UNIVERSITY OF DERBY

STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT IN URBAN TOURISM DEVELOPMENT

A TALE OF TWO CITIES

Ágnes Raffay

Doctor of Philosophy 2007

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Tale of Two Cities... 1

Chapter 2: Developing Urban Tourism ... 8

Tourism development... 15

Urban tourism... 35

Chapter 3: Perspectives on Collaboration... 40

Forms of collaboration ... 42

Collaboration in the tourism literature... 47

Collaborative capacity ... 50

Chapter 4: Stakeholder Theory... 59

The emergence of the stakeholder theory... 59

Stakeholder groups ... 63

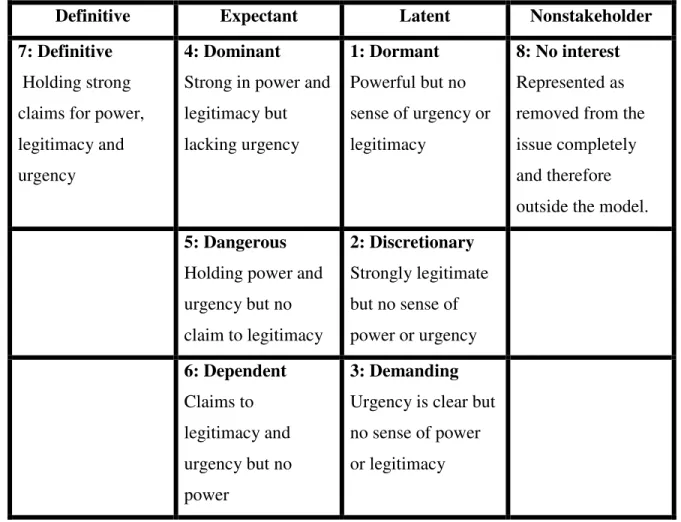

Typology of the stakeholder theory... 68

Stakeholders in the tourism literature ... 70

Chapter 5: Exploring Power and Related Concepts... 80

Weber's theory... 81

Lukes analysis of power ... 85

Foucault on power ... 90

Power in practice - Clegg's theory... 94

Power in tourism... 98

Chapter 6: Methodology and Research Design ... 104

Schools of thought... 105

Qualitative and quantitative research approaches to methodology... 111

Research philosophy... 117

Quality of the research design ... 121

Triangulation ... 128

Research strategy... 132

Research design... 133

Data collection... 139

Data analysis... 142

Primary research used for the purposes of this study ... 147

Chapter 7: Backgrounds and Context... 152

About Hungary ... 152

Pécs... 155

Veszprém... 157

Organisational structure of tourism in Hungary ... 162

Organisational structure of tourism in the two cities... 168

Chapter 8: Mapping the Tourism Stakeholders in the Two Cities... 175

Stakeholder component 1 ... 175

Stakeholder component 2 ... 191

Stakeholder component 3 ... 201

Amalgamating the components of the stakeholder notion... 208

Chapter 9: Analysing Stakeholder Involvement in the Two Cities ... 210

Stakeholders involved in tourism development... 211

Relationship between the actors ... 220

Ladder of stakeholder involvement in tourism development... 232

Chapter 10: Stakeholders and the Analysis of Power... 235

The perspectives on tourism development in the two cities ... 236

Discourses of power ... 239

Formal institutions and the discourses of power ... 244

Relationships and the discourses of power ... 251

Types of authority based on the Weberian theory ... 255

The dimensions of power in the two cities ... 258

Power in practice: an elaborated examination ... 273 Chapter 11: Conclusions, Propositions and Future Research Agendas ... 285 References ... 298

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

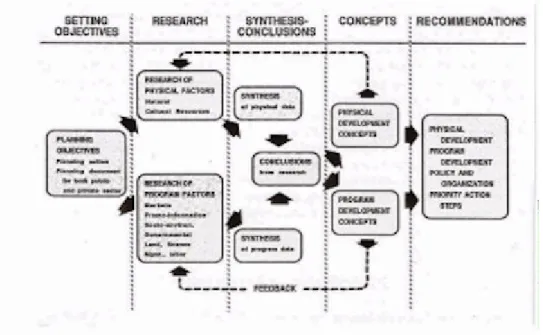

Figure 2.1 Key steps of regional tourism planning 22

Figure 2.2 Continuous planning 24

Figure 2.3 The tourism planning process 25

Table 2.1 A continuum of commitments to sustainability 29

Table 2.2 A bipolar view of tourism planning approaches 31

Table 2.3 Five dilemmas for the future of social democracy 32

Table 2.4 Burns' third way 34

Table 2.5 Primary elements of urban tourism 37

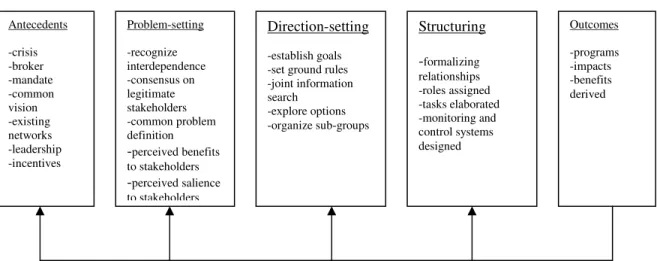

Figure 3.1 An evolutionary model of tourism partnerships 43

Table 3.1 Advantages and disadvantages of collaboration 51

Table 3.2 Conditions of partnership development 51

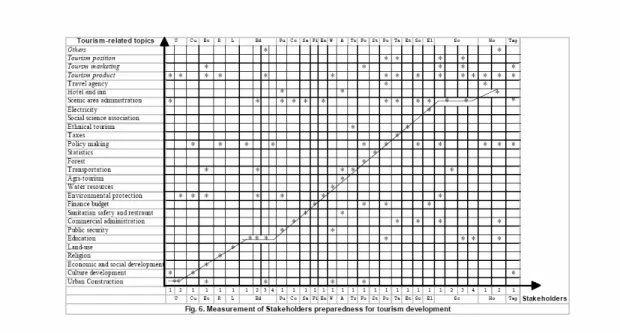

Figure 3.2 Measurement of stakeholder preparedness for tourism development 55

Table 3.3 Pitfalls of collaborating and not collaborating 57

Table 4.1 Classical stakeholder grid 65

Table 4.2 Stakeholder types 67

Table 4.3 Business stakeholders identified in the literature 70

Table 4.4 Tourism stakeholders identified in the literature 73

Table 5.1 Sources of legitimacy 82

Table 5.2 Obedience, laws and management groups in the different types of authority 84

Table 5.3 Typology of power and related concepts 87

Table 5.4 The three dimensions of power 89

Figure 5.1 The theoretical contexts of the analytical framework 100

Table 6.1 Two schools of science 106

Table 6.2 Key scholar define ontology, epistemology and methodology 107

Table 6.3 Philosophical approaches vs paradigm elements 107

Table 6.4 Criticisms of positivism 109

Table 6.5 Strengths and weaknesses of a positivist approach 109

Table 6.6 Strengths and weaknesses of phenomenology 110

Figure 6.1 Continuum of research philosophies 111

Table 6.7 Key features of paradigms 111

Table 6.8 Qualitative and quantitative research 113

Table 6.9 Qualitative techniques and methods and their uses 114

Table 6.10 Theory building in qualitative and quantitative research 115

Table 6.11 Positivist vs phenomenology 116

Table 6.12 Quantitative and qualitative approaches to research 119

Table 6.13 Case study tactics for four design tests 122

Table 6.14 Steps and actions towards ensuring the quality of research 124

Table 6.15 Actions undertaken for the quality research criteria 126

Table 6.16 Organisation research barriers and actions taken 127

Table 6.17 Action taken to minimise triangulation limitations 130

Table 6.18 Triangulation perspectives 131

Figure 6.2 The four issues affecting the research strategy 133

Table 6.19 Securing sources of evidence for case study research 136

Figure 6.3 Generic model case study design 137

Figure 6.4 Interactive/Interrelated model implement in data analysis 144

Table 6.20 Quality of analysis and actions by researcher 144

Figure 7.1 The map of Hungary 152

Figure 7.2 National, regional and governmental posts responsible for tourism in Hungary 162

Figure 7.3 Tourism responsibilities in Pécs 168

Figure 7.4 Tourism responsibilities in Veszprém 171

Table 8.1 Stakeholder component 1 (key players of tourism) in Pécs 176

Table 8.2 Stakeholder component 1 (key players of tourism) in Veszprém 183

Table 8.3 Stakeholder component 1 (key player) in the two cities 190

Table 8.4 Stakeholder component 2 (affected by tourism) in Pécs 192

Table 8.5 Stakeholder component 2 (affected by tourism) in Veszprém 196

Table 8.6 Stakeholder component 2 (affected by) in the two cities 200

Table 8.7 Stakeholder component 3 (involved in tourism development) in Pécs 201 Table 8.8 Stakeholder component 3 (involved in tourism development) in Veszprém 203

Table 8.9 Stakeholder component 3 (involved in) in the two cities 207

Table 9.1 Stakeholder component 3 (involved in) in the two cities 211

Table 9.2 Emergent actors in Pécs 212

Table 9.3 Emergent actors in Veszprém 213

Table 9.4 A comparison of identified and emergent actors in the two cities 215

Figure 9.1 Ladder of stakeholder involvement in tourism development 233

Figure 10.1 A formal power pyramid 266

Figure 10.2 The open tourism organisation in Pécs 268

Figure 10.3 The open tourism organisation in Veszprém 269

Figure 10.4 A possible power pyramid in Pécs 270

Figure 10.5 A possible power pyramid in Veszprém 271

Figure 10.6 Discursive constructions of power as reinforcing and challenging 277

Figure 10.7 Stakeholder positioning in complex circuits of discourses 278

Figure 10.8 The analytical framework 281

Figure 10.9 A partial elaboration of one of the fields of analysis 282

PREFACE

Statement of Intellectual Ownership

The work presented here is the original work of Ágnes Raffay, conducted between 2001 and 2007, and submitted for consideration for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in March 2007.

The work was examined on the 11th of May, 2007 with Professor Don Getz (University of Calgary) and Professor David Crouch (University of Derby) conducting the viva voce.

The award was made with effect from the 16th of May, 2007.

ABSTRACT

This thesis began with the identification of a challenging issue in the practical management of urban tourism development. The debates about how to manage urban tourism, the benefits of collaboration and partnership building were interesting but seemed to be interpreted differently in both the different strands of the literature and in the specific destinations. The focus on stakeholders was an emergent theme from the literature. It had become a significant term in the business and management literature and was, following on the work on collaboration and sustainable tourism, becoming a popular term in the tourism literature. However it was apparent from studying the literature that the term was both complex and under theorised, especially in the tourism literature.

Therefore the literature review was designed to identify the context in which stakeholders existed and in which stakeholder analysis could take place. The way in which the issues were generated for the field work was the product of critical readings of the texts.

The review suggested that the dynamics of urban tourism were very complex and more so than stakeholder analysis predicated on a single organisation would suggest. The range of positions within the process suggested that terms such as involvement, participation and collaboration had to be questioned in terms of power relations and power differentials in what emerged as processes rather than a single process. The questioning of the power literature suggested that a discursive approach to the construction of stakeholder analysis would be the most appropriate as the key players sought to develop their sense of power from within a range of discourses and the flexibility of such accounts offered an appropriate way to capture the fluid dynamism of the urban tourism processes.

A field methodology based on qualitative research was developed to allow the respondents, who were identified as the key players in tourism in the two Hungarian cities, the opportunity to create their own representations of the ways they saw tourism development in their two cities. Two case studies were pursued as a way of highlighting similarities and differences in the processes, in the patterns of involvement and the power relationships.

The conclusions develop an account of power that is constructed and deconstructed within urban tourism processes by the exercise of discursive constructs from both within and outside the domain of tourism. Even traditional accounts of power fitted into the discursive practices analysed. Thus, the thesis has developed an original contribution by deepening our understanding of the concept of stakeholders within urban tourism development and seeking to establish that a critical understanding of discursive practices is an integral part of mapping the stakeholder positions within those processes. A series of propositions are presented that represent the major contributions of the thesis to tourism knowledge and management knowledge. These are presented in a standardised format of establishing the basis of the claim and then exploring the implications for practice and further research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, .. .”

Dickens (1859:1) A Tale of Two Cities

I would like to express my gratitude to the following people for helping me through the

‘worst of times’:

Professor Alan Clarke for constantly asking difficult questions but always the right ones;

Tim Heap for his guidance and supervision, the colleagues from the Universities in Derby and Veszprém;

To the University of Derby, through the School of Tourism and Hospitality Management as it then was for the bursary that allowed this research to take place;

To all the people who gave of their time to make the work possible;

My family for their support above and beyond the call of duty;

Dan and Alex for their patience and reassuring smiles;

The friends who have supported me through this rollercoaster ride. There are many of them, too many to name individually, but you know who you are and thank you!

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Tale of Two Cities

This is a tale of two cities – two Hungarian cities that offer great potential for tourism with their fine cultural heritages. The tale will entail a lengthy discussion of the characters and the relations between these characters, it will consider the factors that complicate these relations as the plot unfolds.

This research emerged from the author’s direct experience of the processes of urban tourism in her capacity as a local authority tourism referent. The interest in the role of stakeholders within tourism developed further with participation in a European funded urban tourism project. DETOUR – developing tourism in urban Europe – which brought together six cities to critically benchmark and evaluate their approach to tourism, including the tourism offer, the tourism marketing and the planning of tourism in the cities. This highlighted considerable differences in the way the notion of ‘important’ or

‘key’ players were identified in the various cities which were not considered during the project. The best practice model proposed at the end of the project was clearly grounded in the literature on the benefits of partnership working with an inclusive agenda for participation in the decision making about urban tourism development.

By telling the tale of two cities the study is going to focus on stakeholder involvement in urban tourism development. The extensive literature review is going to consider the emergence of stakeholder theory, based primarily on the writings of academics in the management discipline (Freeman, 1984, Carroll, 1996, Key, 1999, Schilling, 2000) but also with reference to the tourism literature (Jamal and Getz, 1995, Swarbrooke, 1998, Bramwell and Sharman 1999, Sautter and Leisen, 1999, Friedman and Mason, 2004).

The stakeholder theory calls into question the need to investigate issues of power therefore, modern power theories (Weber (1978; 2003), Lukes (1974), Foucault (1972;

1988) and Clegg (1989)) are going to be discussed to gain a better understanding of the power relations between stakeholders. The literatures on collaboration theory (Gray, 1989, Jamal and Getz 1995), tourism planning (Gunn, 1994, Inskeep 1994 and Tribe, 1997, Burns, 2004) and stakeholder involvement (Murphy, 1985, Bramwell and Sharman

1999), along with urban tourism (Jansen-Verbeke, 1986, Page, 1995, Pearce, 2001, Law, 2002) also form the theoretical background of the thesis.

Primary research is based in two Hungarian cities, Veszprém and Pécs. The choice of cities has been influenced by several factors. Primarily, the researcher graduated as a tourism student in Veszprém and worked in the tourism industry there for three years before embarking on this study. First as an assistant in the city’s tourist information centre Tourinform and later as a tourism referent of the local authority (advisor to the Mayor in tourism related issues); she had an insight into how tourism development is shaped by certain enabling and restricting forces. This experience led to the desire to investigate whether this is unique to Veszprém or if other cities operate with similar methods. The scholarship from the University of Derby made the city of Derby a logical choice for the comparison. Within the UK, it was thought that York, a historic city with an established tradition of welcoming tourists, would be a useful part of the study.

However, the review of the literature on stakeholders and tourism development and the discussion with the PhD supervisors suggested another idea for exploring: whether or not the existence of a tourism strategy influences the involvement of stakeholders in the tourism development processes. As most UK cities with a significant tourism industry would have a tourism strategy in place, it seemed a better bet to look for another Hungarian city with similar characteristics to Veszprém but without a strategy. Pécs fitted the selection criteria, therefore at that stage the research was going to focus on four cities, Veszprém, Derby, York and Pécs. The decision followed the recommendation of the School Research Degrees Committees to the RD5, where the Committee suggested looking at stakeholder involvement in a city without a tourism strategy.

As the first round of interviews were conducted in Veszprém and Pécs, the researcher found significant similarities between the responses from the two cities, or better phrased there were not enough significant differences emerging from between the responses from the two cities, furthermore, there were no differences discovered that could have been explained by the existence or lack of a tourism strategy.

The analysis of the first interviews has revealed considerably more information than the researcher had hoped for. Also, neither the literature, nor the findings of the interviews conducted thus far suggested any difference in stakeholder involvement that would be influenced either by the size of the city or the existence of a tourism strategy. Therefore, it was argued that the involvement of a third and fourth city in the research may only enhance the quantity of the data, without adding extra value to the research. It has been decided that the study would benefit more from an in-depth analysis of the power hierarchies and the role of the individual stakeholders within them. This was reinforced by the RD7 Confirmation of Progress discussions, with the recommendation to conduct interviews with at least the key actors from the main sectors (public, private, academic) in Derby to test the above statement about quantity versus quality of findings. The field work in York and the four interviews in Derby brought up remarkably similar issues to what had been revealed in Veszprém and Pécs before, therefore the research did not seem to benefit from the involvement of a third city. The work on the two cities in the UK proved to be a useful testing ground for the ideas and methods used in the studies in Hungary, but the decision to drop the two from the full study was made on the grounds of securing the best possible data and the opportunity to critically review it. It appears that the UK material would have reinforced and largely replicated the critical elements of the study without adding further dimensions to the study.

It was decided that the study would benefit more from an in-depth analysis of the power hierarchy and the role of the individual stakeholders within it than from the assessment of the strategy devising process as well, which could have presented a risk of losing the focus of the research and the clarity of the responses. The introduction of the concept of stakeholders was provocative enough, when it is recognised that there is no word in Hungarian for ‘stakeholder’. This meant that the research involved a deconstruction of the literature concept into its constituent elements that did translate into the language of the respondents and then a reconstruction of the applied concept through the answers given in the interviews. To undertake a similar approach with the ideas of strategy and strategic management was thought to be too ambitious for one PhD and therefore the focus intensified on the identification of key informants’ perceptions about the nature of

involvement in the urban tourism development of the cities. Therefore the study that is presented has been concentrated on the two Hungarian cities and the arguments about stakeholder involvement developed within those cities. The interviews conducted in Derby and the materials collected from York were used to sharpen the analytical perspective developed through the research but are not specifically included here. The depth of the materials gathered from Pécs and Veszprém produced a rich field of data, identifying both similarities and differences in the ways stakeholders were involved in urban tourism development.

The initial research was focussed into the formulation of the research aims:

• To determine the notion of stakeholder in tourism and the parameters of the concept;

• To identify the stakeholders in urban tourism and investigate the power relations between them;

• To critically evaluate the level and limitations of stakeholder involvement in urban tourism development.

These aims were the product of extensive discussions in the University and were also aired before tourism practitioners to ensure that they gave the research the most appropriate framework. They proved to be a useful guide to the development, implementation and analysis of the research.

The study will use a case study approach (Yin 1994, 2003). As the number of cities involved in the research does not allow for generalisations, the findings on power relations and stakeholder involvement in the cities will be presented in a case study format.

The thesis appears to fall into three distinct parts but the development of the argument relies upon the successful interlinking of these parts. The first part, Chapters 2 – 5, present the review of the literatures, moving from the general approaches to the macro issues of urban tourism development (Chapter 2) through the issues of collaboration (Chapter 3), constructions of stakeholders (Chapter 4) and concepts of power (Chapter 5).

The analysis is presented in these three sections to allow the reader to become familiar with the critical understanding of the term stakeholder developed from the literature and how those models sit with other concepts of urban tourism and urban tourism development. The literature review identified the trends towards partnership working as particularly significant and also noted the need to establish a firm theoretical grasp of the concepts of power and involvement. Even within these chapters it will be apparent that the research object contains several elements that can be thought of separately for the purposes of exposition. However, in practice the elements overlap the distinctions imposed on the literature in these reviews and it is the interconnections between the issues that fully express the complexities involved in the development of urban tourism.

This recognition is fundamental given the assumption underlying the thesis that tourism is a complex entity with a multitude of actors and a myriad of offers. Chapter 5 ends by bringing together the elements from the whole of the literature review and putting together an analytical framework that is taken forward to drive the empirical study.

The second part considers the issues that are necessary for the study. Chapter 6 outlines the research methodology and the methods devised to deliver this work. It reviews the epistemological issues as well as the practical concerns of undertaking the research. This critical review of the approach also contains an account of the ways in which the deconstruction of the literature provided the framework for the questions posed. In the following chapter, there is a short introduction to the background and contexts of the research. The intent is to create an impression of the two cities where the research took place and the structures of tourism in Hungary.

The third section moves on to the presentation of the analysis, moving through an analytical description of the responses in constructing a listing of the stakeholders in Chapter 8, to a consideration of collaboration and capacity in Chapter 9. Chapter 10 presents the major findings on power, power relations and constructions of power within the urban tourism contexts in the two cities. The presentation of the findings from the interviews is iterative, showing first the patterns of responses to the questions and then further analysing them to reveal the significance of the comments.

Primary data was gathered through semi-structured interviews with key informants who were identified primarily on the basis of the literature, and a snowball technique was used as a secondary selection method to identify the interviewees.

The first subject area that the fieldwork tried to establish was the identification of stakeholders in the given city. The second area to be explored looked at the links between the previously identified stakeholders. The questions hoped to reveal information on both the formal and informal relations between the key players and the affected organisations and people, as perceived by the respondents. The third area was investigating the involvement in the urban tourism development in the cities. These questions sought to identify the key decision-makers and to depict the process, again, as perceived by the individual respondents. These answers gave information regarding involvement, legitimate stakeholders, and power in decision-making.

These findings are presented in three chapters which link closely to the concerns identified in the three chapters of the literature review. The first one presents the identified stakeholders in separate lists for both cities, which are worked into a joint list for urban tourism stakeholders. The second chapter discusses the perceptions of the respondents regarding involvement in urban tourism development, with special attention to the relations between the stakeholders. This chapter also looks at the issues concerning tourism collaborations. The third chapter analyses the distribution of power between the identified stakeholders which will help to get a better understanding of the conditions of involvement. The power-related findings are used to map the power relations between the stakeholders. The responses are organised in four different ways: 1) identifying the Foucauldian discourses, 2) mapping the stakeholders according to Weber’s categories of power (bureaucratic, traditional, charismatic), 3) investigating the three dimensions of power established by Lukes, and 4) assessing the distribution of power in the open organisations of the two cities relying on Clegg’s theory.

The outlined chapters enable the researcher to provide a new definition of urban tourism

stakeholders and devise a model of stakeholder involvement in urban tourism development.

The original contribution of the research will be provided by an elaborated stakeholder definition for tourism, the identification of stakeholders in urban tourism and a critical understanding of current practices and limitations of stakeholder involvement in urban tourism development. The conclusions to the thesis are presented in the form of a series of propositions that demonstrate the contributions to knowledge made, issues for practice and suggestions for further research.

The process of telling our tale has served to underline the complexity of tourism and the interrelationships within tourism. We begin in the next chapter with the opening pages of the discussions about urban tourism development.

Chapter 2: Developing Urban Tourism

In undertaking the literature review that informs this study it was important to pay attention to the sets of literature that:

a) establish the field of study b) identify emergent concepts

c) highlight neglected, under researched and absent elements.

The four chapters of the review have been designed to move through these sets, from the macro level concerns with urban tourism development through to the micro level issues of involvement, collaboration, power and stakeholder definitions in order to produce a narrower and sharper focus to address the aims of the research. The separation has produced its own difficulties as the literatures are interconnected and difficult to disentangle. Hence the notion of stakeholder is introduced before the chapter seeking to explore its elaboration. This makes for difficulties in authoring but serves to reinforce the notion of complexity and interconnectedness that underpins all aspects of this study.

The research aims identified were:

• To determine the notion of stakeholder in tourism and the parameters of the concept;

• To identify the stakeholders in urban tourism and investigate the power relations between them;

• To critically evaluate the level and limitations of stakeholder involvement in urban tourism development.

Each of these aims addresses and examines the idea of stakeholders as being central to the processes of tourism development. This literature review will present a critical account of the emergence of the stakeholder concept in tourism studies as a way of establishing the parameters of the concept that underpins the empirical study that follows.

In the first section, this Chapter explores the ideas of tourism development and assesses the urban context of tourism. This defines the field in which the study takes shape. The field can be seen as constructed by notions of planning that have concentrated on organisational and procedural approaches, neglecting questions of interest and agency that are essential to stakeholder analysis. The second part, Chapter 3, looks at the issues

of participation and capacity and the concept of collaboration which has become increasingly significant in management studies as one way in which stakeholders might overcome differences of interest to work together productively to define and achieve common goals. Collaboration has a complicated relationship to questions of power: some commentators suggest collaborative working can overcome power differences, while others suggest that inequalities of power shape, or are reproduced in, collaborative processes. The following Chapter 4 examines the development of the stakeholder concept, with particular attention to its use in approaches to tourism development. This discussion raises questions about the relative neglect of questions of power and power differentials in stakeholder analysis. Consequently the final Chapter 5 considers theories of power, centring on the work of Weber (1978; 2003), Lukes (1974), Foucault (1972;

1988) and Clegg (1989). These approaches and their implications for studying power in practice provide crucial orientations for the empirical study of stakeholders. One of the key issues identified in the tourism literature was the different ways in which power was used in the accounts and how in many it was a significant absence. The chapter concludes by drawing out the analytic objectives that shaped the empirical study of tourism development in the two cities that is reported and discussed in the subsequent chapters.

This chapter will present a critical consideration of the literature in the fields of tourism development and urban tourism studies. These two areas were researched but it should be noted are not the primary focus of the study. However they are essential to the construction of the context of the research. This discussion is therefore not intended to offer comprehensive accounts of the fields but has been included to demonstrate how the two different literatures present issues which are relevant to and inform the research development of this study.

Firstly it is important to establish the limits on the terms being used in this review. Urban tourism development has generally not involved the macro level discussion of development that informs studies of Third World development (Roberts and Hite, 2007) Although the significance of development theories and globalisation arguments (Dicken et al., 1998, Wahab and Cooper, 2001) are recognised, they are not taken to be central

issues in the construction of the framework of this study.

We must explore carefully what this term globalisation means, as it appears that there are different ways of using the same term, which have very different impacts on the way the issue is presented. Three important aspects of globalisation seem to emerge from the literature that impact on tourism:

1. Globalisation as homogenising force (McDonaldisation theses for example)

2. Globalisation as an opportunity for facilitating access to important markets for new entrants and old players

3. Globalisation as the discourse of success - a self-fulfilling prophesy.

As academics write about globalisation, they appear to have two different models of the process open to them (MacLeod, 2004). One sees globalisation as a distinct process - something which is happening to the world. The other sees globalisation as an intensification of changes which are taking place in society as a result of other identifiable forces (Rosenberg, 2002).

The first model of globalisation as a distinct process (De Beule and Cuyvers, 2005) is most powerfully seen embodied in the ‘disneyfication’ argument, where it is seen that Disney is transforming the world. This version of globalisation sees a process where global corporations are producing and reproducing a world in their own image (Dunning, 1993). The businesses - and this would include tourism businesses - are operating in a market which is no more than an extension of their own back garden, but that market place has been extended across the world and constructed in their own conditions (Davis and Nyland (eds), 2004). One key factor involved in these accounts is the role of technology in facilitating participation in this global system (Roy, 2005). A critical account of this thesis can be found in Ritzer’s accounts of McDonaldisation (1993, 1998 and 1999). Here globalisation offers the promise of worldwide standards in service provision, with the promise or threat of not disappointing the customers’ expectations where ever they are.

The second model sees globalisation as the summation of a range of other processes

which are happening within the societies of the late Twentieth and early Twenty First Centuries (Hoogevelt, 1997). There are political processes which are taking place alongside this (Smiers, 2003). There are processes which change the way that social life is lived - access to satellite and cable broadcasting networks opened up mass communications in a way which has revolutionized the way the broadcasting system works today (Hirst and Thompson, 1995).

There is a possible third view of the processes of globalisation, which sees

“globalisation” as a discourse. The importance of discourse for this account is that discourses have a power in themselves and in particular they have the power to shape the

“lived realities” of people’s everyday life. These realities do not exist until they are constructed by people interacting in and through social processes (Jameson and Miyoshi, 1998). Moreover, those processes then assume a reality and you get to the really important point about what they have been creating as the more people buy into a discourse the more power those discourses have.

These definitions of the globalisation process must be questioned. However in asking the questions, it must be recognised that there are certain effects of the globalisation discourse which are affecting hospitality and tourism on three levels. These levels are:

the expectations of the guests, the expectations of the locals and

the opportunities which may exist because of these changing expectations.

The expectations are different for both the international guest and the domestic guest - what is the domestic tourism experience in the region? It is necessary to consider what has traditionally been the domestic tourism experience and what the expectations are now? How that is changing with the expectations that come with the global process is an important aspect of the cultural dynamic?

Globalisation also makes things available - it puts into place an international infrastructure which makes things possible. It is an infrastructure which makes the changing expectations realizable (Olds et al, 1999). It changes the opportunities open to

people and it changes the availability of those opportunities. What is more important than studying the global at the global level is to look at the ways in which it impacts on people’s lived realities (Whalley, Anderton and Brenton, 2006). When you examine the way that people live their everyday lives, what you see is that discourse of the globalisation processes cut right the way across every day life. It constructs civil society in new ways, but it has to be recognised that the impact is differently experienced locally.

The changes are re-presented in many different ways depending on the local contexts upon which the processes are being mapped and the discourses read. It will be different in Hong Kong from Beijing, from Kuala Lumpur, from Manila and from Bangkok and Birmingham. It is different regionally as well as locally and it will be different between countries. There will be as many differences - if not more - than there are similarities - across regions and certainly across nation states.

If anyone suggests that there is a monolithic process called globalisation and that, as a result, we will all be the same a few years down the line - do not believe them (Robertson, 1992). That observation is predicated upon a notion that the power of the economic is total and that it will be the force that determines the future. Economics is not the only social process involved (Gangopadhyay and Chatterji, 2005). Development theory introduced the notion of core and peripheral regions, centres that were the ‘core’

of the civilising and development processes and peripheral regions which supported the continued development of the core (Peet, 1991). In the good old days, the UK could be seen as a core with the colonies as the periphery. The same patterns of development can be seen across the Asia Pacific region, not only with colonial core periphery regional relations but also between strong national capitals and peripheral regions within the nation state. It is also possible to propose that there is a core for the Asia Tiger economies and then a periphery within the region which has supported that development.

International tourism has seen the impact of the first two aspects very powerfully - the tourist infrastructure has been shaped by global operators introducing the style and expectations of the dominant tourist exporting nations throughout the world. However, these developments have not all been undertaken by established multinational

corporations and tourism continues to be inspired by a multitude of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). These SMEs have added a great deal to the dynamism of the tourism sector and to the diversity of the touristic offer. We have to recognise the dangers of domination and the possibilities of dynamism that globalisation can produce in understanding the growth and future development of tourism.

The third aspect of globalisation is the dangerous one for tourism. If people come to accept the discourse of the global, we will lose a great deal that is valuable and is argued to be vital to the success of tourism. If we accept the credo that the global solution is the answer to tourists' demands, then we will allow the creation of a tourism offer that is standardised and recognisable the world over. Disneyland is an important part of tourism but we do not all have to offer Disney or a Disney clone to operate successfully within the tourism industry.

Trends in international tourism support this and suggest that the globalising forces may have reached a point of resistance (Poon, 2003). Tourists are arguing that they want to see greater choice and take more control of their experience than previously. Mass tourist packages are still important but independent and self-directed tourism is becoming more popular. Moreover, the destinations for the tourists are changing, the traditional destinations are still important but we are witnessing a trend towards more but shorter breaks focussed on interest and activity motivations. We will explore some of the elements that allow cities to construct distinctive identities and how these can be exploited within the global tourism market.

Urban tourism does not exist outside these pressures as Fainstein and Judd (1999:12–13) have observed. The “globalization of mass tourism leads to an odd paradox: whereas the appeal of tourism is the opportunity to see something different, cities that are remade to attract tourists seem more and more alike.” In Singapore, Chang (1999:93) noted that

“both globalisation and localisation are occurring simultaneously with the outcome being a conflation of homogenising and localising influences in places.”

It is necessary to rehearse some of the assumptions which have been made in the construction of this study about tourism and about the nature of tourism. Svensson et al (2005:32) argued five assumptions could be identified that informed studies of tourist destinations and their development process. They summarised them as: “

a) There is a multi-actor complexity of the destination that needs to be taken into account.

b) It is also likely that certain resource dependencies between the actors involved are important dynamic factors of the process and need to be understood.

c) The public-private dimension of the destination may be important; i.e. the role of government vis-à-vis firms needs to be taken into account.

d) Who is in control and the leadership aspect are open issues in destination development

e) Destination development is a process with low predictability in regard to outcomes.”

These assumptions will also operate in the study of urban tourism. There is always a debate about what constitutes urban tourism as a subset of tourism linked to spatial definitions of location or to identifying motivations for tourism with particular attributes.

Here, following Ashworth (1992), urban tourism is taken to relate to the setting and the associated activities that occur there, including all tourism impacting on the urban environments of the two cities, so includes motivations which are not specifically related to the urban area. This is important in management terms as both cities attract large numbers of tourists from areas outside the city who would not be defined as urban tourists. However, the presence of these tourists in the urban domain shapes both the management of tourism and the definition of the offer. The question of definition echoes the debate in the pages of the Annals of Tourism Research about studies of Heritage tourism (Garrod and Fyall, 2000; Poria, Butler and Airey, 2001; and Garrod and Fyall, 2001). At the end of which Garrod and Fyall (2001:1051) conclude: “of far greater importance is the recognition of the proper place of definitions in tourism research. As we have argued elsewhere (Garrod and Fyall, 1998), the real danger in concentrating on definitions is that one rarely transcends rhetoric. So much debating time is spent about what something means in principle that one loses time considering what it signifies in

practice. It is suspected that the reluctance of many researchers to move beyond the definition stage is a symptom of their unwillingness to engage in the deeper and more challenging issues involved in applied tourism research. “Managing Heritage Tourism”

was a deliberate attempt to move beyond definitions and to look at the practice of sustainable tourism in the particular context of the heritage sector. Moreover our paper shows that definitions are not always helpful in conducting research. Imposing definitions on expert panellists would have served to hinder, rather than facilitate the Delphi process.

In qualitative research, the absence of precise definitions can often be a virtue rather than a vice.” In this context the limitations would have fallen on the practitioner respondents but the argument for an inclusive definition of urban tourism still holds.

The study of urban tourism development has for a long time been dominated by a concern for the planning of that development. This reflects the importance of the planning approaches in relation to both urban and rural spaces. In both development has been identified as a process that needs to be, and can be, planned and managed.

Tourism development

The need for planning tourism development can easily be justified by examples of unplanned development and their consequences. Planning is essential to achieve successful development as it can bring benefits without inducing significant problems and creating unwanted impacts (Gunn, 1994; Gunn with Var, 2002; Inskeep, 1994). As Gunn with Var (2002:3) observe: “The truth is that tourism development is being done by those who focus primarily on individual parts rather than tourism as a whole. Tourism can enrich people’s lives, can expand an economy, can be sensitive and protective of environments, and can be integrated into a community with minimum impact. But a new mind set is called for, that demands more and better planning and design of all tourism development, especially how the many parts fit together.”

Physical planning has taken place for centuries. Evidence of city planning can be found in several ancient civilisations (India, the Yukatan, etc.), and it was thriving in medieval

times, when walled cities were popular. In the UK, town planning has been practised since the 19th century. (Cherry, 1984) However, the social and economic elements of planning have been added to the process only in the 1970s. “Planning is a multidimensional activity and seeks to be integrative. It embraces social, economic, political, psychological, anthropological, and technological factors. It is concerned with the past, present and future.” (Rose, 1984:45)

Planning has not always been popular with people because of the negative connotations that had been attached to the term. What planning has been accused of - “planning places too much power in a governmental bureaucracy”, “elitism of professional planners”

(Gunn, 1994:19) - are features of conventional planning, a philosophy that puts planners as value-neutral experts in focus of the process, who determine what should be done, with hardly any consultation with those affected by the outcome (Lang, 1988)

A new planning philosophy emerged in the 1980s with the growing awareness of the importance of citizen input as an integral element of planning (Marshall, 1983; Lang, 1988). In the new concept, interactive planning, the emphasis has shifted from planning for to planning with, where public involvement is taken for granted. The plan is about what the participants of the planning process agree to do, and the whole process is based on continuous consultation and negotiation.

The underlying approach to tourism planning now is achieving sustainable development, a perspective that builds upon the merits of interactive planning whilst it includes new elements. This approach implies that “the natural, cultural and other resources of tourism are conserved for continuous use in the future, while still bringing benefits to the present society” (Inskeep, 1994:7)

Because of it multidimensional nature, “Planning is an extremely ambiguous and difficult word to define” (Hall, 2000:6). He argues that planning is only one part of an overall

‘planning-decision action’ process, where “various activities in that process may be difficult to isolate as the planning process and other activities involve such things as

bargaining and negotiation, compromise, coercion, values, choice and politics” (Hall, 2000:7). Both Hall and Gunn agree that planning embraces more than the production of plans, therefore a more holistic and integrative approach is needed to understand planning. This idea goes back to Murphy’s (1988) concept of planning which emphasises the need to anticipate and regulate changes in a system, and which is concerned to increase the social, economic, and environmental benefits of the development process.

Tourism planning has traditionally been associated with land-use zoning, with focus given to “site development, accommodation and building regulations, the density of tourist development, the presentation of cultural, historical and natural tourist features, and the provision of infrastructure including roads and sewage” (Hall, 2000:20).

However, with the rise of sustainable tourism development and the growing awareness of the wide-ranging impacts of tourism, the focus of planning started to shift from the purely economic aspect to the environmental and social-cultural aspects of tourism development. The four traditional categories of planning labelled as a.) ‘boosterism’, b.) economic industry-oriented approach, c.) physical/spatial approach and d.) community- oriented approach (Getz, 1986) started to lose their legitimacy and/or to merge into a sustainable approach to tourism planning. To understand the shortcomings of the four broad traditions, the basic characteristics of these need to be outlined.

‘Boosterism’ builds on the assumption that tourism is inherently good and it should be developed without giving any consideration to potential negative impacts. Cultural and natural resources are seen as exploitable assets, as potential tourist attractions, the tourism industry is considered as an expert who knows how to bring the maximum out of this potential using business terms for the development. Planning is primarily geared to boosting the volume of tourists to be attracted to the area, while the interest and concerns of the host community is completely neglected. Planners use forecasting as a method to define their growth targets and suggest a plethora of marketing activities, series of promotion and advertising campaigns to achieve the targets (Hall, 2000).

The economic approach to tourism planning builds on economic impact statements and advocates feasibility studies. Planning is primarily concerned with the potential economic benefits of tourism such as employment, foreign revenue, contribution to GDP, improved terms of trade, etc. In this case not the industry but the planner is considered an expert and development is defined in economic terms. Planning is based on the instrumental role of tourism as it is exploring ways of how it can be used as a growth pole, and how the positive impacts could be maximised. Planning literature uses multipliers to underline the necessity of development, classic methods include tourism master plans and some marketing initiatives such as market segmentation and schemes of incentives. (Gannon, 1994; Hall, 2000)

The physical/spatial approach regards tourism as a spatial and regional phenomenon thus development is defined mainly in environmental terms. As tourism is considered a heavy user of natural resources the potential negative environmental impacts are of primary concern. Key objectives of planning relate to environmental conservation and preservation of biodiversity, therefore planning aims to tackle the issues related to physical carrying capacity and suggest methods of visitor management. Typical examples of planning models include Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC), Recreational Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) or Tourism Opportunity Spectrum (TOS) (Gunn, 1994).

The community driven approach is hallmarked by the name of Peter Murphy (1985, 1988) who is acknowledged as the first academic in the tourism field to stress the importance of the local community in tourism development. He argues strongly for community control to ensure a balance between the needs and interests of the local community and those of the tourist and the tourism industry. Tourism development must be defined by socio-cultural terms, whereby the impacts of tourism that the community has to encounter are taken into consideration, which in turn will bring along positive changes in the local people’s attitudes towards tourism. This type of planning is also concerned about carrying capacity but the approach to the problem shifted from the environmental to the social perspective. Community driven planning is often associated with social impact assessment as well as community development through raising

awareness and education.

As it has been mentioned before, planning is an integrated process therefore none of the factors should enjoy special attention but rather the positive elements of the traditional approaches should be harmonised into a new approach to tourism planning (Hall, 2000;

Pearce, 2000, Burns, 2004). This new approach, besides the integration of economic, environmental and socio-cultural values, also recognises the political dimension of tourism. Planning therefore needs to address issues such as defining goals, objectives and priorities, achieving consensus between the needs of the local communities and tourism businesses as well as the policies of the public and the private sectors.

The next part of this chapter is going to discuss three approaches to tourism planning which are quoted most often in the tourism literature. The scope of the study does not allow for a more in-depth analysis of all the currently known tourism planning models, therefore the relevant works of Gunn (1994, and with Var, 2002), Inskeep (1994), and Burns (2004) are going to form the focus of the discussion.

There is an agreement among academics regarding the levels at which tourism planning is necessary. National, regional and local levels, and even site level (Gunn, 1994) are identified as the key levels in the planning process, however, there are debates as to which level of development should come first. Inskeep (1994) argues that national and regional development needs to precede planning at resort level. Gunn (1994) is sitting on the fence: in some cases he seems to be in favour of the bottom-up approach, according to which regional planning is essential to provide better integration of resources in the region, therefore to build a better relationship between the players at destination level and incorporate their plans into a tourism development plan at a larger scale. Nevertheless, when presenting the destination planning concept, Gunn argues that development at destinations (and also at site scale) needs to be a follow-up to regional planning.

Another contradiction that underpins Gunn’s approach to planning is the inconsistency in the identification of the players that are or should be part of the planning and

development process. On the one hand, he keeps referring to the governments, the non- profit organisations and the commercial enterprises as the major players in tourism development; the local communities are very often excluded from it. On the other hand, he recognises the importance of the local community: “It is in and around communities that tourism development can and will succeed.” (Gunn, 1994:225) Therefore, he suggests that the local communities be involved in the destination planning process.

No development takes place without a purpose. Gunn (1994) identifies four major goals that underpin tourism planning:

Enhanced visitor satisfaction - developers must understand and consider the needs of tourists in order to be able to provide the right range and quality of services

Improved economy and business success - improved economy is in most cases the primary reason for tourism development

Protected resource assets - a new goal for tourism development is to commit to resource protection, otherwise tourism businesses and bodies developing tourism will lose the attraction to promote

Community and area integration - tourism must be integrated into the social and economic life of the community as it involves the destination’s public and private bodies and segments of the public (1994:16)

Sustainable planning emphasises the importance of community involvement as a key success factor of successful tourism development. Although Inskeep (1994) also argues for community-based tourism planning, his suggested way of involving the community still leaves a lot to be desired. He suggests that at the national and regional levels of planning, a steering committee is appointed, which is composed of the representatives of the relevant public sector bodies, the private sector, the community and other relevant organisations (he does not go into detail about the nature of these organisations).

However, Inskeep does not elaborate what he means as community in the case of national and regional tourism plans. “Also, open public hearings can be held on the plan. These hearings provide the opportunity for anybody to learn about the plan and express their opinions. Another common approach, when the plan is completed, is to organize a

national or regional tourism seminar. This meeting informs participants and the general public about the importance of controlled tourism development and the recommendations of the plan.” (Inskeep, 1994:9-10)

It seems that Inskeep finds it sufficient to tell the community about the plans, rather than letting the community express their ideas, therefore providing opportunity for real involvement instead of a token gesture. He believes that the ‘bottom-up’ approach is

“more time consuming and may lead to conflicting objectives, policies and development recommendations among the local areas” (1994:10)

Phases of tourism planning

Gunn (1994) suggests that the planning process start with addressing specific issues that he calls planning antecedents. These issues include:

Early implementation considerations - integrating implementation at the outset rather than adopting the traditional plan, implements approach

Impact considerations - mostly referring to environmental impacts, but emphasising the need to involve all the affected parties from the start to get a better understanding of possible impacts

Communication/Education - fundamentals of tourism need to be communicated to the various bodies and individuals involved (through public meetings, seminars, workshops, reports, journals, etc.)

Promotional ethics - avoiding exaggerated claims and presenting the truth about both the benefits and costs of tourism development

Policy - many nations have introduced policies regarding freedom-of-travel, immigration, but issues as “lessening the tension between countries of contrasting ideologies”, tension between wealthy and poor nations” (Gunn, 1994:113) influence tourism policies

Co-operation/Collaboration - “tourism planning must be integrated with all other planning activities” (Gunn: 1994:114)

Once these antecedents are considered, the actual planning process can go ahead. Gunn suggests that planning at different levels may take different forms. The planning concept Gunn devised for regional levels is referred to as supply side planning as it focuses on the supply elements of tourism. The key steps of regional tourism plans are outlined in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Key steps of regional tourism planning (Gunn (1994:142)

The 5-step process acknowledges the importance of research, and leaves room for feedback and consultation during the middle phases of the process; however, it does not allow for the revision of planning objectives during the process. Gunn suggests that the supply side plan should be accompanied by a continuous planning action “which could be modelled as an interactive system whereby each sector is not subjected to a superior level of planning. Instead, each sector on its own initiative interacts with all others in its own decision making.” (Gunn, 1994:146) The examples provided for continuous action planning however, do not highlight the significance of this type of planning in assisting regional tourism plans.

Gunn does not devise a similar development plan for destination level, he draws on the

experience of Canadian and American destination developments. He quotes Weaver (1991) who suggests the following steps be considered:

1. Inventory and describe the social, political, physical and economic development.

2. Forecast or project trends for future development.

3. Set goals and objectives.

4. Study alternative plans to action to reach goals and objectives.

5. Select preferred alternative(s) to serve as a guide for recommending action strategies.

6. Develop an implementation strategy.

7. Implement the plan.

8. Evaluate the plan.

(Weaver, 1991:28- 29)

Similar critique to Gunn’s regional planning concept can be expressed here as well:

evaluation is regarded only as a last step in the development process, and this does not allow for monitoring at all.

Gunn also implies that Steiner’s (1991) organic/rational planning process can be applied to tourism planning, in combination with ‘destination continuous planning’ and community planning. Steiner’s model is much more flexible in that respect that it leaves space for continuous feedback.

Figure 2.2 Continuous planning (Steiner, 1991 in Gunn, 1994:256)

Continuous planning in case of a destination involves the establishment and work of an organisation that monitors and evaluates the tourism development plan on a regular basis, and integrates in with the plans of higher levels. Another crucial task of this organisation involves co-operation with the three sectors Gunn identified earlier (governments, non- profit organisations, commercial enterprise), and with regional tourism planners, managers, and policy-makers.

Gunn suggests that tourism planning is integrated into community planning, especially emphasising the critical role communities play in destinations. As he says, community plans traditionally focus on the physical public needs, but do not recognise the overlap between the needs of visitors/tourists and residents, therefore ignore issues of tourism.

Inskeep (1994) adopts a comprehensive approach to tourism planning, which allows for considering all the elements of the tourism system in the planning and development process. He also suggests that the integration of tourism into the overall development policies of a country, region or destination is essential, as tourism overlaps several different sectors of the society and economy.

The most important merit Inskeep must be credited with lies in his recognition of the

importance of continuity and flexibility in tourism planning. He suggests that planning needs to be flexible to allow for adapting to changing circumstances. However, the tourism planning process that he outlines seems to be a step-by-step process:

Study preparation

Determination of objectives

Survey of all elements

Analysis and synthesis

Policy and plan formulation

Formulation of other recommendations

Implementing and monitoring

Figure 2.3: The tourism planning process (Source: Inskeep: 1994:12)

He emphasises the importance of careful study preparation, where the terms of reference are formulated. The terms of reference (the outputs and activities that are necessary for the development of the plan) must be formulated in a way that allows the plan to achieve the desired results. As the notion of planning changes, the terms tourism development and planning are more and more often used interchangeably, however it must be noted that even in the 21st century tourism development takes place without planning.

Implementing plans is far more difficult and complicated than one could expect. For one reason, plans are supposed to include a plethora of decisions made by public bodies, businesses and individuals, and the number of decision-makers involved suggests that opposing interests may emerge.

Tourism inevitably has an impact on the natural, economic and socio-cultural environment, both in rural and urban areas. The positive impacts are generally acknowledged, but the real emphasis is on the negative impacts of tourism in most studies, as they very often outweigh the positives. However, it is difficult to assess which problems can be blamed on tourism because “In many tourism destinations public use has existed for long periods of time so that it is now almost impossible to reconstruct the environment minus the effects induced by tourism.” (Mathieson and Wall 1982:5)