Patrik TátraiA, Ágnes ErőssA, Monika M VáradiB

A Geographical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, 1112 Budapest, Budaörsi út 45;.

tatrai.patrik@csfk.mta.hu; eross.agnes@csfk.mta.hu

B Institute for Regional Studies, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, 1097 Budapest, Tóth Kálmán utca 4; varadim@rkk.hu

Abstract

Educational migration is considered to be one of the most significant types in the migration from Serbia to Hungary. During the last thirty years, many Hungarian families in Vojvodina have come to the deci- sion that after finishing primary school in Serbia, their children should pursue their secondary and ter- tiary studies in Hungary. Szeged is one of the main destinations of this type of migration, while at the same time it is also home to the most populous Vojvodinian community and serves as a scene for di- verse, intensive cross-border activities. Based on narrative and structured interviews – conducted with Vojvodinian students living and studying in Szeged and also with heads of educational institutions – our main interest was to reveal how the direction and dynamics of cross-border migration and individu- al (or family) migratory decisions are challenged on the one hand by Hungary’s kin-state policy regard- ing Hungarians outside Hungary and by the educational regulations of the Hungarian government and its institutions.

Keywords: Cross-border educational migration, kin-state politics, migration decisions, transnational- ism, Hungarian minority in Vojvodina

CROSS-BORDER EDUCATIONAL MIGRATION FUELLED BY HUNGARY’S KIN-STATE POLITICS IN THE SERBIAN-HUNGARIAN BORDER ZONE

Introduction: Cross-border transnational migration and ethnicity

1 Entitled Integrating (trans)national migrants in transition states, the project has been headed by Doris Wastl-Walter and funded by the SCOPES program of the Swiss National Science Foundation (www.transmig.unibe.ch).

Educational migration is considered to be one of the most significant types in the migration from Serbia to Hungary. During the last thirty years, many Hungar- ian families in Vojvodina have come to the decision that after finishing primary school in Serbia, their children should pursue their secondary and tertiary studies in Hungary. Szeged is one of the main desti- nations of this type of migration, while at the same time it is also home to the most populous Vojvodini- an community and serves as a scene for diverse, inten- sive cross-border activities.

The present study is an empirical analysis of the features of educational migration across the Serbian- Hungarian border in the context of an international

research project.1 Based on narrative and structured interviews – conducted with Vojvodinian students at- tending secondary or tertiary education in Szeged and also with heads of secondary-education institutions between 2010 and 2012 – our main interest was to re- veal how the direction and dynamics of cross-border migration and individual (or family) migratory deci- sions are challenged on the one hand by Hungary’s kin-state policy and by the educational regulations of the Hungarian government and its institutions.

Cross-border educational migration is a form of transnational migration, which, in its broadest sense, can be seen as migration across political and na- tional borders (Jordan & Düvell 2003). “We define

Demographic Development, Population Policy and Migration

‘transnationalism’ as the processes by which immi- grants forge and sustain multi-stranded social rela- tions that link together their societies of origin and settlement. We call these processes transnationalism to emphasize that many immigrants today build so- cial fields that cross geographic, cultural, and politi- cal borders. Immigrants who develop and maintain multiple relationships – familial, economic, social, organizational, religious, and political – that span borders we call ‘transmigrants’. As essential element of transnationalism is the multiplicity of involve- ments that transmigrants’ sustain in both home and host societies.” (Basch et al. 1994: 7). Transnational- ism is neither a permanent state nor a constant event, but rather a process; the intensity and frequency of transnational relations can vary, just as the ways in which transmigrants may be linked to their coun- try of origin vary. However, being transnation- al does not necessarily mean possessing a transna- tional identity or a sense of transnationality (Levitt

& Glick Schiller 2004). We furthermore use the con- cepts ‘transnational society’ and ‘transnational so- cial space’ (Faist 2016) because they challenge pre- conceptions about closed nation-states. Feischmidt and Zakariás (2010: 159) define transnational soci- eties as “societies that exist and function regardless of geographical factors.” What one sees is not a sin- gle, one-way migration between locations, but mul- tiple to-and-fro movements, and migrants typically remain open to further movement in the future. In our case, Vojvodinian students who study at second- ary schools or universities in Hungary are transmi- grants who simultaneously live in two countries and whose relations link them to two countries, albeit in different ways and with different intensities. The in- dividual perspectives on and the outcomes of trans- national educational migration can also be consid- ered open: it can lead to the migrant permanently settling in Hungary, permanently or temporari- ly moving back home to Vojvodina, or even moving on to a third country (Szentannai 2001). The specific form of transnational educational migration we ex- amine is that in which migrants who are members of the transborder Hungarian minority move to a

country which many of them consider their moth- er country, and although they are separated from the country by the national borders and the Schengen Agreement, there is no cultural or language barri- er. It is because of this characteristic that some au- thors categorize migration from the surrounding countries to Hungary as something in between in- ternal migration and international migration, estab- lishing a category of its own in which, when exam- ining the migratory process, the common historical roots, ethnic identity, cultural similarities and com- mon language must be considered (Gödri 2005: 79).

The theory of transnational migration is connected to the concept of the deterritorialized nation, a con- cept which is important for two reasons. In gener- al, it means that transmigrants, through their activ- ities, can belong to two or more nations at the same time without being physically present in a given state, that is to say, without living within the borders of the given state. In the specific Hungarian context, it must be emphasised that the decisions and discourses con- cerning Hungary’s kin-state politics all aim at creat- ing a common deterritorialized nation, to which all Hungarians belong, regardless of where they might live. This is the new form of transnational policy Mi- chael Stewart writes about, and this is what he means by describing transborder Hungarians as ‘developing transnational minorities’ (Stewart 2003). In the last few years, the deterritorialized Hungarian nation ex- isted only in a symbolic and cultural sense; however, the amendment of the Hungarian Citizenship Law re- sulted in a simplified naturalisation procedure com- ing into force in January 2011. This made it possible for people living in the former territory of the King- dom of Hungary to acquire Hungarian citizenship without residing in Hungary. Anybody is eligible for preferential (re)naturalisation who or whose ances- tors held Hungarian citizenship once, and who proves his/her knowledge of the Hungarian language. This law served both symbolic goals like the re-emerging nation-building project (“national reunification”, Po- gonyi 2015), and pragmatic goals such as to expand the governing Fidesz’s voter base with new non-resi- dent citizenship.

Dilemmas in immigration and kin-state politics

One of the features of migration to Hungary is that two-thirds of the people coming to and settling in the country is from the Hungarian communities of the surrounding states (Tóth 2003). It is because of this feature that Hungarian immigration policy, which is often considered merely an ad hoc solution by its

critics, is closely intertwined with the equally im- mature kin-state politics (see e.g.: Çağlar & Gereöffy 2008; Feischmidt & Zakariás 2010; Waterbury 2010).

Ever since the regime change of 1989, the basic prin- ciple of Hungary’s kin-state politics has been to help Hungarians outside the borders thrive in their native

country;2 in other words, the goal has been to main- tain a Hungarian presence throughout the Carpathi- an basin. However, this priority is in opposition to po- litical, economic and social interests. For example, it is also very important to maintain good relationships with the neighbouring countries, which are extreme- ly sensitive to Hungarian political discourses and de- cisions concerning the Hungarian minorities that live within their borders. One of the most important facts in connection with migration is that, due to the ag- ing and decline of Hungary’s population, the country needs a new labour force (Blaskó & Fazekas 2016), and the simplest way of increasing the size of the active population while causing as few conflicts as possible and costing society the least amount is to have Hun- garians living outside Hungary migrate to the country.

At the same time, ethnic kins are considered to be an asset as well if remaining in their homeland, because Hungary’s kin-state politics can rely on them to fulfil Hungary’s regional economic and geopolitical goals (Tátrai et al. 2017).

This calls attention to the (long-standing) conflict of interest of Hungary’s kin-state politics: whether to help transborder Hungarian communities to stay in their homeland or enhance their migration to Hun- gary to satisfy the country’s demographic and labour needs. Since the political transformations in 1989, all political forces in Hungary have explicitly supported the first goal; however, some of the measures imple- mented implicitly served the second aim. The amend- ment of the Hungarian Citizenship Law reflects such controversies: however, it does not support directly ethnic kin’s migration to Hungary but still facilitates it. Nevertheless, kin-state politics lacking a clear, co- herent, one-way road, they serve both aforementioned directions instead. As Çağlar and Gereöffy (2008: 333) noted “it is the controversies in Hungarian diaspo- ra politics which impeded the development and the implementation of a comprehensive migration poli- cy in Hungary.” Contemporary kin-state politics are not without such controversies although they clearly communicate welfare in the homeland as a final goal together with collective rights and autonomy, which reflects that nowadays the balance between migrato- ry and diaspora (ethnic) politics shifted towards the first one, primarily as a consequence of the extension of the Hungarian citizenship.

2 This principle can be found in the 1989 constitution as well as in the 2011 basic law (Article D): “Motivated by the ideal of a unified Hun- garian nation, Hungary shall bear a sense of responsibility for the destiny of Hungarians living outside her its borders, shall promote their survival and development, and will continue to support their efforts to preserve their Hungarian culture and foster their cooper- ation with each other and with Hungary.”

3 In practice this means preferential (re-)naturalization of Hungarians outside Hungary, which, since 1 January 2011, can be requested without a place of residence in Hungary.

Not only the ‘focus’ but the targets and instru- ments of kin-state politics are controversial as well, because the policy simultaneously seeks to support the creation of a deterritorialized (culturally and po- litically) unified Hungarian nation and to secure col- lective minority rights for transborder minority com- munities and help them achieve autonomy. Complete (economic, cultural, political, and territorial) auton- omy in the neighbouring countries does not appear to be an achievable alternative today for many rea- sons, such as the assimilation policies of neighbour- ing nation-states and the dwindling and internal po- litical division of minority communities. With regard to Vojvodina in Serbia, the site of our research, where the percentage of the largest (Hungarian) ethnic mi- nority is 13% of the total population according to the last census held in 2011, the province is politically and administratively but not economically autonomous.

The second goal of Hungary’s kin-state politics, the virtual “reunification” of the Hungarian nation, can be quickly and easily achieved with the institution of dual citizenship,3 which was introduced in 2010.

Naturally, professional and political views about Hungary’s kin-state politics vary in Hungary. Dur- ing the debate about dual citizenship it was none oth- er than a Vojvodinian constitutional lawyer who, rep- resenting one of the strongest critical standpoints, pointed out the inconsistencies among the policy tar- gets and instruments mentioned above: “…there is an irresolvable conceptual contradiction in that Hungar- ian communities outside Hungary would like to ac- quire the status of partner nation, to achieve a degree of autonomy that would require the modification of the nation-state model, and at the same time, to de- mand Hungarian citizenship on the grounds of eth- nically belonging to the nation-state.” (Korhecz 2010:

167). As in Hungary, priority is given to discourses about kin-state politics and there is no opportunity to start a political or public debate about the politi- cal, demographic and economic reasons for and con- sequences of substantial ethnic migration to Hungary from neighbouring countries or about a desirable im- migration policy (Feischmidt & Zakariás 2010: 156).

Nor is there any ongoing dialogue about whether the instruments and decisions of kin-state politics are able to influence the readiness of Hungarian commu- nities beyond the border of Hungary to migrate, and if they are, then to what degree and in what direction?

Cross-border educational migration influenced by kin-state politics

4 This figure does not only reflect students who receive a scholarship, because, compared to the total number of students who come to study in Hungary, their number is dropping (Szentannai 2001); most students paid tuition for their university education during the 2000s and since the introduction of preferential (re)naturalization, most of the transborder Hungarians participate in Hungarian ed- ucation system for free as Hungarian citizens.

5 Off the fathers of students studying in Hungary, 22.6% have a university degree or diploma, whereas the same rate for fathers of stu- dents studying at Serbian universities is only 7.7% (IDKM 2010).

For our research, the most important element of kin- state politics is the support it gives to Hungarian stu- dents studying in Hungary but coming from outside the country (for further details, see Erdei 2005; Epare 2008;

Molnár 2008; Takács et al. 2013). A feature of the system that was introduced in the early 1990s is that communi- ties outside Hungary can form scholarship boards and, taking the needs of the specific community into consid- eration, each board can decide which student may study what subject at Hungarian higher education institutions and receive a scholarship from the Hungarian state. Part of the support system is a network of student hostels, named Márton Áron Special College Network, that ca- ter for students’ needs (see Márkus 2014). The so-called specialist student hostels first welcomed students in Bu- dapest, and then, after the turn of the century, in eve- ry important university centre throughout the country.

The practices and philosophy at the Márton Áron Spe- cial College Network are aimed at providing education to Hungarian intellectuals living outside Hungary, re- inforcing their identities and helping them return home.

The special college establishes a social space in which mainly Hungarian transborder students live together and are linked in their free time as well by the numerous services provided.

From the beginning, the stated goal of the schol- arship system was to reinforce the ranks of Hungari- an transborder intellectuals, but it quickly became ob- vious that most of the students studying in Hungary do not wish to return to their native country. That is why at the turn of the century during a reform to the scholarship system, regulations were implemented ac- cording to which students taking part in the program were obliged by contract to return to their home coun- try once their studies were over. However, this reform failed to reduce the levels of migration, just as the con- tinuous cuts to the state scholarship budget and the support provided for the establishment of Hungarian higher education institutions outside Hungary (main- ly in Romania and Slovakia) have failed. A signifi- cant proportion of students studying in Hungary, es- timated as about 50 to 70% (Gödri 2005: 88; Szügyi &

Takács 2011: 296), never return to their native coun- try.4 The head of the Márton Áron Student Hostel in Szeged points out: it has never happened that a stu- dent who did not return to his/her country had to re-

pay the scholarship because the state does not moni- tor whether the conditions of the contract have been fulfilled. This means that the political instruments, which were supposed to provide education for trans- border Hungarian intellectuals, have been success- ful only to a limited extent in achieving their original goals of keeping intellectuals in their native country.

Furthermore, they did not have any significant influ- ence on the migratory decisions of young people, ex- cept for encouraging educational migratory decisions by providing scholarships.

The parents of young Vojvodinian Hungarians un- dertaking educational migration possess above aver- age qualifications (Erdei 2005). According to surveys, the parents of Vojvodinian university students study- ing in Hungary have a much higher educational level, than the parents of those who go to a Serbian universi- ty.5 There is also a remarkable difference in the quali- fications acquired prior to entering tertiary education:

while two-thirds of the students studying in Hunga- ry were educated in a secondary grammar school, the rate is reversed in the case of university students in Serbia, in which two-thirds have a vocational educa- tion, meaning they attended a secondary-education institution of lower prestige. These results give rise to the hypothesis that can only be confirmed through personal experience and not by systematic research, namely, that “members of the Hungarian elite in Vo- jvodina educate their children in Hungary” (IDKM 2010). Thus, it could be said that the elite of the Vo- jvodinian minority is characterized by a transmigrant lifestyle. The research mentioned above also points out that the level of migratory intentions is constant- ly high; the rate of potential migrants among students in Serbia is 70%, whereas among students studying in Hungary, it is 90% (IDKM 2010).

With these figures in mind, it is no surprise that studies on the educational opportunities and migra- tory readiness of young people are, especially when conducted by researchers of Vojvodinian origins, partly inspired by advancing ethnic and minority policy concerns. They are concerned that the contin- ual migration especially of highly qualified intellec- tuals might endanger the survival of Hungarian mi- nority communities in Vojvodina (e.g.: Mirnics 2001;

Gábrity 2002, 2007; Fercsik 2008; IDKM 2010; Takács

et al. 2013; Takács & Gábrity 2014; Palusek & Trombi- tás 2017; Kincses & Nagy 2019).6 From a Vojvodinian point of view, one of the main reasons for education- al migration could be that there is no local, independ- ent Hungarian higher education and that, especially

6 In the years after 2000, 20–25% of Vojvodina’s Hungarian college and university students were involved in higher-education migration to Hungary. The number increased to 30–35% by the beginning of the 2010s (Szügyi & Takács 2011).

7 At some colleges in Subotica and at some faculties at the University of Novi Sad, in fact, there is partial or complete education in Hun- garian. Also, in sister departments at Hungarian institutions, it is possible to acquire a degree in horticulture and information tech- nology. A comprehensive overview of secondary and tertiary education services in Vojvodina would be too extensive for the present study, so for more details on the topic, see Gábrity 2002 and Takács & Gábrity 2014.

8 In our study, the adjective ‘Serbian’ refers to migrants arriving from (ex-)Yugoslavia, Serbia and Montenegro and the Republic of Ser- bia. Official statistics do not include students’ ethnicity and place of residence, yet 80-90% of the educational migrants coming from the successor states of Yugoslavia speak Hungarian as their native language, are of Hungarian descent, and live in Vojvodina.

9 Hungary’s accession to the EU also contributed to the changes in educational migration. Due to legal harmonization within the EU, the same laws apply to students who are Serbian citizens as to citizens of other third (non-EU) countries. Thus, after the 2007 amend- ment of the public education law, children may only receive free compulsory education if their parents can certify that they have in- come and housing in Hungary. Earlier, by law, the Hungarian state funded their education as well.

10 The study by Kincses and Nagy (2019: 225) proved that correlation between the attraction zone of University of Szeged in Vojvodina and the territorial distribution of ethnic Hungarians in Vojvodina is quite strong (0.851).

at university level, the existing network of institutions offers neither sufficiently diverse departments, nor satisfactory opportunities for students to study in their native language.7

Educational transnational migration at the Hungarian-Serbian border

In the 1990s, when the country’s borders were opened, a high number of young transborder Hungarians ap- peared in the Hungarian public and higher-education systems. Romania and Slovakia provide the highest number of migrants, closely followed by the former Yugoslavia. For over a decade, the number of Serbi-

an8 students studying in Hungary was mainly influ- enced by the fluctuation of the Yugoslav Wars, and their number in Hungarian institutions of secondary and tertiary education sharply increased at the time of the NATO bombings. In general, it can be said, that while the demand for tertiary education has remained constant during the 2000s, the number of students at- tending secondary education has been steadily drop- ping in this period (Table 1). One of the main reasons behind this is the process of democratization in Ser- bia: some aspects of Vojvodinian autonomy, including education, have been restored and secondary schools have been established for talented children where the language of education is Hungarian.9 Beyond the in- stitutional reasons, the general demographic char- acteristics of Vojvodian Hungarians, namely the low birth rate and emigration, resulted in population age- ing, have also contributed to this situation through- out the period under review (see e.g. Milanović 2006;

Živković et al. 2008; Badis 2012).

However, after 2010, when preferential (re)natural- ization came into effect, both the number of pupils in public education and students in higher education has grown. The widely acquired non-residential Hun- garian citizenship made Hungarian education tuition free for passport holders and facilitated the intensi- ty of connections between the two sides of the border

(Kincses & Nagy 2019). While number of pupils with Serbian (or with dual) citizenship has only increased by 30 percent, number of students in higher education doubled between 2008 and 2018 (Table 1).

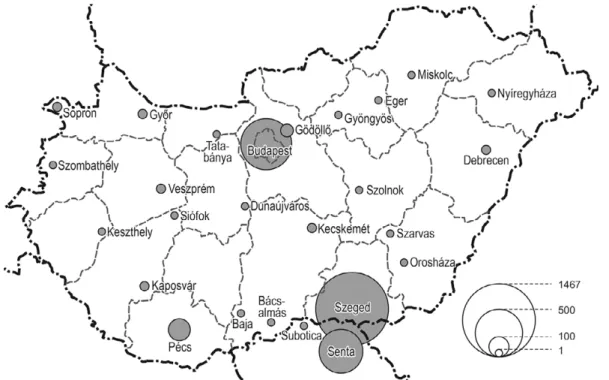

Most of the Serbian students studying in Hungary are concentrated in the region we examined, in the city of Szeged in Csongrád County (Figure 1). According to a 2005 analysis conducted by the Hungarian Ministry of Education, 61% of the students from Serbia and Mon- tenegro in Hungarian public education studied at pri- mary and secondary schools in Csongrád County, 13%

studied in Budapest and 11% at institutions in Bács- Kiskun County, as it is closer to Vojvodina, making transportation easier (Kováts & Medjesi 2005). Accord- ing to a 2010 study, 62% of Serbian college and universi- ty students in Hungary are educated in Szeged, and 1 in every 4 is a student at an institution in Budapest (Dan- ka 2010). The research by Kincses and Nagy (2019) con- firmed, that spatial patterns have not changed signif- icantly in the last years: in the 2017/2018 school year, 58% of the Serbian citizens studying in Hungary at- tends higher education institutions in Szeged.

There are two reasons for this phenomenon: first, the educational services provided by the city are of high quality. Second, most of the students with Serbian cit- izenship reside in North Vojvodina, where majority of ethnic Hungarians live (Figure 2).10 Since Szeged is the closest city to the border, only few kilometres far from Hungarian settlements in North Vojvodina, education- al migration influenced by geographical proximity. In this case, one can interpret such cross-border mobili- ty as connection between city and its attraction zone – which otherwise extends beyond the border.

Table 1. The number of Serbian citizens in kindergarten and primary, secondary and tertiary education in Hungary School year Kindergarten Primary school Vocational school Secondary general

school College/

University

1995/1996 .. 376 92 572 596

1996/1997 .. 339 92 540 ..

1997/1998 .. 308 89 488 ..

1998/1999 .. 295 73 499 281

1999/2000 .. 395 84 676 843

2001/2002 55 306 49 634 822

2002/2003 65 307 80 556 796

2003/2004 30 282 73 511 663

2004/2005 29 222 72 509 714

2005/2006 33 232 71 465 755

2006/2007 35 194 101 485 765

2007/2008 35 170 81 421 871

2008/2009 38 139 47 380 868

2009/2010 39 211 71 401 1009

2010/2011 38 174 60 353 1136

2011/2012 52 220 40 359 1244

2012/2013 52 200 32 427 1465

2013/2014 49 198 26 417 1543

2014/2015 57 208 30 483 1321

2015/2016 76 197 25 486 1670

2016/2017 61 204 46 524 1632

2017/2018 73 202 59 543 1761

2018/2019 36 111 22 319 1767

Source: Statistical Yearbook of Public Education 2018/2019, Budapest, 2020: 38

Figure 1. Serbian citizens applying in the Hungarian higher education, according to the place of education, 2005–2010 Source: Takács et al. 2013: 8.

Migration in secondary education

During the 1990s, cross-border educational migra- tion became closely intertwined with the migration of families fleeing the country due to the crisis brought about by the Yugoslav Wars, military drafts, growing poverty and untenable standards of living. The mi- grants arriving in Szeged at the time lived in uncer- tainty and fear and, for a long time, they clung to the hope that the war would soon end and they could re- turn home. On both sides of the border, myriads of families and children, often separated from each oth- er, lived under circumstances they thought of as tran- sitory. In 1993 still, a study found that many were liv- ing under temporary, migratory circumstances. It also found that Vojvodinian children studying in Sze- ged were talented, achieved good results, had favour- able family backgrounds and that many of their par- ents, some of whom were well-to-do businessmen with developing business interests in Hungary, were highly qualified (Imre 1993: 22).

When we enquired about cross-border education- al migration at institutions of public education in Sze- ged, we found that during the last two decades the presence of Vojvodinian students became fairly com-

mon and these students did not stand out in any way from other students. However, as in the 1990s, chil- dren and their families still often lived under tem- porary, transitional, and migratory circumstances.

Most children with parents in Vojvodina live in stu- dent hostels or flats, but some parents buy a flat for their children in Szeged as preparation for the child’s or the entire family’s permanent relocation to Hunga- ry. Many of the Vojvodinian students’ parents have a sustainable livelihood in Hungary, so even if they do live in Vojvodina, they still have ties to both countries and seek to plant roots in Hungary, if for no other rea- son than to secure the future of their children.

When, in 2007, the legislative changes came into force, the local government of Szeged issued a regu- lation which made it possible for heads of education- al institutions to exempt Vojvodinian students from paying tuition or to reduce it by taking the students’

social circumstances or academic achievements into consideration. What also points to the special status of transborder Hungarian students is that the regu- lation only affected them and not students from oth- er third countries, like the children of Chinese fami- Figure 2. People from Vojvodina applying for studies in Hungarian higher education,

according to their place of residence, 2005–2010 Source: Takács et al. 2013: 10.

lies living in Szeged and of compulsory school age. In the last decade, the opportunity to apply for Hungari- an citizenship led to an increase in the number of Vo- jvodinian Hungarians in secondary schools in Szeged, because, as Hungarian citizens, they have the same rights as their Hungarian peers, including the right to free public education. But even though hardly any students have to pay a full tuition fee, for many fami- lies, educating their children in Hungary still means a great financial burden.

In the cross-border market of educational servic- es, secondary schools in Szeged mean competition for Hungarian–speaking secondary schools in Vojvodina.

The institutions on the Hungarian side of the border enjoy an advantage for many reasons. As a regional

11 In the survey conducted with Hungarian university students from Vojvodina, the researchers were also curious about the motivation behind the readiness to migrate. Of the students interviewed, 82.8% responded that they would leave the country where they were born in hopes of making a better living somewhere else, whereas only 6.6% said they would leave due to their disadvantageous minority status (IDKM 2010).

educational centre, Szeged can offer a broader range of educational services than Vojvodinian secondary schools. It further adds to their advantage that pupils who wish to go to a Hungarian college or universi- ty believe that a baccalaureate from a Hungarian sec- ondary school will make it easier for them to enter ter- tiary education. All this means that the decision to go to a secondary school in Hungary fits into a long-term, migration and mobility strategy for both an individ- ual and the family. The influence of Szeged’s second- ary schools mainly extends to settlements close to the border. Vojvodinian children sometimes live closer to Szeged than many of their peers from Hungarian vil- lages, and they regularly go home to their parents and friends beyond the border for the weekend.

Special features of transnational educational migration

According to interviews with young Hungarians from Vojvodina, the main driving forces behind ed- ucation migration to Hungary are the following: the most important of the factors pushing for migra- tion was the complete lack of or limited access to education in the native language, while converse- ly the most important factor pulling toward migra- tion proved to be Szeged’s wide range and high qual- ity of educational services. Language skills also play a major role in migratory decisions (Gábrity 2007;

Kincses & Nagy 2019). For example, children from homogeneous Hungarian communities, encounter a particularly serious problem in that they lack com- mand of the Serbian language. Serbian is only taught as it was their mother tongue and often our inter- viewees proved to be sceptical about the quality of language teaching. The inadequate knowledge of the state language in itself may be sufficient to fuel the educational migration process to Hungary.

However, apart from the basic desire for education in one’s native language, migratory decisions are also partially determined by prospects of a better liveli- hood, and these needs grow stronger during the years of education. A case in point is that higher education in Serbia is not even attractive for those who grew up in a mixed ethnic environment and have good com- mand of the state language. Hungary offers a higher standard of living and greater employment opportu- nity than Serbia. It should also be recalled that since accession to the EU in 2004, Hungarian diplomas are recognized throughout the entire EU labour market, while Serbia is still waiting for accession.

Though the ethnicity of young Hungarians from Vojvodina serves as a cultural and social capital for their migration to Hungary, this process is deter- mined by economic factors as well as by ethnic factors (Gödri 2004). Migrants’ accounts often reveal that ethnic and economic motives are linked and that to- gether, they influence the migratory decision. During the interviews, ethnic dimensions appeared primari- ly in a positive context: interviewees expressed a nat- ural, sometimes unconscious, connection to Hunga- ry and an appreciation that the language and culture are the same. Very rarely did young people and stu- dents mention the drawbacks of belonging to a trans- border minority, and even when they did, it mainly concerned the limited access to career opportunities (a problem related to the lack of language skills).11

By conducting interviews with Vojvodinian stu- dents who previously studied or are currently studying in Hungary, we gained a number of insights: that trans- national migration may best be described as a process (Levitt & Glick Schiller 2004); that permanent resettle- ment takes place gradually (Salt 2001); and that a mi- grant often tries to gain a foothold in both countries to see where the chances of an adequate livelihood are better. We also realized that transmigrant moving back and forth across the border is not characterized by a spirit of entrepreneurship or particular open-minded- ness. Many young people consider that their future is open and that their current residence and circumstanc- es are not permanent, so a final decision as to where to live is commonly drawn out. However, while livelihood and career prospects have a great impact on the final

(re-)settlement decision, social relations, such as mar- riage and family planning, also have a decisive influ- ence on the outcome of the migratory process.

The importance of social networks in the migratory process can be seen in many ways in individual lives (Tilly 1991; Massey et al. 1993; Gödri 2004). Without a family’s active support, a child would not be able to decide to pursue further studies. However, an envi- ronment that accepts and supports migration needs to be wider than just the family: teachers must inform students about the possibility of transborder educa- tion; parents and students visiting home need to hand on information to each other about schools; and then

12 The importance of social networks is indicated, for example by the fact that in 2010, 35.6% of Vojvodinian Hungarians studying at Hungarian universities had family members studying abroad, while the same figure for Hungarians studying in Serbia is only 9.4%

(IDKM 2010).

these pieces of information can promote and confirm individual and family migratory decisions. When making such decisions, migrants rely heavily not only on a supportive environment at home but also on sib- lings, relatives, friends and peers who have already re- settled. These relationships help to mitigate the risks and losses of migration and provide models as well.

Thus social networks at home and in the target area of migration become a source of strength. They con- tribute to making migration a legitimate, individual and collective life strategy spanning across genera- tions, and so they themselves become factors that sus- tain and fuel migration.12

Conclusions

The three-decade-old transnational educational mi- gration at the Hungarian-Serbian border is a process determined by both ethnic and economic factors, and concerns primarily minority communities with Hun- garian language and identity on the Serbian side of the border. For this reason, Hungary’s kin-state pol- itics, and its related educational policy attempt to in- fluence the nature and extent of this form of migra- tion. Though our field research was carried out several years ago, it showed, what our current data analysis and other recent researches have also confirmed, that this policy, with its associated instruments, is unable to fulfil its most important purpose, which is to safe- guard the existence of an intellectual elite in Hungar- ian minority communities and to help them sustain a livelihood in their native country.

However, what proved to prevail were the push and pull factors and transmigrant networks, which not only amplify educational migration but make it a sup- ported, legitimate individual and family strategy as well. This form of transnational migration is charac- terised by migrants being linked to two worlds simul- taneously, though the connection differs according to individual circumstances and its intensity changes over time. Although the outcome of such transnation- al migration is considered to be open, our research in- dicates that, in the majority of the cases, it is the first step towards permanently leaving behind the native country. Thus strategies and decisions concerning a child’s education are at the same time long-term mi- gratory decisions and strategies.

References

Badis, R. (2012): Látlelet a vajdasági magyarok de- mográiai helyzetéről [The demographic situation of Hungarians in Vojvodina]. Pro minoritate, 16(3), 27–38.

Basch, L., Glick Schiller, N., & Szanton Blanc, C.

(1994). Nations Unbound, Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. London and New York: Routledge.

Blaskó, Z. & Fazekas, K. (eds., 2016). Munkaerőpiaci tükör [Report on labour market]. Budapest: MTA KRTK.

Bubalo Živković, M., Đurđev, B. S., Dragin, A. (2008):

The Ageing of Vojvodina’s Population between 1953 and 2002 with Reference to Middle Adulthood and

Ageing Index. Geographica Pannonica, 12(1), 39–

Çağlar, A. & Gereöffy, A. (2008). Ukrainian Migra-44.

tion to Hungary: A Fine Balance between Migra- tion Policies and Diaspora Politics. Journal of Im- migrant & Refugee Studies, 6(3), 326–343.

Danka B. (2010). Migráció a felsőoktatásban [Migra- tion in higher education]. Budapest: BÁH. http://

www.bmbah.hu/ujpdf/MIGRACIO_A_FEL- SOOKTATASBAN.pdf?PHPSESSID=5636863d8c1 6f7e2aa221f33543ef68f

Epare, C. (2008). A nemzet peremén. Külhoni magyar ösztöndíjasok a fővárosban [At the margin of the nation. Transborder Hungarian students in Buda-

pest]. In L. Szarka & E. Kötél (eds.), Határhelyzetek.

Külhoni magyar egyetemisták peregrinus stratégiái a 21. század elején (pp. 10-29). Budapest: Balassi In- tézet Márton Áron Szakkollégium.

Erdei, I. (2005). Hallgatói mobilitás a Kárpát-meden- cében [Student mobility in the Carpathian basin].

Educatio, 14(2), 334–359.

Faist, T. (2016). Cross-Border Migration and Social Inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 42(1), 323- Feischmidt, M. & Zakariás, I. (2010). Migráció és et-346.

nicitás. A mobilitás formái és politikái nemzeti és transznacionális térben [Migration and ethnici- ty. The forms and politics of mobility in national and transnational space] (pp. 152-169). In M. Feis- chmidt (ed.), Etnicitás. Különbségteremtő társada- lom. Budapest: Gondolat, MTA Kisebbségkutató Intézet.

Fercsik, R. (2008). Szülőföldről a hazába – és vis- sza? [From the homeland to the motherland – and back?] (pp. 124-138). In L. Szarka & E. Kötél (eds.), Határhelyzetek. Külhoni magyar egyetemisták pere- grinus stratégiái a 21. század elején. Budapest: Bal- assi Intézet Márton Áron Szakkollégium.

Gábrity Molnár, I. (2002). A fiatal értelmiségképzés lehetőségei [Educational possibilities of young in- tellectuals] (pp. 13-38). In I. Gábrity Molnár & Zs.

Mirnics (eds.), Holnaplátók. Szabadka: Magyarság- kutató Tudományos Társaság.

Gábrity Molnár, I. (2007). Vajdasági magyar diplomások karrierje, migrációja, felnőttoktatási igényei [Career, migration, and adult education needs of diploma-holding Hungarians in Vojvodi- na] (pp. 132-173). In K. Mandel & Zs. Csata (eds.), Karrierutak vagy parkolópályák? Friss diplomások karrierje, migrációja, felnőttoktatási igényei a Kár- pát-medencében. Budapest: MTA Etnikai-nemzeti Kisebbségkutató Intézet.

Gödri, I. (2004). Etnikai vagy gazdasági migráció?

Az erdélyi magyarok kivándorlását meghatározó tényezők az ezredfordulón [Ethnic or economic migration? Factors in the emigration of Transylva- nian Hungarians]. Erdélyi Társadalom, 2(1), 37-54.

Gödri I. (2005). A bevándorlók migrációs céljai, mo- tivációi és ezek makro- és mikrostrukturális hát- tere [Immigrants’ migratory objectives and mo- tivations and their macro- and microstructural background] (pp. 69-131). In I. Gödri & P. P. Tóth (eds.), Bevándorlás és beilleszkedés. Budapest: KSH Népességtudományi Kutatóintézet.

IDKM (2010): Migrációs szándék a vajdasági magyar egyetemisták körében [Migratory intentions of the Hungarian students of Vojvodina]. Zenta: Identitás Kisebbségkutató Műhely. http://www.idkm.org/ta- nulmanyok/Migracios_szandek1.pdf

Imre, A. (1993). Iskolák a határon. Határmenti tér- ségek és az oktatás [Schools at the border: Border zones and education]. Budapest: Oktatáskutató In- tézet.

Jordan, B. & Düvell, F. (2003). Migration: The Bounda- ries of Equality and Justice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kincses, B. & Nagy, G. (2019). A vajdasági magyar hallgatók iskolaválasztási attitűdjének vizsgálata a Szegedi Tudományegyetemen [Examination of the school choice attitude of Hungarian students from Vojvodina at the University of Szeged]. Területi Statisztika, 59(2), 219–240.

Korhecz, T. (2010). A kettős állampolgárságról [On dual citizenship]. Kisebbségkutatás, 19(1), 11-18.

Kováts, A. & Medjesi, A. (2005). Magyarajkú, nem- magyar állampolgárságú tanulók nevelésének, ok- tatásának helyzete a magyar közoktatásban [Ed- ucational situation of Hungarian students with non-Hungarian citizenship]. Budapest. http://www.

okm.gov.hu/upload/2007003/hatarontuli_mag- yarok_tanulmany_070320.pdf

Levitt, P. & Glick Schiller, N. (2004). Conceptualiz- ing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Per- spective on Society. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1002-1039.

Márkus, Z. (2014): Eljönni. Itt lenni. És visszamenni?

A határon túli magyar hallgatók a magyarországi munkaerőpiacon [Coming. Being here. And going back? Transborder Hungarian students in the Hun- garian labour market]. Educatio, 23(2), 312–319.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Greame, H., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of International Migration: A Review and Apprais- al. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–

Milovanović, Z. (2006): Starosna struktura 466.

stanovništva Vojvodine prema teritorijalnoj i na- cionalnoj pripadnosti [Age Structure of the Popu- lation of Vojvodina According to Territory and Na- tion]. Zbornik Matice srpske za drustvene nauke, 121. 305–312.

Molnár, C. (2008). Érvényesülés, karrierépítés – haz- atérés. Hallgatói döntéshelyzetek [Success, career – homecoming. Students’ decisions] (pp. 139-154). In L. Szarka & E. Kötél (eds.), Határhelyzetek. Külho- ni magyar egyetemisták peregrinus stratégiái a 21.

század elején. Budapest: Balassi Intézet Márton Áron Szakkollégium.

Palusek, E. & Trombitás, T. (2017). Vajdaság demográ- fiai és migrációs jellemzői [Demographic and mi- gration peculiarities of Vojvodina] (pp. 41-72). In T. Ördögh (ed.), Vajdaság társadalmi és gazdasági jellemzői. Szabadka: Vajdasági Magyar Doktoran- duszok és Kutatók Szervezete.

Pogonyi, S. (2015). Transborder Kin-minority as Sym- bolic Resource in Hungary. Journal on Ethnopoli- tics and Minority Issues in Europe, 14(3), 73–98.

Salt, J. (2001). Az európai migrációs térség [Migratory spaces of Europe]. Regio, 12(1), 174-212.

Stewart, M. (2003). The Hungarian Status Law: A New European Form of Transnational Politics? Diaspo- ra: A Journal of Transnational Studies, 12(1), 67-101.

Szentannai, Á. (2001). A Magyarországon tanult fiatalok karrierkövetése [Career paths of youth ed- ucated in Hungary]. Regio, 12(4), 113-131.

Szügyi É. & Takács Z. (2011). Menni vagy maradni? Es- élylatolgatás szerbiai és magyarországi diplomával a Vajdaságban [To go or to stay? Chances with Ser- bian and Hungarian university degree in Vojvodi- na] (pp. 283–300). In B. Páger (ed.), Évkönyv 2011.

Pécs: PTE Közgazdaságtudományi Kar Regionális Politika és Gazdaságtan Doktori Iskola.

Takács, Z. & Gábrity, E. (2014). Development of High- er Education Networking in Multiethnic Border Region of North Vojvodina (pp. 252-274). In M. Bu- fon, J. Minghi & A. Paasi (eds.), The New European Frontiers: Social and Spatial (Re)Integration Issues in Multicultural and Border Regions. Cambridge:

Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Takács, Z., Tátrai, P. & Erőss, Á. (2013). A Vajdaság- ból Magyarországra irányuló tanulmányi célú mi- gráció [Educational migration from Vojvodina to Hungary]. Tér és Társadalom, 27(2), 77-95.

Tátrai, P., Erőss, Á. & Kovály, K. (2017). Kin-state pol- itics stirred by a geopolitical conflict: Hungary’s growing activity in post-Euromaidan Transcar- pathia, Ukraine. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 66(3), 203–218.

Tilly, C. (1991). Transplanted Networks (pp. 79–95).

In V. Yans-McLaughlin (ed.), Immigration Recon- sidered: History, Sociology, and Politics. New York

& Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mirnics, Z. (2001). Hazától hazáig [From home to home] (pp. 163-204). In I. Gábrity Molnár & Z.

Mirnics (eds.), Fészekhagyó vajdaságiak. Szabadka:

Magyarságkutató Tudományos Társaság.

Tóth, P. P. (2003). Nemzetközi vándorlás – magyar sa- játosságok [International migration – Hungarian peculiarities]. Demográfia, 46(4), 332-341.

Waterbury, M. A. (2010). Between State and Nation.

Diaspora Politics and Kin-state Nationalism in Hungary. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.