuch as hyperactive-impulsivebehaviour,whileinmiddlechildhood inattentivesymptomsbecomemoreapparent,andbylate

adolescenceand in adulthood it is inattention that tends topersist, while thereis a decline in themore objective signsof (motor) hyperactivity (Francxet al.,2015b; Will- cuttetal.,2012). Emotionallability, however, becomesa growingburden,whichcanevendominatetheclinicalpic- ture. It is this changing profile and instability in the bal- anceofsymptomspresentingthroughoutdevelopmentthat ledtodisbandingoftheDSM-IVADHDsubtypesofpredom- inantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, andcombinedsubtypes;thosearenowreferredtoasclin- icalpresentationsinDSM-5. Althoughmanyadultspresent with predominantly inattentive symptoms, this is not to meantheyhavethesamerateofhyperactiveor impulsive symptomscomparedtoage-matched controls.Persistence of more overt hyperactivity-impulsivity is seen at higher rates especially among those with some of the most se- verecomorbidproblemsrelatedtoADHD,suchassubstance abuseandantisocialbehaviour(Huntleyetal.,2012).

Sexdifferencesin therates ofADHDareprominent but change throughoutdevelopmentin both clinicaland com- munitysettings (Kooijet al.,2010; Larsson etal., 2011).

Typically, in child and adolescent clinics, around 80% of ADHDcasesaremale,whereasinadultclinics,thepropor- tionofmalesiscloserto50%(Kooijetal.,2010).Onepossi- blereasonforthepredominanceofmalesinchildclinicsis thegreaterhyperactivity-impulsivitylevelstheyshowcom- paredtogirls,whoaremorelikelytodisplaypredominantly inattentivesymptomsandlessovertdisruptivebehaviours.

Severallinesofevidencesupportthisnotion.Forexample, anepidemiologicalsurveyofchildhoodADHDfoundthera- tio of male tofemale cases was 7.0 for the hyperactive- impulsivesubtype,4.9for thecombinedsubtype,and 3.0 for the inattentivesubtype of ADHD. However, therewas stilla greater percentageof boyswith ADHD of any sub- type (3.6%) compared to girls (0.85%). This is consistent withmean scores for ADHD symptoms in general popula- tionsamplesthat showthat,asa group,boyshave higher levelsofbothinattentiveandhyperactive-impulsivesymp- toms than girls. Interestingly, by late adolescence, while sexdifferencesininattention appeartoremain,thelevel ofhyperactivity-impulsivityinboysdeclinestothelevelof thegirls(Larssonetal.,2011),suggestingthattheexpres- sionofcoreADHDsymptomsismoresimilaracrossthesexes intheadultpopulation.Inadditiontosexdifferencesinthe expressionofcoreADHDsymptoms,itislikelythatcomor- bidproblemscontributetodifferentreferralratesforboys comparedtogirls,withboyspresentingwithmoreexternal- isingdisruptivebehavioursandlearningproblems.Inadults, itiswellknownthatwomenaremorelikelytoseekhelpfor mental health problems, impacting on referral rates, but levelsof comorbid disorders appear tobe similarin both menandwomenwithADHD(Biedermanetal.,2004).

Whilediagnostic criteria for ADHD originate from diag- nosis of children, the currently used diagnostic criteria, whenappliedtoadults,arealsowell-validatedandthere- fore appear to work well in the classification of clinical casesofthedisorder(Asherson etal.,2010).Validationof thediagnosticcriteriaalsorequiresthepredictionoffunc- tionalandclinicalimpairments(NICE,2018).Yet,mostclin- ical experts are aware of a broader expression of symp- toms commonly reported by adults with ADHD (Asherson et al., 2016; Kooij et al., 2010) falling into three main

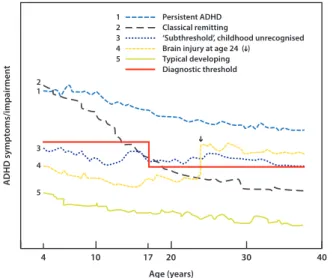

Fig.1 TheoreticaldevelopmentaltrajectoriesofADHDacross thelifespan.Detailsaregiveninthetext.

categories: age-adjusted expression of core ADHD symp- toms, behaviours reflecting problems with self-regulation (executive functions), and additional problems that are commonly seen in ADHD. Age-adjusted ADHD core symp- toms include some items in DSM-5 (APA, 2013) and e.g.

internal restlessness, ceaselessunfocused mental activity, and a difficulty focusing on conversations. Problems with self-regulationaree.g.problemswithcontrollingimpulses, switching attention,regulating emotionalresponses, initi- atingtasks,andproblem-solving.Interestingly,whilethese are strongly correlated with the core ADHD symptoms of inattention andhyperactivity-impulsivity,theydonotcor- relate strongly withneuropsychological testsof executive or top-down cortical control (Barkley, 2010; Barkley and Fischer, 2011),suggestingthat, likecoreADHD symptoms, they result from deficits across multiple neural networks and cognitive processes. The additionalproblems seen in many adults include sleep problems and low self-esteem (Kooijetal.,2010).Furthermore,astudythatcarefullyse- lected adult ADHDcases withnoevidencefor acomorbid disorder nevertheless found high rates of general mental healthsymptoms,suchassubthresholdanxietyanddepres- sion(SkirrowandAsherson,2013).

3. Age of onset and current discussion on adult onset of ADHD

As pointed outabove,ADHD hasalways been viewedasa childhood-onset condition, although the firstage at onset criterion wasnot seen until the advent of DSM-III, which requiredonsetpriortoage7years(APA,1980).Thisthresh- old was raised to age 12 years in DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Pa- tients,however,canmeetsymptomandimpairmentcrite- riaatlaterages.Sometimes,suchcasesareclearlydueto brain injuries (Fig.1).Ifso,theyareusually classifiedas

“secondary” or“acquired” ADHD,tobedistinguishedfrom the childhood onset of ADHD discussed above (Schachar et al., 2015).Longitudinal studies reporta two-fold rela- tive risk ofreceiving adiagnosis of ADHDafter mild trau-

maticbraininjury(TBI)(Adeyemoetal.,2014);moresevere braintraumacarriesanevenhigherriskforADHD(Schachar etal.,2015).Overall,15–50%ofchildrenwithTBIdevelop secondaryADHD(Schacharetal.,2015),whichmaybeclin- icallyindistinguishablefromidiopathicADHD.Becausepeo- plewith ADHDare atrisk for accidents (Dalsgaard etal., 2015b),ADHDmaybeariskfactorfor headinjuries(Fann etal., 2002), although thishas been difficult toestablish (Adeyemo et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it is possible that somepatients withADHD emergingsubsequenttoTBIhad undiagnosedADHDor subthresholdADHD priortotheirin- jury.

Incontrasttothewell-establishedlinkbetweenTBIand ADHDinadulthood,theideathatidiopathicADHDarises,de novo,inadulthoodiscontroversial.Threepopulationstud- ies estimated high rates of adult-onset idiopathic ADHD, with a prevalence of 2.7% in New Zealand (NZ) (Moffitt etal.,2015),10.3%inBrazil(Cayeetal.,2016),and5.5%in theUnitedKingdom(UK)(Agnew-Blaisetal.,2016).Theau- thorsconcludedthatADHDcanonsetinadulthoodandthat the adult-onset form of the disorder is categorically dis- tinctfromthechildhood-onsetform.Yettheseconclusions were premature. All threestudies hadsome seriouslimi- tations(FaraoneandBiederman,2016).Firstly,theageof theadultsinthestudiesfromBrazilandtheUKwasonly18 to19years,sothesestudiesprovidenoinformationabout mostoftheadultperiod.Secondly,inallthreestudies,the ratesofchildhood-onsetadultADHDweremuchlowerthan expected(Fayyadetal.,2017),suggestingthatmanyofthe childhood-onsetcasesmayhavebeen missedandmisdiag- nosedasadultonset.Thirdly,allthreestudiessufferfrom the“falsepositiveparadox”,whichisthemathematicalfact that,intheabsenceofperfectdiagnosticaccuracy,manyof thediagnosesinapopulationstudywillbefalsepositives.

Forexample,iftheprevalenceofadultADHDis5%,andthe falsepositiverateis only5%,then halfofthe adultADHD diagnosesinapopulationstudywillbefalsepositives.Con- sistent withthisidea, Sibleyetal. (2017) concluded that adultonsetofADHDisrare,andthatmostpeopleexceeding thesymptomthresholdfor diagnosisare,oncloserexami- nation,falsepositives.Afourthcaveatforthethreestudies isthatthedistinctionbetweenchildhoodonsetandadult- hoodonsetwasconfoundedbythemethodofdiagnosis:the formerdiagnoseswerebasedonparent-report,whereasthe latterwerebasedonself-report.Thisisaproblem,because anotherlongitudinalstudyfoundthatcurrentsymptomsof ADHDwereunder-reportedbyadultswhohadADHDinchild- hood andover-reportedby adultswhodidnothave ADHD in childhood (Sibleyet al., 2012). Moreover, considerable evidencesuggeststhat, comparedwithinformant-reports, self-reportsof ADHD inadults arelessreliable. The noise addedbyself-reportscanbeseenintheverylowheritabil- ityforadultADHD reportedbytheUK study(35%;Agnew- Blaisetal.,2016),whichcontrastswiththehigherheritabil- ityofadultADHDfromparentreportorusingdiagnosticcri- teria(Brikelletal.,2015).

Inallthreestudies,aparticipantwasdefinedashaving

“adult-onset” ADHDonlyiffulldiagnosticcriteriaforADHD hadnotbeenachievedatpriorassessments.Ineachstudy, however,manyofthe“adult-onset” cases hadevidenceof psychopathologyinchildhood.IntheNZstudy,intheirchild- hoodyears,theadult-onsetADHDgrouphadmoreteacher-

ratedsymptomsofADHD,weremorelikelytohavebeendi- agnosedwithconductdisorder(CD),andweremorelikelyto havehadacombinedparent-teacherreportofADHDsymp- tom onset prior toage 12 years(Moffitt et al., 2015). In the UK study,the adult-onsetcases had significantly ele- vatedratesofADHDsymptoms,CD,andoppositionaldefiant disorder (ODD) in childhood(Agnew-Blais etal.,2016).In thestudyfromBrazil,onlyaboutathirdoftheadult-onset caseswerefreeofADHDandCDsymptomatologyinchild- hood (Caye etal.,2016). These populationstudies mirror retrospective reports fromreferred cases, in which many lateadolescent and adult onsetcases ofADHD had child- hoodhistoriesofpsychopathology(Chandraetal.,2016).

Faraone andBiederman (2016) suggestedthat apparent casesofadult-onsetADHDaremostlyduetotheexistence of subthresholdchildhoodADHD. Forexample, aprospec- tivepopulationstudydefined“subthresholdADHD” (Fig.1) ashavingthreeor moreinattentivesymptomsor threeor morehyperactive-impulsive symptoms(Lecendreuxetal., 2015).Itfoundthatnew-onsetcasesofADHDinadolescence were significantly more likely to have had subthreshold ADHDatbaseline.Insubthresholdcases,theonsetofsymp- toms and impairment could beseparated by many years, particularlyamongthosewithsupportiveinternalresources (e.g.,highintelligence)orsupportivesocialenvironments.

Given the issues discussed above, and until more evi- dence is available, it seems best to refer to the adult- onset cases reported by the studies from NZ, Brazil, and the UK as apparent adult-onset ADHD (AAOA). An urgent clinical question iswhether stimulanttreatment is appro- priateforAAOA.Thisissuehasnotyetbeensystematically assessed. Fromaclinical perspective, AAOAcasesrequire extra caution. Although many show significant functional impairments thatrequiretreatmentsforADHD, somemay haveotherdisorders.

Inconclusion,substantialresearchindicatesthatadiag- nosableADHDsyndromecanariseinadulthoodsubsequent tobraininjury.Other formsofapparentadult-onsetADHD mayexist,butmanyofthesearelikelytohavehadundiag- nosedADHDorsubthresholdADHDinyouth.

4. Comorbidity profile changes over time

To complicate matters further, not only does the clinical phenotype of ADHD change over the lifespan, but comor- bidconditionsmight dominatethe initialappearanceof a patient. This is of high relevance as ADHD patients fre- quentlysufferfrompsychiatricandnon-psychiatriccomor- bidconditions,posingsignificantclinicalandpublichealth problems (Angold et al., 1999). Throughout the lifespan, thespecificpatternof comorbiditieschangessubstantially (Costelloetal.,2003;Taurinesetal.,2010):inshort,while inchildrenoppositionaldefiantdisorder(ODD)andconduct disorder(CD)arethemostprevalentcomorbidconditions, substanceusedisorders(SUDs)becomemoreandmoreofa problemduringadolescenceandevenmoresoinadulthood.

The comorbidity pattern of adult ADHD is highly diverse, andinadditiontoSUDsencompassesmoodandanxietydis- orders, antisocial personality disorder (ASP), sleep disor- ders(Jacobetal.,2007),aswellasmanysomaticdiseases (Instanesetal.,2016).The developmentaltrajectory,risk

factors,andmoderatorsofthislifelongcomorbiditycourse, however,arecurrentlyonlypoorlyunderstoodandrequire futurelongitudinalstudies.Below,informationonthemost prominentADHDcomorbiditiesisgiven.

4.1. Autismspectrumdisorders,tics,and learningdisorders

ADHDand symptomsof autisticspectrumdisorders (ASDs) oftenco-exist,as20–50%ofchildrenwithADHDalsomeet criteriafor ASDs (Rommelseet al.,2011). Several studies have shown social deficits, peer relationship, and empa- thyproblemstobecommoninADHD,andaccordingly,the DSM-5finallyallowsacomorbiddiagnosisofADHDandASD.

TheADHD-ASDcomorbidityhasmainlybeenstudiedinchil- dren;areviewandmeta-analysis,however,supportitsex- istencealsoin adults(Hartmanetal.,2016).Recent data fromalarge,register-basedstudyfromSwedensuggestthat thecomorbidityhasitsrootsinsharedgenetic/familialfac- tors (Ghirardi et al., 2017). Tic disorders occur in up to 3–4% of the population (Robertson et al., 2009; Roessner et al., 2011) and are seen in 10 to 20% of children with ADHD(Cohenetal.,2013;Steinhausenetal.,2006).Over the course of years, tic severitytypically peaks between 8 and12 years of age. The natural history of tics usually showsamarkeddeclineduringadolescence(Cohenetal., 2013).Populationstudies suggestthat intellectual disabil- itymaybemorecommon(upto5–10times)in ADHDthan inchildrenwithoutADHD(Simonoff etal.,2007).About25–

40%ofallpatientswithADHDhavemajorreadingandwrit- ingdifficulties,andmany showco-existing languagedisor- ders(Sciberrasetal.,2014;Willcuttetal.,2012).Similarly, thereis a considerable overlapbetween ADHD anddisor- dersofarithmeticalskills(Hartetal.,2010;Rapportetal., 1999).AsforASD,hardlyanyinformationisyetavailableon thelifespantrajectoriesofADHDwithsuchcomorbidities.

4.2. Rule-breakingbehaviours

The comorbidity of ADHD withantisocial behaviours is of particularsocietalrelevance,asADHDseemstoconveyan increasedrisk for violence andincarceration especiallyin the context of such comorbidity (Rosler et al., 2004). In childrenandadolescents,bothclinicalandepidemiological studiesshowahighprevalenceofcomorbidityofADHDwith ODD/CD, ranging from 25% up to 80% (median odds ratio (OR):10) indifferentstudies.ODDandCDpredict amore severeclinicalsymptomatology,moreseverefunctionalim- pairments,higherpersistenceofADHDintoadulthood,and worseoutcomeofthedisorder.Theyalsomediatetherisk forthedevelopmentof otherproblems,suchassubstance useanddepression(Burkeetal.,2002;Hill,2002).Comor- bid ODD in childhood seems to also increase the risk for CD/ASP and depression in ADHD later in life, and comor- bidCDdoesevenmore(Biedermanetal.,2008;Mannuzza et al., 2004). Increased impulsivity may be an important riskfactor within theADHD group forthese negativeout- comes(RetzandRosler,2009;StoreboandSimonsen,2016).

However,ADHD-affectedchildrenwithoutthesecomorbidi- ties may also develop antisocial behaviours later in life

(Jensenetal.,1997;Loeberetal.,1995;Mannuzzaetal., 2004).SUDs andenvironmental variables might be impor- tantmoderatorsinthis,althoughthishasyettobeformally established.

4.3. Substanceusedisorders

Another (related)issue of importance in ADHD acrossthe lifespan is the liability todevelop addictions.The earlier onsetandincreaseduseoftobacco,alcohol,andillicitsub- stancesinadolescentswithADHDcomparedtocontrolshas been demonstrated in various studies, and a high preva- lenceofdrugabuseordependency(9–40%)isalsoreported in adulthood (Buchmannet al., 2009; Jacobet al.,2007;

Mannuzza et al., 1993; Milberger et al., 1997). A meta- analysis of cohort studies confirmed that childhoodADHD significantly increases the risk for nicotine use in middle adolescence(OR:2.36, 1.71–3.27)andtheriskfor alcohol use disorder during young adulthood (OR: 1.35, CI: 1.11–

1.64) (Charach et al.,2011). This meta-analysisalso sug- gestedthatchildrenwithADHDmayhave anelevatedrisk for cannabis useandpsychoactivesubstance useasyoung adults,butsignificantheterogeneityexistsbetweenstudies, andtheassociationwithdrugusedisorderwashighlyinflu- encedbyasinglestudy.As anothermeta-analysisshowed, controllingforcomorbiddisorders(particularlyCD)substan- tially weakenedthe association between ADHD and SUDs;

infact,itcouldnotbeconfirmedthatADHDincreasesthe riskforSUDsbeyondtheeffectsofCD/ODD(Serra-Pinheiro et al.,2013). Lookedat fromtheother side, inadult pa- tients suffering fromalcohol abuse,30–70% suffered from childhoodADHD,and15–25%stilldisplayedthedisorderas adults.

4.4. Moodandanxietydisorders

AdultADHDissignificantlycomorbidwithanxietydisorders (upto25%;medianOR:3.0)andmajordepression(5–20%;

median OR: 5.5).Although thesedisordersareamongthe mostcommoncomorbiditiesofADHD,especiallyinadoles- cents(Meinzeretal.,2013)andadults(Jacobetal.,2007), surprisinglylittleisknownaboutthedevelopmentaltrajec- tories of such comorbidity. As mentioned above, ODD/CD seem to be associated withlater-life affective disorders;

also,depressiveandanxioussymptomsduringchildhoodand adolescencegoalong withincreasedriskforadult-life de- pression(asdogeneralriskfactorsfordepression),although oftennosuchantecedentscanbefoundinadultADHDwith depression. Rather, childhood ADHD itself seems to be a risk factorfor thelaterdevelopmentofdepression,which canbereducedbye.g.methylphenidatetreatment(Chang etal.,2016).

4.5. Disruptivemooddysregulationdisorderand bipolardisorder

An issueofincreasinginterestinresearchandclinicis the presenceofextremeanduncontrolledemotionalandmood changesinbothchildrenandadultswithADHD.Indeed,in

DSM-5,problemswithemotionregulationarelistedaschar- acteristicfeaturesofADHDthatsupportthediagnosis.Emo- tionaldysregulationandADHDareknowntosharegenetic risks(Merwoodetal.,2014).InadultADHD,emotionaldys- regulationoccursalsointheabsenceofcomorbiddisorders (SkirrowandAsherson,2013),isanindependentpredictor ofimpairment(BarkleyandFischer,2010;SkirrowandAsh- erson,2013),andrespondstobothstimulantsandatomox- etine(Moukhtarian etal.,2017).Insome cases,specialist referral is advised to ensure accurate diagnosis, because the problems may be complex and predictive of particu- laradverseoutcomes(Sobanskietal.,2010;Stringarisand Goodman,2009).Comorbiditywithbipolardisorderandbor- derlinepersonalitydisorder bothneedtobeconsideredin adults,sinceADHDmayco-existwiththeseconditions,but mayalsomimicthem inthepresenceofsevere emotional dysregulation (Asherson etal.,2016).Cross-sectional epi- demiological studies as well asfamily-based studies show thatthereisincreasedcomorbiditybetweenbipolardisor- derandcurrentorlifetimeADHD;mutualcomorbidityrates are around 20% (Kessler et al., 2006). The developmen- tal trajectories of this comorbidity are unclear, however, sincebipolardisorderisrareinpre-adolescents,evenwhen severe irritability and anger are prominent in this group (Brotman etal.,2006).The newDSM-5 diagnosis “disrup- tivemooddysregulationdisorder(DMDD)” forchildrenupto age8yearsexhibitingpersistentirritability,intoleranceto frustration,andfrequent episodesofextremebehavioural dyscontrolcapturesthosesymptoms,yetthecourseofthis syndromeintofull-blownbipolardisorderisfarfromestab- lished. Importantly,most of the DMDD patients alsomeet criteriaforADHD.

5. Treatment and response to treatment over time – pharmacological and

non-pharmacological treatments

ThecontinuityoftreatmentofADHDacrossthelifespanis anissuethatstillreceivestoolittleattention.Especiallythe transitionfromadolescencetoadulthood,whichisaccom- paniedbyatransitionfromchildandadolescentpsychiatric clinicstoadultpsychiatry,isproblematic;manypatientsare losttofollowupatthatpoint.Ateveryage,recommended treatmentofADHDshouldbemultimodal,includingpsycho- education, pharmacotherapy, and disorder-oriented psy- chotherapy,includingtraining,cognitive-behavioural ther- apy,andfamilyorcoupletherapyifneeded(Faraoneetal., 2015;Kooijetal.,2010;NICE,2018).

PharmacologicaltreatmentswiththeindicationforADHD are traditionally divided into two groups: stimulants and non-stimulants. Methylphenidate and amphetamines are the stimulant options, and atomoxetine, guanfacine, and clonidinearethenon-stimulants(Faraoneetal.,2015).The same drugs are used across the lifespan in clinical prac- tice,butonlymethylphenidate,lisdexamfetamine,andato- moxetine are officially approved for treatment of ADHD in childhood and adulthood in most European countries (Ramos-Quiroga et al., 2013). Unsurprisingly, there have been manymoreclinicaltrialsevaluatingtheefficacyand safety of these drugs in children than in adults (Faraone

Table1 Reportedeffectsizes(standardisedmeandifference)frommeta-analysisforstudiesoftreatmentefficacyforADHD coresymptomsinchildhoodandadulthood.

Treatmentandage-group Treatmenttype Effectsize Reference

Childhood:pharmacological treatment

Methylphenidate 0.72 FaraoneandBuitelaar(2010)

Amphetamines 0.99 FaraoneandBuitelaar(2010)

Atomoxetine 0.64 SchwartzandCorrell(2014)

Guanfacine 0.63 Hirotaetal.(2014)

Clonidine 0.44 Hirotaetal.(2014)

Childhood:non-pharmacological treatment

Omega-3 0.16 Sonuga-Barkeetal.(2013)

Diets 0.42 Sonuga-Barkeetal.(2013)

Neurofeedback 0.21 Hodgsonetal.(2014)

Multimodalpsychosocial 0.09 Hodgsonetal.(2014)

Workingmemorytraining −0.02−0.20 Corteseetal.(2015);Hodgson etal.(2014)

Behaviourmodification −0.03 Hodgsonetal.(2014)

Parenttraining −0.51 Hodgsonetal.(2014)

Self-monitoring −5.91 Hodgsonetal.(2014)

School-based −0.26−0.16 Hodgsonetal.(2014);Richardson etal.(2015)

Adulthood:pharmacological treatment

Methylphenidate 0.42−0.72 Castellsetal.(2011b;Epstein etal.(2014

Amphetamines 0.72−1.07 Castellsetal.(2011a);Fridman etal.(2015)

Atomoxetine 0.38−0.60 Ashersonetal.(2014);Fridman etal.(2015)

Adulthood:non-pharmacological treatment

Cognitive-behaviouraltherapy 0.43−1.0 Jensenetal.(2016);Knouseetal.

(2017);Youngetal.(2016) Mindfulness-basedtherapies 0.53−0.66 CairncrossandMiller(2016)

and Buitelaar, 2010; Fridman et al., 2015). Nevertheless, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trials and meta- analysesconvincinglyshowtheeffectivenessandsafetyof both stimulant and non-stimulant drugs for ADHD also in adults(Epsteinetal.,2014;Fridmanetal.,2015)(Table1).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend pharmacotherapy as first- line treatment for adult ADHD (NICE, 2018) and consider methylphenidate asthe first choice for the treatment of adults, based on available meta-analytical evidence. Ap- parent differencesin the effect sizefor methylphenidate across the lifespan arelikelydue to differentdosing reg- imens appliedin the clinical trials.Doses around1mg/kg ofmethylphenidatearecorrelatedwithbetterefficacy,yet are rarely achieved in studies of adult patients. Regard- ingamphetaminesoratomoxetine,thesituationissimilar;

highest doses arerelated withbestefficacy. Anotherfac- tor that may explain the discrepancies in effect sizes is thepresence ofcomorbid disorders.As anexample, stud- iesthat included patients with SUDshave shown compar- ativelysmaller effectsizes. The influenceof such comor- biditiesontreatment outcomeis notexclusivelyobserved in pharmacological trials, the same is seen for studies of non-pharmacologicaltreatments.

In termsofdrug treatment sideeffects, themost typi- calaredecreasedappetite,sleepdisturbance,headaches, drowsiness,tearfulness,abdominaldiscomfort,nauseaand vomiting,irritability,moodchanges,constipation,fatigue,

sedation, and increasedblood pressure andpulse. Delays inheightandweightarerelatively minorwithstimulants, oftenappeartoattenuatewithtime,andseemnottoaf- fect ultimate height and weight in adulthood (Fredriksen etal., 2013).Thecardiovascular safetyof stimulantmed- icationsandatomoxetinehasbeenasubjectofdebateover manyyears.Itisquitesurprisingthatthiscontroversyoccurs fordrugssuchasmethylphenidate,whichhavebeenonthe marketforover50years.Cohortstudies,however,didnot findanincrease inseriouscardiovascular eventsfollowing ADHDmedicationsinchildrenoradults,althoughbothstim- ulants andatomoxetinewere found associatedwithslight increasesinheart rateandblood pressure(Cooperetal., 2011).

Public concerns that stimulant treatment in childhood andadolescencemayincreaseSUDsinadulthoodseemun- substantiated.Acomprehensivemeta-analysisoflong-term studies indicates comparable outcomes between children withandwithoutmedicationtreatmenthistoryforanysub- stanceuseandabuseordependenceoutcomeacrossallsub- stancetypes(Hamshereetal.,2013);accordingly,Scandina- vianregistrystudies(Changetal.,2014b;Dalsgaardetal., 2014)foundthatADHDmedicationwasnotassociatedwith increasedrateofsubstanceabuse;ifanything,thedatasug- gested a long-term protective effect on substance abuse (Changetal.,2014b)(seebelow).

ResearchofpharmacotherapyinadultswithADHDisstill largely lacking, especially with respect to clinical trials

comparing different treatments (pharmacological or psy- chological) head to head as done in a pioneering study (Philipsenetal.,2015).Atthesametime,itisnecessaryto improvetheexternalvalidityofthesestudies.Mostofthe existingclinical trialsin thisareaaretheones performed toreachindication foradultsfor a particulardrug.These studies usedveryrestrictiveinclusion andexclusioncrite- ria, rarely reflecting real-life patients. A second area, in which more researchis needed, is the systematic assess- ment oftheefficacy andsafetyofADHD treatmentin the presence of comorbid disorders, especially psychosis. Fi- nally,itisknownthataround30%ofADHDpatientsdonot respondtocurrentlyavailabletreatments(Faraone etal., 2015).Itisthereforeimportanttoinvestigatenewpharma- cologicaltargetsbeyondthedopaminergicandnoradrener- gicsystems,preferablyincludingnewknowledgeonthebi- ologicalpathwaysinvolved inADHDaetiology(see below).

Onelineofevidencecomesfromatrialoflowdosecannabi- noids,whichfoundmoderatetolargeeffectsoncoreADHD symptomsintheabsenceofadverseeffects;thisstudyim- plicates thecannabinoidsystemasapotential newtarget fordrugdevelopment(Cooperetal.,2017).

It isimportanttohighlight thepositiveimpactofADHD treatment onaspectsofdailyfunctioning.Althoughinitial studies were disappointing regarding the longer-term ef- fects oftreatment (Molina etal.,2009), thestudies from Scandinavianregistriesimpressivelydocumentpositiveout- comesoftreatment,asdiscussedbelow.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, several non- pharmacological approaches are used in the control and managementofADHDacrossthelifespan(Table1).Inmany countries, for children and adolescents with mild ADHD, non-pharmacological interventions arethefirst-line treat- ment.Inmoderateorseverecases,therecommendationis tocombinenon-pharmacologicaltreatmentanddrugtreat- ment(Faraoneetal.,2015).Thusfar,non-pharmacological treatmentsinchildhoodhavedemonstratedlesserefficacy inreducingADHDcoresymptomsthanADHDdrugs(Sonuga- Barke etal., 2013), but may have important benefits for co-occurring comorbidities and behavioural problems. In fact, only free fatty acid supplementation and exclusion of artificial food colour from the diet demonstrated sig- nificant beneficialeffects onADHD core symptomsduring childhoodinarigorousmeta-analysis,althoughtheeffects were relatively small (Chronis et al., 2006; Nutt et al., 2007; Philipsen, 2012; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2013; Young etal.,2015).Althoughcognitive-behaviouraltherapy(CBT) approaches have not been proven efficacious in children (Sonuga-Barkeetal.,2013),thefirststudieshavereported that individual CBT (Antshel et al., 2014) and group CBT (Vidal et al., 2015) could be effective treatments for adolescentswithADHD.

Of particular importance is the transition from child- hoodtoadultservices,requiringcontinuationofbothmed- ical and psychological support (Nutt et al., 2007). As in- dicated above, for adults, pharmacological treatment is therecommendedfirstchoice.GroupCBThasbeenproven to benefit adults with ADHD (Solanto et al., 2010), but one study showed that highly structured group interven- tion did not outperform individual clinical management with unstructured support with regard to the core ADHD symptoms (Philipsen etal., 2015). Promising findings also

raise thepossibilityof mindfulness-based interventions as aneffectivetreatmentforADHDsymptoms(Cairncrossand Miller,2016;Heparketal.,2015).Forother typesofnon- pharmacologicaltreatments,suchasneurofeedback,more evidence for efficacy from randomisedclinical trialswith blinded assessment is necessary for both adolescentsand adults(Corteseetal.,2016).

6. Disease outcome with and without treatment

Assessment of disease outcome in ADHD requires longitu- dinal study designs,which are generally scarce. As a re- sult,alsotheknowledgeabouttheroleoftreatmentduring thedifferentphasesoflifeinsuchoutcomesisstillpatchy.

Someclinically-basedstudiesofhighqualitythathavefol- loweduppre-adolescentswithADHDintoadulthoodareal- readyavailableandhavebeeninstrumentalindocumenting thediseaseoutcomesofADHDindifferentaspectsoflife.

Those include academic, occupational, andsocial aspects aswell asmorbidityandmortality.Ithasbeen shownthat ADHDis associatedwithacademic outcomes,suchaspoor academicperformance(e.g.,lowergradepointaverageand increasedratesofgraderetention)(Galeraetal.,2009)and lower rates of high-school graduation and post-secondary education (Galera et al., 2009; Klein et al., 2012; Man- nuzzaetal.,1993).ADHDisalsoassociatedwithnegative occupationaloutcomessuchasunemployment(Biederman et al., 2006; Klein et al., 2012), having trouble keeping jobs(Barkleyetal.,2006; Biedermanetal.,2006),finan- cial problems (Barkley et al., 2006; Klein et al., 2012), andworkincapacityintermsofsicknessabsence(Kleinman etal.,2009; Secniketal.,2005).Thosestudies havealso shownthatindividualswithADHDareat increasedrisk for poorsocial outcomessuchashighrates of separationand divorce (Biederman etal., 2006;Klein etal., 2012),resi- dentialmoves(Barkleyetal.,2006),andearlyparenthood (Barkleyetal.,2006).

In terms of mortality, several studies fromScandinavia have exploredtheassociation ofADHDwithmortalityand whichfactors arelikelytoincrease mortality.Thesestud- ieshave usedinformationfrom national registersin Swe- den and Denmark that have been linked using a unique person identifier.A Danish register-based study has found thatADHDisassociatedwithsignificantlyincreasedmortal- ityrates, andthattheexcess mortalityinADHD ismainly driven by deaths from unnatural causes, especially acci- dents(Dalsgaardetal.,2015b).Otherregister-basedstud- ies have confirmed that individuals with ADHD are at in- creasedrisk for serioustransportaccidents (Changetal., 2014a), and also show increases in criminality (Dalsgaard et al., 2013; Lichtenstein et al., 2012) and suicidal be- haviour(Ljungetal.,2014),whichareseverenegativeout- comes in their ownright and could contribute to the in- creasedmortality.

Systematicreviewsofthelong-termdiseaseoutcomesof treatedversusuntreatedADHDaresomewhatinconsistent.

This is partlybecauselong-term observational studiesare oftenlimitedbyalackofdataabouttreatmentcompliance and can be confounded by indication, since more severe caseswillbemorelikelytobetreated.Asystematicreview

of randomisedcontrolled trial open-label extension stud- iesandnaturalisticstudiesofadultswithADHD concluded that ADHD medications have long-term beneficial effects andarewelltolerated, butthatmorelongitudinal studies of longduration need tobeperformed (Fredriksenetal., 2013). A second systematic review of both childhoodand adultstudiesfoundthatADHDindividualsleftuntreatedhad poorer long-term outcomes compared to treated individ- ualsin severalmajorcategories includingacademic, anti- socialbehaviour,driving,non-medicinaldruguse/addictive behaviour, obesity,occupation, services use, self-esteem, and socialfunction outcomes,but that treatment didnot resultin normalisation (Shaw etal.,2012).In contrast,a thirdsystematic reviewofplacebo-controlleddiscontinua- tionstudiesandprospectivelong-termobservationalstud- iesconcluded thatADHD medication reducedADHDsymp- tomsand impairments,butthattherewaslimitedandin- consistentevidenceforlong-termmedicationeffectsonim- provedsocialfunctioning,academicachievement,employ- mentstatus,andpsychiatriccomorbidity(vandeLoo-Neus etal.,2011).Long-termplacebocontrolledtrialswouldbe neededtoallowdefiniteconclusions,yetthosearealmost impossibletoconductinreallife.

Pharmaco-epidemiological analyses of large-scale databases, such as the national registers in Scandinavia, are an alternative source of information about potential (long-term) effects of ADHD medication on important disease outcomes. A large register-based Swedish study of adults with ADHD found that treatment with ADHD medication significantly reduces the risk for criminality (Lichtensteinetal.,2012).AnotherSwedishregister-based studyfoundthatadultmaleswithADHDhada58%reduced risk of serioustraffic accidentsin periodsreceiving treat- ment, compared with periods without treatment (Chang etal.,2014a).This wasconfirmedinarecentstudybased on individuals with ADHD from a large insurance claims database, which found similarresults in a US setting and also among females (Chang et al., 2017). Three addi- tional pharmaco-epidemiological studies in children and adolescents, using data from a Danish record linkage of national registers (Dalsgaard et al., 2015a), a Hong Kong electronicmedicalrecordsdatabase(Manetal.,2015),and a German insurance database (Mikolajczyk et al., 2015), have further extended suchfindings to these age groups.

ADanishregister-based studyshowedthattreatment with ADHDmedicationreducedtheriskforinjuriesbyupto43%

and emergency ward visits by up to 45% in children with ADHD(Dalsgaardetal.,2015a).

Thepharmaco-epidemiologicalstudiescanalsohelpclar- ify the potential roleof medication in causing morbidity.

Forexample,tworegister-basedstudiesofadolescentsand adultswithADHDsuggest thattheco-occurrenceof ADHD and suicidal behaviour is due to shared familial risk fac- tors (Ljung et al., 2014), rather than to harmful effects of ADHD medications (Chen etal., 2014). A recent study in a self-controlled case seriesalso suggests that theob- served elevation of suicide attempt risk after medication initiation is not causally related to the effects of stimu- lants (Man et al., 2017). In this study, the incidence of suicideattempt washigherinthe periodimmediatelybe- fore the start of stimulant treatment. The risk remained elevated immediately after the start of stimulant treat-

mentandreturnedtobaselinelevelsduringcontinuationof stimulant treatment. Furthermore, the apparent increase inSUDriskinpatientstreatedwithstimulants,asdiscussed above,seemstobeduetofamilialityratherthanmedica- tioneffects. The previous concerns that stimulants could leadtoanincreasein SUDscouldnotbeconfirmedbythe pharmaco-epidemiologicalstudies;thesestudiesrathersug- gest a reduction in SUDs following medical treatment of ADHD(Changetal.,2014b;Skoglundetal.,2015).Another register-basedstudyfromSwedensuggeststhatADHDmed- icationdoesnotincreasetheriskoflaterdepression;alsoin thiscase,medicationwasassociatedwithareducedriskfor subsequentandconcurrentdepression(Changetal.,2016).

7. Changes in cognitive and neuroimaging profiles across the lifespan

Inadditiontoalifespanperspectiveonphenotypicandout- comeparametersinADHD,alsothedynamicsacrosslifein biological markers and risk factors for the disorder need tobe understood better. ADHD is associated with several cognitiveimpairmentsandbrainalterations,bothinchild- hoodandin adulthood.Cognitive deficitsin ADHDencom- pass both higher-level,effortful cognitive functions (e.g., inhibitory control, visuo-spatialand verbal working mem- ory,sustainedattention)andlower-level,potentiallymore automaticcognitiveprocesses(e.g.,temporalinformation processingand timing, vigilance, intra-individual variabil- ity,rewardprocessing)(Karalunasetal.,2014;vanLieshout etal.,2013;Willcuttetal.,2005).Meta-analysesofcogni- tivestudiesinchildrenestablishADHDtobeassociatedwith poorer performance on tasks measuring inhibition, work- ingmemory,planning,andvigilance(Huang-Pollocketal., 2012;Willcutt etal., 2005).ADHD is also associatedwith lowerIQscores(Frazieretal.,2004).Inaddition,morere- centstudies,includingmeta-analyses,indicateastrongas- sociationofADHDwithreactiontimevariability(RTV),cap- turinglapsesinattention(Frazier-Woodetal.,2012;Karalu- nasetal.,2014;Kuntsietal.,2010).Studiesofadultswith ADHD reveal overall similar patterns of cognitive impair- mentsasfound inchildrenandadolescents(Coghilletal., 2014;Frazier-Woodetal.,2012;Herveyetal.,2004;Kuntsi etal.,2010; Mostertetal.,2015;Mowinckeletal.,2015;

Sonuga-Barkeetal.,2010).

Structuralandfunctionalneuroimagingstudieshavedoc- umented abnormalities in brain anatomy and function in individuals with ADHD (Cortese et al., 2012; Frodl and Skokauskas, 2012; Greven etal., 2015). Meta-analyses of magneticresonanceimaging(MRI)studiesshowsmallervol- umesintheADHDbrain,mostconsistentlyinthebasalgan- glia(Frodl and Skokauskas, 2012; Hoogmanet al., 2017).

Thisis importantconsideringthe keyroleof basalganglia incognitivedeficitstypicallyobservedinADHD,likereward processing.Inparticular,smallerglobuspallidus,putamen, caudate nucleus, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and hip- pocampus,butalsosmallertotalintracranialvolume,were found in children withADHD, while in adults with ADHD, the subcortical volume reductions were less pronounced (Hoogman et al., 2017). A smaller anterior cingulate

cortex volume had been found earlier (Frodl and Skokauskas, 2012). One relatively large study further re- portedreductions intotalbrainandtotalgreymatter vol- umeinchildren,adolescents,andadultswithADHD,butno alterations in whitematter volumes (Greven etal.,2015) (but alsosee Onnink et al., 2015). Functional abnormali- ties are documented by a meta-analysis of 55 task-based functionalMRI(fMRI)studies(Corteseetal.,2012),report- ing that childrenwithADHD show ahypoactivation inthe fronto-parietal and ventral attentional networks involved in executive function and attention, and a hyperactiva- tioninthesensorimotornetworkanddefault-modenetwork (DMN), involved in lower-level cognitive processes. Adult ADHD is, instead,mostlyassociatedwithahypoactivation in thefronto-parietalsystem andahyperactivation inthe visualnetwork,dorsalattentionnetwork,andDMN(Cortese et al., 2012). Atypicalbrain activity has further been re- ported using EEG. For example, children and adults with ADHDshowalterationsinevent-relatedpotential(ERP)ac- tivityofattentionalallocation,inhibition,preparationand error processing during cognitive tasks (Albrecht et al., 2013; Cheung etal., 2016; Geburek et al.,2013), andin quantitativeEEGfrequencypower,mostlyincreasedpower of low frequency activity, during resting state (Kitsune etal.,2015).

Overall, cross-sectional studiesindicate thatmany cog- nitiveandbrainabnormalitiesareassociatedwithADHDin both children and adults,although some differenceshave alsobeenobservedbetweenagegroups.Lookingatthede- velopmentaltrajectoriesofcognitive,neuroanatomicaland neurofunctionalalterationsinADHD acrossthelifespan,it is important to examine whether cognitive and brain ab- normalities (1)showan age-independent,consistentasso- ciation with ADHD across the lifespan; (2) are predictors in childhoodoflater ADHDoutcome; (3)candifferentiate between individuals with persistent ADHD (from here on

“ADHDpersisters”)andindividualswhohaveremittedfrom ADHDovertime(fromhereon“ADHDremitters”).

Asforpoint(1),prospectivelongitudinalstudieswithre- peated assessments of ADHD and cognitive measures are neededtoconfirmcross-sectionalstudiessuggestiveofsim- ilar impairmentsacrossthelifespan.Suchstudiestodate, mostly focusing on higher-level cognitive functions using IQtests,executivefunctioningandattentionaltasks,show thatimpairmentstendtopersistfromchildhoodtoadoles- cence and early adulthood in ADHDpersisters (Biederman et al., 2009; Cheung et al., 2016; Hinshaw et al., 2007;

McAuleyetal.,2014).Fewerprospectivelongitudinalstud- ies have investigated the developmental association be- tween ADHD and lower-level cognitive impairments, such asintra-individualvariabilitymeasuredwithRTV.Thethree largeststudiesconductedtodateonRTV,usingmotortim- ing and attentional paradigms, indicate persisting impair- ments bothfrommiddle tolatechildhood(Vaughn etal., 2011)andfromchildhoodtoadolescence/earlyadulthoodin ADHDpersisters(Cheungetal.,2016;Thissenetal.,2014).

However,inoneofthesestudies theRTVimpairmentdur- ingamotortimingtaskdidnotpersistintheoldestgroupof adultsinvestigated,aged22yearsandabove(Thissenetal., 2014).Otherlongitudinalstudieshaveusedsmallersamples (Doehnert etal.,2010;Doehnert etal.,2013),notdistin- guishedbetweenpersistersandremitters(Doehnertetal.,

2013;Moffittetal.,2015),oruseddifferentcontrolgroups inchildhoodandatfollowup(McAuleyetal.,2014),making comparabilitytotheabovefindingsless clear.Thesestud- iesshowedthatdeficitsinvisual processing,vigilance, in- hibition, andIQmaycontinue in adultage (Moffittetal., 2015),whilecontinuityofRTVimpairmentswereobserved fromchildhood toadulthood (Doehnert etal., 2013), but notinadolescence(Doehnertetal.,2010;McAuley etal., 2014).

Among neuroimaging studies, longitudinal studies us- ingmultiple assessmentsfromchildhoodtoadulthood are scarce,andhavemainlyexaminedneuroanatomicalabnor- malities withMRI.Available MRI studies consistentlyshow that smaller brain volumes and morphometric abnormal- ities persist over time in ADHD persisters re-assessed in adolescenceandearlyadulthood(Castellanosetal.,2002;

Shaw et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2013). For example, de- velopmental abnormalities in cortical thinning have been observed inthe medialand dorsolateralprefrontalcortex (components of networks supporting attention, cognitive control,andtheDMN),whichresultedinapatternofnon- progressive deficit in persistent ADHD from childhood to youngadulthood (Shawetal.,2013).Corticalthinninghas also been found in ADHD in the medialand superior pre- frontalandprecentralregions,especiallyforADHDindividu- alswithworseclinicaloutcome:theADHDgroupfolloweda similardevelopmentaltrajectorytocontrolindividualsfrom initialassessmentsinchildhoodtofinalassessmentsinado- lescence,butwithreductionsofcorticalthicknessatallas- sessments(Shawetal.,2006).Atypicaldevelopmentalpat- ternsofbrainanatomyinindividualswithpersistentADHD have been reported for subcortical regions andthe cere- bellum(Castellanosetal.,2002;Mackieetal.,2007;Shaw etal.,2014).Anotherstudyfounddivergentdevelopmental trajectoriesfromage4through19yearsforADHDpersisters andcontrolindividualsinthebasalgangliafromchildhood toadulthood:theADHDgroupshowedasmallersurfacearea in childhood and a progressive atypical contraction com- paredtothecontrolgroup,whichinsteadshowedanexpan- sionwithage(Shawetal.,2014).Asimilardevelopmental trajectorywasfoundforcerebellarvolume,whereindivid- ualswithpersistentADHDshoweddecreasesinvolumefrom childhoodtoadolescence/youngadulthood,whichwerenot observedincontrolindividuals(Mackieetal.,2007).Further MRIstudieshaveexaminedthedevelopmentofthecorpus callosumandcorticalsurfaceareaandgyrification(Gilliam et al., 2011; Shaw etal., 2011), but without distinguish- ing between persistentand remittent ADHD at follow up, whichmakesthefindingslessinformative.Littledataexist onthe continuityof functional brainalterations in ADHD.

A small-scale longitudinal EEG study (n=11 young adults withADHD)reportedthat,amongERPimpairmentsrelated toattentionalallocation,inhibition,andresponseprepara- tion observed in childhoodduring a cued continuous per- formancetest (CPT),only deficitsinresponsepreparation wereassociatedwithADHDinadulthood (Doehnertetal., 2013), without differentiating between persistent andre- mittentADHDatfollowup.

The prediction of future ADHD outcome (remis- sion/persistence)based onearly cognitive andneural im- pairments measured in childhoodwithin an ADHD sample (point 2) is important for early identification of those at

risk for worse long-term outcomes (van Lieshout et al., 2013), with an eye on optimising treatment. Studies ex- aminingsuchpredictionatshorttermindicatethatimpair- mentsinearlychildhoodinexecutivefunctions,especially inhibition and working memory, and in IQ predict ADHD symptoms in later childhood (Berlin et al., 2003; Brocki et al., 2007; Campbelland von Stauffenberg,2009; Kalff etal.,2002),whereasRTVduringaCPT does not(Vaughn et al., 2011). Studies investigating clinical outcomes of ADHDpersistence/remissionwithfollowupinadolescence andadulthoodhaveobtainedinconsistentresults.Morere- centfollow-up studiesof childrenwithADHDsuggest that RTV and working memory across different tasks in child- hood may predict ADHD symptoms and/or functional im- pairmentinadolescentsandyoungadults,evenwhencon- trollingforchildhoodADHDsymptoms(Sjowalletal.,2015;

van Lieshout et al., 2016a). This is inconsistent with re- sultsofstudiesexaminingpersistence/remissionofADHDas lateroutcome,whichfoundnoevidencefor associationof aggregated measures of executive function, sustained at- tention,inhibition,workingmemory,andRTVinchildhood andADHDpersistence/remissioninadolescenceandadult- hood (Biederman etal.,2009;Cheung etal.,2015b;Mick etal.,2011).Inafollow-upstudy,IQwastheonlycognitive measure in childhoodwhich predicted later ADHD persis- tence/remission,whilemeasuresofworkingmemory(digit spanbackward),sustainedattention(omissionerrors),inhi- bition(commissionerrors)andRTVfromreaction-timeand go/no-gotasksdidnot(Cheungetal.,2015b).Thepredic- tive valueof IQhasbeen replicatedin twoother samples ofyoungadults(Agnew-Blaisetal.,2016;Gaoetal.,2015), butnot inathird sample(Francx etal.,2015b).The only studytodatetoexaminethepredictivevalueofchildhood brainactivityonadultADHDoutcomeindicatedthatresting- state EEG measures in the theta and beta bands predict ADHDpersistence/remission(Clarkeetal.,2011),especially infrontalregionsimplicatedinADHD.

Asforpoint(3),theidentificationofcognitiveandneural processesunderlyingthetrajectoriesofpersistenceandre- coveryfromchildhood-onsetADHDduringthetransitionto adulthoodmayfurthercontributetothepreventionofnega- tivelong-termoutcomes.Ithasbeenhypothesisedthatthe persistenceof ADHDwould bepredictedby thedegree of maturationandimprovementovertimeinhigher-levelcog- nitive function, andlower-levelcognitive functions would be linkedto thepresence of ADHD in childhood irrespec- tiveoflaterclinical status(HalperinandSchulz,2006).In afollow-upstudyof almost100individualswithchildhood ADHD assessed withboth cognitive performance and EEG actigraphmeasures(meanageatfollowup18.30,SD1.60), ADHDremittersdidnotdifferfromcontrolsinhigher-level cognitivefunctions (e.g. workingmemoryand commission errors),butwerestillimpairedinmeasuresassociatedwith lower-levelcognitiveprocesses(RTVandperceptualsensi- tivity) andankle movement level (Halperin etal., 2008).

The latterfindingwassupported byasecond study inthe same sample, where RTV did notdistinguish ADHD remit- tersfrompersisters,bothofwhomwereimpairedcompared tocontrols (Bedard etal.,2010). Otherstudies, however, havenotfoundanassociationbetweenADHDremissionand improvements in executive functioning(Biederman etal., 2009),interferencecontrol(Pazvantogluetal.,2012),and

responseinhibition (McAuley et al., 2014).Working mem- ory impairments in young adults diagnosed with ADHD in adolescencecomparedtocontrolshavealsobeenobserved regardless of whether they still met an ADHD diagnosis (Roman-Urrestarazu et al., 2016). Further studies found, acrossdifferent cognitivetasks, that cognitive-EEGmea- suresofpreparation,intra-individualvariability(RTV),vig- ilance,and errorprocessing(mostlyreflecting lower-level cognitive functions) differentiated ADHD remitters from persisters assessed in adolescence and young adulthood (Cheungetal.,2016;James etal.,2017;Michelinietal., 2016a).Cognitiveandbrainactivitymeasuresofexecutive controlof inhibition, working memory,and conflict moni- toring (largely reflecting higher-level cognitive functions) were not sensitive to persistence/remission of the disor- der(Cheungetal.,2016;Michelinietal.,2016a).Assuch, thesestudiesmaysuggestthat(“lower-level”)preparation- vigilance– insteadofhigher-level– cognitivefunctionsmay bemarkersofADHDrecovery,followingthesymptomlevel atfollowup.

Large-scaleneuroanatomicalstudiesalsofoundevidence of differences between ADHD persisters and remitters in adolescents and adults in measures of brain volume and structuralconnectivity.ADHDremittershaveshownaslower rateofcorticalthinningfromchildhoodtoadulthoodcom- pared to persisters, such that brain dimensions may be moresimilartothoseof controlindividuals infrontal and parietalregions withage(Shaw etal.,2006; Shawetal., 2013).Structuralconnectivityimpairmentsintheleftcorti- cospinaltract,implicatedinthecontrolofvoluntarymove- ments,havebeenreportedinadolescentsandyoungadults withchildhoodADHDwithpersistenthyperactive-impulsive symptoms compared toindividuals with greater symptom improvements over time and control individuals (Francx et al., 2015b). In white matter tracts connecting vari- ous regions related tosensorimotor and higher-level cog- nitivefunctions,however,bothADHDpersistersandremit- tersshowedimpairmentsinadulthoodcomparedtocontrols (Cortese et al., 2013). Developmental pathways of brain functioningmayalsoshowpotentialabnormalities,assug- gestedbystudiesof adolescentswithadiagnosis ofADHD inchildhood,butlimitedevidenceisavailabletodate.Two studiesofadolescentsandyoungadultsreportedincreased resting-statefMRIconnectivityinADHDremitterscompared to controls in the executive control network, with inter- mediateconnectivity profilesin persisters (Francx et al., 2015a),andincreasedEEGconnectivityduringanexecutive controltaskinbothADHDremittersandpersisters(Michelini etal.,2017).Othersmall-scalefMRIstudiesfurthersuggest thatthalamicandcorticalactivationduringresponseprepa- ration(Clerkinetal.,2013)andcaudateactivation during working memory performance (Roman-Urrestarazu et al., 2016)maybereduced inboth ADHDpersisters andremit- ters.Instead,lowerfunctionalcorrelation betweenposte- riorcingulateand medialprefrontal cortices(major com- ponents of the DMN) during rest (Mattfeld et al., 2014), lowerconnectivitybetweenthethalamusandprefrontalre- gionsduringresponsepreparation(Clerkinetal.,2013),and loweractivationsinareasoftheprefrontalcortexinvolved inreward processing (Wetterling etal.,2015)may distin- guishADHDpersistersfromremittersandcontrols.

Overall, despite some inconsistencies between studies, someconvergenceforcognitiveandneuroimagingmarkers ofADHDpersistenceandremissionisstartingtoemerge.For example,themajorityofstudiestodateshowthatimpair- mentsinexecutivefunctiondonotdistinguishADHDremit- tersandpersisters(Biedermanetal.,2009;Cheungetal., 2016; McAuley etal.,2014;Michelinietal., 2016a,2017; Pazvantogluetal.,2012).Aparticularlycriticalissue,likely explainingsomeofthediscrepanciesacrossstudies,isvari- abilityinthewaythepersistenceandremissionaredefined, as studies differin the use of parent- or self-reports and onwhetherfunctionalimpairmentistakenintoaccountat follow-up assessments. However, thereis a relatively low agreement between self- and parent-reports of ADHD in adolescentsandyoungadults,andobjectivecognitiveand neurophysiological datashowloweragreementwithADHD outcomeinadolescenceandyoungadulthoodbasedonself- reportthanonparent-report(DuRietzetal.,2016).

8. The role of genetic and environmental risk factors and their interplay in ADHD across the lifespan

Whileinvestigationsintothedynamicsofcognitiveandneu- roimagingmarkersacrosslifehavegainedtraction,there- search intolifespan aspectsof underlying risk factors for ADHD is stillvery much in itsinfancy. ADHD has a strong geneticcomponent.Familystudieshaveconsistentlyshown familial clustering,withan ADHDrelativerisk of about 5- to10-fold infirst-degree relativesof probandswithADHD (Biederman, 2005;Biederman etal., 1990; Frankeet al., 2012).Twinstudiesshowheritabilityestimatesbetween70%

and80%, andtheunderlying geneticarchitectureofADHD appears similaracrossthe differentcore symptomdimen- sionsandgender(Faraoneetal.,2005;Larssonetal.,2014;

NikolasandBurt, 2010).Consistentevidencesupportssta- bilityintheADHDheritabilityacrossthelifespanestimated using thesameinformantacross agesandcross-informant approaches(Brikelletal.,2015;Changetal.,2013;Kuntsi etal.,2005).

Given themultifactorial,polygenicnatureofADHD,ge- netic research has mainly focused on common variants throughhypothesis-drivencandidategeneassociationstud- ies (CGAS) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with case-control or family-based designs. These designs consist on observational studies in which the frequencies ofspecificcommongeneticvariantswithincandidategenes forADHDoragenome-widesetofpolymorphismsarecom- pared betweenaffected (cases)and unaffected(controls) individualsorbetweenaffectedsubjectsandtheirrelatives.

Several linkage studies have also been performed. They allow genetic mapping of complex traits showing famil- iar aggregationbyassessingthe co-segregationof thedis- easephenotypewithsequencevariantsacrossthegenome.

More recently, geneticstudies in ADHD have also focused on rare variation (allele frequency <0.05) through copy- numbervariant(CNV)analyses,whichinspectalterationsin genomic segmentsofmorethan1Kbinlength,andexome chipanalysisandwhole-exomesequencing,targetingpoint mutationsorsmallindels.Theseinvestigationshaveshown

converging evidence for common biological pathways un- derlyingADHD,whichhighlightsthatbothcommonandrare geneticvariantsaccountforasignificantproportionofthe geneticsusceptibilitytothedisorder(Martinetal.,2015b;

Stergiakoulietal.,2012;Zayatsetal.,2016).

To date, seven genome-wide linkage scans have been performed in ADHD. Although very little overlap wasob- servedbetweenanalyses,differentgeneticlocipotentially involved inADHD havebeen found onchromosomes5p13, 14q12, and 17p11, and a meta-analysis of ADHD linkage studiesconfirmed alocusonchromosome16(Zhouetal., 2008).Onlyfewpositionalcandidategeneshave,however, beenidentifiedfromtheselinkagescans,e.g.DIRAS2(Reif etal.,2011)andLPHN3(Arcos-Burgos etal.,2010). Also, althoughhundredsofCGAShavebeenreported,onlyafew findings have been consistently replicatedacross studies.

These studieshave focusedprimarily ongenesinvolved in neurotransmission,particularlyinthemonoaminergicpath- ways. Serotonin anddopamine receptors andtransporters arethemostextensivelystudiedandreplicatedacrosspop- ulations(Frankeetal.,2012;Gizeretal.,2009;Hawietal., 2015).Almost allstudieswere performedin children,and noneoftheresultingcandidategenescanbeconsideredas established.Oneofthefewgenestestedthoroughlyinboth childrenandadultsisthedopaminetransporter,andintrigu- ingly,opposite alleleswereassociatedwithchildhoodand adulthoodADHD(Frankeetal.,2010).

GWAS on ADHD have been completed in nine indepen- dentdatasets(Anneyetal.,2008;Frankeetal.,2009;Hin- ney etal.,2011; Lasky-Su etal.,2008;Mick etal.,2010;

Neale et al., 2008; Sanchez-Mora et al., 2015; Stergiak- ouli et al., 2012; Yanget al., 2013; Zayats etal., 2015), threeof them focusingonthe persistent formof thedis- order(Lesch etal., 2008; Sanchez-Moraet al., 2015; Za- yats etal.,2015). Althoughnone of them,nortwometa- analyses onseveralof these datasets (Nealeet al.,2010;

van Hulzen et al., 2016), reported genome-wide signifi- cance, the integration of top findings from the different studies showed enrichment of genes related to neurobi- ological functions potentially relevant to ADHD, such as neurite outgrowth, central nervous system development, neuronaldevelopment,differentiationandactivity,neuron migration,synaptictransmission,axon guidance,Calcium- activated K+ channels, FGFR ligand binding, and activa- tionor potassium channels, amongothers(Mooney etal., 2016;Sanchez-Moraetal.,2015;Yangetal.,2013;Zayats etal.,2015).Forthefirsttime,averyrecentGWASmeta- analysisin20,183ADHDcasesand35,191controls,includ- ingchildrenandadultsfrom12datasets,reportedgenome- wide significant hits in 12 independent loci that include genes involved in neurodevelopmental processes,such as FOXP2orDUSP6,andevolutionarilyconservedgenomicre- gions (Demontis et al., 2017). Limited overlap exists be- tweenresultsofGWASandpreviousCGASorlinkagestudies, andaseparate analysisfor thepersistingversus remitting formsofADHDisstilllacking.Thus,thegeneticarchitecture underlying the lifespan trajectory of ADHD is still largely obscure.

Although each of the ADHD-associatedvariants appears toaccountfor asmallproportionofthevariance inADHD symptoms,SNPswereestimatedtoaccountfor10%to28%

oftheheritabilityofthedisorder(Anttilaetal.,2018;De-